Dennis Hopper Part Two

This is part two of the Dennis Hopper interview, for the complete interview click here.

When Easy Rider came out in 1969, the times were changing for Dennis Hopper. Before writing, directing, and acting in his seminal road movie about a pair of cocaine dealers on a motorcycle trip across the fractured landscape of Vietnam War–era America, the talented but explosive Hopper—who broke out alongside James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955)—was still emerging from an involuntary Hollywood exile following his clash with the powerful director Henry Hathaway on the set of the 1958 western From Hell to Texas. But as the ’60s were staggering to an end amid a country divided by an unending war, the old studio system of moviemaking was crumbling. Easy Rider helped to emancipate American cinema from the tired Hollywood formulae, and the film’s iconic, psychedelic visions—the red-white-and-blue flag stitched onto the back of Peter Fonda’s black leather jacket might as well have been put there by Jasper Johns—served as the travel poster for the new, free-spirited American rebel. Hopper literally roared his way into the ’70s, courtesy of a Harley-Davidson chopper and a zeitgeisty movie tagline: “A man went looking for America. And couldn’t find it anywhere . . .”

With Easy Rider, Hopper not only evolved into a writer and director, but also a powerful character actor—a track on which he would continue throughout his career in such wide-ranging roles as the gentle drunk in Rumble Fish (1983), the mad bomber in Speed (1994), the art dealer Bruno Bischofberger in Basquiat (1996), the doomed father in True Romance (1993), but never so unforgettably as his cameo in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) as a raving photojournalist-cum-mystic, and the psychopathic nightmare incarnate Frank Booth in Blue Velvet (1986).

