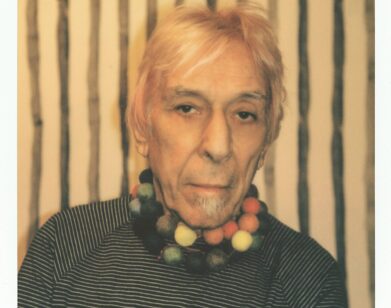

Floria Sigismondi and Dakota Johnson See Each Other In the Darkness

It was only a matter of time before Floria Sigismondi made a horror movie. A multidisciplinary artist in the truest sense, Sigismondi first made her mark by terrifying unsuspecting teens with the nightmarish video for Marilyn Manson’s single, “Beautiful People.” Her subsequent music videos, for artists like Rihanna, Bjork, and David Bowie, never quite reached that level of phantasmagoric excess, but they did showcase a visualist who was able to draw on her background in painting and photography to create images that lingered in the subconscious.

Now, a decade after her feature film debut, the rock biopic The Runaways, Sigismondi has returned with The Turning, a modern adaptation of Henry James’s 1898 horror novella The Turn of the Screw. In the ‘90s set movie, Mackenzie Davis stars as a nanny who heads off to an eerie estate in the Maine countryside to look after two orphans (played by Finn Wolfhard and Brooklynn Prince) who may or may not be harboring dark secrets (spoiler: they probably are). While the film’s premise sounds like your standard horror set-up, Sigismondi had more on her mind than jumpscares, using her characters’ arcs to explore themes of trauma, abuse, and toxic masculinity, shot through a feminist lens. Here, she connected with her neighbor Dakota Johnson to discuss the mechanics of horror from a woman’s perspective, and truths that don’t always set us free.

———

DAKOTA JOHNSON: Hi, Floria.

FLORIA SIGISMONDI: Hi, how are you doing?

JOHNSON: I’m doing pretty good. I’m at my house in L.A. Where are you?

SIGISMONDI: I’m in L.A., too.

JOHNSON: Oh, come over. Where do you live?

SIGISMONDI: I’m in Laurel Canyon.

JOHNSON: Me too!

SIGISMONDI: That’s really funny.

JOHNSON: I’ve seen so many of your videos, and I just directed a music video, my first one. I’m very honored to hear that you even know who I am.

SIGISMONDI: Congratulations. We’ll have to get together and talk about that experience.

JOHNSON: I would love that.

SIGISMONDI: It’s a different beast. It’s fast and furious, and normally takes place in a day.

JOHNSON: It’s totally insane. What makes you decide to make a feature? I’m sure you had films or scripts that came your way over the years, but what makes you decide to make a movie?

SIGISMONDI: I go where the creativity is. I’m an experimentalist at heart, so I put myself in situations that are a little bit different than I previously experienced. I’ve been fortunate to work in different mediums, whether it’s a Gucci campaign or a music video for Rihanna. What drew me to this project in particular is the book. I read it when I was a teenager, and there was something so great about it, because you could read it one way and it’s a ghost story, and then you read it another way, and it can be interpreted completely differently, as a woman going mad.

JOHNSON: I haven’t read the book, but I’m sure there are some visuals that are in the book that you put into the movie, but were there scary or dark things that you summoned from your creative brain?

SIGISMONDI: The book was written in the 1800s and I wanted to modernize it. I set it in the ’90s because I thought, let’s get rid of technology so she can’t look things up and call for help. It’s a very POV story, so I was able to play with her nightmares. That’s where I put a lot of me into it—her nightmares and fears and her psychological frame of mind.

JOHNSON: I feel like I haven’t really seen this kind of genre film before from a feminine psychological viewpoint.

