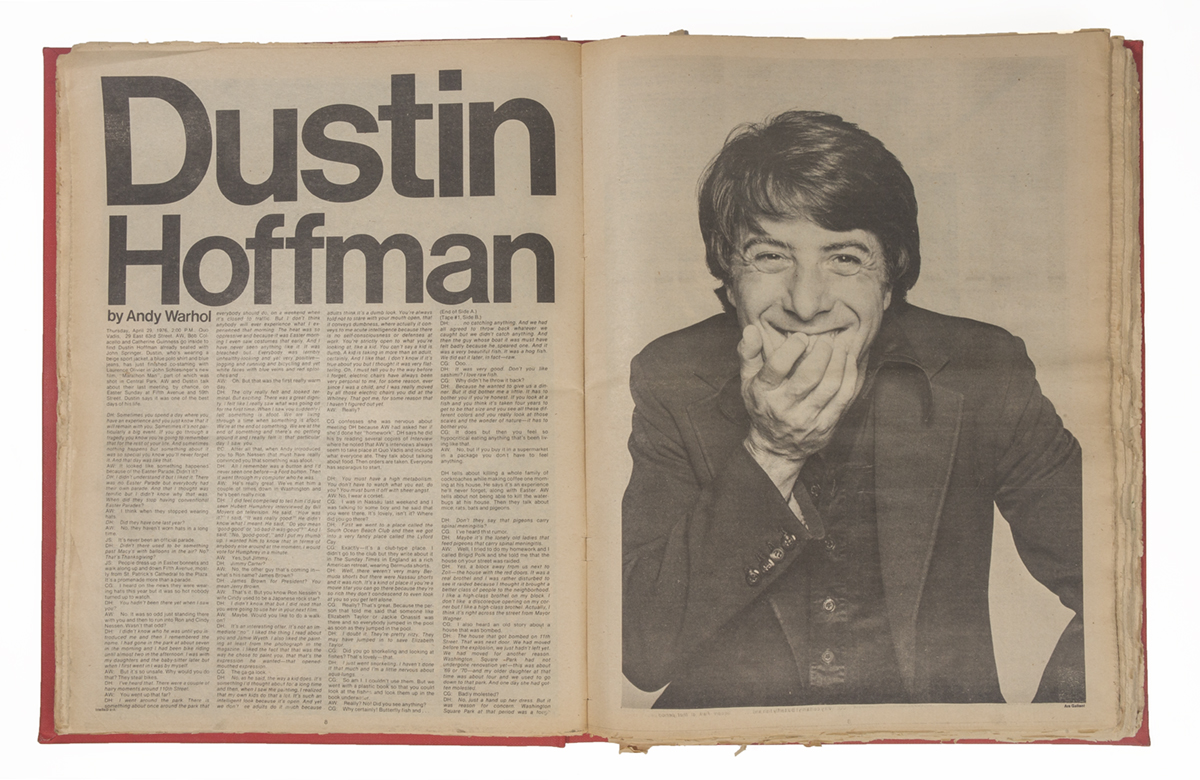

Dustin Hoffman Has The Best Day of His Life With Andy Warhol

This story is part of a collection celebrating the best—and wildest—Warhol conversations from the Interview archives.

