NYFF

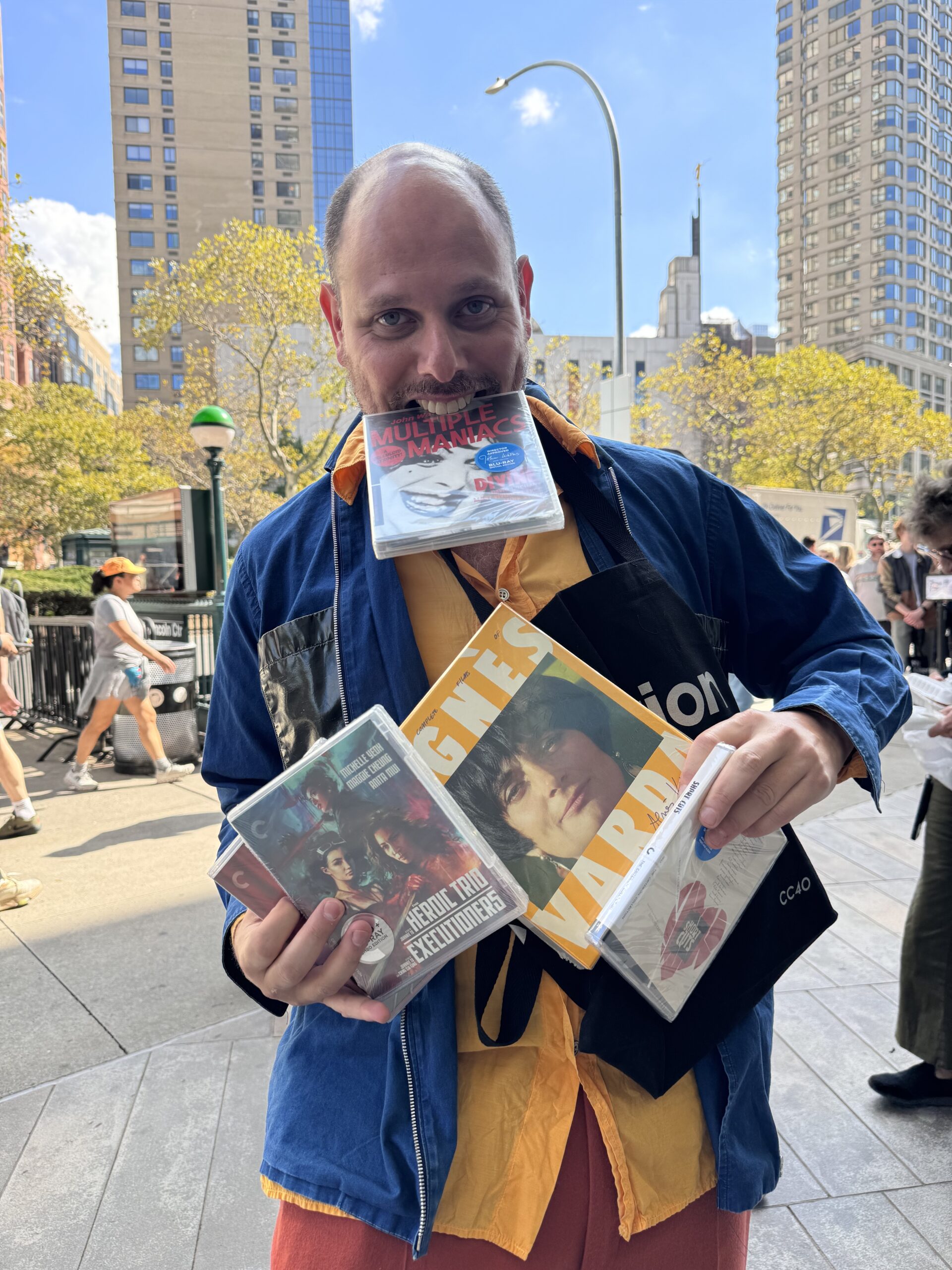

Filmmaker Eugene Kotlyarenko Gets Freaky in the Criterion “Bangbus”

