French heartthrob Louis Garrel thinks Godard is the Picasso of film

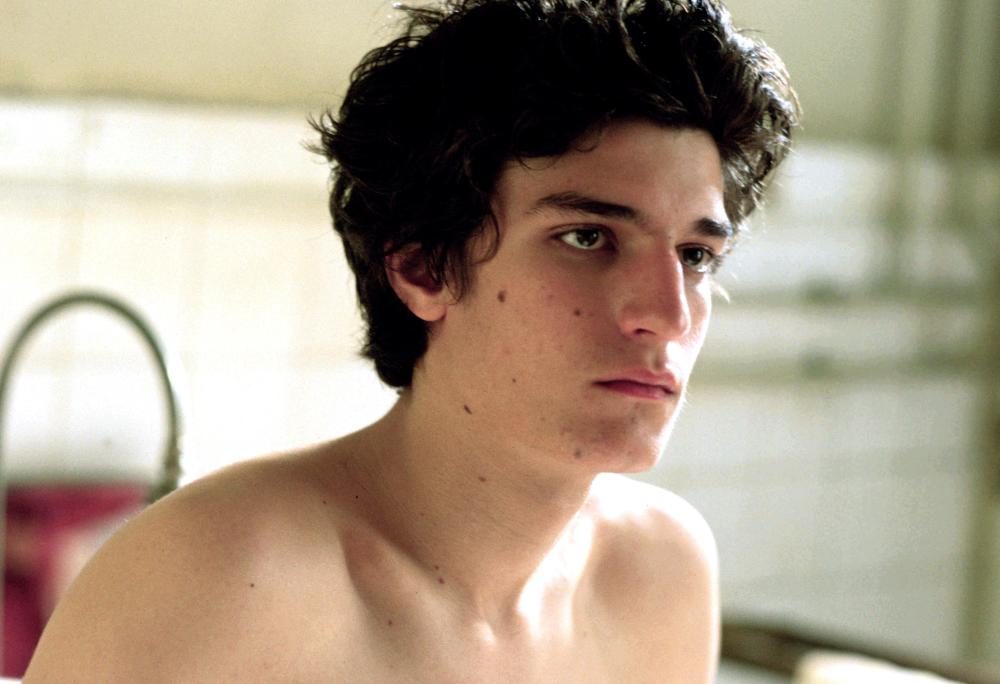

THE DREAMERS, Louis Garrel, 2003, (c) Fox Searchlight

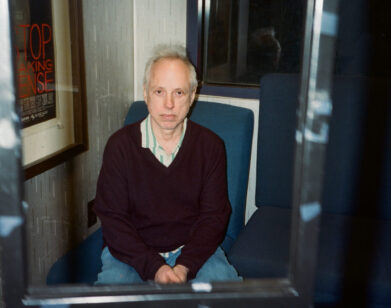

Of all the actor-directors you could think of to portray Nouvelle Vague legend Jean-Luc Godard, aquiline-nosed heartthrob Louis Garrel seems like a natural fit. Not simply because their physical resemblance is uncanny. (Seriously, it’s worth a side-by-side comparison.) Garrel had to carve a bald patch into his scalp and speak with affected inflections in The Artist director Michel Hazanavicius’ new biopic, Redoubtable. A far cry from Garrel’s typical casting as a male object of desire.

Garrel, like Godard, has always broken the rules. For one, he’s practically never dipped a toe in France’s huge, escapist entertainment industry. His two breakthrough roles, in Bernardo Bertolucci’s erotically charged The Dreamers (2003) and Christophe Honoré’s controversial My Mother (2004), explored complex, ambiguously incestuous relationships and called for full-frontal nudity.

The 34-year-old grew up in an indie film bubble that Godard himself made possible decades earlier. His father Philippe is an unsung Nouvelle Vague auteur who regularly casts his son in his understated black-and-white gems. His mom Brigitte Sy is an actress and activist playwright while his late granddad Maurice was an acclaimed theatre and film thesp. His godfather—Jean-Pierre Léaud—played the iconic turbulent child in Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and his younger sister, Esther, turned heads in Call Me By Your Name.