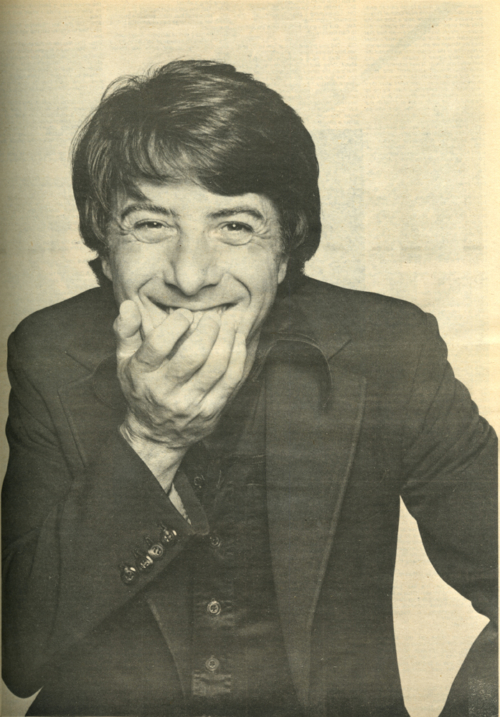

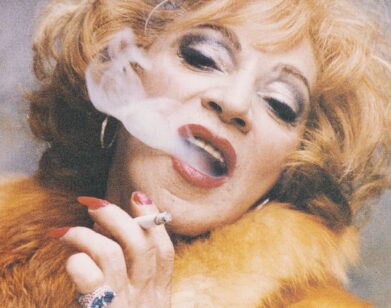

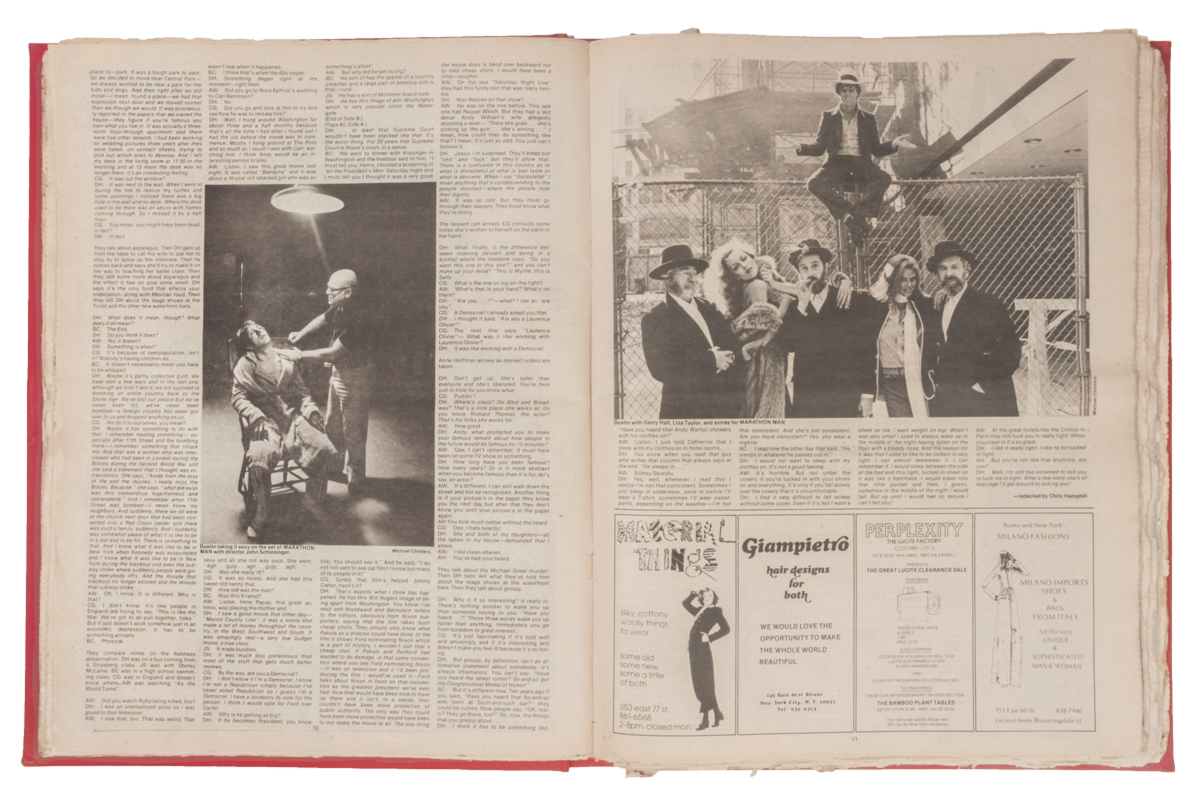

Thursday, April 29, 1976, 2:00PM, Quo Vadis, 29 East 63rd Street. Andy Warhol, Bob Colacello, and Catherine Guinness go inside to find Dustin Hoffman already seated with John Springer. Hoffman, who’s wearing a beige sport jacket, a blue polo shirt and blue jeans, has just finished co-starring with Laurence Olivier in John Schlesinger’s new film, Marathon Man, part of which was shot in Central Park. Warhol and Hoffman talk about their last meeting, by chance, Easter Sunday at Fifth Avenue and 59th Street. Hoffman says it was one of the best days of his life.