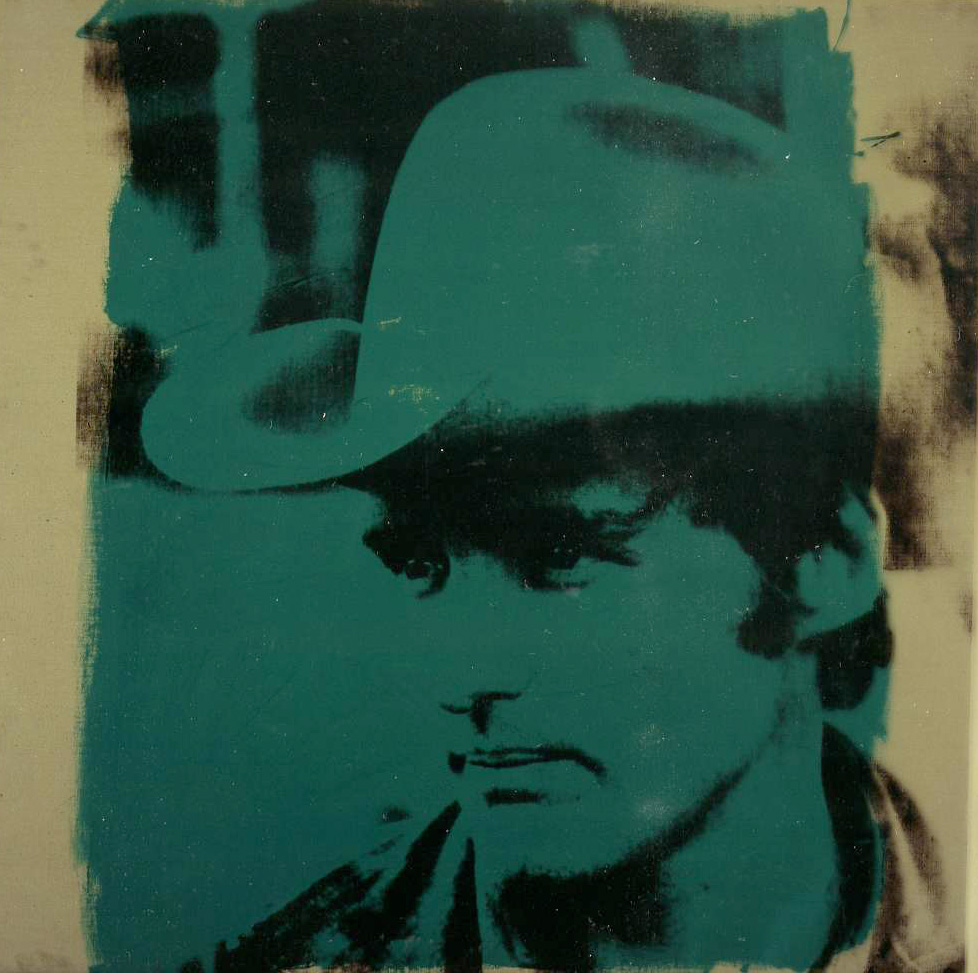

Hopper possessed so much intensity—on screen and off—that he protested it was difficult to successfully pursue more than one craft at a time. He claimed to suffer from an artistic schizophrenia—in one life, Hopper was an an actor, director, and screenwriter; in the other, a photographer, painter, and sculptor. At the time, serious movie actors did not pursue careers as serious artists and vice versa. But in the 1960s, while he was blacklisted across studio lots, Hopper took a lot of photographs, including many well-known portraits of his famous Hollywood friends, and immersed himself in the already-exploded L.A. art scene of that era—populated by artists like Ed Ruscha, Robert Irwin, and Wallace Berman—brought about by the opening of Walter Hopps, Robert Alexander, and Ed Kienholz’s famous Ferus gallery in 1957. Hopper bought an early Warhol soup can painting for $75, instigating a lifelong relationship with the artist and a passion for collecting.

After the critical and commercial success of Easy Rider, Hopper became a commodity in Hollywood again. He was riding high at the time, as was his drug and alcohol intake. He was bankrolled by Universal to make The Last Movie, his trippy movie about the making of a movie. The drug-addled on-set spectacle of the shoot in the Peruvian Andes was seized upon by journalists, and the movie was a financial disaster. Years later, Hopper was still consuming seemingly inhuman quantities of booze and drugs when he re-emerged on the Philippines set of Apocalypse Now. He continued to struggle with his substance abuse problems through Out of the Blue (1980) and Rumble Fish, both movies in which he portrayed an alcoholic father, until he got clean in 1986. Though he still managed to channel his unhinged, chemically altered side in performances, particularly his frightening turn in Blue Velvet and as the alcoholic basketball coach in Hoosiers (1986), a part for which he earned an Oscar nomination.

Throughout the many cycles of his career, Hopper has been incredibly high and unreachably low, lost and found, actor and artist, father and husband, hero and outcast, revered by one generation and misunderstood by another. But whatever he was at a point in time, Dennis Hopper lived the hell out of that moment. Shortly before his death last May after a long battle with prostate cancer, Hopper sat down with Interview chairman Peter M. Brant and gallerist Tony Shafrazi, who represents him as an artist. They did so at Shafrazi’s gallery in Chelsea, on the west side of Manhattan. Here we present part II of their interview—a celebration of his remarkable career and even more remarkable life.

It actually wound up taking me a year to edit Easy Rider because I was going cross-country as we were making it and couldn’t see the footage. But I came back with 80 hours of film.Dennis Hopper

TONY SHAFRAZI: So, Dennis, as we come to the end of the ’60s, with you having just recently returned to making movies after a period where you weren’t working in film as much, you come to make Easy Rider—which, of course, goes on to become a major classic. But as you were going to make the film, it was against the backdrop of a very interesting time in America. The Vietnam War is exploding—there are demonstrations everywhere. The Democratic National Convention is happening in Chicago, and William S. Burroughs, Terry Southern, and Jean Genet have all been sent there to cover it for Esquire—and this is all happening just as you’re conceiving the film. Originally, Southern was supposed to write Easy Rider, right?

DENNIS HOPPER: He didn’t write anything. Peter [Fonda] and I just talked out the story as we walked around on his tennis court in L.A. for about two-and-a-half weeks. I’d asked Peter and Terry to write it because I didn’t want to write a screenplay. But I had a total outline, and I knew where the scenes had to be and how long they had to be.

PETER M. BRANT: What was the total budget for Easy Rider?

HOPPER: Around $340,000. [Production manager] Paul Lewis and I were going cross-country to find locations, and I’d sent Peter to New York to work with Terry on the screenplay because [executive producer] Bert Schneider was saying, “I’ve got to have a screenplay! I’ve got to show the producers a document. You don’t understand. Just trust me!” So as Paul and I were scouting locations, we discovered that Peter got the date wrong for Mardi Gras: He was two months off. It was actually only two weeks away! Now, everybody who has tried to make a movie at Mardi Gras—including Orson Welles—has failed miserably. And as we’re getting further and further into figuring out the film, I’m turning more and more into Henry Hathaway. I’m worse than Henry Hathaway because I’ve waited so long to direct a movie like this. But then I discovered that we only have two weeks, so even though we didn’t have a go-project yet, we rushed and got a bunch of friends together and went to shoot it in New Orleans on 16mm. The whole acid trip and all of the New Orleans stuff was all shot on 16mm over four days. I shot the entire movie in four-and-a-half weeks. So that’s how it started. It actually wound up taking me a year to edit Easy Rider because I was going cross-country as we were making it and couldn’t see the footage. But I came back with 80 hours of film.

