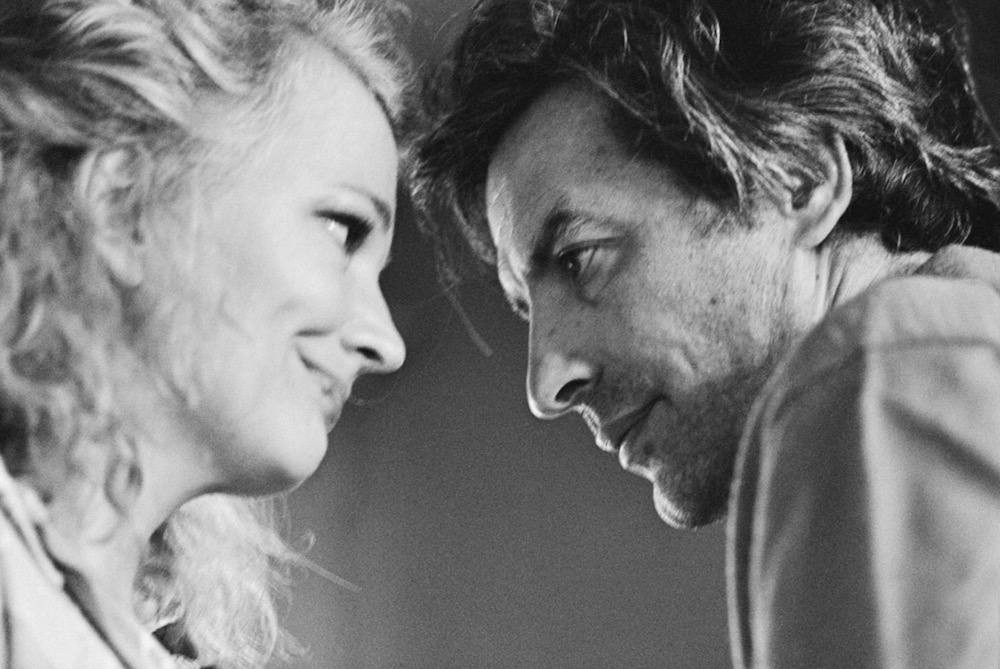

Gena Rowlands

“Wonderful” is a frequent descriptor in Gena Rowland’s vocabulary. She uses it to detail her early days as a stage actress for hire in New York, in the 1950s; writers like Paddy Chayefksy, the scribe of the play Middle of the Night, her breakout role; and the work of her late husband, John Cassavetes, who directed her in seven films, nearly all of which, like the devastating tale of an unraveling marriage Faces [1968] and the raw live wire of a familial drama Love Streams [1984], not just upended, but exploded, the paradigm of American filmmaking.

But beneath Rowland’s fine-boned patrician features and placid exterior is one of the most powerful, emotionally adept performers alive. Now 86, the Wisconsin native has built, from the heart outwards, psychologically nuanced and fully fleshed-out women on the fringe—like the functioning alcoholic stage actress about to give the performance of her life in Opening Night (1977), the unstable housewife Mabel Longhetti in A Woman Under the Influence (1974), and the tough-as-nails mob moll in Gloria (1980).

As a couple, Rowland and Cassavetes’ personal and artistic lives fed each other; Cassavetes routinely mortgaged their house in the Hollywood Hills to scrape up money to self-finance his films outside of Hollywood, and family and friends often joined his casts. Cassavetes even edited Shadows, his 1959 film, in the couple’s garage. On the process of their working relationship, Rowlands is quite cavalier. “He did his thing and I did whatever I thought,” she explains.

Starting this Friday, Metrograph will begin their series “Cassavetes/Rowlands,” a retrospective of the indie-before-there-were-indies power couple and collaborators’ indelible work. Interview recently spoke with Rowlands by phone while she was at home in Los Angeles.

COLLEEN KELSEY: Did you ever consider being anything other than an actress?

GENA ROWLANDS: Never in my life have I ever even thought about anything else.

KELSEY: Was there anyone you particularly admired when you were growing up? I know you’ve said Bette Davis.

ROWLANDS: I loved Bette Davis when I was little and when I was big and when I got old. [laughs] I just loved her and the fact that I had a chance to work with her [on the 1979 TV movie Strangers: The Story of a Mother and Daughter] was momentous. We had such a good time. She had very strong opinions and was not afraid to express them. She wasn’t afraid of anything that I ever saw. And she was so funny. She’s just funny and she was laughing all the time.

KELSEY: What did your parents think about you leaving college and moving to New York to become an actress?

ROWLANDS: I think I have the only parents in the world who would not have said something against that. When I went to them I was at the University of Wisconsin, and I just couldn’t wait anymore to go be an actress. I’d wanted to be one all my life. So I went home and I told my mom that I wanted to quit and be an actress and she said, “Huh, that sounds fascinating. It’s wonderful!” [laughs] And I told my father and he literally said, “I don’t care if you want to be an elephant trainer if it makes you happy.” That is how strictly I was brought up.

KELSEY: What was it like coming to New York at that time?

