Maripol Revives Downtown 81, Her Love Letter to Basquiat and His New York City

Many love letters have been written to New York City. Some detail the marvelous magic that sprouts from Manhattan’s garbage-ridden streets, where dreams come true and city girls find love; others are less rose-tinted, detailing the sleazy crime that consumes the concrete jungle. And then, there’s Downtown 81. Born of the minds of New York icon Maripol and photographer Edo Bertoglio, and written by former Interview editor Glenn O’Brien, the film originally aimed to capture the bombed-out and burgeoning indie scene of New York City through the eyes of an aspiring and broke artiste, played by Jean-Michel Basquiat (before he himself became a global icon of the underground art world). “I thought we should do a movie about this place because there’s something crazy happening,” Maripol told me during our breakfast at Gemma, inside The Bowery Hotel—formerly a gas station where the last scene of the film was shot. “There’s no way this emergence of everything is going to last.” And she was right. The New York of the film is punk and magical, and bygone. What’s left is a resonant nostalgia that still manages to attract young souls to its gentrified (but still not garbage-free) streets.

Much like the city that bore it, Downtown 81′s journey has been a tumultuous one. Although it was first shot in 1980, “in the middle of the coldest fucking winter,” the film was left unfinished until about 1999. During those years, the film’s original dialogues were damaged and Basquiat died tragically of a heroin overdose. But Maripol, the film’s producer and a close friend of Jean-Michel, as she calls him, didn’t give up on her vision, casting poet Saul Williams to dub his voice. Now, the film has found its second life, thanks to the Metrograph. Nearly 40 years after its original production, the film has been digitally restored and is playing in 25 cities across the country—a dream come true for Maripol, who set out to finish the film in honor of Basquiat. “More people will know about Jean-Michel in a real and separate way than just his art,” Maripol told me, choking back tears. “It’s like grabbing a little diamond.” Downtown 81 is a fairytale homage to the New York that was, and never again will be—but more importantly, to the friendships that blossom amidst the concrete. Below, Maripol opens up about the arduous six-week long Downtown 81 shoot, her fondest memories from set, and her advice to New York’s youth: “Everything is not about fame and money … if you love yourself, you don’t need that shit.”

———

ERNEST MACIAS: I watched the film the other day, and I’m very interested in learning how the idea of this film came to be.

MARIPOL: So you watched it and you liked it?

MACIAS: I was very intrigued by it. I was shocked by it because it’s not a New York that I see and know, obviously, and because it all seems so casual. It’s a different New York, essentially.

MARIPOL: I came to New York with my boyfriend, Edo Bertoglio, in 1976 when still in school in France, and then I never left. We would go to the night club and we already knew the kids. I wrote the synopsis, very simple: an artist going at it alone in New York City, and that’s the movie. Glenn O’Brien was a great writer and close friend, and he was a writer for Interview, he wrote about music. Everything was really intriguing, you know? In those days, you had to love the camaraderie—you always had each other, it was the best.

MACIAS: A lot of collaboration happening. Seems like it happened organically.

MARIPOL: To tell you the truth, that’s how it started. Eventually, we got money to shoot it. We shot in the winter of 1980-81. We shot Jean-Michel playing the artist in New York. It was not easy because he would go out at night.

MACIAS: Is it true that you had to wake him up every morning?

MARIPOL: Yes, that was part of what I’d do. He was only 19; he actually turned 20 on the set.

MACIAS: I’m sure there are many things you remember from being on set, but are there any moments from those six weeks, that you think about constantly.

MARIPOL: It was our first film. I’m not saying it was easy, because to make a film in the 80s was rough. Jean-Michel would forget his lines and Glenn would have to repeat them. The memories that I have, I can’t say they are fun, because it was really hard. I was the art director, I dressed everyone in the film. I had double outfits for each scene because Jean-Michel would keep the outfits. His hair was growing a lot, so we would take pictures and then make sure that it was the same the week after.

MACIAS: That’s incredible.