SHAFRAZI: So the Mardi Gras sequence was the first thing that was shot.

HOPPER: Yeah, and everybody left me before the part in the cemetery, except a cameraman, a sound man, Peter, and the girls. So I shot that whole thing, the whole acid trip. It was raining that day . . . It’s beautiful. So then I came back from that trip and it turns out that Peter and [associate producer and brother of Hopper’s first wife, Brooke Hayward] Bill Hayward are recording me. Every time I turn around they’re filming me—and I’m not sure why—but I’m saying things like, “We’re going to win Cannes, man! We’re young! We’re going to take our energy and our strength and we’re going to take this thing all the way! Just trust me and do what I’m saying! Nobody shoot any film until I tell them to!” I mean, we were all in open fights with one another at the time, I didn’t find this out until Bert called me into his office after the movie was released, but Peter and Bill apparently wanted to pay him back the money he’d given us for Easy Rider and fire me. This is Peter and my brother-in-law, okay? This is before we’ve written a screenplay. So apparently they went in to see Bert and made him listen to everything they’d recorded of me, and Bert listened to it and sounded really excited. He said, “All I’m asking you guys to do is bring a red light, a green light, and a blue light, so you can make white light. They’ll all mix together so you get color on the outside, but they’ll make white light in the middle. And then I want to use that in the cemetery sequence. You guys never bothered to do that?” So they said, “Well, we didn’t . . . You know, we think it was . . .” So Bert said, “Well, Hopper sounds really excited. He says he’s going to win Cannes. That sounds like a hell of an idea.” And then Bert said, “I’ve got to tell you one other thing: I hired Hopper to direct this movie, and he’s going to direct this movie.”

SHAFRAZI: Schneider said that?

HOPPER: Yeah. He didn’t tell me about it until after the film was done, but I knew we were having problems. Paul and I had gone off to find locations and places where the crew could live. When we got to New Orleans it was really dangerous because there were these marines who wanted to take me apart because I had long hair. You’d hear a lot of stories at that time of guys getting cut with razors and things. It was so bad that we skipped going to Texas. We went from New Mexico over to New Orleans, and when we got there—it had been two-and-a-half weeks or something—I called New York to see how Peter and Terry were doing on the screenplay. They hadn’t started writing it! I said, “But we’re shooting in a week-and-a-half!” So I got on a plane and went to New York. I went to Henry Fonda’s house, where Peter was staying, but he wasn’t there. I found them all having dinner with Rip Torn and a bunch of people at an Italian restaurant around a big Last Supper–kind of a table. I went up and said to Peter, “What the fuck is going on, man? Do you know how rough it is out there? We had to bypass Texas because of all these guys . . .” Rip said, “Terry and I are from Texas! I don’t like what you’re saying.” Anyway, we get in a big hassle. I later got sued and had to pay Rip $1 million for saying that I cut him out of the picture because he pulled a knife on me. But I hired a secretary and wrote the fucking thing in 10 days. It wasn’t a great screenplay, but I wrote it so they had a document. Terry never did anything. He broke his hip, so he couldn’t come on the shoot. He let me use his office. But later they all sued me. I paid them more money than I made on Easy Rider.

SHAFRAZI: How did Jack Nicholson get involved in Easy Rider?

HOPPER: Well, I had this guy, Jack Starrett, who became a director. He had played football in Texas, and was a really good actor. He was the guy I wanted. So Bert Schneider called me into his office. Bert never wanted to see anything until the first cut. That’s the way he worked—after he saw the first cut, he got involved. But he calls me into his office and says, “I haven’t asked you to do anything, but I want you to use Jack Nicholson.” I said, “But Nicholson is not right for the part. Starrett is.” He said, “Right or wrong, I want you to use Jack.” I said, “Okay, Bert, but you’re fucking up my movie!” [all laugh] You know? That was it! And then, of course, Jack was brilliant. Jack was great.

SHAFRAZI: And you had a great time doing the film.

HOPPER: Oh, wonderful. We had a great time on the shoot. I didn’t know this at the time, but Jack was also sent as a watchdog to see if I was okay. [laughs] I was into making the movie, man.

