PORTFOLIO

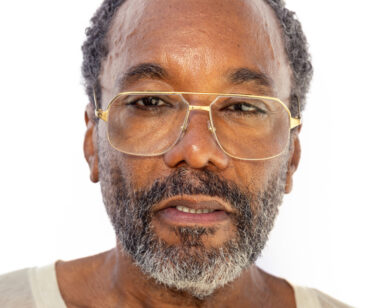

For Malcolm Washington, Directing The Piano Lesson Was a Family Affair

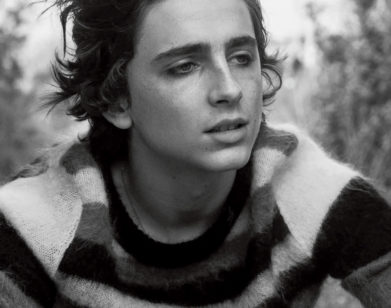

In an era when Hollywood retreads and corporate trends have become the backbone of blockbuster filmmaking, a crop of up-and-coming directors, unburdened by an adherence to Hollywood’s established norms and conventions, are approaching their movies with fresh, uninhibited perspectives. of ignorance in the face of industry conventions. Their work spans traditional genres, from coming-of-age comedies to sports biopics to prestige adaptations. Budgets range from streamer-funded to scraped-together. And while all of this results in different styles of filmmaking, their commonalities are much more salient. To find out why, we asked Eugene Kotlyarenko, filmmaker and host of the Director’s Commentary podcast, to speak with six early-career directors with big dreams and bigger ambitions. In the third of five installments, he talked to Malcolm Washington, the director of The Piano Lesson, a dynamic adaptation of AugustWilson’s timeless look at the impossible choices and family conflicts created by the dark legacy of slavery.

———

EUGENE KOTLYARENKO: Hey Malcolm, congrats on the film. Full of impressive stuff.

MALCOLM WASHINGTON: We took some swings, huh?

KOTLYARENKO: For sure. I love how it starts in that 4th of July sequence, juxtaposing two different Americas, through the lighting and sound design of the fireworks. I thought that was brilliant. Just knowing the source material as this great August Wilson play, did you feel the pressure to make something that was explicitly cinematic?

WASHINGTON: I think that word means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. It’s a slippery term, but one of the ways I was thinking about it was using the tools of film to get into the interior life of each character. In a film we can subvert the limitations of the stage. We can try to root you in somebody’s experience of the thing and then flip that 20 minutes later. A lot of times I was focusing on the quieter moments, or the person listening rather than the one talking. Controlling who and what the audience pays attention to. And conceptually, there’s a lot we did throughout making soundscapes and sound design to give multiple layers to each scene.

KOTLYARENKO: Do you play music?

WASHINGTON: I’m a big music lover, but the kind that has no talent in it.

KOTLYARENKO: Ha. Same. But maybe it helps us appreciate it more.

WASHINGTON: That’s what I think. I’m not burdened by the toll of knowing. It’s magic to me.

KOTLYARENKO: This is the third entry in the August Wilson adaptation project, after Fences and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

WASHINGTON: Right. I view this like a quilt where all these filmmakers bring their worldview to it, and I thought music was a big way to bring my perspective to the project and make something that a young person could be connected to.

