CANNES

Director Tyler Taormina Is Bringing Sincerity Back to Indie Cinema

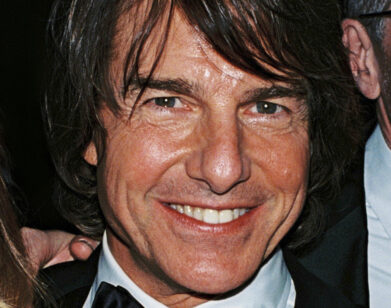

Every now and then, American independent cinema reinvents itself. The rollicking ‘90s gave way to the twee ‘00s, just as the gritty ‘10s of Sean Price Williams are beginning to make way for something new: a stylized, nostalgic and radically sentimental kind of filmmaking. In 2010, while still at Emerson college, Tyler Taormina formed the Omnes film collective and has since released three distinctive films: Ham on Rye (2019), the mid-length Happer’s Comet (2022) and now Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point, a work so unironic it at times feels avant garde. Alongside Ricky D’Ambrose and Jane Schoenbrun, Taormina is one of a small group of filmmakers whose embrace of sincerity is moving the needle in the independent scene. “I feel like we’re all really exploring, and taking another step forward,” the 33-year-old Taormina explained to me recently in a sun-dappled apartment overlooking the bustling Rue d’Antibes in Cannes, just days after Miller’s Point premiered to great acclaim and days before Eephus, directed by fellow Omnes member Carson Lund, would do the same. “I think that we’re seeing the beauty of modern cinema. All the greatest cineastes today are all involved in a very similar frontier of film, and we are coming at it in a very American way.”

Shot in a style somewhere between the ‘50s melodramas of Douglas Sirk and a Coke commercial, with a cast that features Sawyer Spielberg and Francesca Scorsese, Miller’s Point plays with nostalgia in strange, sometimes imperceptible ways. Set in Long Island around the turn of the millennium, the story gathers four generations of the Bolsano family around the Christmas table and serves up every festive cliche in the book: an after-dinner “walk” here, a bowlful of red and green M&Ms there, the tough guy brothers-in-law growing softer with each libation. We watch the family go through the annual motions before the film zeroes in on the younger generation as they break out into the night, running into the local cops (played by Michael Cera and Gregg Turkington), joining up with their peers at a late night deli, and pairing off under the snow. At the festival’s halfway point, Taormina joined me to talk about his unique approach to filmmaking, tempting the nepo-baby discourse, and almost casting Steve Guttenberg.

———

RORY O’CONNOR: How are you?

TYLER TAORMINA: I’m good. I’m a little tired.

O’CONNOR: Same, I hit that mid-Festival slump yesterday, but I’m managing. First time in Cannes?

TAORMINA: Well, I was here last year actually to visit, but under false documents.

O’CONNOR: Oh, yeah?

TAORMINA: Yeah. My old distributor gave me this pass.

O’CONNOR: Wow. That’s a cool pick.

TAORMINA: I was someone 25 years older than myself.

O’CONNOR: And it worked out?

TAORMINA: Yeah.

O’CONNOR: How was the screening? How did it feel to have a Christmas film in Directors’ Fortnight?

TAORMINA: It felt really strange. I find I’m too overwhelmed to actually watch the movie, so I didn’t really even watch it in my head. I truly get confused about what is happening, if people are actually enjoying it or not. Although from what I’m told, it went really well, and also an insane amount of people cried during the movie.

O’CONNOR: Yeah?

TAORMINA: It could have even been a majority…

O’CONNOR: Wow. Near the end, or—

TAORMINA: All different parts, but there’s some spots where the tears come out the most.

O’CONNOR: I mean, there is something about the way you give a point of view to so many different members of the family. You have this line about a “philosophy of no extras,” is that right? How would you explain that?

TAORMINA: Well, I like the idea that there are these gradients of ensemble casts where some, you learn about them more and then others, less so. I like these gradients to be sort of imperceptible. It gives the feeling that there is life everywhere, and you can learn so much about any person you look at. Whereas in most movies that would, maybe in a more perfunctory sense, utilize extras, or characters that we don’t really interface with in a meaningful way, you sense there’s no life there. This movie and all the other ones I’ve made are about a true desire to explore life all around us. I learned it from McCabe & Mrs. Miller, it’s Altman’s philosophy, and that makes that movie a beautiful study of that environment and that community.

O’CONNOR: Yeah. I felt it really adds to the mosaic feeling of the film. The way you use memory in it, almost like these little shards, like little micro observations that you’re putting together. I was wondering about your approach to memory in the film. I’m thinking about some of the small parts, like the aunt and uncle coming in with the VHS. There’s this shot of them kind of dancing as they come into the room, which looks like an image that someone would carry in their head from their family get-togethers. How do you go about arranging all this?