But the best reason to cast Garrel as the six-time Cannes-selected maverick? His borderline obsession for the man. “I binged on his films so often that I can’t imagine anyone not knowing who he is,” Garrel told Interview at the Toronto International Film Festival. In fact, it’s nearly impossible for him to pick favorites. “There’s Pierrot le Fou (1965), a magnificent film that’s like a Rimbaldian poem. There’s Bande à part (1964), which is very Truffaut-esque with its two guys, one girl set-up. Very few of his films don’t interest me. I mean, he’s the inventor of modern cinema. He transformed film language. At a time when French cinema was starved for air, he completely reshuffled the decks. He’s the first to have injected painting and poetry into cinema, making him the Picasso of film.”

Redoubtable marks a departure for the actor, one of his very rare forays into the realm of comedy, based on the novel Un an après (“One year later”) by Godard ex-wife and former muse Anne Wiazemsky. After the pair made La Chinoise (1967), about a bunch of bourgeois students turned Maoist revolutionaries, both the book and film chart their failed marriage, as Godard swiftly turned his back on everything that had made him so famous to embrace the radical politics of the May 1968 student uprising in Paris.

After The Dreamers‘ sensual revolution and his father’s existentialist Regular Lovers (2005), Redoubtable marks Garrel’s third stab at depicting the May 1968 riots. The film recounts how Godard campaigned to interrupt the 1968 Cannes Festival in support of student and worker groups. In the process, he also turned his back on traditional cinema and began churning out heavily political films. “It is quite strange to have broached May 1968 so often,” ponders Garrel in between drags of his vape pen. “I even made a little nod to it in my own film [Two Friends]. But my generation doesn’t often stop to think about what life was like prior to May 1968. It was a padlocked society. People expressed themselves a lot less freely. So it was quite incredible for youths to experience such a radical and swift transformation, even if it ultimately wasn’t successful in achieving all of its goals.”

Redoubtable‘s portrayal of Godard as a brilliant but cantankerous, troubled and increasingly withdrawn creator has generated mixed reviews and hit a raw nerve in his home country, where Godard is still a god in the eyes of many. Doing the promotional rounds in France recently for the film’s theatrical release, Garrel sometimes found himself having to defend Redoubtable on roundtable talk shows. That’s something he was ready for. “You know, Godard is such a force to be reckoned with in France,” he explains. “People care about his cinema—me too, for instance. So when people see something they read as an attack on him, they don’t hold back. And I’m happy to defend it.”

Seeing Garrel, an outspoken lover of Godard, sell the film alongside director Hazanavicius (who acknowledges the man’s contribution to film history but isn’t nearly as effusive in his praise), has made for interesting television. It has given way to curiously funny moments of on-cam bickering, with Garrel describing their dynamic as “he’s a Montague, I’m a Capulet.” That said, both agree Redoubtable allows room for those who don’t see eye to eye with Wiazemsky’s point of view. “I don’t see it as a critique of Godard,” considers Garrel. “It’s the story of an artist who, all of a sudden, decided everything he’d done up until then was no longer valid. And people got really upset with him for that. I mean, it’s pretty shocking. For Godard to suddenly decide that Breathless was bad … As a spectator and a cinephile, that’s completely nuts to me! But if I put myself in his shoes, as someone who admires his journey, I get it. He didn’t want to keep making the same film over and over. He wanted to shake things up.”

Garrel wonders whether Godard will screen Redoubtable. “It doesn’t make me anxious,” he says with a smile. “But I am rather curious whether he likes it or not. A part of me enjoys thinking he might have a critique of it.” And while Garrel champions Godard for “making actors sexy and charming” thanks to performances such as Jean-Paul Belmondo’s in Breathless, he acknowledges today’s kids don’t necessarily have the same impassioned response to his films. If they know him at all, that is. “Twenty-year-olds today don’t have the same relationship with his films. Look at Xavier Dolan for instance,” he says, turning his attention to the Canadian wunderkind who tied for Cannes Jury Prize with Godard in 2014, and whom he brought up at the top of our chat, inquiring how his last film had fared in Quebec. “His cinema is worlds away from Godard’s, yet we all eagerly await every new project of his, like young people once did with Godard. He’s their star.”