ROWLANDS: Wonderful. I think that I was lucky to have that period of time because everything was so exciting and new. I went to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, which was in Carnegie Hall, which itself was exciting—just to walk into it. It’s, I believe, on Madison Avenue now, I’m not sure. It was a period when live TV was just starting and getting popular and they took it seriously too. Not so much like TV now. They did Hemingway and Faulkner—and they’re all wonderful artists and it just was very creative at that time. Theater, too. Paddy Chayefksy was writing and it was a time where everybody was happy to be there.

KELSEY: You met your husband, John, at the Academy.

ROWLANDS: That’s right. He was a year ahead of me but we met there. What you do when you are at a school for drama, you do a play as opposed to a final. Anyone who wanted to come could just come. So he came, and I can’t remember the name of the play, of course, it was a long time ago. He came backstage afterwards and introduced himself and we talked a bit, and then went for a little coffee at the Russian Tea Room next door. It just…started.

KELSEY: Was John thinking about directing films when you first got together?

ROWLANDS: No. He was just being an actor. A very successful actor, especially in live TV. He did many wonderful performances. And then what happened was I got a part opposite Edward G. Robinson in a play called Middle of The Night, which Paddy Cheyafsky had written. It played for a long time because everybody just loved Edward G. Robinson, everybody in New York wanted to see it. John and I were married at the time and put into a position where I was working very long evening hours and he was working in the daytime and so there was a lot of spare time.

Because he was so terrific in live TV, a lot of his friends had not been able to participate in that yet and so they asked if he would gather with them at night when I was at the play and tell them what live TV was like, what you had to adjust to because it was its own medium—it had many things you had to be aware of. So he was happy to do that, and they had quite a good group of people. He was there at night while I was working. After they discussed as much live TV as they felt they needed to, they started improvising scenes just for the fun of it and one of those scenes everybody got very interested in and it turned into Shadows [1959]. That movie was entirely improvised. So many people mistakenly think that the rest of his pictures and the ones we did were improvised, which isn’t true. He wrote all the rest of them.

KELSEY: At that time your plan was to be a stage actress. What was the transition to doing movies with John?

ROWLANDS: When I was in Middle of The Night, MGM came and offered me a contract and I said that when I got out of the play, I’d like to try it. I didn’t know anything about making movies but I was certainly finding it interesting. So that’s what happened. We went…18 months, was it? By that time, John had shot a great deal of Shadows and I had to go fulfill my contract in California, so he and all the rest of the Shadows cast came out to California and they finished it off and he cut it. He turned the garage into an editing room and he was by then a director of Shadows. That’s the only thing he’d directed. But, he loved it. And so after that he acted and directed. And it worked out very nicely. And he wrote, obviously.

KELSEY: So what was your collaboration process like, as director and actress? When he was working on a script or a movie would he have an idea and bring it to you to talk about? Or would it be totally finished?

ROWLANDS: You would think that would be the case, but he didn’t like to talk about a part that I was going to play. And he didn’t like to talk about a play that he was writing. So it was very spontaneous for both of us. John loved actors. He gave them a lot of freedom. So if something came up that a certain actor just felt at the moment and said—that kind of improvisation he would accept. He gave very little direction. It was more freedom than I think most people get when they’re starting out—or even when they’re not starting out. He did his thing and I did whatever I thought. Of course I would change anything if he said so—it’s his script. But he was very easy about that.

KELSEY: John originally wrote A Woman Under the Influence as a play.

ROWLANDS: Yes. He wrote it as a play. He said, “Hey, I wrote you a play.” And I said, “Great, let’s read it.” I read it and I said, “John, I couldn’t do this every night and twice on Wednesday and Saturday. I wouldn’t be able to last two weeks. I’d die.” It was a very hard play to do every night. And he said, “Don’t worry. Don’t even think about it, you’re right. I hadn’t thought of that.” He said, “Just forget it.”

Then in about two weeks he said, “Okay. I solved the problem. I wrote a different play for you.” He said, “So you won’t have to carry all of it every night. I used the same characters but I enlarged different parts of the scenes.” He changed it generally to make it humanly possible. And I said, “Oh, that’s a miracle, let me see it.” And I read it and I said, “Listen, you must know a lot of strong actresses!” [laughs] I said, “I still wouldn’t be able to do it. This is really hard.” She has a nervous breakdown—there’s a lot of things that are hard emotionally to do. So he said, “Okay. I’m going to write it as a picture.” I said, “I think I can get through it once.” [laughs] “But I’m not making any guarantees.” He thought that was funny and then he wrote it thinking like an actor too instead of just a writer. I think he took that into consideration. And it is, of course, much easier to do a film when you’re doing an extremely emotional part than it is doing it onstage over and over especially.

KELSEY: Do you consider that to be your most challenging role? Mabel?

ROWLANDS: Well, yes, it was my favorite. I loved doing that. And it was challenging.

KELSEY: Since John gave you so much freedom to do what you liked as a character, how would you go about finding them? Was it something that was instinctual for you, from the script?

ROWLANDS: I read the script, you know, 50 times. And I thought about it. And then I did it. [laughs]

METROGRAPH’S SERIES CASSAVETES/ROWLANDS BEGINS THIS FRIDAY, JULY 15, WITH A SCREENING OF OPENING NIGHT. GENA ROWLANDS WILL BE PRESENT FOR A Q&A FOLLOWING THE FILM, AND AT SELECT SCREENINGS THROUGHOUT THE SERIES. FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT THE METROGRAPH WEBSITE.