Is love possible once the sex fizzles out? That’s the question at the center of filmmaker Eugene Kotlyarenko’s latest comedy, The Code. Set during a COVID-era lockdown, the satire stars a deadpan Dasha Nekrasova as Celine, an aspiring documentary filmmaker who’s determined to capture her flailing relationship with Jay, a paranoid crypto bro played by Peter Vack. The film features security footage and split screen montages, playing with ideas around consent and content creation while maintaining the dick-wagging humor Kotlyarenko is known for (there’s at least two full-frontal moments, not that we’re counting). To learn more about the campy, depraved flicks that inspire the L.A.-based director, our senior editor Taylore Scarabelli met Eugene for a quick ride in the Criterion Mobile Closet ahead of The Code‘s New York premiere at Roxy Cinema.

———

SUNDAY 12:36 PM OCTOBER 6, 2024 NYC

EUGENE KOTLYARENKO: Here we are doing a speed run through the Criterion Bangbus. Okay, this is as good as it gets. You want to cine-pill someone, you show them Agnès Varda, the poetry, the inspiration, the laughs. Beautiful stuff. I was lucky enough to work with Agnès on one of the films in here, and every single moment was an inspiration. What else? This is too hard. Everything in here is good.

TAYLORE SCARABELLI: Maybe you need to do roulette?

KOTLYARENKO: Okay sure. This is “extremely random,” Shortcuts, Robert Altman. This is the best portrait of L.A. and it ends in the nicest possible way—people dying. That would be a nice thing to happen to people in L.A. I’ve lived there for 17 years, so I’m speaking with authority.

SCARABELLI: [Laughs]

KOTLYARENKO: This is good. This will make you cry. Yi Yi. Edward Yang. I remember when I was like a teenager I would email Janus and Criterion and be like, “Please put out such and such movie.” So it will be awesome when Criterion puts out A Confucian Confusion and Mahjong, the Edward Yang ’90s movies. But this is inspiring. Makes you feel special about being alive. Okay, what else do we see here? This is cool. Multiple Maniacs. When something like this gets on Criterion, you feel good about cinema, about your own filmmaking. I just showed my new movie The Code in Baltimore—I’ve been showing movies in Baltimore for 15 years, and finally John Waters showed up. It was such an honor to have a conversation with him about the movie. He said it was sexy. And this is a type of sexiness. It’s a camp classic.

SCARABELLI: We love.

KOTLYARENKO: Okay, last one. The Heroic Trio/ Executioners, Johnnie To. One of the great living filmmakers. Awesome ass-kicking women. Just beautiful, fun, funny. Not taking itself seriously, but inspiring. Every year Johnnie To puts out a movie is a great year for cinephiles. Alright. Thank you guys for having me here in the bus outside of the New York Film Festival.

SPEAKER 4: Thanks for visiting us.

SCARABELLI: That was fun. I guess I should have done one. I saw Cat People in there. I probably could have just talked about that for five minutes. It’s not Schrader’s best, but I appreciate him being honest about tacking on a new ending so that he could keep Nastassja as a caged cat for eternity because he fell in love with her on set. Problematic but honest.

KOTLYARENKO: You know her famous quote about how she used to fuck all of her directors, but with Paul it was tough. [Laughs] I think Nastassja Kinski comes from a very specific background and upbringing that was really demented, because her father [German actor Klaus Kinski] was the exemplar of really unstable, bad behavior for an actor.

SCARABELLI: And she was, like, 18.

KOTLYARENKO: She was very young when she had that crazy five year run. She was in Tess by Roman Polanski. She was in Exposed, which is one of the most underrated movies ever made by James Toback. She was in Cat People, Paul Schrader. I mean, can you think of three more depraved individuals? No offense, I don’t necessarily use depraved as a pejorative. Especially when it comes to art that’s true and contradictory and human. Humans are depraved.