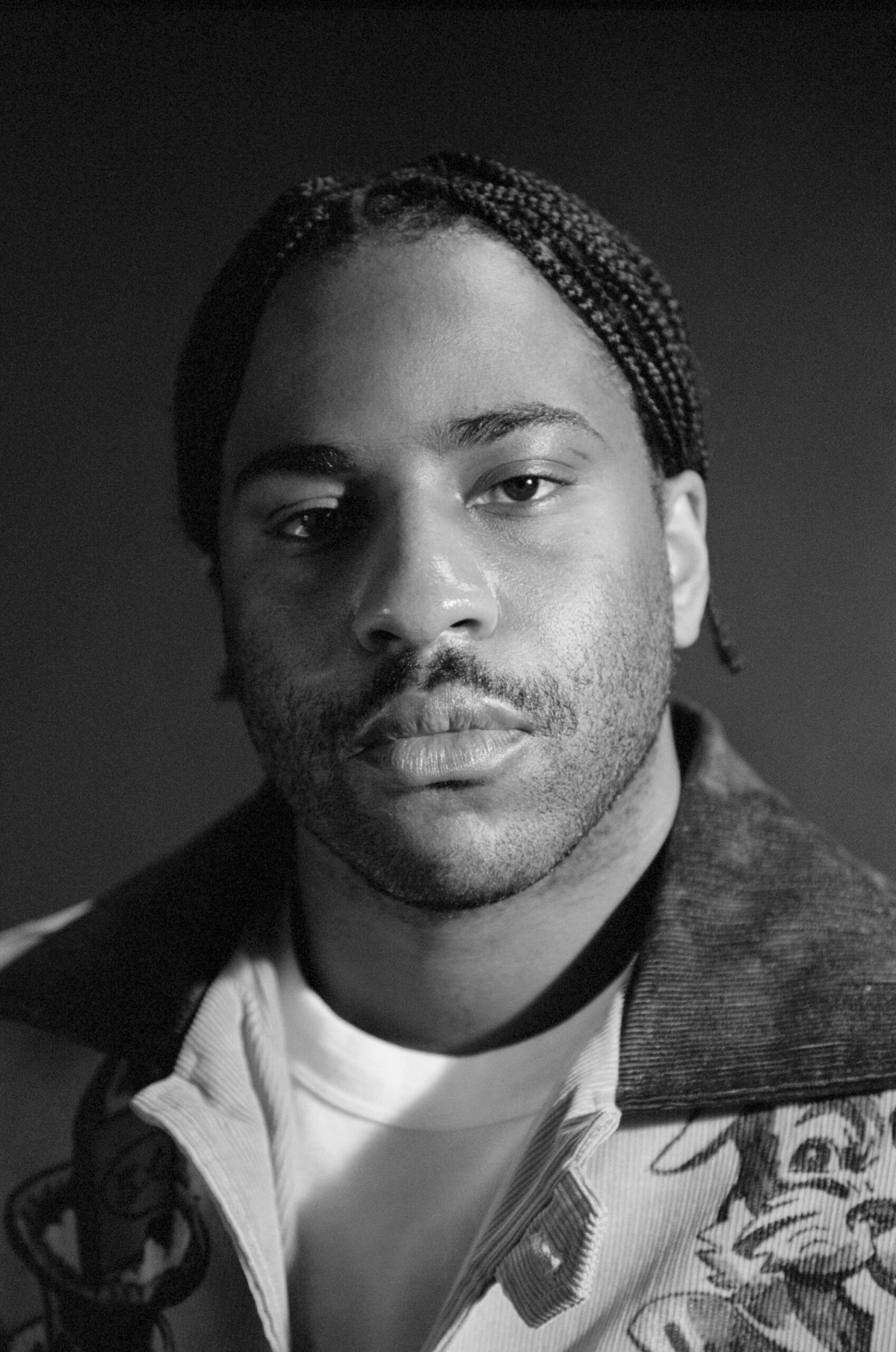

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah, it’s kind of your dad’s [Denzel Washington] big project to honor Wilson’s body of work. And I know on this film besides your dad, your sister Katia was a producer too, right? And obviously your brother John David is one of the leads. So I wonder, with a film that grapples so much with family legacy and sibling conflict, was it amazing to make it with your family? Were there unforeseen challenges?

WASHINGTON: Honestly, with the themes of the movie, having family around was perfect. It set a tone Sam Jackson and Michael Potts and Danielle Deadwyler, we all became family, because that’s what everybody understood we were walking into.

KOTLYARENKO: But families sometimes argue or have rivalries. The director-actor relationship is sacred and intense. Were there moments where you had to push back against your brother? What’s your guys’ age difference?

WASHINGTON: He’s seven years older than me, so when I was coming of age, he wasn’t around. In a lot of ways we connected so much on this film because time kind of collapsed and we just caught up and were looking at each other eye to eye.

KOTLYARENKO: Once you hit your thirties the gap doesn’t matter. That’s awesome.

It’s really a family affair and it’s really nice to feel that, because grappling with these complex family issues requires nuance. Obviously this is very specific to the African-American experience, but at the same time, I’m an immigrant…

WASHINGTON: It’s pretty universal, though.

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah, totally. My parents made a ton of sacrifices to settle us here, so inevitably they have certain hopes and expectations from their kids. And then that child is in a difficult position, because you do want to honor their sacrifices, but also want to have freedom over your own life path.

WASHINGTON: Exactly. The Piano Lesson is dealing with the Great Migration, and that’s why I think what you’re saying resonates so much, because for a lot of Black Americans in my generation, our grandparents all have ties back to the South, and that becomes our old country nd the traditions and superstition and way of life that comes with it. This story is about what comes with us and what gets left behind.

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah, and you feel that tension at the beginning when they get to Pittsburgh, and Bernice’s face when she’s like, “No, we don’t want the South up here.”

WASHINGTON: Yeah, or when Avery’s character comes into the movie and he’s reminded of these hooligans that he thought he got away from.

KOTLYARENKO: I was on a panel with someone yesterday, and she was like, “I was born in L.A. so I felt like it was my responsibility to become an actress.” Did you feel like that?

