director

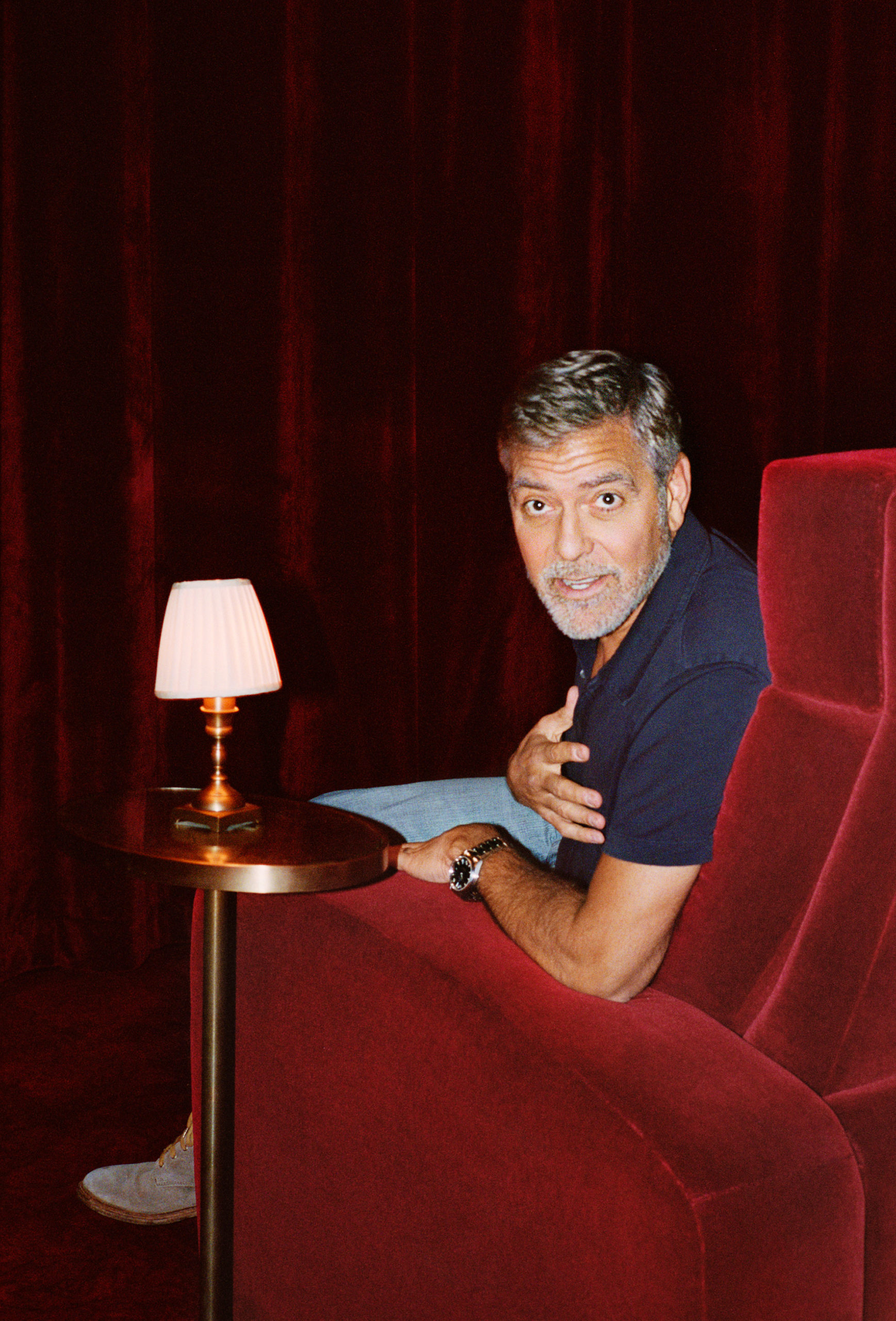

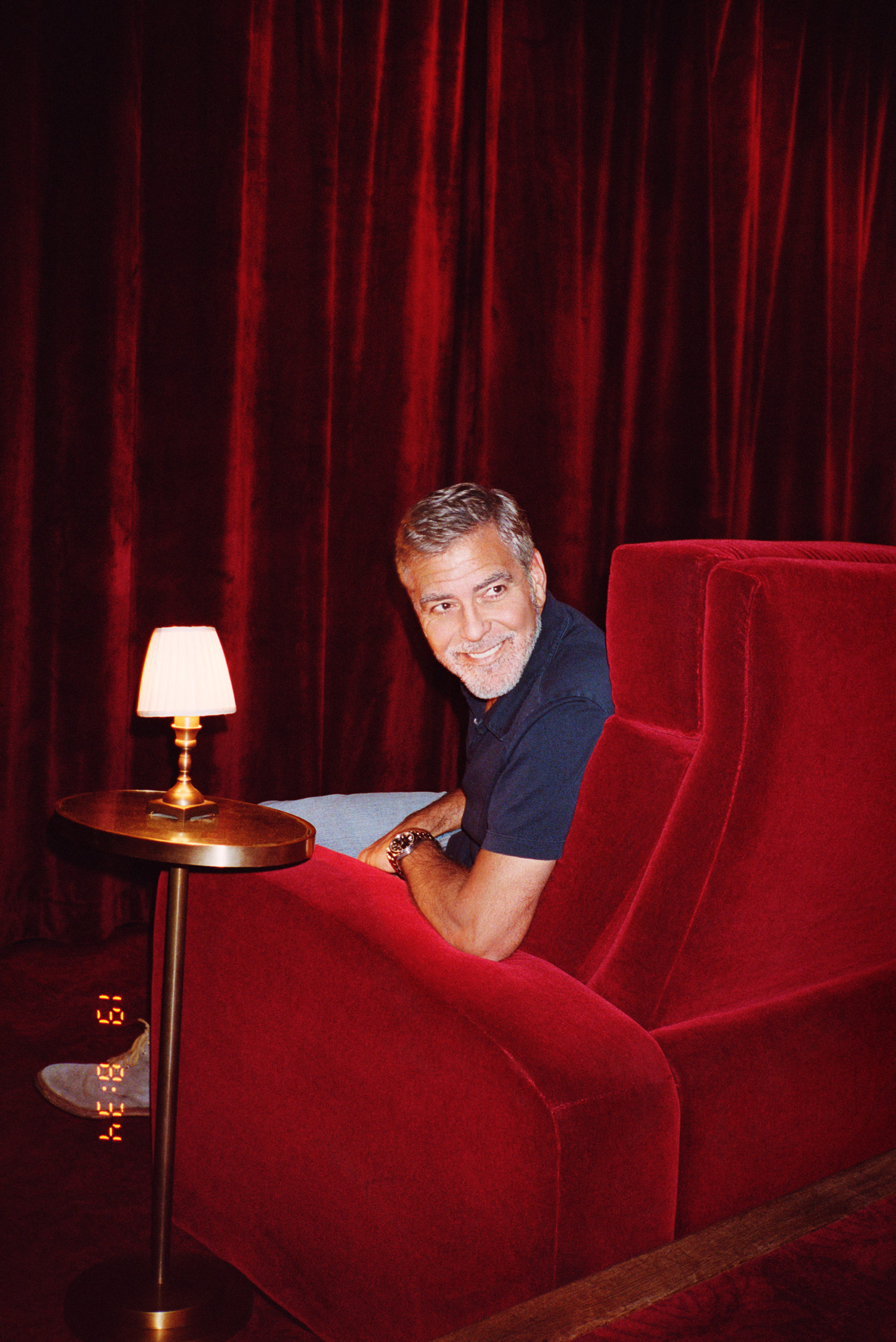

George Clooney and Matt Damon Are Still Trying to Figure It Out

George Clooney has defined and redefined charisma so many times in his 40-plus–year career that his name ought to be synonymous with it. From an early guest role as a fresh-faced handyman on The Facts of Life to his collection of Oscar gold as both an actor and producer, and with multiple identities as a humanitarian, entertainer, and activist, the 60-year-old icon has proven that masculinity isn’t always toxic. So who better to direct an adaptation of The Tender Bar, J.R. Moehringer’s best-selling ode to the “male sciences,” in which an all-in Ben Affleck shows a wide-eyed Tye Sheridan the ropes of being a man in the 1980s? And who better to talk through the project than his old pal Matt Damon, who is no stranger to working with Affleck and the crazy business of making movies? As can be seen in the following conversation, the answer is no one. — JESSE DORRIS.

———

MATT DAMON: Hey, Georgie.

GEORGE CLOONEY: Hey, Matty boy. Where are you?

DAMON: I’m in New York. Where are you?

CLOONEY: I’m in London. Day after tomorrow, I go to Australia. I’m doing a movie with Julia [Roberts].

