Austin Calling

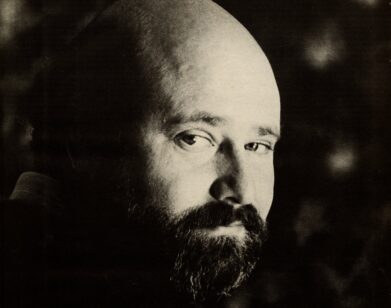

DAVID ROSENTHAL (LEFT) WITH ALESSANDRO NIVOLA AND ABIGAIL BRESLIN ON THE SET OF JANIE JONES.

Janie Jones, a film by David Rosenthal premiering today at Tribeca Film Festival, chronicles the emotional, musical and physical journey of a 13-year-old girl in tour busses and wood-paneled cars. Abandoned by her mother at a late-night rock show, Janie is pawned off on her father, Ethan: the dreadfully cool, crowd-surfing lead singer who has little desire to tack on the title of “father figure” to his hip façade. Janie follows the band, which unravels at the seams with her arrival, while her mother has disappeared and her father keeps sobriety at bay. Taking on anything but traditional roles, the two drive across the country in a pursuit of a gig at SXSW and, in the midst of everything, a relationship.

Janie Jones is as much musical journey as it is an emotional one: the music is weaved into the narrative like a hinge that forces the two seemingly unrelated characters together. Guitars are used as pawns for bail money, and duets become an instrument for survival in an increasingly hostile world. And, it turns out, director David Rosenthal is all too familiar with the depicted journeys.

ALICE GREENBERG: Why Janie Jones—are you a big Clash fan?

DAVID ROSENTHAL: Yeah, I’ve been a huge Clash fan. But it’s also one of those incidental titles that connects and loops around; it’s about this girl, Janie. When I was writing Eric’s character, and in my mind where he came from musically, he was sort of a proto-punk guy coming out of school and his first album was in that vein, and he was touring all around. And on his first tour he was connecting with his fans, who were people who were into punk music, and one of these girls was the woman who had his kid—and her last name was Jones, and she probably always wanted to name her daughter that.

GREENBERG: So this film is actually very personal to you, in many ways.

ROSENTHAL: Yeah, I met my daughter—I have a daughter; I’m 42 and I met her when I was 30 and she was 11, and she’s now 22. I sort of had a very brief fling with a woman who was a bit older than me, I was 18, and she wound up getting pregnant and calling me several months later and saying she wanted to do it on her own and didn’t want me to be involved at all. I was highly immature at the time and I didn’t engage with it and for a long time and I left it alone until it ate away at me; I struggled with it for years, and eventually I reached out to her and we figured out a way for me to be involved in my daughter’s life.

GREENBERG: Are there parallels between you and Ethan?

ROSENTHAL: Totally. I didn’t want to tell an autobiography of my life story because it’s too close and very personal, and too many feelings could be hurt, so I wanted it to be an analogue to my experience. In the movie, Ethan isn’t ready to accept that this girl is his daughter, so he’s in denial; and for me, that happened over a long period of time, and I wanted to set it in a much shorter time frame in the movie. I wanted it to exist in an analogous world with the one I lived. Independent filmmaking is just as unglamorous and egocentric as the songwriting world. Whether they’re good or mediocre, they’re almost always narcissistic, and I think this is true of directors and filmmakers, and with this I wanted in the film to create an alternative universe to my own experience.

GREENBERG: What inspired you to make a film out of your experience with your daughter?

ROSENTHAL: I think much later, when the experience washed over me more, it was one of the biggest events that changed my life, meeting my daughter for the first time. Before I reached out to her mom, she had told everyone she was artificially inseminated—and she kept up that story until I’d called her. And, you know, she got married and she had another kid, and so she had to unravel herself from that whole story. I came down to Arizona, where they were living, and went to my daughter’s school-and there’s a hallway and the bell rings and all these kids flood out, and I’m looking for my daughter, and she suddenly appears and looks at me and ran into my arms, without any denial or any resentment or anything. And it was a beautiful moment, and it’s hard to explain the first time you see your child that you’ve never met before, there’s a bizarre genetic, soul connection, whatever you want to call it, that’s so powerful, and I guess I wanted to share that and tell that story in some form.

GREENBERG: One of the very prevalent themes in the film is the role reversals that are very visible and dynamic throughout the journey. What did you want to convey by empowering Janie and disempowering her parents at times—but then flipping it entirely and projecting Janie as a very innocent, fragile child?

ROSENTHAL: For me, there is a constant role reversal between a parent and a child. I’ve experienced it in my life, and certainly with my daughter, who’s often wise before her years. I’ve personally experienced this role-shifting in my relationship, and seen it in others. Also, with Ethan, he’s a guy who’s so egocentric, and she saves him—they save each other, really—but she wakes him up from this dream about what his life is. And once he wakes up he can give to her, where before it was her who was constantly giving, and he really gives her the opportunity to be a child.

GREENBERG: How do the various instances of abandonment—by band members, family, or the world—interplay with each other in the film?

ROSENTHAL: I think this is such a common theme in family and relationships. I feel like we all talk about these issues and I feel like it’s universal—because we’re all abandoned in little ways. In the film, Ethan is abandoned by his father who kills himself and his mother who doesn’t care, and Janie is abandoned by her mother and she is totally abandoned by her father, and they’re all swimming in miasma of abandonment. So many people experience this, and it trickles down and from relationship to relationship and bleeds into other relations and forms other bonds, too.

GREENBERG: What went into your decision in attributing the two very different styles of songs to both Janie and her father, Eric?

ROSENTHAL: One of my closest friends, and someone I was romantically involved with while I was writing, was Gemma Hayes. She’s an incredible recording artist, so I knew I wanted her to write the songs for Janie, but I also knew that the voice had to be musically different from Ethan’s. So I searched high and low and was turned onto Eef Barzelay, and he was perfect. We were very conscious of writing songs that on Janie’s side were not too sophisticated but emotional, and Eef writes these very interesting and soul-baring songs; and Eef and I were very conscious of wanting to create songs for Ethan’s band that were very average, not so special, and show that Ethan had come to a place musically at his career that was kind of a dead end creatively.

GREENBERG: It’s very striking throughout the movie that Eric isn’t scared to corrupt his daughter. He’s a very cool dad. Have you always imagined his character like this?

ROSENTHAL: Yeah, I have, I mean I’ve observed it a lot. I know a lot of musicians and I’ve observed some older ones [laughs] that hang with their kids. And they are really not hung up – without judgment or anything—they’re just not hung up by certain things. And it allows a certain freedom, a friendship that I’ve observed. It’s not a typical hierarchy of a family. It becomes more like these two characters save each other, they become best friends, and that’s my experience with my daughter; it’s not a typical relationship, and it didn’t evolve in a typical way, but in the end it becomes beautiful.

GREENBERG: Is your daughter coming to the premiere?

ROSENTHAL: She is. My family also came to the premiere at the Toronto Film Festival, and my daughter was there, and I dedicated the move to her.

JANIE JONES PREMIERES TODAY AT THE TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL. FOR MORE ON THE MOVIE, VISIT THE FESTIVAL’S WEBSITE.