TAORMINA: It’s really all in the body. An idea that feels like you’ve experienced it, like deja vu, I wanted to capture that.

O’CONNOR: This quote came to mind when I was watching it. This is Umberto Eco, “Two clichés make us laugh. A hundred cliches move us. For we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, and celebrating a reunion.” I mean, that really slapped for me–

TAORMINA: That gives me shivers. What a brilliant mind who wrote that.

O’CONNOR: It really came to mind when I was thinking of this film. I mean, I wonder if that resonates with you? I mean, just in terms of Christmas itself, just the way that we go through these rituals…

TAORMINA: It’s like what we’re talking about with the extras, it’s really the same thing. Everybody is on this grand fabric, and then there is this intercommunication that creates enormous emotion. I mean, the codes and the steps that we all take together are such an important part of the emotions I was mining. It’s Žižek who talks about, if you don’t believe in the religion, but you go and do all the physical facets of the tradition of the mass or of a wedding. There’s so much preordained movement that engenders belief, and this is a very astute observation that I was aware of when making this movie.

O’CONNOR: You get a lot of references to Christmas films in there. The obvious one is the Jordan cutout from Home Alone, but you have it on a Roomba here. There’s a lot of things that felt subconscious or like little glimmers, and I was wondering if you were setting out to pay homage to any certain films in particular, or any style of filmmaking?

TAORMINA: Yeah. With Home Alone we were making a conscious allusion to it. My costume designer, Kim Odenthal was sort of riffing on that. I enjoy that so much because it really brings to light this internalized tradition. The same thing we were just talking about with the codes, is that we have also internalized this media from these earlier generations in the eighties and whatnots, or in All That Heaven Allows, which is another distinct and blatant reference point. It reminds me of the Leonard Cohen album, New Skin for the Old Ceremony. Here we are, doing the dance and the song, and soon we’ll be gone. I like how a postmodern approach could be thought of as new skin for an old ceremony.

O’CONNOR: I heard you use the line, “Like a layer of winter clothing that we keep on us.” There’s this aesthetic of advertisements that you’ve mixed in with the Sirk and Mannelli references as well. Could you talk a bit more about that? About this layer of winter clothing and how we subconsciously always have these references with us?

TAORMINA: Yeah, that’s something I’m trying to figure out too. It’s important to delineate that it’s not supposed to be subversive by way of satire, or criticism or polemic, but a lot of these movies are actually looking at these ensemble casts to explore a sense of identity. Emily is the perfect protagonist in this movie because her identity is a battleground in a sense. The way we talked about it, Matilda and I, was that each person she interacts with is not threatening her sense of identity, but almost taking it a little bit. Representation in media is profoundly moving to us, and these movies of the eighties, they really show us what life is, especially for teenagers. I come from kids’ television, mind you, and you write the kids’ shows so that the ages of the characters are actually a little older than the demographic. They’re trying to learn what the next step is. So much of our identity, and our sense of the world is taken from these movies, and that’s fascinating. And we live with that, it’s in us all the time, and yet we live a completely different reality than the one posited to us.

O’CONNOR: You said that your style is between sixties cinema and Nickelodeon shows?

TAORMINA: Yeah.

O’CONNOR: What were some of the Nickelodeon shows that would be a particular influence?

TAORMINA: There’s really two, which are Hey Arnold! and The Adventures of Pete & Pete. Those are the two influences that really stick out to me. I love the innocence, and the purity and the magic, and especially The Adventures of Pete & Pete is so cinematic. It’s Hal Hartley’s crew making those shows. They were hugely formative to me.

O’CONNOR: You mentioned not wanting to be subversive with references, or too postmodern and cynical about it. I was reading Jessica Kiang’s review in Variety, which put it better than I did: “Christmas Eve plays its traditions straight, with a sincerity and sentimentality so brazen, it borders on avant-garde.” I would go one further and say that it is avant-garde, the level of sincerity and sentimentality here.

TAORMINA: It almost makes me wonder, is that how we react to non-ironic sentimentality these days? [Laughs] To earnestness?

O’CONNOR: Yeah, exactly. But when everything is known in a sense, or you have all this information, earnestness can feel like a totally new thing. Are you conscious of the sincerity in the work?

TAORMINA: Well, I’d have to think of what it would mean not to be that way. One of the biggest engines of this film is my love of all these people. I have to. If I don’t love them, then it’s not going to be fun to make. And making a movie is so freaking hard. It’s so emotionally horrifying, but when I’m on set these brutal emotions are instantly erased when I see the beauty of these people. One of my first times being drunk, I had this weird thought that I wish I could hold all my memories in my hand, and this is way before I discovered cinema or filmmaking, and I think that’s what I’ve done.

O’CONNOR: Yes. How did the casting come about? I saw this interview between you and Michael Cera. I guess you guys go back a little while?