WASHINGTON: That’s so funny. The industry is all around you if you grow up here, and I loved movies, always. I loved watching them, but I kind of thought that the only thing you could really do in movies was act, and I didn’t want to act.

KOTLYARENKO: I wonder where you got that idea from. [Laughs]

WASHINGTON: [Laughs] Exactly. And then I got to college and learned that you could study them, and I was like, “What? There’s an intellectual element to this.”

KOTLYARENKO: Did you have a film at college that cinepilled you?

WASHINGTON: Cinepilled is so good. Okay, so there are two different movies. The one that made me be like, “Whoa, there’s levels to this shit,” was the Dekalog by [Krzysztof] Kieślowski.

KOTLYARENKO: I love the Dekalog. Any of the episodes stand out to you?

WASHINGTON: The fifth one’s my favorite.

KOTLYARENKO: Which one is that?

WASHINGTON: Thou shall not kill. It positions two deaths, where this guy gets in a fight with a taxi driver and kills him in the first half, and then the second half is about the state prosecuting and killing him. One’s this like random crime and the other’s this kind of systemic…

KOTLYARENKO: Mechanism of murder. Yeah, wow. I think my fave is the one where the guy programs his computer to answer all his questions.

WASHINGTON: And then the computer becomes like god.

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah, thou shall have no other idols or something like that. It’s pretty tragic.

WASHINGTON: But the Dekalog was one where it’s like, “I’ll probably never be smart enough to make something like this.”

KOTLYARENKO: I know the feeling. Why should I ever make a movie when there’s something that’s so good and so perfect? It’s inspiring, but it’s also intimidating.

WASHINGTON: Yeah, there’s some stuff that’s so good, it’s like, okay, I’ll retire.

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah, I’ll retire before I start.

WASHINGTON: The other one was a movie that when I saw it people trashed it in the theater and I saw it with my mom, and we were both crying.

KOTLYARENKO: I love that.

WASHINGTON: And so it made me be like, it’s okay to like something that everybody hates or that the people around you don’t like.

KOTLYARENKO: And that movie is called?

WASHINGTON: The Tree of Life.

KOTLYARENKO: Ah, The Tree of Life.

WASHINGTON: I just had never seen anything like that before. It felt so big and intimate at the same time, where it’s dealing with these gigantic questions at a time when I was also coming of age and I’m starting to consider who I am as a person.

KOTLYARENKO: Totally. You can feel the influence of The Tree of Life in your film, for sure. Tonally, imagery-wise.

WASHINGTON: Yeah, and the cutting style of it, and disconnecting sound and image, but having them be spiritually connected. There’s another filmmaker called Kahlil Joseph who I’m a really big fan of, and it feels like he’s the next iteration of Malick in a lot of ways.

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah, he’s amazing.

WASHINGTON: I’m programming his first movie Until the Quiet Comes with Moonlight at the Egyptian in L.A. Netflix asked me to make a rep series around the film.

KOTLYARENKO: That’s awesome. I’m always fascinated by first films. I think Leos Carax said something like, “The first movie is the only movie you ever get a chance to be preparing for your whole life.”

WASHINGTON: That’s totally right. And so many people have been saying to me “Oh, for your first movie, you took a big bite of the apple.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but I’ve had 33 years of ideas.” I’m like, “I was trying to be restrained with all the ideas I had.” [Laughs]

KOTLYARENKO: And you can feel that it’s jammed with ideas, and guess what? You get all that out in the first one and then you’re like, “Oh yeah, I have a gazillion more ideas.” Artists keep generating them.

WASHINGTON: Yeah. How do you find that process of moving from your first one to your next ones?

KOTLYARENKO: I usually react a bit against the previous one. But inevitably, because you really only have one voice, you’re going to end up doing your thing. But I think you at least have to chase something different to be sane and challenge your creativity.

WASHINGTON: It’s like, you think it’s totally the opposite and then you look up and it’s the sequel.

KOTLYARENKO: [Laughs] Yeah, inevitably it does still show your signature. I also try to get going as soon as possible, I think that’s super important.

WASHINGTON: A friend of mine just told me that today. He’s also a filmmaker. He’s like, “Get back to work. Don’t wait.”

KOTLYARENKO: I mean, you’re going to have to do all this press and shit, but it’ll be cool if the day of the release you are in the middle of a script or have a script finished, because that’s when you’ll be real hot and everybody will be celebrating you and you’ll be like, “You like that? How about this?”

WASHINGTON: Yeah. Okay, I need to get to work. I gotta go. [Laughs]

KOTLYARENKO: Looking forward to the next one. Thanks!

WASHINGTON: It was a pleasure, man.

———

Special thanks to The Film Gods.