SIGISMONDI: If you look at horror films—especially in the ’80s when it was all slasher flicks—and the females were screaming and running and feared for their lives. I wanted to do something that really took you into their mind. What teeters somebody over the edge? On the surface it’s about a young woman who goes to take care of a family. Her mom’s in an institution and she’s had some trauma in her life. But on a deeper level, you start to see that it’s a bit of an allegory for what women go through, because one of the two kids that she’s been hired to take care of is a young boy who’s played by Finn Wolfhard. I kind of upped him from the book because there’s this great opportunity to create tension between her and this boy. He’s at that age between boyhood and manhood. I really love taking two opposite things and creating tension through that. He has been passed down this masculine toxicity, so he doesn’t know how to behave. He’s got this strange way of behaving, and it spirals her into madness. It’s about the outside world and how a woman has to navigate it, and how if you tell the truth, that you could be perceived as mad.

JOHNSON: Right.

SIGISMONDI: There’s an older character, the housekeeper, and she represents the woman who just sweeps things under the rug. It’s better if you don’t talk about it. If you don’t talk about it, it didn’t happen. Kate’s character, who’s played by Mackenzie Davis, is really about, “This is what I think happened.” If you carry darkness within you and don’t deal with it, it’s about what happens to that, which I think is so relevant to what you’re doing with your podcast The Left Ear. It’s so beautiful.

JOHNSON: Oh god, thank you.

SIGISMONDI: You’re giving these women an opportunity to tell their stories in an anonymous way and just get it off their chest. It’s holding something, harboring something, and how dark that can become and how far away from you you can become.

JOHNSON: It so depends on how the people around you react to it. That kind of dictates the direction you’ll go in for the rest of your life, like the different characters in your movie perhaps, representing the different ways that you can deal with trauma, or that you can not deal with it. When it comes to something like The Left Ear, when it’s about sexual violence in any way, the way others react is so detrimental and will dictate how the person who experienced the trauma will heal or recover, or if they do.With The Left Ear my initial goal was to create a space where women or men could tell their stories of abuse and harassment and sexual violence without any kind of judgment, without being pacified, without being criticized, without being diagnosed or broken down or ignored. I wanted to create the podcast so that people could listen without having to speak, without having to completely jump to judgment. I learned that is not something that’s easy for people to do. It was so shocking, but the numbers dropped by the thousands after the first episode because I think it was a little bit too hardcore and too raw and not padded with advice or pillows of how to absorb this information. I think it leaves you feeling like you’re left with this information and you don’t know what to do with it, and perhaps it’s triggering to your own trauma or perhaps you feel like you need to help and you can’t. It’s this really tricky fine line of how do we evolve, in a way larger scope, the conversation around sexual abuse and even sex as it is?

SIGISMONDI: I think that’s the biggest fear for women, and this is kind of a little bit what my story’s about, too. You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

JOHNSON: Totally.

SIGISMONDI: The fear of not being believed and what that can do to you. It can drive you crazy if the outside world is not believing something that’s happened to you. If you can help those women get it off their chest, get it out of that deep place that’s been locked up, then that’s the goal. I don’t think it’s about the therapy. That’s the therapy.

JOHNSON: I came to that realization as well, because the thing that I also didn’t want to do was make it entertainment. By adding so much explanation and other people and conversation, I’m not trying to entertain you. I’m trying to help people.

SIGISMONDI: You can hear it in the women when they’re thanking you for the opportunity to speak about it.

JOHNSON: It was really hard to listen to thousands of voicemails where people would speak to me directly and address me by my name.

SIGISMONDI: Something that dark that you’re holding, there’s always this thing, “What if people know that I’m wounded?” There’s that thing that you’re hiding constantly.

JOHNSON: Do you ever feel that? When I look at your work, you expose a side of yourself that I would feel really vulnerable about exposing. If I were to illustrate my darkest thoughts or the things that come to me in the night, I don’t, because I’m like, “What would it look like?” In that aspect, I care what people would think, but I respect what you do and what you create. “My darkness sees your darkness.” Is that scary for you?