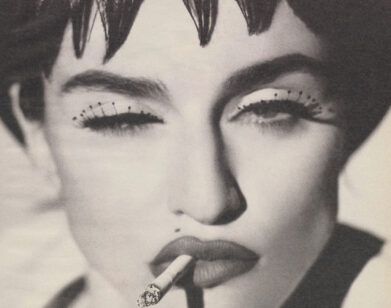

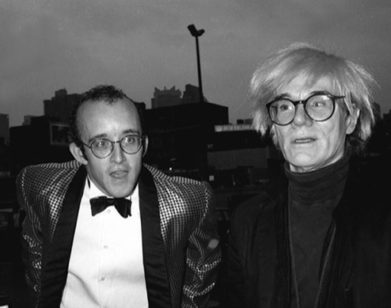

All polaroids taken by Maripol on the original set of Downtown 81.

MARIPOL: But there were a lot of tender moments. To be on set was everything, I just remember everything. It feels like yesterday. My fondest moment was dong the fashion show. I borrowed the sculpture we used from my artist friend Jo Shane.

MACIAS: That was one of my favorite parts of the film.

MARIPOL: It took a very long time to set everything up. I made a lot of those dresses with the same material: curtains. Of course we casted all the kids we already knew. It was cute.

MACIAS: Why bring the movie back to life right now?

MARIPOL: So let’s go back a little bit. The film shot in 1980, then it was canned, as you know. We were devastated—you work on something like this for six weeks and when it’s done, nothing happens. It was sad, but we moved on with time. Jean-Michel died in ’88. He lived a block away from me, on Grace Jones Street. He died in that building, that wall that you see, and the production of Downtown 81 was right across—I’m going to become emotional, I’m sorry. One day he said to me, “You know it would be so great if you finished that movie we did.” I said, “Jean, I don’t have any money.” That means it was important for him. The movie was this sort of airy story about him. A young artist trying to live and finding all this money, which happened right here—this used to be a gas station.

MACIAS: The scene where he finds the money and buys that car was shot right here? That’s crazy.

MARIPOL: Right here where we are. I slowly started the mental process, because it’s a mental process. At that point, I was not with Edo [Bertoglio], anymore. Little by little, I made calls to find the original lab because when you do a film you never have the original yourself. It stays in a temperature controlled room. I called all the labs in New York that could potentially have it. One day after Jean died in ’88, this guy called me up and said, “Yeah, I got some…” But I couldn’t have them because we needed a letter from the production company. I put it upon myself to finish the film. So it was more like I had to do that for him.

MACIAS: I saw that, originally, the movie was called New York Beat. How did it change to Downtown 81?

MARIPOL: That was Glenn’s change, and it was right. It made sense to call it that, it was accurate.

MACIAS: The film shows a New York that’s destroyed and beat-down. How much of that was 100% truth?

MARIPOL: Oh, there is no lie. You see the neighborhood was bombed out. Back then, the landlords—it was better for them to burn their building down because they would get the insurance, and they would wait. They knew that eventually it would be gentrified. Entire blocks were destroyed.

MACIAS: It’s all real. It’s all New York.

MARIPOL: We did not create anything, trust me. When the movie was finished, I knew that in order to have some sort of success, we needed to try to get into festivals. So I entered Berlin. The movie was a work in progress. It was not finished, so they didn’t take it. Then I entered both festivals of Cannes and Fortnight. One day I get a call from the assistant of the director of Fortnight: “We just want to know if the young kid inside the film is really the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat?” The next day they called again and said, “Congratulations.”

MACIAS: Why do you think the film was chosen then and not any sooner?

MARIPOL: It was very interesting. The movie was almost like a wine—was it a bad year? Was it a good year? They watch more than 300 films in one week. There were only three films chosen for the USA in 2000: Girl Fight, Shadow of the Vampire, and Downtown 81.

MACIAS: And how did you feel at that moment?