–––

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Sometimes you spend a day where you have an experience and you just know it will remain with you. Sometimes it’s not particularly a big event. If you go through a tragedy you know you’re going to remember that for the rest of your life. And sometimes nothing happens but something about it was so special you know you’ll never forget it. And that day was like that.

ANDY WARHOL: It looked like something happened because of the Easter Parade. Didn’t it?

HOFFMAN: I didn’t understand it but I liked it. There was no Easter Parade but everybody had their own parade. And that I thought was terrific but I didn’t know why that was. When did they stop having conventional Easter Parades?

WARHOL: I think when they stopped wearing hats.

HOFFMAN: Did they have one last year?

WARHOL: No, they haven’t worn hats in a long time.

JOHN SPRINGER: It’s never been an official parade.

HOFFMAN: Didn’t there used to be something past Macy’s with balloons in the air? No? That’s Thanksgiving?

SPRINGER: People dress up in Easter bonnets and walk along up and down Fifth Avenue, mostly from St. Patrick’s Cathedral to the Plaza. It’s a promenade more than a parade.

CATHERINE GUINNESS: I heard on the news that they were wearing hats this year but it was so hot nobody turned up to watch.

HOFFMAN: You hadn’t been there yet when I saw you?

WARHOL: No. It was so odd just standing there with you and then to run into Ron and Cindy Nessen. Wasn’t that odd?

HOFFMAN: I didn’t know who he was until you introduced me and then I remembered the name. I had gone in the Park at about seven in the morning and I had been bike riding until almost two in the afternoon. I was with my daughters and the baby-sitter later but when I first went in I was by myself.

WARHOL: But it’s so unsafe. Why would you do that? They steal bikes.

HOFFMAN: I’ve heard that. There were a couple hairy moments around 110th Street.

WARHOL: You went up that far?

HOFFMAN: I went around the Park. There is something about going once around the park that everybody should do on a weekend when it’s closed to traffic. But I don’t think anybody will ever experience what I experienced that morning. The heat was so oppressive and because it was Easter morning I even saw costumes that early. And I have never seen anything like it. It was bleached out. Everybody was terribly unhealthy looking and yet very positive—jogging and running and bicycling and yet white faces with blue veins and red splotches and…

WARHOL: Oh. But that was the first really warm day.

HOFFMAN: The city really felt and looked terminal, but exciting. There was a great dignity. I felt like I really saw what was going on for the first time. When I saw you suddenly I felt something is afoot. We are living through a time when something is afoot. We’re at the end of something. We are at the end of something and there’s no getting around it and I really felt it that particular day I saw you.

BOB COLACELLO: After all that, when Andy introduced you to Ron Nessen that must have really convinced you that something was afoot.

HOFFMAN: All I remember was a button and I’d never seen one before—a Ford button. Then it went through my computer who he was.

WARHOL: He’s really great. We’ve met him a couple of times down in Washington and he’s been really nice.

HOFFMAN: I did feel compelled to tell him I’d just seen Hubert Humphrey interviewed by Bill Moyers on television. He said, “How was it?” I said, “It was really good.” He didn’t know what I meant. He said “Do you mean ‘good-good’ or ‘so-bad-it-was-good’?” And I said, “No, ‘good-good’,” and I put my thumb up. I wanted him to know that in terms of anybody else around at the moment, I would vote for Humphrey in a minute.

WARHOL: Yes, but Jimmy…

HOFFMAN: Jimmy Carter?

WARHOL: No, the other guy that’s coming in. What’s his name? James Brown?

HOFFMAN: James Brown for President? You mean Jerry Brown.

WARHOL: That’s it. But you know Ron Nessen’s wife Cindy used to be a Japanese rock star?

HOFFMAN: I didn’t know that but I did read that you were going to use her in your next film?

WARHOL: Maybe. Would you like to do a walk-on?

HOFFMAN: It’s an interesting offer. It’s not an immediate “no.” I liked the thing I read about you and Jamie Wyeth. I also liked the painting at least from the photograph in the magazine. I liked the fact that that was the way he chose to paint you, that that’s the expression he wanted—that open-mouthed expression.

GUINNESS: The ga-ga look.

