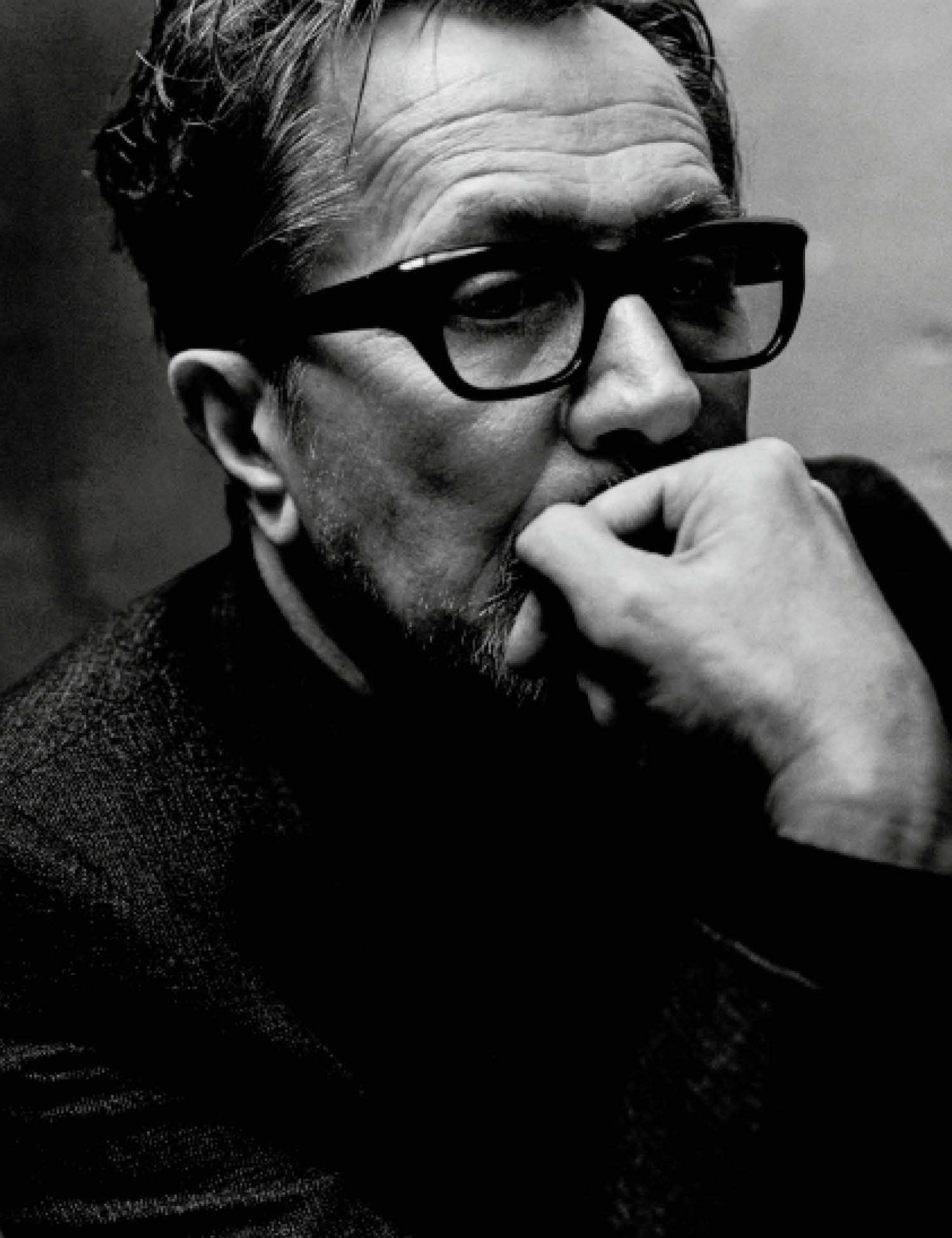

Gary Oldman

Few actors can do what Gary Oldman does. From Lee Harvey Oswald to Dracula—with a whole cadre of murderers, terrorists, and corrupt lawmen in between—the 59-year-old Brit has made a career out of disappearing into complex characters, not only mastering the way they look, move, and speak, but somehow also capturing their essence.