SCARABELLI: That’s true. But I feel like people are scared to make depraved films right now.

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah. I mean, you can make a film that’s really noble and depraved. One of the movies I was looking for in the Criterion bus that I couldn’t find is part of a Shohei Imamura box set. It’s called Insect Woman. And it’s about a woman who is abused and left to raise a child alone. You have incredible sympathy for her throughout the film as she becomes a prostitute and works in a brothel. And then halfway through the movie, she rises to power and takes over the brothel and becomes incredibly cruel. In fact, she becomes more cruel than anything done to her in the first half of the movie. And so, suddenly your allegiance and sympathy for her is completely flipped. You’re like, “How can you act like this?” It’s a depiction of a certain arc of human nature. That movie is actually quite noble and philosophical and deep and sad, even though it shows depraved behavior.

SCARABELLI: Speaking of depraved, I watched the Piano Teacher the other night. Similar kind of thing, but almost too moralistic for me.

KOTLYARENKO: I liked that movie a lot, but I wanted the second half of the movie to be like, is this a game or not? Because the way the guy’s exploiting her predilections and her weaknesses, you want to feel like, “Is this what she wants?”

SCARABELLI: I think you get that at the end though. During the rape scene.

KOTLYARENKO: I just wanted more mind games.

SCARABELLI: Yeah. I also just saw Babygirl, which was definitely informed by that film.

KOTLYARENKO: Well, power dynamics and consent, these are things that were real even before they became buzzwords. Every relationship is a balance between devotion and brainwashing.

SCARABELLI: True. So you have a movie that’s screening tonight—

KOTLYARENKO: The Code at the Downtown Festival. I would say it’s a depraved movie on the right side of history. It’s a movie about sex and love, and is love possible when the sex has faded? And is there a way to revive it? How do we fall in and out of love? Maybe there are games to play, especially in a world that’s full of surveillance and performativity. Is there a way to save love in a world where everyone’s the central character and trying to tell their own story constantly?

SCARABELLI: Is this a romance?

KOTLYARENKO: It is a romantic film, and it’s also an anti-romantic film in that it talks realistically about the death of relationships. I’ve made romantic films before. I think this is my most hopeful film. I think it’s kind of a wish fulfillment film for me—saying like, “Okay, how can you revive it after it dies?”

SCARABELLI: So you’re not giving up on love?

KOTLYARENKO: I’m not giving up on love, and I don’t think cinema should give up on love, but I think it is important to talk about relationships and love in a way that can be a little bit brutal. Even though it’s not easy to watch sometimes, it’s refreshing for people to see things that make them say, “Oh, I feel seen, I’ve experienced that.”

SCARABELLI: Is there anything in that closet that informed your film?

KOTLYARENKO: Well, one of the first Criterion movies I really liked was called the Honeymoon Killers, which is a one-off movie about a couple on the lam murdering people and exploiting each other. It’s funny, but it looks beautiful. It’s kind of like Badlands for campy queens, but five years before Badlands. Anyway, when you see stuff like that in the Criterion Collection, it gives you hope, because I’m a comedic director and people tend to take those films less seriously.

SCARABELLI: In your last film, Spree, you were playing around with different kinds of cameras, social media. Is that a big part of this?

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah. So Spree was about okay, could I take live-streaming, which I found to be such an interesting format for storytelling, and turn it into something cinematic? And this one is about a different kind of cinematic element, which is the edit. So in the film, one of the main characters, Celine, played by Dasha Nekrasova, is making a doc. And her boyfriend Jay, played by Peter Vack, is anxious that the doc will portray him badly. So he starts trying to take control of the movie by making his own counter movie. And so, the movie you’re seeing is this destabilized narrative with multiple perspectives on the same things, and you’re trying to figure out what is the truth.

