Ellen Burstyn Talks to Alex Wolff on Life, Death, and the Poetry of It All

Ellen Burstyn has won the “Triple Crown” of acting: two Emmys (Law & Order; Political Animals), a Tony (Same Time, Next Year), and an Oscar (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore). While playing the mother of a demonized daughter (Linda Blair) in The Exorcist, she suffered a permanent back injury after a scene where Blair throws her to the floor. In Requiem, her character—a lonely widow in Brighton Beach—gorges herself with chocolates in front of the television.

Fast forward to real time, and Burstyn—87 years young and now one of the active presidents (along with Alec Baldwin and Al Pacino) of the late Lee Strassberg’s Actors Studio—isn’t blankly popping sweets in front of a screen in her Upper West Side apartment. She reads copiously. At the time of this interview, she has just finished Physics of the Future by Michio Kaku, and she has a collection of poems on hand called The Rag and Bone Shop of the Heart. The title is based on a line in a W.B. Yeats poem, “The Circus Animal’s Desertion,” about a man with writer’s block who finally finds “his muse” not in mythology and fantasy, but in the detritus of loneliness and the scraps of his pain.

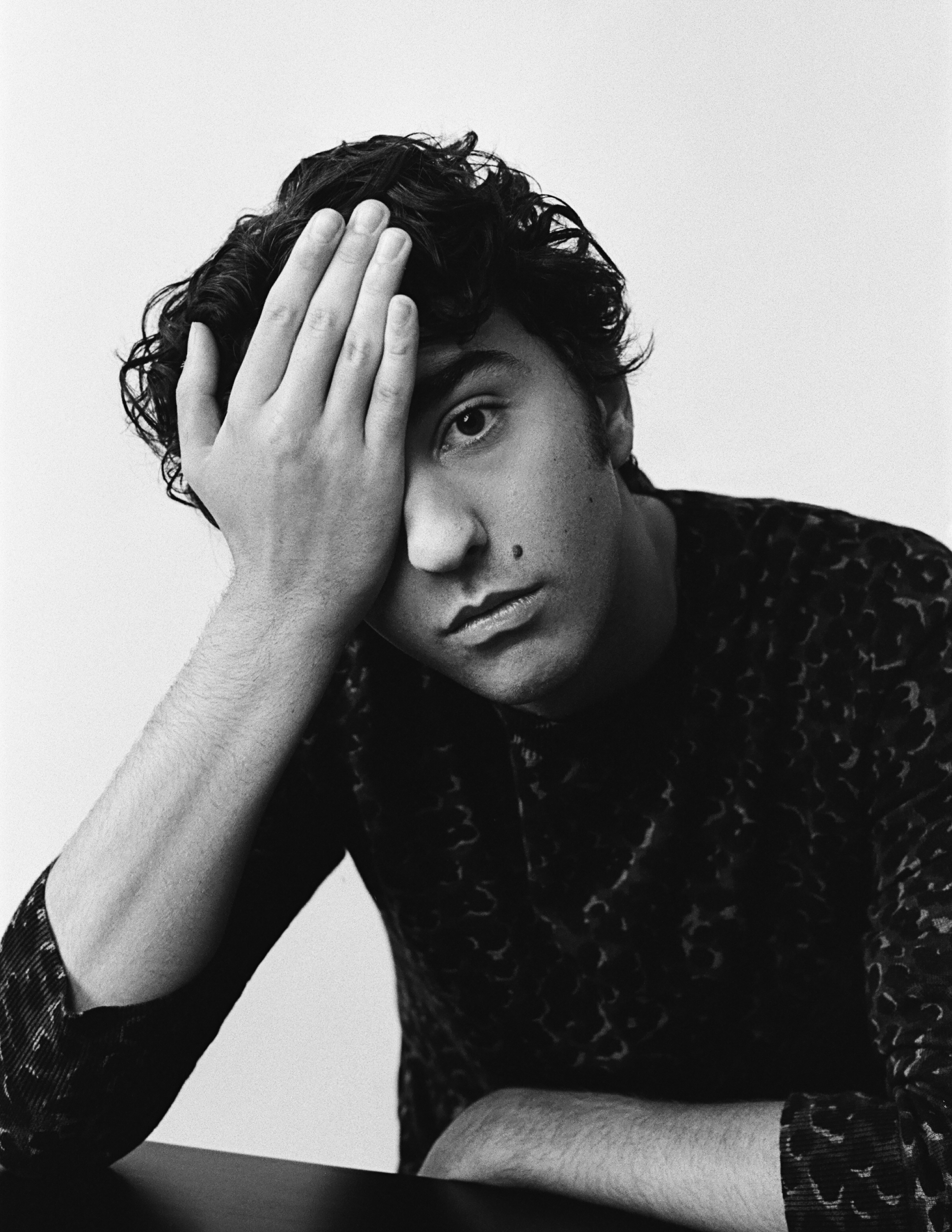

The book is fitting for an afternoon during which the 22-year-old actor Alex Wolff, of Hereditary and Jumanji fame, stops by. Wolff’s career began when his mother, the actress Polly Draper of Thirtysomething, produced The Naked Brothers Band for Nickelodeon, featuring Alex and his brother Nat. Wolff made his directorial debut at age 22 last fall with The Cat and the Moon, a coming-of-age New York story that he also wrote, about a high school kid who stays with a jazz musician colleague of his deceased father while his mother is in rehab in the Midwest. In the credits for his film, Wolff thanks both his cinematic and literary heroes, including Bill Evans, Sofia Coppola, and none other than W.B. Yeats—whose poem gave Wolff his title.

He sits at Burstyn’s piano and begins to play by ear while Burstyn brings out a pitcher of water, and later, organic berries and granola. They first met when the two were cast in 2017’s The House of Tomorrow, at which time they seemed to immediately recognize one another as a kindred spirit. —SUSAN KIRSCHBAUM