Oldman grew up in London, and after studying theater in college, spent his twenties treading the boards on the West End. He was introduced to the wider world in 1986, in his first lead role in a film, as the punk icon Sid Vicious in Sid & Nancy. He then transitioned from indie fare to big-budget movies, such as Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991); Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992); and Luc Besson’s The Professional (1994) and The Fifth Element (1997). In the 2000s, he debuted recurring roles in two major franchises: Sirius Black in the Harry Potter series and Jim Gordon in Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy. And in 2011, he beat his personal best with his Oscar-nominated portrayal of intelligence official George Smiley in the stylish Cold War–era thriller Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

This month, Oldman looks poised to take home his first Academy Award for his jaw-dropping performance as Winston Churchill in Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, a biopic about the British prime minister’s early days in office. Oldman has once again undergone a stunning physical transformation—over the course of filming, he spent 200 hours in the makeup chair—and yet despite the historical accuracy, there’s something inherently modern about a film whose protagonist stands against the tide of hatred and tyranny. As Oldman discusses with his friend and fellow WWII buff Jack White, it’s vital that we study the past to avoid, if at all possible, repeating it.

GARY OLDMAN: Jack, how are you?

JACK WHITE: I’m good. If it’s all the same to you, I’m going to be speaking as Winston Churchill for the rest of the interview.

OLDMAN: [laughs] Okay.

WHITE: [As Churchill] This is not the beginning of the interview, but it may be the end of the beginning.

OLDMAN: That’s fantastic. That isn’t in the film, but you’ve obviously done your research.

WHITE: How are you, sir? I haven’t talked to you in a minute.

OLDMAN: I’m doing well. I’m busy with things. I’m being creative, which is always good. What about you?

WHITE: I’ve been recording in New York, Los Angeles, and Nashville. I’ve never recorded in New York or L.A. before. I tried to go to some new places and meet musicians I’ve never met before, and see if I could get to a new place. I’m getting somewhere. I’ll send you something. It’s good gardening music or roofing music or, you know, back-alley stabbing music. [Oldman laughs] I’m trying to think of some good activities that people haven’t written songs for yet. What is good is this Winston Churchill performance. I had to keep staring at your eyes to see if it was really you. You’ve always been my favorite actor, and I’m not just saying that. The only date I went on in high school was to see Dracula. I used to get in big coffeehouse debates about your acting. I would say, “Every single time you see Gary Oldman, he is completely transformed into someone you can’t even recognize.”

OLDMAN: I think what it comes down to is that acting is an antidote to self-hatred. [both laugh]

WHITE: I’m going to write that down. I’m going to start acting some more now.

OLDMAN: I think it was my way out, a sort of avenue of escape. The fun of it was getting away from myself and stepping into the characteristics and the behavior of someone else. It stems from that thing of not necessarily being that comfortable in your own skin. But the challenge of playing someone like Winston Churchill is that there’s more footage of him than you might believe, and there’s certainly enough to read about. Next to Washington, I think he has the most biographies about him. And then there’s his own writing, which is something like 50 books.

WHITE: Churchill wrote 50 books?

OLDMAN: I haven’t read all of them, but I’m told every one of them is worth reading. He changed political parties twice. He fought with distinction in four wars, he served in politics, I think, for over 50 years, and he held almost every political office.

WHITE: This is Donald Trump you’re talking about? [Oldman laughs] No, it’s safe to say we don’t have leaders like that anymore.

OLDMAN: He defended the British constitution, won the Nobel Prize for Literature, painted 500 paintings, and exhibited at the Royal Academy. I mean, if you could find someone else who has done that …

WHITE: What is the general feeling about Churchill in Britain nowadays? Is he a controversial figure? Is he highly revered?

OLDMAN: I think he’s both. There’s a lot of rather radical, revisionist history that goes on with Churchill. He’s often misquoted or half-quoted. So it really depends on where you get your information. Not only was the cost of the First World War enormous in terms of lives, but it was also financially crippling to Europe. And then, of course, shortly thereafter, you had the economic crash, which was just devastating. People thought that the First World War was the war to end all wars. After that, it was peace at any price. While Churchill was researching a biography of his ancestor John Churchill, who was the Duke of Marlborough and a great general, he went to Germany in 1932 and saw firsthand what was happening there. They were re-arming. He raised the alarm in Britain, and that was very out of step with the atmosphere of pacifism.

WHITE: It’s also people not following history—if you horribly shame the loser of a war, you will fight them again.

OLDMAN: And sadly, we did. In Churchill’s research while writing this biography, he could see that there were certain repeating patterns. So he was coming out of years of thinking about war, studying war. He was equipped. It was like a muscle that he was exercising while Chamberlain was waving this piece of paper around, saying, “Peace in our time.” Churchill was considered a warmonger. I think that’s why he’s revered and hated.