HOFFMAN: No, as he said, the way a kid does. It’s something I’d thought about for a long time and then, when I saw the painting, I realized that my own kids do that a lot. It’s such an intelligent look because it’s open. And yet we don’t see adults do it much because adults think it’s a dumb look. You’re always told not to stare with your mouth open, that it conveys dumbness, where actually it conveys to me acute intelligence because there is no self-consciousness or defenses at work. You’re strictly open to what you’re looking at, like a kid. You can’t say a kid is dumb. A kid is taking in more than an adult, certainly. And I like that. I don’t know if it’s true about you but I thought I was very flattering. Oh, I must tell you by the way before I forget, electric chairs have always been very personal to me, for some reason, ever since I was a child, and I was really moved by all those electric chairs you did at the Whitney. That got me, for some reason that I haven’t figured out yet.

WARHOL: Really?

[Guiness confesses she was nervous about meeting Hoffman because Warhol had asked her if she’d done her “homework;” Hoffman says he did his by reading several copies of Interview where he noted that Warhol’s interviews always seem to take place at Quo Vadis and include what everyone ate. They talk about talking about food. Then orders are taken. Everyone has asparagus to start.]

HOFFMAN: You must have a high metabolism. You don’t have to watch what you eat, do you? You must burn it off with sheer angst.

WARHOL: No, I wear a corset.

GUINNESS: I was in Nassau last weekend and I was talking to some boy and he said you were there. It’s lovely, isn’t it? Where did you go there?

HOFFMAN: First we went to a place called the South Ocean Beach Club and then we got into a very fancy place called the Lyford Cay.

GUINNESS: Exactly. It’s a club-type place. I didn’t go to the club but they write about it in The Sunday Times in England as a rich American retreat, wearing Bermuda shorts.

HOFFMAN: Well, there weren’t very many Bermuda shorts but there were Nassau shorts and it was rich. It’s a kind of place if you’re a movie star you can go there because they’re so rich they don’t condescend to even look at you so you get left alone.

GUINNESS: Really? That’s great. Because the person that told me said that someone like Elizabeth Taylor or Jackie Onassis was there and so everybody jumped in the pool as soon as they jumped into the pool.

HOFFMAN: I doubt it. They’re pretty ritzy. They may have jumped in to save Elizabeth Taylor.

GUINNESS: Did you go snorkeling and look at fishes? That’s lovely.

HOFFMAN: I just went snorkeling. I haven’t done it that much and I’m a little nervous about aqua-lungs.

GUINNESS: So am I. I couldn’t use them. But we went with a plastic book so that you could look at the fishes and look them up in the book underwater.

WARHOL: Really? No! Did you see anything?

GUINNESS: Why, certainly! Butterfly fish and…

[End of Side A. Tape #1, Side B.]

HOFFMAN: …no catching anything. And we had all agreed to throw back whatever we caught, but we didn’t catch anything. And then the guy whose boat it was must have felt badly because he speared one. And it was a very beautiful fish. It was a hog fish. We did eat it later, in fact. Raw.

GUINNESS: Ooo…

HOFFMAN: It was very good. Don’t you like sashimi? I love raw fish.

GUINNESS: Why didn’t he throw it back?

HOFFMAN: Because he wanted to give us a dinner. But it did bother me a little. It has to bother you if you’re honest. If you look at a fish and you think it’s taken four years to get to be that size and you see all these different colors and you really look at those scales and the world of nature—it has to bother you.

GUINNESS: It does but then you feel so hypocritical eating anything that’s been living like that.

WARHOL: No, but if you buy it in a supermarket in a package you don’t have to feel anything.

[Hoffman tells about killing a whole family of cockroaches while making coffee one morning at his house. He says it’s an experience he’ll never forget, along with Easter. Warhol tells about not being able to kill the water-bugs at his house. Then they talk about mice, rats, bats, and pigeons.]

HOFFMAN: Don’t they say that pigeons carry spinal meningitis?

GUINNESS: I’ve heard that rumor.

HOFFMAN: Maybe it’s the lonely old ladies that feed the pigeons that carry spinal meningitis.

WARHOL: Well, I tried to do my homework and I called Brigid Polk and she told me that the house on your street was raided.

HOFFMAN: Yes, a block away from us next to Zoli, the house with the red doors. It was a real brothel and I was rather disturbed to see it raided because I thought it brought a better class of people to the neighborhood. I like a high-class brothel on my block. I don’t like a discotheque opening on my corner but I like a high-class brothel. Actually, I think it’s right across the street from Mayor Wagner.