———

ALEX WOLFF: Well, it feels odd, Ellen, that you are interviewing me. I will say that. You probably have the best career of anyone in the history of the world with the most longevity. And the person who I feel has taken the most risks over the longest period of time. I remember seeing Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore when I was young and thinking that it was the best performance I’d ever seen. Then Requiem for a Dream, and thinking, okay, that’s the best performance I’ve ever seen.

ELLEN BURSTYN: We can have a conversation.

WOLFF: Working with you was probably the best experience of my life. It’s funny because you said you don’t even remember this, but I remember I was very nervous on one of my first days of filming House of Tomorrow, thinking, “I’m doing a scene with fucking Ellen Burstyn and I’m nervous, and I’m being rude to her in the scene and off camera.” The crew was making some noise, and it was my closeup. I think you could tell it was affecting me. You said, ‘Hey guys, quiet. He’s working, he’s working. Go ahead, sweetie.’ Like that.

BURSTYN: It wasn’t easy, and I would not expect a young actor to be able to fulfill it as completely as you did. I was really impressed when I saw you do a scene. My impression was, “Oh wow, who’s that?” Your talent shone like a searchlight. I respected you enough to silence the people. I respected you because of your talent. Your film title—The Cat and the Moon—that’s Yeats?

WOLFF: Yeah. The poem “The Cat and the Moon.” I was just moved by that image of a young cat looking up, lifts to the changing moon, his changing eyes. It feels like the changes of youth, that poem. That was the big thing for me. Also, I found that the imagery was very New York, spoke to my sensibility of lights and colors and the moon and nighttime. That was really my life, especially my teenage-hood—nighttime and being out on the streets of New York. Those two things were colliding. My dad as a jazz musician would always say, “Oh those are the cats. This cat was playing this, and this cat was playing that.” So it felt like this kismet thing, where it all tied together. I said, “Cat’s got to be part of my identity.” He’s a cool cat. I love those cats. That kind of made me want to dive in, and then the story kind of came about.