WHITE: Churchill was the perfect person at the perfect time. What do you think of impressionists? When I see a comedian or an actor trying to do impressions of people, I sometimes wonder where the line is between someone who can do a very good impression and someone who is doing a very good job at acting and immersing themselves in a role. There must be some line when you were acting as Churchill. How do you know if you’re crossing the line into impression?

OLDMAN: I have a relatively good ear and can do a few impressions of people. I don’t study them, but I think what happens with an impressionist is that they’re looking at one particular source.

WHITE: Like, if they were to do the president, they would take one little thing he said and exaggerate it and make into a catch phrase.

OLDMAN: Yes, or a particular physical mannerism or something. But they’re only focused on that one thought. Impressionists have to paint with a very broad stroke because you’ve got to see it within a couple of seconds. You go, “That’s a really funny Robert De Niro.” As an actor, though, you look at different aspects of a character. I try to completely surround myself with the assignment. It’s like being in a big cloud and then some of it rains through—for instance, looking at not only Churchill’s way of walking and mannerisms and the way he sounds, but also looking into the psychology.

WHITE: You worked with Dennis Hopper in Chattahoochee [1990]—I watched him recently in Cool Hand Luke [1967]. He has a small part where he acts like he’s crazy. I didn’t meet him so maybe you can school me on this, but it seems to me that his real-life persona was like the characters he played. Like, if you met him at a bar, you’d say, “Wow, that guy is a character.” But an actor like you has to become the character. So what is it like working with someone like Dennis Hopper, actors who don’t really have to push themselves into some other world; they can just kind of be who they are?

OLDMAN: Well, I certainly look at people like that and think, “Christ, I have to do all this work.” [laughs] Obviously, in the same way that blues musicians have influenced your songwriting and your playing, I look at my heroes’ work: Alan Bates, Tom Courtenay, Albert Finney, and certainly character actors like Alec Guinness, who I admired enormously. But my taste is very wide. I love Cary Grant. I love the absolute simplicity of Gary Cooper. I also look at Newman and McQueen and even Redford. I mean, if you watch Redford in All the President’s Men [1976], it’s one of the greatest screen performances.

WHITE: Tell me why.

OLDMAN: It’s in the eyes. He’s not traveling away from himself vocally or physically, or doing all the pyrotechnics. There’s something about the psychology. I will always say this to students of acting—we talk about phone acting.

WHITE: What is that?

OLDMAN: There’s an example in Darkest Hour when I’m on the phone with Roosevelt. Often you’re not speaking to the other actor; someone is reading the lines in the room or you’re not even getting any of the feed. There are people who are very good at it and people who are not good at it. In All the President’s Men, there is one take of Redford switching phones, talking to different people; it’s about six or seven minutes long. Very, very slow push in on Redford. And I would say to students, “You want to see phone acting? That is the Michelangelo of phone acting.”

WHITE: I know the scene you’re talking about. He’s switching back and forth between two people who are trying to stonewall him. That is a long scene.

OLDMAN: It’s beautiful stuff.

WHITE: I have a fun thing for you to try next time you’re at a coffee shop or in an airport. People have these Bluetooth headsets where it looks like they’re talking to themselves, but they’re really talking on the phone. I think you should say as loud as possible, “Hold on one second, I’ve got another call.” And then switch into a Russian accent and say, “Hold on, I’ve another call.” And then switch into Winston Churchill, and see if anyone catches on.

OLDMAN: [laughs] I’m going to try that in Starbucks when I’m in the line. It’s funny you mention being out and about. As an actor, you people-watch, you observe. And the more famous you become, the sad thing is you lose the ability to do that. Instead of people-watching, you become the focus of attention.

WHITE: I think Bob Dylan said that you can look into the window of a restaurant and everyone is being normal, and then you walk into the restaurant and everything changes, and you don’t get to see people being normal anymore. You might as well just leave. [laughs]

OLDMAN: I went to a crowded restaurant many years ago in Manhattan with David Bowie. And, oh my god, talk about atmosphere change.

WHITE: I bet. But you do a great job of disguising yourself in everyday life.

OLDMAN: Yeah. You might find this, too: if people don’t expect you to be there, they don’t see you. I’m sure that you’re recognized, but sometimes people might do a double take and then move on.

WHITE: Right. “Why is he buying rat poison at the hardware store right now? I mean, there’s no way he could be committing a murder.”

OLDMAN: [laughs] You can always say, “I’m researching a role.”

