Gianfranco Rosi and Charles Bowden on Murder in Mexico

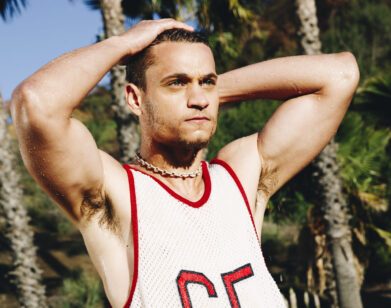

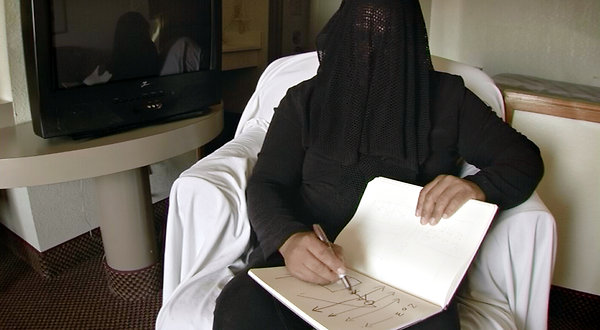

ABOVE: A STILL OF EL SICARIO FROM GIANFRANCO ROSI’S DOCUMENTARY, BASED ON CHARLES BOWDEN’S ARTICLE ON THE SUBJECT.

In a small, unremarkable ground-floor motel room in the middle of the desert sits a man wearing a black veil over his head. He has the body of a linebacker and in his thick hands holds a sketchbook and brown marker. His voice is unassuming. The black void of his face stares directly at the camera. The viewer soon learns is that this is the Sicario, a professional killer. What follows, in great detail, is his life: how and why he killed, why he left it behind, and the high-priced contract currently out on his life. The motel room, we later find out, was conveniently picked by the Sicario because it was the former stage for torture and murder.

El Sicario, Room 164, directed by Gianfranco Rosi, is inspired by the work of Charles Bowden, a journalist who has spent many years covering crime in Ciudad Juárez. He wrote about the Sicario for Harper’s in 2009. With Rosi and Bowden working together, the film is more than a companion piece to Bowden’s writing—its frankness and immediacy is more startling than any piece of writing can achieve. The interview below is condensed and combined from conversations with Bowden and Rosi, in which they discussed the film and Juárez at length.

CHARLES BOWDEN: You sit there, year after year, seeing these bodies, and you want to know where they’re coming from. Then you finally meet one of the workers. That was why I originally wanted to do the article. I wanted to get this guy on paper.

GIANFRANCO ROSI: I met Chuck a few years ago. I did another film, before this, in the States, called Below Sea Level. The film took place in the desert, in the Southern United States.

BOWDEN: He looked me up. He was driving across Nevada or Utah and heard me on NPR. About once a year, NPR loses its mind and interviews me.

ROSI: I called Chuck by phone and said, “You’re the person I want to meet.” He said, “Can you cook?” [laughs] From Los Angeles, I drove to Arizona with pasta, wine, lots of things, and ended up spending 10 days with him. We became friends. Then he came to Italy and helped me a lot with the film, which is a film that unfortunately didn’t come out in the United States. But it’s real. [laughs] Chuck helped me a lot in the editing. That was maybe ten years ago.

BOWDEN: We were having drinks in New Orleans and I showed Gianfranco the manuscript [of the article].

ROSI: I said, “Someone should make a film about that.” He said, “You should do it.” A few weeks later, he said he spoke to the guy and he’s willing to do the film under certain conditions. Chuck said, “If you accept his conditions, don’t fuck it up.” I had one week.

BOWDEN: The real thing is I knew Gianfranco, and I trusted him. I knew he had the skills, that was a given. I wouldn’t want to introduce anybody to the Sicario and they make the big scary Frankenstein film. I want the film where you have to meet this kind of person and learn. The real horror of the film, for viewers, if they’re intelligent, is that they end up liking him—to their horror, because they have to face the fact that he’s a human being.