BRANT: You and Jack have stayed friends ever since.

HOPPER: Yeah, absolutely. Close friends. Old friends. I don’t see him very much. I don’t see anybody very much.

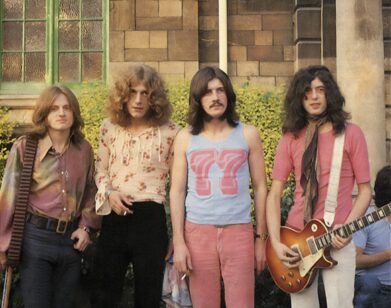

SHAFRAZI: One of the other interesting things about Easy Rider is the fact that about a decade before the advent of MTV and the music video, you did something radical with the music in the movie: The music in Easy Rider is not orchestra music. It’s not a score. It’s this music by bands and artists who were contemporary for the time. The music in Easy Rider is pop music—and you were one of the first filmmakers to use music in film in that way.

HOPPER: I think Easy Rider might have been the first time that someone made a film using found music instead of an orchestral score. No one had really used found music in a movie before, except to play on radios or when someone was singing in a scene. But I wanted Easy Rider to be kind of a time capsule for that period, so while I was editing the film I would listen to the radio. That’s where I got “Born to Be Wild” and “The Pusher” and all those songs. Orson Welles told me, “Don’t get confused. Use your best shots, and if the music works, it works, if not, then it doesn’t. But always cut to the image.” So I didn’t cut the film to the music—I cut it to the picture. But later, when I put “Born to be Wild” on there, it just worked, man.

BRANT: You know, Dennis, in looking at your entire career, there’s a kind of pattern that emerges. In a sense, it’s always these mistakes that lead to flourishing times.

HOPPER: Yeah.

BRANT: Which then lead, of course, to another mistake . . . [all laugh] And then to another flourishing time. But it seems like you’re always overcoming your mistakes and bouncing back better, wiser, and more creative. For example, during the period in the early-to-mid-1960s, after your blowup with Henry Hathaway on From Hell to Texas, when you weren’t making films, you were taking photographs. You stopped your film career and that led to another very creative moment in your life.

HOPPER: Which is unfortunate because then when I started making movies again, in the late ’60s, I stopped taking photographs. I don’t mix things. I’m doing one or the other.

The movies and the art world were two separate things before. The art world was way ahead of the movies—way ahead in terms of understanding our culture, the consumer reality of our society.Dennis Hopper

BRANT: The intensity you have is for one thing at a time.

HOPPER: Then I go back later and try to clean up the photos from the ’60s, and then Tony and I have our first show.

BRANT: There’s also a point, in the ’60s, where you’ve developed two very distinct aspects of your life. There is the film stuff, which we’ve been talking about, but then there’s also your involvement in the art world, which gets deeper and deeper. I know you forged a very close friendship with Dean Stockwell, who was one of the only actors to bridge those two worlds.

HOPPER: The art stuff was a whole other side of my life. Except for Dean, very few actors I knew were interested in art. As a matter of fact, I took Paul Newman to see Miles Davis and he didn’t get it. He was like, “What is this music?” These guys were very dedicated actors, brilliant people. But they were just sort of shut off from any kind of connection to the visual arts or music at that time. The first time I saw Dean Stockwell, after Jimmy Dean died, he looked like Jimmy—he was driving the same kind of Porsche that Jimmy drove, wearing the same kinds of clothes. The first time I saw Dean Stockwell at a restaurant I said, “Who the fuck is that?” And once somebody told me, I knew that Dean Stockwell had been a star.

BRANT: Dean Stockwell was a child actor, right?

HOPPER: Yeah. Dean had also been in Kansas City because his father was from there. I used to see him and Elizabeth Taylor coming out of school together and I’d say, “That lucky fuck.” [laughs] Dean played gin rummy with [artist] Wallace Berman, so we got to know each other through him and that whole group around [museum director and curator] Walter Hopps. And, you know, I’d been involved with the art people since the mid-’50s. I’d even done those experimental films with Andy [Warhol].

SHAFRAZI: Yes, the screen-test film, The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys, and Tarzan and Jane Regained . . . Sort Of [both 1964], in which you appear with Taylor Mead.