DAMON: I heard all about it when I was down there. Everyone was excited for you to come.

CLOONEY: It’s going to be fun. I haven’t done a romantic comedy since, I guess Out of Sight, and that was 1998. This one’s like Dirty Rotten Scoundrels. Julia and I just fuck each other over all the time. That sounds like fun to me.

DAMON: Are you shooting on the Gold Coast? Or Sydney?

CLOONEY: We’re going to start at the Whitsunday Islands and then we’re in Brisbane. All doubling for Bali.

DAMON: How long are you there for?

CLOONEY: Until the end of January. And then I come back to London and we’re shooting The Boys in the Boat right away. So, how are you doing? Are you okay?

DAMON: Yeah, I think so.

CLOONEY: Listen brother, someday you and I will sit down and figure this industry out.

DAMON: Not anytime soon. Twenty years ago we talked about how Napster was going to come for movies. But one thing I didn’t anticipate was the way these things would change the content, because suddenly the movies that were our bread and butter don’t have a DVD coming behind them that was a revenue stream you could depend on.

CLOONEY: It’s been happening for a while. Part of the reason why [Steven] Soderbergh and I pushed to start Warner Independent was because we needed some place to go where we could make movies that we liked to do, because honestly, if you go to big Warner Bros. and say, “I’m going to shoot Good Night, and Good Luck for $7 million,” they can’t really conceive of doing a film for that amount and then spending $40 million on the marketing campaign. So you really needed these other places to go. The streamers have supplied that in a way. Our major responsibility is to make sure there’s a good solid theatrical window that comes along with it. That keeps the theaters in business, whether they want to do business with films like that or not. That’s always a complication, because when we did this last film with Ben, that’s not a big wide-release film. It wasn’t designed to be. The budget on it was really small. Ben took a big cut. We hired Ben over you because he was much cheaper.

DAMON: [Laughs] I was wondering about that, or if it was that you were upset with my work in Suburbicon.

CLOONEY: We actually asked your agent, who is the same as Ben’s. We said, “How about Matt?” And he goes, “How about I give you Ben and you save some bucks?” I thought, “Well, that’s a nice offer right there.”

DAMON: What was it like working with him? He obviously loved the script that [William] Monahan wrote, but he said that he got some of the best direction he’s had in his career from you. And I was thinking, “Well, where the fuck did that come from?” I mean, I’ve done three movies with you. [Laughs]

CLOONEY: “Worst director I’ve ever worked with!” [Laughs] When you guys came out of Good Will Hunting, there was that moment that happens when something hits, where suddenly you get that stardust thrown on you and they go, “Okay, you’re going to get your opportunity.” You and Ben went in a little bit different directions. Ben did some Armageddon kind of movies so he wasn’t given enough credit for his talent as an actor, and wasn’t given the kind of roles that he was capable of doing. He had a couple, but not many. And then he directed his way out of that problem and changed his career in a big way. I sent The Tender Bar script to him and said, “What do you think?” He wrote me a three-page email about everything he knew about this character. I think there are parts of his father that he related to in it. It just felt like Ben really wanted to do this and was ready to do it. And he really showed up—the first guy on the set; he knew everybody’s lines. He’s a consummate pro. So, directing him really wasn’t the best direction he’s ever gotten, meaning I didn’t say anything to him, which is maybe what he wanted all along .

DAMON: You’re being humble. He said that you didn’t say a lot, but you always said the right thing. I remember seeing Sean Penn on Inside the Actors Studio where they asked him what he didn’t like in a director, and he said, “Too much chatter,” which is really relatable for all of us, because there are only so many notes that you can take and so many adjustments you can make.

CLOONEY: The very first job I did with the Coen brothers was O Brother, Where Art Thou? I was nervous, man. It was the Coen brothers and they were already gods. And I had this great part, this idiot named Everett. On the first day, the first scene was the one where John Goodman hits me in the head with a branch and knocks corn out of my mouth. I did the scene in one take, and I played Everett like an idiot because he’s an idiot. Joel [Coen] came over and went, “Just remember you’re the smartest guy in the room in every room you walk into.” That’s kind of the last thing he said to me for the whole movie. And I was like, “Oh fuck, of course. You’re right.” It was freeing. Oftentimes, directors don’t give actors notes like that because they are thinking about the results and not the process. But Ben understood his character from the minute he got in.