BURSTYN: When you say the story came about, that’s a very glib phrase.

WOLFF: Well, I wasn’t working, nobody was hiring me during this time. I was 15, you know—

BURSTYN: You were 15?

WOLFF: I was 15, I was my ugliest version of myself. Not just physically, but also emotionally. I felt like it was just ugly, but it was a transitional time for me.

BURSTYN: Can you describe your ugliness?

WOLFF: Yeah. One, I was ugly. I had acne, nothing seemed to fit with my face. It’s weird, puberty, because it felt like certain things had grown and certain things hadn’t. Like my nose was sticking out a certain way, my one ear was bigger than the other, my curly hair was too much to handle. It was just a lot. I was going through a feeling that I didn’t belong anywhere. I couldn’t figure out what I was. Hyper and filled with so much energy and so much rage. I felt like I was a concert pianist without somewhere to perform. What do I do with all these emotions? I was overwhelmed, and at the same time I started to feel more inclusion and joy than ever with a group of friends in high school. I was really bullied in lower school and very left out in middle school. When I got to high school, my friends were taking me around the city. It was a kind of awakening as a person in tandem with this growing rage and disgust. I guess that mixture of someone who is finally feeling accepted, and feeling very fragile and vulnerable and open, and wrestling with this underbelly of rage and explosive loneliness. I would come home, I would write. Instead of studying for finals in school or doing homework, I would write this script. It was my form of therapy.

BURSTYN: So you got good marks in school?

WOLFF: I actually did. But when I was writing this script, I definitely was a B, C student. I was much more interested in writing. As I got into senior year of high school, I ended up with high honors, one of the highest averages in my grade.

BURSTYN: In New York?

WOLFF: The Professional Children’s School in New York. I actually shot Cat in the Moon in my high school. So that’s nice. The way I made Cat and the Moon was I just lived in a fantasy world where I bullied everybody until it happened.

BURSTYN: But you see, the good part about that was you were the writer, and you were the director, and you were the actor, and you weren’t dealing with other people who had other ideas of it going in another direction.

WOLFF: The Exorcist feels like the loosest, most free performance I’ve ever seen on film, so I guess my question is … I sometimes feel like I have to fight to defend the art of acting or something on set in my own way—not necessarily fighting people, but I have to convince. Acting is seen as sometimes, “Go do your acting thing.” Do you ever feel like you have to defend your space as an actor? That people don’t respect the art of acting on sets.

BURSTYN: Not around me.

WOLFF: That’s good.

BURSTYN: I’ve earned my place, and I’m treated very respectfully and I appreciate that. I’m allowed to do what I do best. People don’t interfere with that. Once you’ve proven yourself, once you have a lineup of statues, then you’re allowed to do what you do.

WOLFF: I was curious what you thought about The Cat and the Moon, because you were so nice about it. You said it was divine, and that meant a lot to me.

BURSTYN: It’s wonderful. Just wonderful.

WOLFF: Thank you.

BURSTYN: You know, I came with my friend, the composer Andre Fratto, and he was so impressed that you played jazz. Because he does film scores and he said, “So often people will say, ‘And we want the music to be the music kids are listening to. The fact that he had jazz in his film, that was an artistic choice. It wasn’t trying to outsmart—’how do we get the kids into the theater, lure them in with the right kind of music, whatever the hell that is.'”

WOLFF: We can smell it when they do that.

BURSTYN: Of course. The choice of jazz was so original. Jazz sounded new again, because you don’t hear it so much anymore. To me, it’s like an old love song.

WOLFF: Me too. Taxi Driver‘s all jazz music.

BURSTYN: Your film. I was just really impressed with the whole thing. It had a sense of reality about it, which is what we’re always reaching for, and I know you are compared to Cassavetes, but the comparison is the level of reality.