HOPPER: But it was a whole other side of my life that I couldn’t really share with the movie people, so I had a schizophrenic situation going on. We’d all smoke grass, but we weren’t doing any of the heavy stuff. The movies and the art world were two separate things before. The art world was way ahead of the movies—way ahead in terms of understanding our culture, the consumer reality of our society. The movie people didn’t collect art.

BRANT: And the art people don’t want to think that moviemaking is a departure, even though they say they like movies. They don’t like an artist doing movies. I mean, you’ve seen how people have reacted to artists who you’ve worked with on films, like Julian Schnabel or David Salle, doing movies.

HOPPER: Exactly.

BRANT: So it’s coming out of that period that you do Easy Rider, and it just takes your career to another level. And then, after Easy Rider—and following the pattern that we’ve identified as existing throughout your career—you go back and try to get The Last Movie [1971] made.

HOPPER: Which was a major mistake. [laughs]

BRANT: I met you with Andy in Los Angeles around that time, so I know how tough it was for you to put that film together.

SHAFRAZI: The Last Movie really is in concept much more experimental, almost underground, than some of the other films you’ve done. It’s about the making of a movie. It didn’t get the same reception in America, but in Europe, of course, it won a prize at the Venice Film Festival.

HOPPER: And it got me blacklisted.

SHAFRAZI: Really? Why?

HOPPER: Because I fucked with the most powerful man in Hollywood.

BRANT: Which was who?

HOPPER: Lew Wasserman, who Jules Stein handpicked to take over MCA. He was Ronald Reagan’s agent.

BRANT: Why did Wasserman blackball you?

HOPPER: Because he wanted me to re-edit The Last Movie after it won [best feature at] the Venice Film Festival, and I said, “I refuse.” So he said, “The only good artist is a dead artist.” Wasserman had this cane, which was George Washington’s cane at Valley Forge. But I wasn’t going to re-edit the film. How can you re-edit a movie that won at Venice? I don’t know. I didn’t know at the time. I’m still not sure how you do that. I’m not sure there was a movie there to re-edit.

BRANT: You also won something at Cannes.

HOPPER: Best new director. But, anyway, Wasserman shelved the movie. He said, “We’re going to play it for two weeks in New York, two weeks in Los Angeles, three days in San Francisco, and it will never see Europe. You’re out of here.” So before I left, I said, “By the way, Mr. Wasserman, how do you know that’s really George Washington’s cane? Could you explain that to me before I walk out of here?” He said, “No. Get the fuck out.” [laughs]

BRANT: Was that when you started working in Europe?

HOPPER: Well, I couldn’t work in Hollywood anymore. I used to resent the fact that all of these guys like Ernest Hemingway went to Europe. I always put them down. [laughs] But there I was, suddenly in France. I was trying to get some sort of a deal, but nothing worked out, and as that went on for a couple of years I got deeper into drinking. I had an agent named Edith Cottrell, who was also Wim Wenders’s agent. She said, “There’s somebody who’d like to meet you. He’s a young German director. Do you mind having dinner with him?” So I had dinner with Wim Wenders, and it was really nice. We had dinner about three times, and then he asked me to do The American Friend [1977]. He was going to use [John] Cassavetes, but he changed his mind. I’d made Tracks [1977] with Henry Jaglom, and Fred Roos, who was one of Francis Ford Coppola’s producers, had seen it. They were about to go do Apocalypse Now and Fred asked me to be in it. We had no script yet, but Fred said that Marlon Brando was going to be in it. So I said, “Well, if I have one line with Marlon . . .”

I came to play Colby, who was the C.I.A. guy who turns native. I was supposed to be the second in charge to Brando. I was in a nice, neat uniform with a hat and a medal. Coppola had brought in all these guys who were in Nam—special forces guys. They had us playing these incredible war games. Every night, for almost two months, we’d play these war games, which were intense. We had 250 native Flipinos who they’d brought down from the rice paddies to be my soldiers. They’d never been defeated by the Japanese—they’d never been defeated by anybody. They came down and built the village I moved into, where the temple was. So, anyway, I ended up looking more native.

SHAFRAZI: Is that how you wound up playing the photographer character?

HOPPER: Well, while we’re doing this, Marlon is on a million-dollar [per week] contract, and for a while he doesn’t show up. Finally he arrives, and there was this boxing match between two bantamweights in the Philippines. This is the first day that Marlon was there. So we go to the boxing match and then have dinner at Francis’s and, afterwards, we watch Seven Samurai [1954].

BRANT: By Akira Kurosawa.