DAMON: Backing up a little, I haven’t heard anything about how you got involved with the movie. Did you get the material and commission Monahan? Or did he write it and you read it?

CLOONEY: Grant [Heslov, Clooney’s producing partner] and I chased the book when it first came out and we lost out to Scott Rudin. Then last year, when we had just finished doing The Midnight Sky, which is a pretty depressing film, Amazon sent it to me and said, “We’re going to do this on a budget if you want to do it.” I read it, and it’s a gentle film. I feel like my fists and jaw have been clenched for six years. And everybody’s so angry. So the ability to do a film that is just about kindness and love and support, I sort of needed it, and when I read it, I thought, “Maybe people are up for that, too.”

DAMON: There are many ways in which it is nothing like your life, but did you have your own “Uncle Charlie”?

CLOONEY: I had an Uncle George. I was named after him. He was my dad’s uncle, so he was actually my great uncle, but he was only a couple of years older than my dad. In the summers when I was around the same age as J.R. 5 at the same time the movie is set, I would work at River Downs racetrack in Cincinnati, and I lived above a bar exactly like the one in the movie with my Uncle George. So all of that was really familiar to me.

DAMON: That’s cool. I didn’t know that about your uncle, but it’s interesting, because you’re like that for a lot of people; certainly for actors who are younger than you. A lot of people go to you for advice.

CLOONEY: Listen, my Uncle George was in many ways a cautionary tale. He was a B-17 bomber pilot hero in World War II. He dated Miss America. He was my Aunt Rosemary’s band manager. I mean, he was the shit, and he was also a terrible alcoholic. He was one of the funniest men I ever knew, but when he was drunk, which was often, he was terrible. He was vicious and mean and had none of the qualities of the Uncle Charlie character. But you’re a writer, and you know that when you have fully fleshed-out characters, everything about telling a story gets easier. The Tender Bar is not a story where too much happens—that’s sort of the charm of it, that it’s just about people making sure that somebody gets out. And it’s like The Wizard of Oz in the sense that it’s about a young man who keeps looking for something that he had all along—searching for a father when he had Uncle Charlie, who was infinitely better than the father that he thought he wanted. I think we all have some of that in us, and learn that kind of lesson. I liked that it was just a piece of life. And we filled it with all these great people. I called up Grant, and I said, “Who I would like to get to play Grandpa is Christopher Lloyd.” Because for my whole life, I’ve been doing Christopher Lloyd impressions. I love the guy so much, and he’s finally the age he’s been playing for 40 years. I was shocked he said yes to the role, because it wasn’t a huge part and he was overqualified for it. But it’s a fun part, and he did it beautifully. And Briana [Middleton], who plays J.R.’s girlfriend Sidney, this is her first acting job on the big screen and she’s spectacular.

DAMON: Where did you find her?

CLOONEY: She read. We read a lot of actresses, but we needed someone who was able to do a lot of rotten things along the way that you still didn’t completely hate. And it’s hard to act that. But she has a really lovely quality. Then Tye [Sheridan] came in and read for J.R., and he gave a really wonderful performance. And he’s a Southern boy from Elkhart, Texas, and he talks with a drawl, so he had to work harder because it’s an accent.

DAMON: He’s terrific. I wouldn’t have known that.

CLOONEY: Yeah, he’s really good. You’ve got to root for J.R. If people don’t root for him, you lose. It was that same vibe when we did Catch-22 with Chris Abbott playing Yossarian. If you root for Chris as Yossarian, then Catch will work. And he was spectacular in the role. I keep wanting Chris to really break.

DAMON: Me, too. That guy popped off the screen.

CLOONEY: I think he’s going to. He’s in Budapest working right now, and he’s also a really good guy. So I do think that’s going to happen. And again, it’s kind of that thing with Ben where there’s a time and place when an actor’s right. I did, what? Seven TV series and 13 pilots before ER? I was beat up on all sides by the time ER came around.

DAMON: I remember Ben met you at a backyard barbecue in 1993 or ’92. And he was like, “I met the nicest guy. He’s been on ten TV shows.”

CLOONEY: “He can’t hold a job, that guy.” [Laughs] I remember when you came over, I’d just put a screening room in my house. What year do you think that was?

DAMON: That would’ve been 1999, I think.

CLOONEY: Yeah, because you were about to do that golf movie [The Legend of Bagger Vance], right?