GUINNESS: I also heard an old story about a house that was bombed.

HOFFMAN: The house that got bombed on 11th Street, that was next door. We had moved before the explosion; we just hadn’t left yet. We had moved for another reason. Washington Square Park had not undergone renovation yet—this was about ’69 or ’70—and my older daughter at that time was about four and we used to go down to that park. And one day she had gotten molested.

GUINNESS: Badly molested?

HOFFMAN: No, just a hand up her dress. But it was reason for concern. Washington Square Park at that period was a tough park, so we decided to move near Central Park. We always wanted to be near a park for the kids and dogs. And then right after we found a place, we had that explosion next door and we moved sooner than we thought we would. It was erroneously reported in the papers that we owned the house—they figure if you’re famous, you own what we live in. It was actually a three-room floor-through apartment and there were five other tenants. I had been working on wedding pictures three years after they were taken, on contact sheets, trying to pick out which ones to develop. And I left my desk in the living room at 11:30 in the morning and at 12 noon the desk was no longer there. It’s an interesting feeling.

GUINNESS: It was out the window?

HOFFMAN: It was next to the wall. When I went in during the fire to rescue my turtles and some paintings I noticed there was a big hole in the wall and no desk. Where the desk used to be there was an abyss with flames coming through. So I missed it by a half hour.

GUINNESS: You mean, you might have been dead, in fact?

HOFFMAN: In fact.

[They talk about asparagus. Then Hoffman gets up from the table to call his wife to ask her to stop by and to spice up the interview. Then he comes back and says she’ll try to make it on her way to teaching her ballet class. Then they talk some more about asparagus and the effect it has on your urine smell. Hoffman says it’s the only food that effects your elimination, along with Mexican food. Then they tell Hoffman about the stage shows at the Toilet and the other new waterfront bars.]

HOFFMAN: What does it mean, though? What does it all mean?

COLACELLO: The End.

HOFFMAN: Do you think it does?

WARHOL: No, it doesn’t.

HOFFMAN: Something is afoot?

GUINNESS: It’s because of overpopulation, isn’t it? Nobody’s having children so…

COLACELLO: It doesn’t necessarily mean you have to be whipped.

HOFFMAN: Maybe it’s partly collective guilt. We have won a few wars and in the last one, although we didn’t win it, we did succeed in bombing an entire country back to the Stone Age. We’ve lost our people but we’ve never been hit, we’ve never been bombed—a foreign country has never got over to us and dropped anything on us.

GUINNESS: We do it to ourselves, you mean?

HOFFMAN: Maybe it has something to do with that. I remember reading something, especially after 11th Street and the bombing there, that struck me. And that was a woman who was interviewed who had been in London during the Blitzes during the Second World War and she said a statement that I thought was extraordinary. She says, “Aside from the loss of life and the injuries, I really miss the Blitzes. Because,” she says, “what did exist was this tremendous togetherness and camaraderie.” And I remember when my 11th Street was bombed—I never knew my neighbors, and suddenly, there we all were at the church next door that had been converted into a Red Cross center and there was such a family. I suddenly was somewhat aware of what it is like to be in a war and to be hit. There is something to that. And I know what it was like to be in New York when Kennedy was assassinated and I know what it was like to be in New York during the blackout and even the subway strike where suddenly people were giving everybody lifts. And the minute that blackout no longer existed and the minute that subway strike…

WARHOL: Oh, I know. It is different. Why is that?

GUINNESS: I don’t know. It’s like people in England are trying to say, “This is like the War. We’ve got to all pull together, folks.'” But it just doesn’t work somehow just in an economic depression. It has to be something actually…

COLACELLO: Physical.

[They compare notes on the Kennedy assassination. Hoffman was on a bus coming from a Strasberg class. John Springer was with Shirley McLaine. Colacello was in a high school swimming class. Guinness was in England and doesn’t know where. Warhol was watching As the World Turns.]

WARHOL: Did you watch Ruby being killed, too?

HOFFMAN: I was an unemployed actor so I was glued to the television.

WARHOL: I saw that, too. That was weird. That wasn’t real when it happened.

COLACELLO: I think that’s when the ’60s began.

HOFFMAN: Something began right at the movement. Right then.

WARHOL: Did you go to Nora Ephron’s wedding to Carl Bernstein?