MARIPOL: Jean-Michel came in my dreams: I heard a beep–really, like a phone call, and he said “I’m the boyfriend of Beatrice.” I had it in my head all day long: “I’m the boyfriend of Beatrice.” I’m like, “Why was I called about? I’m so happy that the film is out.” I’m telling you something, which I’ve never told anyone because they’re going to think I’m crazy, but I really believe in spirits, and the call felt real. Jean-Michel really helped me, and I won’t even go into details, but I was so very sick I was going to die. I know that he helped me survive, and the film helped me survive.

MACIAS: That is beautiful.

MARIPOL: Then all day long hearing that voice, I realized Beatrice is the girl in the film, the model.

MACIAS: So it was Jean-Michel’s way of telling you he was happy about the movie.

MARIPOL: I know he was happy, so I was even more happy.

MACIAS: Everyone was happy then, and now the movie’s being re-released in 2019. For what purpose?

MARIPOL: You must have thought: “Why didn’t it do good in 2001?” But the movie was idolized. It did really great. My father passed away the day of the release. He was in France, it was really horrible. Then August happened, people go to the Hamptons. We were going to reprogram the film for September, and, well, September 11th happened.

MACIAS: That’s a lot to go through in one year.

MARIPOL: It was fate. Making an independent film is a lot of work, it’s kind of sad to see it standing in a drawer. It’s got to have a life again, and it is going to be in 25 cities now, it’s like a dream. It’s in America now, and more people will know about Jean-Michel in a real and separate way than just his art. Plus, it’s a great bit of film—I call it the gem. It’s like grabbing a little diamond.

MACIAS: Hopefully a lot of young people are going to watch—

MARIPOL: I don’t think it’s only young people.

MACIAS: True, but I want to get your thoughts on the youth who might not know much about that time. What would you hope that they take from this movie?

MARIPOL: I think the movie’s like a fairytale—and life is kind of a fairytale, isn’t it? Sometimes you have ups and sometimes you have downs. I think it gives you a look into becoming somebody big from something that happened to you. Jean-Michel was not famous when we did this movie. In a way, if you stick to your goal, and you get inspired—in this case, by the music—if you want to be an artist, you can make your mark.

MACIAS: You said earlier that during this time people were just helping each other out, and you were together, and that’s how the movie happened. Do you think that New York can be that way ever again?

MARIPOL: What do you think?

MACIAS: A lot of us come here chasing that spirit, but I don’t know if it’s entirely—

MARIPOL: Yes—if you have very close friends. I think we’re living in a more individual world, and unfortunately, it’s everybody for himself. Because back then, you didn’t need to have a lot of money to survive. You paid very cheap rent. You could always do one job a month and pursue your dream of being a director, writer, musician. That was enough to pay the rent and food.

MACIAS: If someone wanted to pursue and dedicate their life to art, it was easier than today.

MARIPOL: You think we functioned in nine-to-five jobs? We would go to the nightclub until 4 a.m., finish at Dave’s Corner, which was a little coffee shop, and then end up home with daylight.

MACIAS: Why is it important to remember that time in New York?

MARIPOL: Well, Edo [Bertoglio], said to me the other day, “You know, New York is like an old aunt that no one really wants to see.”

MACIAS: Were there any story lines or characters that were cut out that you wish would have stayed in the movie, during the editing process?

MARPIOL: Listen, honey, when you do a movie and it’s your first movie, and you don’t have that much money, you don’t really cut anything out.

MACIAS: The last thing that I want to talk to you about, and it’s because this scene really added the magic: when Jean-Michel meets Debbie Harry as a fairy godmother—that was wild. I did not expect the film to go there. Can you tell me about shooting that scene?

MARIPOL: We shot that scene in a building on 18th Street, the light was beautiful. I think Glenn believed in magic. People laugh when they see that scene—you have to be a bit naive to believe this. It’s a sad, but happy story. Jean-Michel was, subconsciously, extremely ambitious. He wanted to be famous. He wanted to make it, and I’m sure he’s moving in his grave because he’s not gaining all the millions that his paintings go for. Maybe that’s something that kids should be really aware of. Everything is not about fame and money. You got to take care of yourself. Love yourself, find your voice, and stay strong—if you love yourself, you don’t need that shit.