TAORMINA: Yeah, we started collaborating about five years ago. We wrote a script together that I hope will be his directorial debut. Anyway, he was very helpful in the casting process and cheerleading the film, and trying to connect us to people who I would never be able to get to myself. He’s a real soldier of cinema, but not only cinema, for poetry. It’s a true value of his. It’s an utmost priority for him, and I have so much respect for him, for that.

O’CONNOR: Did he put you in touch with Gregg Turkington?

TAORMINA: Yeah, and Ben Shankman too. There were a lot of people actually that agreed to be in the film, but it didn’t end up happening, because we pushed back the production by half a year. We lost some people like Steve Guttenberg.

O’CONNOR: No way?

TAORMINA: Yeah, and Michael Showalter and Tim Heidecker.

O’CONNOR: Wow.

TAORMINA: Parker Posey.

O’CONNOR: Wow. I mean, Posey and Guttenberg definitely would trigger this era. Was that in your thinking, to get names that were resonant of that era?

TAORMINA: Yeah. I’m very careful about bringing familiarity into the mix, because you have to really get the chemistry right or it could really fuck it up. For all these people, they had a very specific presence in the film. But Guttenberg would’ve been the perfect person in this film. I think I would’ve given him a really good role, and I think he thought so too.

O’CONNOR: I was also curious about how, obviously a lot of people when they saw Sawyer Spielberg and Francesca Scorsese, it seemed like maybe stunt casting, but after seeing it, it made sense to have those names there, because they’re resonant of that era of films.

TAORMINA: Well, I have to say two things. One is that Laura Robards is actually the granddaughter of Jason Robards. But the second thing is that I didn’t know that until we were rehearsing in her apartment. And the way that Sawyer and Francesca came into the mix was the same as anyone else. Everyone was found in this way of vetting the team, and the people close to us, even if they weren’t an actor. If they were then cool, let’s see them. But if they weren’t, sometimes even better, especially if you have an interesting cousin who’s 30, and vaguely Italian, or seems crazy. So it wasn’t intentional. But it was really interesting, this is a story about generational strife and disconnect, and I knew that these presences will be related to that in that way.

O’CONNOR: And the film’s kind of in conversation with cinema, in a way.

TAORMINA: Yes, of course. I feel like all the great directors are my aunts and uncles, and I feel just a crazy degree of self-flagellation to fulfill everything they’ve given us. Truly, I’m so grateful. Sometimes I just think, “I’m so, so, grateful for these people who made these great films.” That’s a huge part of it.

O’CONNOR: Were you wary at all that there might be some kind of nepo baby stuff thrown at it?

TAORMINA: I stand by the film in the sense that if you watch it, you see that these people are perfect for these roles. If you didn’t know who they were, you’d think the same.

O’CONNOR: I agree. So you set up Omnes [Films] with Carson Lund, your cinematographer here. It’s a film collective. Is there some kind of founding principle or aesthetic style? Or a manifesto of some kind?

TAORMINA: No manifesto. We’re not dogmatic, and we don’t really meddle in others’ creative ideas. If someone comes, we just respect what they do. The reason why it works so well is because we all so deeply admire each other’s ideas. There’s such a shared sensibility amongst us as best friends and people who grew up in very similar ways, and have ingested similar forms of art. I feel like we’re all really exploring, and taking another step forward, honestly. I think that we’re seeing the beauty of modern cinema and the conversation now. All the greatest cinemas today are all involved in a very similar frontier of film, and we are coming at it in a very American way that is specific to us.

O’CONNOR: Nice, and Carson Lund has shot all your stuff so far?

TAORMINA: No, he didn’t shoot Happer’s Comet, actually.

O’CONNOR: I’m curious about the interest in the night in both Happer’s Comet, and here.

TAORMINA: Yeah. There’s such a pregnant energy of the night, you know? I don’t know what it is.

O’CONNOR: This idea of sneaking out was-

TAORMINA: That was huge. I mean these memories of mine, sneaking out of my house as a kid and meeting up to hook up with my friends. Those are some fucking crazy memories that are just so epic. How the town could be transformed into the most magical place, just because we were experiencing it in that way for the first time. And how endless those nights felt. Time was so different then.

O’CONNOR: Yeah, for sure. You do give a good representation of that sense of time being shorter than… There’s the young guy with his group of friends, saying, “I wish everyone had friends like us.” Just that feeling that the world is smaller.

TAORMINA: Yeah, I know, and she says, “Well, we should all get married.”

O’CONNOR: Nobody could possibly have as good a friend on Christmas Eve, which is really sweet. I read that you’re working on another script with Eric, right now, a teen comedy?

TAORMINA: Yeah. It’s a farce comedy, sort of in the style of Blow-Up meets Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. It’s like a continuation or a John Hughes re-imagining. I’m really excited about it.

O’CONNOR: Okay. Well, I thank you. You’ve been very generous with your time.

TAORMINA: Thank you very much.