HOFFMAN: No.

GUINNESS: Did you go and look at him to try and see how he was to imitate him?

HOFFMAN: Well, I hung around Washington for about three and a half months because that’s all the time I had after. I found out I had the job before the movie was to commence. Mostly I hung around at The Post and as much as I could I was with Carl, watching him. I think Andy would be an interesting person to play.

WARHOL: Listen, I saw this great movie last night. It was called “Bambina” and it was a 16-year-old retarded girl who was so sexy and all she did was suck. She went “Agh… gulp… agh… gulp… agh…”

HOFFMAN: Was she really 16?

GUINNESS: It was so lovely. And she had this sweet old nanny that…

HOFFMAN: How old was the man?

COLACELLO: Was this X-rated?

WARHOL: Listen, Irene Papas, this great actress, was playing the mother and…

HOFFMAN: I saw a good movie that other day, Macon County Line. It was a movie that made a lot of money throughout the country, in the West, Southwest and South. It was amazingly real, a very low budget movie, a true story…

SPRINGER: It made bundles.

HOFFMAN: It was much less pretentious than most of the stuff that gets much better reviews.

GUINNESS: By the way, are you a Democrat?

HOFFMAN: I don’t know if I’m a Democrat. I know I’m not a Republican simply because I’ve never voted Republican so I guess I’m a Democrat. I have a tendency to vote for the person. I think I would vote for Ford over Carter.

WARHOL: Why is he getting so big?

HOFFMAN: If he becomes President, you know something’s afoot!

WARHOL: But why did he get so big?

COLACELLO: He sort of has the appeal of a country preacher and a large part of America still is that—rural.

SPRINGER: He has a sort of Mortimer Snerd-look.

HOFFMAN: He has this image of an anti-Washington, which is very popular since Watergate…

[End of Side B. Tape #2, Side A.]

HOFFMAN: … at least that Supreme Court wouldn’t have been stacked like that. It’s the worst thing. For 20 years that Supreme Court is Nixon’s court, in a sense.

COLACELLO: We went to dinner with Kissinger in Washington and the hostess said to him, “I must tell you, Henry, I hosted a screening of All the President’s Men Saturday night and I must tell you I thought it was a very good film. You should see it.” And he said “I do not not vant to see zat film! I know too many of ze people in it!”

GUINNESS: Surely that film’s helped Jimmy Carter, hasn’t it?

HOFFMAN: That’s exactly what I think has happened. He has this Will Rogers image of being apart from Washington. You know, I’ve read anti-Woodward and Bernstein letters to the editors, obviously from Nixon supporters, saying that the film takes such cheap shots. They should only know what Pakula as a director could have done. In the film it shows Ford nominating Nixon which is a part of history. I wouldn’t call that a cheap shot. If Pakula and Redford had wanted to do damage, in that same convention where you see Ford nominating Nixon—it was on the television and if I’d been producing the film I would’ve used it —Ford talks about Nixon in front on that convention as the greatest president we’ve ever had. Now that would have been nice to have up there and it isn’t. In a sense, they couldn’t have been more protective of public authority. The only way they could have been more protective would have been to not make the movie at all. The one thing the movie does is bend over backward not to take cheap shots. I would have been a little tougher.

WARHOL: On the last “Saturday Night Live” they had this funny skit that was really terrible.

HOFFMAN: Was Nessen on that show?

WARHOL: He was on the one before. This last one had Raquel Welch. But they had a skit about Andy William’s wife allegedly shooting a skier—”There she goes… she’s picking up the gun… she’s aiming…” I mean, how could they do something like that? I mean, it’s just so odd. You just can’t believe it.

HOFFMAN: Jesus. I’m surprised. They’ll bleep out “shit” and “fuck” but they’ll allow that. There is a confusion in this country as to what is distasteful or what is bad taste or what is obscene. When I say “distasteful” I mean anything that’s condescending to the people involved—where the people lose their dignity.

WARHOL: It was so odd. But they must go through their lawyers. They must know what they’re doing.

[The dessert cart arrives. Guinness consults some notes she’s written to herself on the palm of her hand.]

HOFFMAN: What, finally, is the difference between ordering a dessert and being in a brothel where the madame says, “Do you want this one or this one?” and you can’t make up your mind? “This is Myrtle, this is Sally…”

GUINNESS: What’s the one on top on the right?