WOLFF: That’s so sweet. I love Cassavetes. I love A Woman Under the Influence. I love Husbands. He’s amazing. It’s funny, because he wasn’t one of the main people I was thinking of when I was making the movie. There are these directors named the Dardenne brothers, which, if you haven’t seen their movies, you should see them. I love them. I was thinking a lot of young Scorsese. A lot of Bergman. It was really interesting that people were struck by my similarity to Cassavetes. I think that if there’s a drawn comparison, it’s that he let his actors just breathe, and that’s all I wanted. I literally said to the cast, “If you want to start talking about something that has nothing to do with the scene, and that’s your feeling in the moment, I’d rather you do that than come in with little boxed-in bullshit. Little fake worked out stuff in your room.”

BURSTYN: So how much of it that’s on screen was scripted, and how much was improv?

WOLFF: Maybe 50%. No, maybe a little more. Maybe 60to 75% was on paper, because a lot of times it would be, blah, blah, blah, and then it would get back to the material somehow. Both wild and free. Somehow it would hone back into the material, so then the words would feel free.

BURSTYN: That’s what I thought it was. Did you rehearse?

WOLFF: Yeah, we did rehearse.

BURSTYN: How much?

WOLFF: Only about a week.

BURSTYN: A week before? The whole thing?

WOLFF: Yeah. The whole thing. Mostly with the kids.

BURSTYN: Did you rehearse in the sets?

WOLFF: On set, yeah we did. That was a lot.

BURSTYN: That’s great. That’s what we did in the ’70s always. Two weeks usually. Last Picture Show, we were there in Texas. We were rehearsing on the sets where we later shot. Exorcist we rehearsed for two weeks. King of Marvin Gardens we rehearsed. All of them. Because that was what you did. You didn’t just put people on, get in bed.

WOLFF: When you’re not working, how do you not feel like an imposter? Let’s say you didn’t have an Oscar, let’s say you weren’t Ellen Burstyn, because sometimes when I’m not working I feel like, “What am I doing? I’m an actor, but what’s my evidence?” So I go to an acting class, or something like that. But how do you get over the initial feeling of “I’m worthless” during those times when you’re not doing something that matters to you?

BURSTYN: Do you think a concert pianist only plays the piano when he has a concert? He practices, right? That’s why I go to the Actors Studio. That’s why I encourage actors to go to there. We provide a stage, an audience, commentary, and you do whatever you want. If I’m not working on a role, I’ll go do “Lady Macbeth” at the Actors Studio. A scene, the speech. Or if I’m preparing for a role, I’ll do an exercise. For instance, when I was going to do 33 Variations, she has ALS, physical deterioration throughout the play. So I worked on that where it started in her body. Where was the next place? Where did it go and how did it deteriorate? Then I just went in and did a poem for each stage.

WOLFF: Wow. What poems?

BURSTYN: Oh, a variety of poems. Mary Oliver, a lot. Do you know Mary Oliver?

WOLFF: Yeah, of course.

BURSTYN: I love her.

WOLFF: Amazing. We studied her.

BURSTYN: Where?

WOLFF: In high school. We read Mary Oliver. We read a lot of Hart Crane. I was always a big poetry guy, so I love Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson. And Yeats. Those are the people that I was always into.

BURSTYN: I love that poem of Mary Oliver’s, “When Death Comes.” You know that one?

WOLFF: Yeah, we read that—

BURSTYN: The last line is, “That when it comes, I don’t want simply to have visited this world.” And I feel that I haven’t simply visited this world. Like, when you tell me how I affected you on stage? I mean, when we were working together? That makes my life meaningful. That means that I didn’t just visit this world. I actually gave something. I affected you. I helped you in some way. I was of service to you. So my life has meaning because of that. I feel that same way with the actors of the Actors Studio, who are so generous in telling me how they’ve been helped. That makes me okay with all the mistakes I made. That I’ve been helpful. That’s important to know.

WOLFF: Well, you’re not dead yet. Jeez.