HOPPER: Yeah. So then, at dinner, I have this little red book I’m studying, which detailed all of these covert operations that I’m trying to learn for the film, and I turned to Marlon and said, “Have you read Heart of Darkness?” I guess Francis had been on Marlon all day for having not read Heart of Darkness. So when I said that, Marlon completely flipped out. He said, “I don’t have to listen to this shit! Fuck you people!” And he leaves. So Francis goes after Marlon and it’s two weeks before they come back. Marlon was one of the great actors of our time, no question. However, he never cared about budgets except for what he was making, so he would stretch these things out as long as he could. You have to understand, there were 900 people on this crew. And we all waited for two weeks while Francis and Marlon went off in a riverboat. Finally they come back and Francis says to me, “We’ve read the book. We’ve decided that you’re going to be the character of this photojournalist who is sort of mad. He has all of these bags of cameras but he doesn’t really know how to use them.” So I said, “You’re talking about [P.D.] Ouspensky’s tarot card fool. Ouspensky wrote these tarot cards, but he never visualized them. The fool is the one who knows all of the secret wonders of the world but can’t remember where they are or how to use them.” That was the image that I used. So Francis and I would get together in the morning and write stuff down and we’d improvise off of it.

We had 250 native Filipinos who they’d brought down from the rice paddies to be my soldiers. . . . they came down and built the village i moved into, where the temple was. So, anyway, I ended up looking more native.Dennis Hopper

BRANT: Was the Rudyard Kipling chant all yours?

HOPPER: That was all me. It was from high school.

BRANT: “What are they going to say about him when he’s gone? That he’s a kind man? A wise man . . .” Was that all improvised?

HOPPER: Well, it’s hard for me to distinguish now what was Francis’s and what was mine, but a lot of it was mine. “Watch out for those heads . . .” [laughs] But Francis made a special canister for the film, because at that time I think you could only shoot for three minutes or five minutes at a time, and he wanted to be able to shoot for 10 minutes, so we could shoot for 10 minutes at a time. So we shot that scene [in which the photojournalist tells Willard about Kurtz] for at least a week—maybe a couple weeks. At the end, the last thing Francis says is, “We have done this scene 300 fucking times. Would you just do it once my way?” And I said, “Your fuckin’ way? I could’ve made Easy Rider five times with the fucking film you’ve lost here. What is your fuckin’ way?” [laughs] I had to play Gabby Hayes to his Roy Rodgers.

BRANT: At that point, Coppola was king of the world.

HOPPER: Oh, yeah. And he was a good friend.

BRANT: Of all of the great things that you’ve done, for me, this performance you give in Apocalypse Now is at or near the top. It really is a magical type of sequence that pours the entirety of what has happened to you as an actor, as a person, into a few minutes. It’s also a quintessential example of a performance that breaks from the discipline of the formal filmmaking that you were working under with Henry Hathaway. It’s a total break from that, but in breaking it becomes poetic. It’s one of the great performances in film.

HOPPER: Francis, in the end, was super.

SHAFRAZI: Certainly in that documentary on the making of Apocalypse [1991’s Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse] you can see Coppola preparing that scene. He announces on film that the scene he’s writing is the one with you as the boat arrives. Also, during the filming of the scene, it’s clear that Coppola is really fond of you. You can see a great camaraderie there, even though there is a challenging thing going on. Circumstances, I’m sure, were very tough.

HOPPER: We used real bodies a lot of the time, but Marlon didn’t know. Francis didn’t know. But I hung out with the prop guys because I knew those were the guys to hang out with. I’d been around movies for a while—they could get you anything. [laughs] They were storing them next to me in a freezer.

SHAFRAZI: A dead body?

HOPPER: Well, if you look at the film, when I get on the boat, that’s a real body there, brother. So when Martin [Sheen] went by at one point, after we’d been shooting for a while, he touched one and realized it was real, and he freaked out. So did the authorities and everyone else. We had a little bit of a problem there for a moment. [all laugh]

BRANT: So then, after the epic battle to make Apocalypse Now, you got together with Coppola again to do Rumble Fish.

SHAFRAZI: Which was wonderful. I think your performance in Rumble Fish is equally incredible to the one you gave in Apocalypse Now. The way you connect with Matt Dillon and Mickey Rourke, who play your sons in the film—the way you connect with them as a father—is magnificent.