WARHOL: What’s that in your hand? What’s on there?

HOFFMAN: “Are you…?” – what? I see an “are you.”

GUINNESS: A Democrat! I already asked you that.

HOFFMAN: I thought it said, “Are you a Laurence Olivier?”

GUINNESS: The next line says “Laurence Olivier.” What was it like working with Laurence Olivier?

HOFFMAN: It was like working with a Democrat.

[Anne Hoffman arrives as dessert orders are taken.]

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Don’t get up. She’s taller than everyone and she’s liberated. You’re here just in time for you know what.

GUINNESS: Puddin’!

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Where’s class? On 83rd and Broadway? That’s a nice place she works at. Do you know Richard Thomas, the actor? That’s his folks she works for.

WARHOL: How great.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Andy, what prompted you to make your famous remark about how people in the future would be famous for 15 minutes?

WARHOL: Gee, I can’t remember. It must have been one some TV show or something.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: How long have you been famous? How many years? Or is it more abstract when you become famous than it is for, let’s say, an actor?

WARHOL: It’s different. I can still walk down the street and not be recognized. Another thing is if your picture’s in the paper they know you the next day but after that they don’t know you until your picture’s in the paper again.

ANNE HOFFMAN: You look much better without the beard.

GUINNESS: Ooo, I hate beards!

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: She and both of my daughters—all the ladies in the house—demanded that I shave.

WARHOL: I like clean-shaven.

ANNE HOFFMAN: You’ve had your beard.

[They talk about the Michael Greer murder. Then Dustin tells Anne what they’ve told him about the stage shows at the waterfront bars. Then they talk about gossip.]

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Why is it so interesting? It really is. There’s nothing quicker to wake you up than someone saying to you, “Have you heard…?” Those three words wake you up faster than anything. Immediately you go from boredom to great interest.

GUINNESS: It’s just fascinating if it’s told well and amusingly and if it’s interesting and doesn’t make you feel ill because it’s so horrid.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: But gossip, by definition, isn’t an affirmative statement about somebody. It’s always inflammatory. You can’t say, “Have you heard the latest rumor? So-and-so got the Congressional Medal of Honor!”

COLACELLO: But it’s different now. Ten years ago if you said, “Have you heard that so-and-so was seen at such-and-such bar?” they could be ruined. Now people say, “Oh, really? They go there too?” So, now, the things that you gossip about…

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: I think it has to be something like, “Have you heard that Andy Warhol showers with his clothes on?”

WARHOL: Listen, I just told Catherine that I sleep with my clothes on in hotel rooms.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: You know when you read that guy who writes that column that always says at the end, “He sleeps in…”

WARHOL: Sidney Skolsky.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Yes, well, whenever I read that I realize I’m not that consistent. Sometimes I just sleep in underwear, once in awhile I’ll wear a T-shirt, sometimes I’ll wear sweatpants, depending on the weather. I’m not that consistent. And she’s not consistent. Are you more consistent? Yes, you wear a nightie.

COLACELLO: I read one the other day that said, “He sleeps in whatever he passes out in.”

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: I would not want to sleep with my clothes on. It’s not a good feeling.

WARHOL: It’s horrible. But not under the covers, if you’re tucked in with your shoes on and everything. It’s only if you fall asleep over the covers that it’s uncomfortable.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: I find it very difficult to fall asleep without some cover. Even if it’s hot I want a sheet on me. I want weight on top. When I was very small I used to always wake up in the middle of the night having fallen on the floor with a bloody nose. And the reason for it was that I used to like being tucked in very tight. I can almost remember it. I can remember it. I Would sleep between the side of the bed and this tight, tucked-in sheet so it was like a hammock. I would crawl into that little pocket and then, I guess, somehow in the middle of the night I would fall. But up until then I would feel so secure I can’t tell you!

WARHOL: At the great hotels like the Crillion in Paris they still tuck you in really tight. When you crawl in it’s so great.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: I like it really tight. I like to be tucked in tight.

ANNE HOFFMAN: But you’re not like that anymore, are you?

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Well, I’m still too ashamed to ask you to tuck me in tight. After a few more years of marriage I’ll get around to asking you!

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JUNE 1976 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

———

Read more stories from the Celebrating Warhol collection.