SIGISMONDI: Because I’m speaking in images, I’m more fearless when I create that way. If I miss an opportunity to do that, I’ve missed a breath in life. It’s constantly about taking advantage of every moment that I’m alive. It’s sort of like I’m swimming in an ocean of images and I just grab onto these things and don’t think about it too much.

JOHNSON: Right.

SIGISMONDI: I feel an urgency to create. I don’t know it when I’m doing it, but I learn about myself in creating. It’s more about a spiritual adventure than it is putting pictures up for people to judge.

JOHNSON: And you paint as well, right?

SIGISMONDI: Yes. I try to keep that up constantly because for me, it’s the exercise of the intuitive in a beautiful way. When you’re painting, you don’t think of, “Oh, is this line supposed to be crooked or straight? Is this my last brushstroke?” There’s none of that. It’s a subconscious act of the inner world and outer world. I try to exercise that as much as I can, because on set, that’s what I’m doing constantly. You’ve got to almost ignore the thousands of people that are there, and just kind of go, “Okay, what do I need to do intuitively? What is the right choice? What’s the right color? What do I need to tell the DP?”

JOHNSON: Have you always been that way? Because I imagine you’re taught that lines are supposed to be straight. How did you unteach yourself that and let your intuition guide you more than your analytical mind?

SIGISMONDI: I think when I really started listening to myself was when I did Marilyn Manson’s “Beautiful People” video. I remember the night before the shoot, I went, “Oh my god. Am I really going to do this? This is so crazy and out there.” I started to feel the eyes of the outside world, and that’s when I went, “Oh god, that’s dangerous.” That’s a dangerous place to go because creativity comes from such an inner place, and that’s what excites me. It’s teaching myself to go with the excitement, to go with that little butterfly, to go with that little love that you have. When I met David Bowie is when I thought, “Oh, here is an entity, a spirit that is completely navigated by whatever he wants to do.”

JOHNSON: Yeah.

SIGISMONDI: I remember handing him an edit and the record company wasn’t happy with it, and I told him, and he just laughed at me and said, “Floria, it doesn’t matter what they think.” I just went, “Oh my god, you are so free.” He’s not thinking about how he’s being perceived in the world and that’s what makes him so special. It’s hard to always live by that, but it’s always great to be reminded, because at the end of the day, we die. Life runs out, and how authentic do you want to be to your spirit? How important is that happiness to you?

JOHNSON: I totally believe in that and I totally believe in you, completely. There’s a kind of throughline with the artists that you’ve worked with. They’re all mavericks in their own way, like Bjork and Leonard Cohen and obviously David Bowie. You’ve worked with some of my favorite artists of all time.

SIGISMONDI: That’s great. It’s not like I set out to work with these artists. Those are the opportunities that were presented to me. I go where the creativity is. In Suspiria, you had to go to places that you have probably never gone to because it’s about a woman who comes into her own power. Are you in the zone when you’re doing those things? Are you in a place where you kind of forget where you are? The movie feels like a trance.

JOHNSON: It feels like witchcraft is being performed on you as the viewer. The whole preparation process and the filming process was really intense. In the moment, you switch in and out of being really in it, micro-focused on a certain emotion or a certain vibe, a certain energy and the intricacies of that specific thing, to then being pulled out and being on set and running around with a bunch of dancers and a bunch of women, and it was so fun and so just powerful and beautiful and raucous. Then I realized I was really playing with a lot of legitimate darkness. I let it into my heart. I don’t know if you meditate or if you do any sort of spiritual work, but I can go in and out of feeling like my connection to the universe is super strong and solid, and then I can go through phases where I feel like I don’t feel connected to anything. I don’t even feel any kind of tether to something magical.

SIGISMONDI: I do transcendental meditation, and Kundalini yoga. But for me, my spiritual practice comes hand in hand with my creative process. It’s like what you do when you’re acting. When I go there and I go deeper, that’s when I do my best work. Because it means something, even if I don’t know what it is. It’s just a fulfilling feeling.

JOHNSON: I know exactly what you mean.