HOPPER: Well, things had changed with Francis at that point. He had grown into what we called a Silver Fish. He was now in a trailer. You never saw him. He talks to you over a mic. During those scenes, Francis is never present. So you’re with Matt and Mickey, and it’s cool in a way. So I’d get to set and say, “What are you doing in there, Francis? Are you making spaghetti? Can you hear me?” But it was wonderful. Some of that was improvised, too. Not all of it, but the scene in the bar was. Francis had lost his studio, Zoetrope, so we got these milk trucks and drove all of the equipment out in the middle of the night and went down to Tulsa. So first he shot The Outsiders and then we shot Rumble Fish.

SHAFRAZI: After that you came back to New York. I remember seeing you with a movie that you had directed, Out of the Blue [1980].

HOPPER: When I went out to do Out of the Blue, it was initially only to act in the movie. Paul Lewis, who was my production manager—the producer on most of my movies—was producing it. What happened was that Out of the Blue was written by this husband-and-wife writer team, and the guy who was going to direct it had never made a real movie before. Paul Lewis wanted me to play the father of Linda Manz’s character. So I go to Vancouver to play this father character, and I’m sitting in my trailer ready to work for two-and-a-half weeks, and Paul keeps coming to me and saying, “This guy can’t direct, man. This is awful. There’s no usable footage.” He said, “You go in there.” So I said, “I’m not going to go in and fucking intimidate this guy. I’m going to stay here until he wants me to work.” So after two-and-a-half weeks, it’s a Friday, and Paul and I are having dinner and he said, “I’m closing down production.” So I said, “What? I haven’t even worked yet!” He said, “There’s no usable footage.” But, he said, “You could make it in three-and-a-half weeks. But we’ve got all of these locations. We can’t move them.” I said, “I’m going to move them all to the center of Vancouver.” So, it’s like, boom! I move all the locations, rewrite the whole thing, and shoot it all in three-and-a-half weeks. I do it and I get it into competition at Cannes, but Canada refused to put their flag behind it. Then they renounce it as a Dennis Hopper movie. Afterward, we tried to distribute it, but we couldn’t get it out for a wide distribution—it’s about incest, so no one wants to touch it. Now, I’m sitting in my house in Taos, New Mexico, going, “Man, this is it. I’m broke.” Then, suddenly, I started painting. I didn’t know what else to do. I’d painted before, but all of my earlier paintings were destroyed in the Bel Air fire in ’61. I tried to paint again after that, but I couldn’t do it. And then I started assembling objects with photographs, because at the time they wouldn’t let us show photographs with paintings. Back then, you couldn’t even show Man Rays with paintings.

BRANT: The year 1986 is a big one for you. It’s the year Blue Velvet came out. It’s the year you did Hoosiers. It’s the year where a number of things change for you.

HOPPER: It’s the year that I got sober—it’s the first year I was sober.

BRANT: So it’s a pivotal year in all these respects. How did you wind up playing Frank Booth in Blue Velvet? It’s an unforgettable performance, but also a very personal one. What was it like for you working clean for the first time in years?

HOPPER: It was a scary time. I’d used drugs for so long as an acting device. People would ask me about drugs and things and I used to joke and tell them, “Well, I’m really an alcoholic and I used drugs to cover it up.” Which, I’m afraid, was actually true. But once I got sober, I had no devices to use, so I really had to go back to the work I’d done with Lee Strasberg in order to not have to take a hit of coke or smoke a joint or have a drink in order to go do what I needed to do—so I could just go do it. Then, in the case of Frank Booth, I’m now playing this alcoholic without alcohol, a drug addict without drugs, because I was clean.

SHAFRAZI: How did you get the role in Blue Velvet? I heard that you called up the director, David Lynch.

HOPPER: I’d also done River’s Edge that same year [1986], which is also a really good movie. I never met David Lynch before. I just called him up. He was already in North Carolina shooting with Kyle MacLachlan, Laura Dern, and Isabella Rossellini. They were having lunch when I got him on the phone. I said, “David, I know we’ve never met, but you don’t have to worry about me playing Frank Booth, because I am Frank Booth.” So the story I heard is that David came back to the lunch table and said, “I just had a wonderful conversation with Dennis Hopper. He told me that he was Frank Booth. It’s going to be great for the movie, but I don’t know how we’ll ever have lunch with him.” [all laugh]

People would ask me about drugs and things and I used to joke and tell them, ‘Well, I’m really an alcoholic and I used drugs to cover it up.’Dennis Hopper

SHAFRAZI: What was it like that first day?

