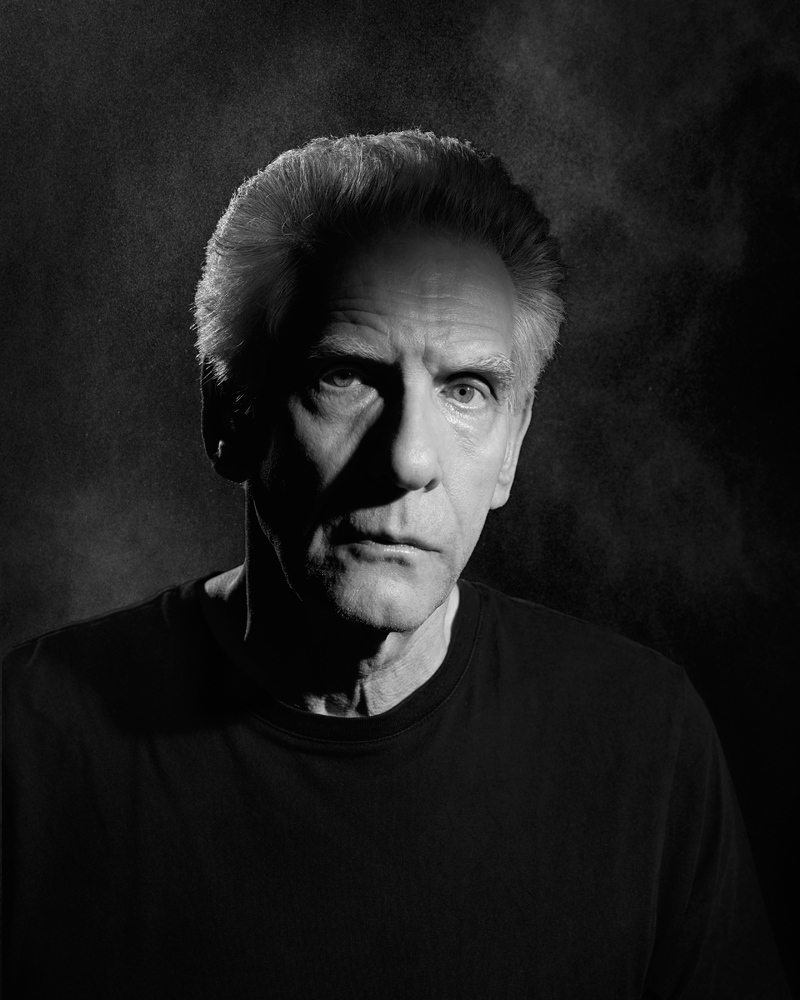

David Cronenberg

The techno-enabler for sex, for communication, for food, for everything, yes—I think it’s become necessary. David Cronenberg

David Cronenberg is an ideas man. His greatest movies—from the early body shockers of The Brood (1979) and Scanners (1981), to the psychosexual middle period of Videodrome (1983), Dead Ringers (1988), and Crash (1996), and up to the recent run that includes Spider (2002) and A History of Violence (2005)—are so tightly wound around the director’s ideas, and such elemental articulations of them, that their titles have become paradigms for the ideas they contain. Every movie about the Icarus-style perils of ambition to appear since, say, Jeff Goldblum invented teleportation and transformed himself into a hideous insect along the way in The Fly (1986) is in some small way in its shadow. Just as it would be unthinkable to make a movie about selfhood, narcissism, or identical twins without at least an acknowledgement of Dead Ringers, in which Jeremy Irons does a modern spin on the Castor and Pollux myth as a pair of obsessive gynecologists.