DAMON: That’s exactly right. I was about to go do it, and I’d never played golf. And I remember, you modeled a swing for me. You were like, “It’s easy. You’ve just got to get a little rotation in your hips.” And I remember thinking, “God, I wish I could do that. I’ll get away with this movie if I can just do that.” That was when you told me that thing that Paul Newman had said to you, “Don’t let them keep you inside.”

CLOONEY: Yeah. It was only a couple years earlier that I saw Paul Newman on the backlot of Warner Bros. He was sitting in a golf cart and I walked over like, “Hey man.” And he’s like, “Hey, what’s happening?” And I was like, “Not much.” And he didn’t know who I was, really. But it was well into ER and I’d done a few movies, and I was kind of the mayor of Warner Bros. because I’d been in every stage for years and years, before ER, even. And so people kept driving by going, “Georgie!” and waving. So Paul slowly figured it out, and he goes, “Out of Sight, right?” And I was like, “Yeah.” And then he just says, “Don’t let them keep you inside.” It was a funny thing, because I was kind of hiding then, because I hadn’t been in that position. That’s why I said it to you.

DAMON: When you said it to me I was in the exact same place. It’s a real mindfuck when your life gets tipped over like that. And it certainly led me to want to hide in a crouch.

CLOONEY: It’s a bug light, right? You go flying right at it because you’re desperately trying to work, and to achieve something that puts you in a position where you can continually work, and then when you get there, you get zapped. You go, “This is a lot. I’ve lost all privacy.” I also remember us having a conversation about how long careers last.

DAMON: Yes, that was when we shot Ocean’s 11 in Chicago in early 2001, and we were at a bar. We had that discussion about how a decade in this business was almost unattainable, about that really being the goal. Because I think we were talking about the big movie stars in 1991, and as we walked through them, we were like, “Oh man, that person’s not here anymore.”

CLOONEY: I saw some website where they showed the careers of the biggest stars of all time, like Cary Grant. And it was all, like, 20 years. It’s not as long as you think. And you’re like, “Holy shit. It’s hard to keep working.” Some of the reason why you started writing was because you were trying to write yourself a part, right?

DAMON: Yeah.

CLOONEY: And for me it was that I didn’t want to worry about what some casting director thought of me when I was 50 or 60.

DAMON: And now we are. [Laughs]

CLOONEY: So here’s a question. Should we do another Ocean’s film? [Laughs] It’s all I get asked. I think we should. We’d have to do it in style, right?

DAMON: Yeah, exactly.

CLOONEY: We’re all wetting ourselves, holding canes and things.

DAMON: [Laughs] With this business there are obviously all of these sea changes that we can’t control, but given that you are a writer, a director, a producer, and an actor, and you can create your own stuff, what’s coming in the next 10, 20 years?

CLOONEY: I had a conversation with Amal [Clooney] the day after I turned 60. I had just done the body scans, checked for cysts and polyps, had a colonoscopy, blood tests, and everything was fine, knock on wood. I said, “Okay, so I’m 60 and I feel really good. I can still play basketball. I can still run around. But in 20 years, I’m 80. And I don’t care how good you eat, and how well you take care of yourself, 80 is a real number. So we have to make sure that we properly extract everything out of the next 20 years.” And that means we have to work, because if either of us stopped working we would actually go crazy. But we have to do it with the idea that we’re not rushing towards some finish line. My goal is to pay a little more attention to life in general, because I think actors, directors, writers, and all of it, we’re always in such a desperate rush not to step off the gas, and the panic sort of sets in that if you do, then that’s it. I’m still getting nice offers to work, so as long as they let me play in the sandbox, I’ll play in the sandbox, but I don’t have to fill it with all the toys anymore. That’s been the exciting and realistic part of aging. Are you still on the mad dash?

DAMON: God, no. I felt really good about these last two movies that I worked on, and they got worked like the ’85 Pats, but there’s nothing you can do about that. But I spent those years the way I did as a younger guy because I loved it so much. I loved living out of a duffle bag. I just took jobs, and I learned a lot that way. We always talk about it as a trade, and the best way to become a carpenter is to just keep building houses.

CLOONEY: It’s funny—when you get successful, they give you a trailer. I’m from Kentucky. Trailers are not a status symbol for us. But when we did Ocean’s, none of us were ever in our trailer because you could sit on set and listen to Carl Reiner, Elliott Gould, and Bernie Mac. I’m still very excited about going to work every day.

DAMON: And something that you do as a director, and that Steven does, and that a lot of the people we’ve worked with do, is create so much momentum around the camera that you don’t want to be anywhere else.