SCARABELLI: Interesting

KOTLYARENKO: We used 70 cameras, some of them were hidden cameras, and then there’s this sense of them understanding there’s hidden cameras, so you don’t even know if what you’re seeing is authentic behavior or performative behavior. We all consent to be in a surveillance culture very casually and very thoughtlessly. And so the movie is saying, “Hey, if we accept that, then we need to figure out how to work through that and how to use it for our own benefit.” Because it’s so easy to say, “Oh, it’s evil. Cambridge Analytica is exploiting our data. The algorithm is controlling what I want. I’m being watched everywhere.” All of that stuff is true, but that’s the society we have built for ourselves. So is there a way to work through that and use it for our own gain?

SCARABELLI: You’re also talking about people having different sides of a story, and how you uncover “truth.” That makes me think of the Me Too era…

KOTLYARENKO: Well, the movie does take place in 2021 in the middle of lockdown, closer to the Me Too moment. And not to spoil it, but the Jay character has been canceled, which works into his sexual impotency and his fear of women. The film’s a satire, so it’s my privilege as an artist to make fun of people who are canceled, but also to make fun of the cancelers and the culture that cancels people. There’s this disgusting and distorted mechanism for destroying lives, and whether it’s valid or not, the fact that a mechanism for that exists is very sad. Just like the justice system is perverse and corrupt, even though it’s legalized, it often destroys people’s lives.

SCARABELLI: Using all those cameras, how did that affect the actors on set? Were you rolling all the time?

KOTLYARENKO: It’s really fun for the actors, because it’s more like they’re living in it. And Spree was like that too. It’s a kind of diegetic cinema where the characters in the movie are the filmmakers. They’re constantly in character. It’s like theater, but as long as the framing is good and you understand the relationship and how you’re going to edit it later, it’s highly cinematic. The other thing is, my movies have a lot of split screen in them, and so to have the different sources allows me to experiment with multiple screen images that can create a beautiful, new mise-en-scene.

SCARABELLI: That must’ve been an intense editing process.

KOTLYARENKO: We had two editors, Sabrina Greco and Tucker Bennett, and because we had almost no money, our camera crew was initially just two people, Bart Cortright, our DP, and Jake Garcia, the AC. There was no DIT, so every night after we were done shooting, Sabrina would organize and offload everything and then go to bed when we started the next day.

SCARABELLI: What was your budget?

KOTLYARENKO: It was small. I’ve made movies for $100, $5,000, $50,000. It’s not small like that, but small for a movie that has a lot of ambition.

SCARABELLI: Do you have a dream project you’d like to make next?

KOTLYARENKO: I’m trying to make a techno thriller in Japan. I’m most inspired by Japanese cinema, which has such a rich history, so I’d like to do something there that would feel like a contemporary homage to all the Japanese films that I love. I was also trying for a long time to make a conspiracy thriller about America’s favorite conspiracy theorist. A movie where it’s like an Alex Jones type character is suddenly the greatest prophet in America. And he’s like, “Wait a second, this can’t be true. Why is this happening?” And he starts investigating the conspiracy where he’s in the crosshairs. You can’t make that movie in Hollywood unfortunately. Maybe the winds will shift and people will realize not every character needs to be an angel, that it’s interesting to explore the darker sides of our culture.

SCARABELLI: I hope so. We’re ready. We haven’t had a good film about media prophets since Network.

KOTLYARENKO: Yeah. The last thing I want to say about being in the Criterion Gangbus or whatever—there’s an ominous phrase about the future, which is, “You will own nothing and you will be happy.” And yes, of course fetishizing Criterion discs is a way of intellectually justifying consumerism. But it’s undeniable. When you own physical media, it’s not going to disappear one day from a streaming service. And on top of that, the image is going to be super-high quality and the features on the discs will definitely inspire you. Criterion has this cult status not just because of the curation, but because of the special features, the commentaries. That’s the stuff that demystifies cinema and inspires a film lover to become a filmmaker. And when someone like John Waters gets in the Criterion Collection, it’s justice. It’s like a vindication that people do want experimentation, people do want a unique point of view, and they do want new art. And if they’re offered that they will embrace it as long as it’s fun.

SCARABELLI: Absolutely.