And even if he didn’t get to the ideas first (Kafka and Homer might have claims on the bug and the Gemini, respectively), Cronenberg has expressed his ideas so thoroughly it can seem to be something like prophecy. More than 30 years after the release of Videodrome, in which a television executive, played by James Woods, sort of merges with his TV VCR, to become a living, breathing broadcast of hideous acts of violence, we have YouTube to do the very same thing. The excessive and deranging gamification of our present lives, too, is not a far cry from that of eXistenZ (1999), in which gamers lose themselves in a virtual reality. And aside from, perhaps, the London gangster saga Eastern Promises (2007) and A Dangerous Method (2011), about the relationship between Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud, and Sabina Spielrein, Cronenberg’s movies don’t seem to exist in any real or realistic localities. Even his next feature, the gothic L.A. story Maps to the Stars, is, like all tales of Hollywood, a monster movie set in the metaphorical Tinseltown, rather than in the city as it really exists. The generics of their settings, though, give the films an archetypal, dreamlike reality, which lends them allegorical readings. So thin and garishly drawn is the Main Street America in A History of Violence, for example, not to mention the Rockwellian family who lives there, or the dead-eyed gangsters who come for them, that one cannot but hear in its continual celebration of the apple pie American Dream a metaphorical tremor of the historical violence upon which the country and its famous dream are built.

On the phone from his native Toronto, Cronenberg, 71, says that, in fact, reality—our perception and alteration of it—is the primary subject in an ongoing, scientific exploration that makes up the continuum of his work. The most recent installment of that work is a new novel, Consumed (out now from Scribner), which he’s been writing between movies for the last eight years. Opening with news of the murder and cannibalization of a renowned polyamorous intellectual in Paris and the disappearance of her famous philosopher husband, Consumed tracks a couple of pluckish, tech-obsessed journalists down some dark and twisting roads in their search for a scoop. At times as gory, ironic, and silly-fun as his films, Cronenberg’s novel shows him to be intensely interested in the workings of the modern world and still as fascinated as ever in the big ideas, and in technology as a conduit for human interaction.

CHRIS WALLACE: Is this the first novel you’ve written?

DAVID CRONENBERG: It is, actually. As a kid, I wrote some short stories that almost got published in Fantasy & Science Fiction magazine, which was a magazine I read. But I never did end up writing a novel. My writing has been screenplays, not prose, so I really didn’t know what to expect when I started to write it. Would I have a voice?

WALLACE: Did you enjoy the control of the medium, creating the scenery on the page?

CRONENBERG: Oh yeah. Screenwriting is a really strange hybrid beast, and a lot of very famous screenwriters are barely literate—if you can write dialogue and do some narrative structure, you can be a good screenwriter, even if your prose sucks. So I found novel-writing to be more like directing than screenwriting. In a screenplay, you write, “35 and handsome.” But when you’re writing that novel, you’re actually creating that living, breathing actor yourself. You’re doing the costumes, the lighting. That was kind of a revelation. It gave me some courage to continue. But the prose is prose, and there’s no equivalent in film.

WALLACE: The novel’s voice is very much you, as I know you from your films. But it is certainly different—fuller, maybe. More intimate? Are you a natural storyteller, the raconteur around the dinner table?

CRONENBERG: I wouldn’t say that I’m a renowned raconteur, but I can tell a story. And yet, it’s not only the story that I’m interested in. I’m interested in character and concept and philosophy and those things intertwine. It pleases me to hear you say that it sounds like a voice that you know, but wouldn’t necessarily find in my movies. I’m seeing a few reviews that say, “It’s basically Cronenberg revisiting his early movies,” and I don’t feel that can possibly be true.

WALLACE: You seem to feel freer to be more discursive within the form. There is even a sort of Paul Auster-y digression in the center of this book that feels of a different, postmodern narrative style than what your movies deal in. But the media have always had an intolerance for an artist who’s accomplished in one field entering into another. I call it the Ethan Hawke conundrum. When Ethan Hawke writes a novel, or even directs a film, you can feel this almost vitriolic response: “Just be an actor, we don’t want to read your novels.” I think that’s lessening now, as media begin to smear together …

CRONENBERG: I think there’s some of that. Listen, even doing a movie that doesn’t fit the mold that has been built for you annoys people. They’ve had you pegged as one thing and knew what to say and think about what you do. But with something that’s not the same, how do they deal with that? There seems to be some pathology attached to it. I don’t know what it is. But the freedom you’re talking about is real. I was reading a piece that Rick Moody wrote about the making of The Ice Storm [1997] from his novel, and he said that a novel could be first person, but that almost all cinema was third person. That really struck a nerve. I found that working in the novel form was much more personal—not in terms of personal details of your life—but more intimate. And, yes, you have much more freedom of form than you do in a commercial movie. It’s certainly not less demanding, but it’s weirdly less formal.