CLOONEY: Well Soderbergh, who was sort of my teacher in how to make films and tell stories, said, “Always shoot with a point of view.” And part of shooting with a point of view is that you’re only covering the shots that you know you’re going to use. So you’re not going into an editing room four months later and trying to come up with a story. You’ve picked your story, and you’ve put your pencil down, and you can hand in your homework.

DAMON: What would you do if you walked onto a set right now, and after one day you realized that it was just master, two-shot, over, over, single, single? Tons of takes. I don’t think I’d have the patience anymore to do it. That’s not directing. Do you think you’d ever even find yourself in that situation?

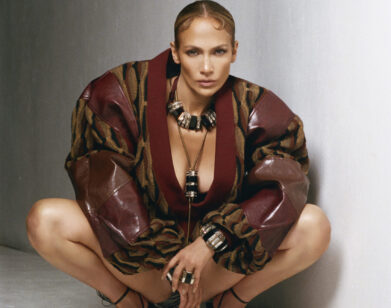

CLOONEY: I would hope not. The best thing you can do as a director is to make the actors feel safe and comfortable, and you’ll see some really interesting stuff happening. You can do 55 takes and maybe you’ll find what you want, but to me, that’s not doing your job. That’s just wearing people down. As an actor, I would despise doing a film like that. And listen, when we were doing Out of Sight with Soderbergh, and we did that scene with Jennifer [Lopez] in the back of the trunk, the plan was to do it in one take, but it took us all day, and we didn’t get it. It was like 40 takes. But that was an attempt to do something really big.

DAMON: What I love about Steven is that he’s so mercenary that even after all of that capital spent on getting it in one, you guys still cut it.

CLOONEY: Well, we had to go back and reshoot. He came to me and said, “We’ve got to go back in the scene.” I said, “You’ve got to be fucking kidding me. After all that?” He was like, “Yeah, we have to.” The first thing I directed was Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, and after I finished it, it was about 2 hours and 35 minutes, so I knew I was going to have to cut something. I had this really complex shot that I was very proud of, and the first person I screened the movie for was Soderbergh. He watched it, and goes, “You’re going to cut that scene.” I was like, “You’re out of your mind. It’s the best shot in the whole thing.” And he goes, “You’re going to cut it,” and I go, “No, I’m not.” Then, two months later, I was sitting in the editing room, and I was like, “Fuck, he’s right.”

DAMON: That’s what Walter Murch always called “preserving your virginity.” That’s why he doesn’t go to the set—he doesn’t want to know how long a shot took, because then you invest in it. You have to be able to look at it totally apart from the set.

CLOONEY: Oh, that’s brilliant.

DAMON: Steven always talks about “movie, scene, moment.” That’s your hierarchy: the movie, then the scene, then the moment. And actors, of course, do it in reverse, like, “Oh, that moment.” And it’s like, “No, we’re chucking it to make the scene better.” Or, “We’re chucking that scene to make the movie better.”

CLOONEY: Part of the reason why Soderbergh and I clicked was because on Out of Sight, I would give him notes where I would say, “You should cut me out of that scene,” because I was watching it as a storyteller. But I remember doing a scene in O Brother where they’re going to hang us, and we get down on our knees crying, and I’ve got real tears pouring down my face. And I’m feeling like, “Man, I’m kicking some ass right here. This is good shit.” Then, when I saw the cut, they didn’t use that take. They used the goofy one. I was like, “What the fuck?” And they were like, “Yeah, it didn’t really make sense.” The thing is, actors try to cry. People try not to cry. So just seeing somebody trying to regain their composure afterwards is much more interesting. But it’s hard to tell actors that. I was in an acting class for ten years trying to cry, pulling nose hairs, anything I could do.

DAMON: [Laughs] That’s right.

CLOONEY: What else is going on? What’s your life going to be?

DAMON: I’m going to figure out if I’m going to write something else, or what the heck I’m going to do. I’m just getting everybody settled in New York and hanging out.

CLOONEY: After Australia I’m going to be in London shooting for a while, and then Italy. So you should come to Italy.

DAMON: Next summer?

CLOONEY: Yeah.

DAMON: Everybody reading this interview is invited.

CLOONEY: Everyone can come. I’ll pour prosecco for everybody. That’s kind of my real job.

———

Production: Siobahn Devlin at Devlin Webber London

Photography Assistant: Victor De Dalleux and Jori Komulainen