ROSI: I went down there and I spent two days waiting for him. Then I shot one day, and then I spent another two days waiting for him. When he came back, I filmed the other angle, of the sketch book. He went through the whole book again explaining what happened. After that, I had to leave the room.

BOWDEN: I don’t think he ever intended to go as far as he went. He broke down two or three times during the filming. The reason some people think he’s an actor is because he eviscerated himself on camera. He didn’t intend to.

ROSI: If he’s an actor, then I want an Academy Award for Best Director! [laughs] I want to say, in Mexico, nobody for one second thought he was an actor. This is a film that, for the first time, tells the truth of what is going on down there.

BOWDEN: Are these the same people who think we didn’t land on the moon, that we did it on a sound stage in Oakland or something? [laughs]

ROSI: When I went back to Italy, I had to make sure what I did made sense. Then I realized I had nothing about the space. I went to spend another month in Juárez filming, with a journalist, all the locations. I was filming five to six murders a day with this journalist. This is another film, basically.

BOWDEN: There are a lot of edits in the film, and it isn’t because of stumbles; it was an embarrassment of riches. The Sicario is just totally lucid. At one point, we all sat there and said, “We could do Shoah.” [laughs]

ROSI: In the end, the film gives less information—like a Giacometti statue, how thin could it go before it breaks. It’s a portrait of a soul.

BOWDEN: I hate narrators—I don’t think writers belong in films, they belong in books. You have to give readers a person; a guide into hell. You don’t need that in the film, because you have the Sicario himself. I didn’t want any narrator [in the film] because I’m tired of viewers being protected. I’m tired of the narrator standing between the viewer and the thing itself to make it safe. I didn’t want any security for the people who see the film, nor is there any, based on the reactions I’ve seen.

ROSI: When I was in Denmark showing the film, there was something like 800 people in the theater. I never go see to screenings of my film—but I went inside for 15 minutes, and suddenly I felt the audience breathing like him. [makes heavy breathing noise] Like that. It’s a totally absurd fear—you’re bringing people in this room, not telling them what is going to happen in this room, and leaving them there. But that was what happened to me, so I wanted the audience to go through the same feeling as me. If people could feel what we were feeling in the room, the film could work.

BOWDEN: He’s also extremely coherent. I think [the reaction is due to] racism, in part. You’ve got a lower-class Mexican who never stumbles. He’s very well spoken. He’s also reflective. Even if people are as good as he is, most of them can’t say it.

ROSI: The film is pure witnessing. Beside the few tools I gave him as a director—the veil he wears, I transformed the room into a stage—it was a pure monologue. The tools allowed him to go inside himself.

BOWDEN: The veil had a consequence I certainly never saw coming. It was like the Sicario got into a confessional in church. In a very real sense, we weren’t there. He was there.

ROSI: I never asked him any questions, really. The only thing I asked him was to write everything down. I knew he went from this point to this point in his life. I always say, as a joke, that this is not a talking head film but a talking hands film. The hands were the only way of showing the truth. I couldn’t see his face, so the hands for me were the only thing. Somehow it works.

BOWDEN: Gianfranco directed this, but the Sicario at a certain level took over the movie.

ROSI: The Sicario saw the first cut of the film. I went back and showed it to him. After that, we were in contact a little bit—he was writing, things like that. All of a sudden, he left.

BOWDEN: He disappeared. I’ll tell you why. He’s a Christian; I’m a little shaky in religion. For him, it’s a missionary act, to get on record how he lived and why other young men from his background should never make the decision he made. Proceso is the most prestigious, influential magazine in Mexico; they were interviewing me because of Murder City, and I said, “You know, I have this little film.” I slipped them a copy, and they took a freeze frame and put it on the cover. That’s when he disappeared. I gave him some money I didn’t have, and that’s all I know.

EL SICARIO, ROOM 164 IS NOW PLAYING AT FILM FORUM IN NEW YORK.