WALLACE: And it doesn’t require hundreds of people and millions of dollars to make.

CRONENBERG: It doesn’t, no. But the origin of the novel was this: Nicole Winstanley, who is now president and publisher of Penguin Canada, got in touch with me and said, “I’ve seen all your movies, and I really think that your sensibilities would work well in a novel. Have you ever thought about writing a novel?” And I said, “Well, only for about 50 years,” because I always thought I would be a novelist. My father was a writer—not a novelist, but a journalist. I used to fall asleep to the sound of his typewriter, from the Underwood mechanical to an IBM Selectric. I always aspired to be an obscure novelist, because I really liked discovering novelists who were basically unknown to the general public. Like, suddenly you find Djuna Barnes and her book Nightwood, for example. I thought it would be great if I were one of those whose work you stumbled across. And when I got kind of derailed into filmmaking, which I never thought I even had access to, I thought I’d like to be an obscure filmmaker. Unfortunately, if you’re obscure, you can’t get financed, so that was a problem. [both laugh] So in a way, the novel is like coming back to an old, beautifully established, and not totally buried aspiration.

WALLACE: Well, now it makes sense that you have this wonderful couple of radical lefty philosophers at the enter of the book. And like a lot of your works, which have a big idea at the center of them, the novel is very localized around a core concept. Or is it? Is Consumed—which seems to run on a spectrum from consumer culture to the consumption of one another—uniting these things in a commentary on desire and fulfillment? Or is it a very clever pun?

CRONENBERG: It’s not exactly a pun, no. It’s what [the philosopher character] Célestine said, that desire for anything is life. Desire drives life forward, is a continuation of life. It can be the desire for something really superficial or trivial, but at least it’s desire. It’s when there’s a lack of desire, then life ends.

WALLACE: And that the body is a commodity, which is the core of the couple’s politics.

CRONENBERG: That it can be, and perhaps it’s inevitable that it shall be. Their twist on everything is that the things that would normally be considered evil and bad and corrupt for them can be seen as life-enhancing and enabling—consumerism as a positive way of living life.

WALLACE: You can go a long way in describing a character these days by just listing their brand affiliations: they’re a Mac person, a Levi’s guy, Nike, Gmail, Ketel One, Horizon Organic, etcetera.

CRONENBERG: Absolutely. And, in fact, you can tell by the forums how existentially fraught it all is. Someone who’s a Nikon person attacking a Canon person is like what they say about schizophrenics. For somebody else, it’s just an argument: you lose it, you win it, no big deal. For the schizophrenic, it’s a question of existential dread to lose, like losing your self. Your very being is gone, evaporated. And that’s what you get on the forums about the most ridiculous aspects of a particular brand and item that they’re defending, the troll society. The Canonites trolling the Nikonites. [both laugh] It’s pretty disturbing, really.

WALLACE: I get that there’s always been this exteriorization of self going on there, like some tribal semaphore—”Hey, you of like mind and like brand affiliations, we can be cool.”

CRONENBERG: Well, it is tribal, though. It does have the passion and the exclusiveness of tribalism. The internet has made that possible in a way that couldn’t have existed before.

WALLACE: At one point in the novel, Célestine’s husband Aristide says that popular imagination is becoming the only imagination that exists: the media imagination, the jokes on the internet, the meme culture, which, in a way, you prophesied in Videodrome: Beheadings are broadcast worldwide, instantly; the exhibitionism of Instagram …

CRONENBERG: And the irony is that I never thought that my job as an artist was to be a prophet—unlike some well-known sci-fi writers, like Arthur C. Clarke, for whom it was a coup to predict satellite communications. I wasn’t interested in that aspect of it. However, I did have my antennae finely attuned to what was going on at that moment. And, without knowing it, I could sense some things. If you’d asked me, I wouldn’t have said, “This is the way that the world is going.” But in retrospect, it’s pretty obvious.

WALLACE: Fellini, in an interview for this magazine many years ago, said, “Any work, be it a book, a picture, music, or a film can be considered a means to free oneself from an obsession.” When you’ve completed a film, or, in this case, a book, do you feel cleansed of the obsession that inspired it?