HOPPER: The first day on the set I meet Kyle MacLachlan and Isabella Rossellini, and David as well. Fred Caruso is producing. And the first scene we have to do is the heavy scene where Frank comes in, demands his bourbon, and does the whole thing with the rape. We’re doing the scene and Isabella exposes herself, which—whew, that was a shock, because she really did and nobody could see it but me. [laughs] Obviously she and David had worked that out. But it was a surprise to me. I don’t know whether it helped or hindered . . . [all laugh]

SHAFRAZI: What about the laughing gas?

HOPPER: David brought in this helium-only gas that made you sound like Donald Duck. I said, “David, you know, I thought of this as nitric oxide or amyl nitrate.” And he said, “What’s that?”

BRANT: [laughs] He had no idea.

HOPPER: David was like a Boy Scout. He doesn’t take drugs. He meditates. He’d give direction like, “Dennis, if you say that, when you say that word . . .” And I’d say, “David, that word is fuck.” He’d be like, “Yes, I know, and when you say that word . . .” He wouldn’t even say it. But he’d written this film . . . You know, you’d do this very, very dark scene, and he’d be like, “Howdy-doody! Solid gold! Let’s do one more!” It makes you think that whatever he has inside, he really keeps buried. [all laugh]

BRANT: So you went straight from doing Blue Velvet to playing a very different kind of character in the alcoholic basketball coach you play in Hoosiers.

HOPPER: I did Blue Velvet right before Hoosiers. I didn’t even go back to Los Angeles—I went straight to Indianapolis.

SHAFRAZI: You initially turned down Hoosiers.

HOPPER: I didn’t think it was right for me. I got nominated twice [that year] for the Golden Globe—once for Hoosiers and once for Blue Velvet—so I cancelled myself out. I got nominated for the Academy Award only for Hoosiers. On the morning they announced the Oscar nominations, they sent a camera crew to my house because they thought I would get nominated, but I thought I would get nominated for Blue Velvet. So they had the camera on me when they announced the nominations and I was like, “Hoosiers? Yeah, right, Hoosiers!” [all laugh] But it was a great experience. David Anspaugh, the director, he was good. In the beginning it was a role that I thought Harry Dean Stanton should’ve done. But Harry said, “Aren’t you from Kansas?” And I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Didn’t you have a hoop on your barn?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “I think you may be the guy that David Anspaugh’s looking for.”

BRANT: At that point you’d made it all the way back and you’ve worked regularly since then. You did Chattahoochee [1989] with Gary Oldman, The Indian Runner [1991] with Sean Penn, Speed, True Romance, you were in David Salle’s movie Search and Destroy [1995], you played Bruno Bischofberger in Julian Schnabel’s first film, Basquiat. In the last decade, you even got back into doing some TV with 24 and Crash. And you’ve consistently worked as an actor ever since.

HOPPER: The unfortunate thing was that, well, I got married, and I couldn’t turn anything down at one point because of financial needs. I think I did a lot of damage, very honestly, to my career because I never had the opportunity to say, “No, I don’t want to do that. I should wait for something else.” So I did a lot of crap. I used to tell people, “A lot of the films I’ve made you only see in Eastern Europe and Fiji.” They’re making pretty good movies in Eastern Europe right now, so I’ve got to change that line.

SHAFRAZI: You’ve also continued to work and grow as an artist.

HOPPER: Yeah, and that’s changed a lot, too. When I was starting out, the movie people really didn’t collect. As a matter of fact, if you even mentioned art, they used to show you the elevator. They want to know about a commercial venture. But now so many actors and directors and people in the movie business collect art and are involved in the art world, as you know, Tony. It’s very different than it was.

BRANT: You might not have touched so many nerves in pop culture if you didn’t do everything you’ve done. For example, being in the video game Grand Theft Auto, which my son was involved with. How many millions of people played that game? How important is something like that culturally?

HOPPER: That’s another thing that the agency tried to stop me from doing. They said, “You don’t want to do a video game at this point,” or “You don’t want to do commercials.” But, in my view, pop art opened everything up.

SHAFRAZI: The fact that you’ve viewed making movies and making art that way is a big reason why both you and your work have stood out.

HOPPER: Well, it has definitely led me to try a lot of things that I might not have tried otherwise, and to push myself, even when the work or my life in general wasn’t exactly where I wanted it to be. Even when I was doing movies where the material wasn’t great, I always tried to take shit and make gold out of it—and every once in a while, I’d hit a film that was like an undiscovered gem. I always tried to do the best job that I could.

Read the entire interview with Dennis Hopper here.