WHITE: I wanted to ask about whether you think we’re at a pinnacle of how far you can really go in the art of acting before the next generation, the future of acting. It seems like we’re going to see more of what was done with Jeff Bridges in Tron: Legacy [2010], where a younger version of his face was CGI’d onto another person’s body. Where do you see that going? Could you see yourself working 15 years from now in a world where everything is digital?

OLDMAN: In 15 years’ time, I hope to have hung up my gloves.

WHITE: I hope not.

OLDMAN: I’m like you in that I’m an analog guy. As you know, I like wet plate photography.

WHITE: Real film.

OLDMAN: It’s emotional. It’s got soul to it. And I know that you’re a big proponent of this because I think you single-handedly made vinyl a real thing again.

WHITE: Well, sometimes I had to use my other hand, too. [Oldman laughs] I don’t even know what that joke means.

OLDMAN: I’m a little scared of where it’s going. If you take a movie like Dunkirk—Chris Nolan likes to do a lot of in-camera stunts. I believe the boat that sinks in Dunkirk is a boat that is sinking. I think that just adds to the enjoyment of the movie. He uses digital to enhance and complement only where he needs to.

WHITE: And that’s what it should be used for. What’s also interesting about Dunkirk is that the movie came out shortly before Darkest Hour, which is an amazing exploration of just a few weeks of Churchill’s life, and historically, both stories were happening at that same time. How cool is that? What an incredible one-two punch of historical, World War II–based films.

OLDMAN: It’s funny how it’s in the zeitgeist.

WHITE: I love that the film just focuses on this one period in Churchill’s life. You learn a lot by analyzing a brief moment in time. You see how important Dunkirk was and how quickly and easily Britain could have been invaded. If England had been invaded and America wasn’t then able to come over and land planes, who knows what would have happened? It could have been horrendous.

OLDMAN: When they did test screenings of the film for different audiences, would you believe that, not only in America but also in England, very few people knew the story of how close we came?

WHITE: Isn’t that wild? If you really look at it, moments like Dunkirk or the Cuban Missile Crisis are so pivotal and close to the end of humanity as we know it. And now we have North Korea and Trump … Carl Sagan would often say, “The sky calls to us. If we do not destroy ourselves, we will one day venture to the stars.” People are enamored by the idea of, “Oh, we’re going to travel to other worlds.” But the first part is the most important. “If we don’t destroy ourselves.”

OLDMAN: Churchill knew this, almost like a prophet. He could see that technology was influencing weaponry. There is an essay he wrote in 1924 called “Shall We All Commit Suicide?” In it, he wrote, “Death stands at attention, obedient, expectant, ready to serve, ready to shear away the peoples en masse.” And after the war, he said about the nuclear arms race, “All you are going to do is make the rubble bounce.” There was no hope in it. Despite his best efforts, we still had the war.

WHITE: I love how the movie explores all of that and shows people what could have been. You learn a lot about who Churchill was through your brilliant performance of him. What a bizarre character he was. At times, he was an incredible speaker, and other times he was almost like a grumpy old man in the corner of a pub.

OLDMAN: He had a great relationship with the public. He was very honest and very up-front. Churchill said in a speech, “We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering.” He’s not saying that there won’t be enough bananas on the table; he’s telling the people that this is going to be very ugly. And the people loved him for that. I heard a story once that at a gathering of former British prime ministers, the conversation came around to Churchill, and there was a Churchill scholar among the group. One of these prime ministers—I don’t know who it was—said, “Who wrote Churchill’s speeches?” And the scholar said, “Well, he did.” And this ex- prime minister said, “How on earth could he have written his own speeches? How could he possibly have had the time?” And the scholar said, “It’s probably not the answer you want to hear—he was a genius.” He was just one of those incredibly gifted people who had an amazing brain.

WHITE: And passion. When you have passion, there’s all the time in the world. You make the time.

OLDMAN: I’ve never heard it put so well.

WHITE: My speechwriter wrote it for me.

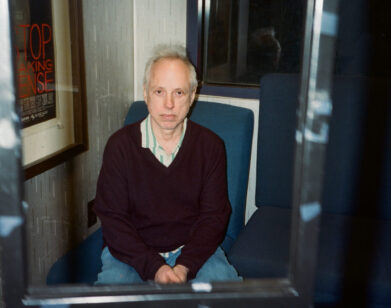

JACK WHITE IS A MUSICIAN, RECORD PRODUCER, LABEL HEAD, AND ACTOR. A FOUNDING MEMBER OF THE WHITE STRIPES, THE RACONTEURS, AND THE DEAD WEATHER, HE IS CURRENTLY AT WORK ON HIS THIRD SOLO ALBUM.