CRONENBERG: It is more a passionate interest, curiosity. I certainly don’t think of them as obsessions. And because the work is kind of a continuum, I don’t feel that specific catharsis of finishing a particular work. It’s all a philosophical investigation. It’s a discussion with yourself about what it’s like to be a human being at the moment that you’re having that discussion. That’s ongoing and can segue from movie to movie, or form to form. Though I love Fellini completely, and it’s unbelievable to me that people don’t think about him anymore.

WALLACE: One of the currents in your particular continuum is this consideration of suicide—self-sacrifice of the hero, whether for the greater good [in The Dead Zone (1983), Scanners] or in compassionate removal [Dead Ringers]. It’s there in Consumed, too. Years ago you said that suicide is a fantastic exit—though you may have been speaking as a dramatist there—and, at another time, you said that, in making people die onscreen, you’re rehearsing your own death.

CRONENBERG: Yes, that was ultra dramatic and said long ago. [laughs] But there’s absolutely some truth in it. Ending your life is an extraordinary concept. You can understand why various religions totally condemn it—not all of them; some do quite the opposite, as we see every day. But when people do it, it emphasizes that it is available to anyone at anytime. And, so much of life is self-preservation—not just human life, but animal life—the absolute opposite of suicide. You might say that it’s only truly available to human beings because you have to have the self-consciousness that only humans have before suicide could even be considered. In recent years it has become very politicized, of course, because people are living longer and therefore suffering more, from stranger, obscure diseases—often very painful, exotically painful, to the point where no drugs can help. I’m 71, so I’m probably past a particular kind of suicide—the died-way-too-soon kind of suicide. But it’s a sort of strange, hidden source of power that everybody has.

WALLACE: There is an idea—given voice in Crash, A Dangerous Method, and others—that the death wish, the self-destructive urge, is really a creative urge, a pining for transcendence, liberation, even. Is that a sort of personal manifesto?

CRONENBERG: It’s probably a lot less dramatic for me, personally. I think I’m much more middle-class normal than you might think. [laughs] But I’ve noted the potential of it, yeah, and therefore it’s interesting for me to inflict that on my characters, or, rather, imbue my characters with it. Ballard plays with it a lot, and to some extent, Burroughs. I always say that you are a scientist when you’re an artist. You are experimenting with your characters, experimenting with modalities of living that are different than the one that you are actually living yourself. You are transcending your own life.

WALLACE: A lot of the human interaction in your films and in the book happens indirectly—through technology or, in the case of eXistenZ, on a whole other plane. People have straightforward sex, occasionally, but almost in a provisional way. Do we need a facilitator to really connect with one another?

When things go wrong is when things become illuminating. David Cronenberg

CRONENBERG: The techno-enabler for sex, for communication, for food, for everything, yes—I think it’s become necessary. I’ve always seen technology as an extension of us. So it makes sense that technology becomes part of us, it returns to us. In the ’50s, a lot of sci-fi was presenting technology as dehumanizing, but really, it’s nothing but human, all the best and worst parts of ourselves. Think of the war machinery we’re seeing every day—it’s how our fantasies of power become metalized, but it’s still us. So, that technology should infuse our lives, that it should intertwine with our lives, right into our bodies, is inevitable. As far back as we can see, civilization has been that way. But because it’s become more sophisticated and more ubiquitous, it’s become a facilitator of every aspect of our lives, including sex. And that’s fascinating to me, always has been.

WALLACE: Your movies seem very interested in the way the brain works: from the possessive force of fear and paranoia [The Brood, Scanners] to disorders of function and identity [Spider, Dead Ringers] to the theorizing of Jung and Freud [A Dangerous Method]. Do you spend as much time considering the way you work as you do the way the world is working? Is your antennae turned inward, in other words?

CRONENBERG: I do it by turning them outwards, really. And then it reflects back. I’m not the kind of person that is constantly mulling over his own reaction to things and second-guessing himself, worrying. I am fascinated with what reality is, because it became obvious to me very early on that reality is neurology. It only takes one LSD trip—which is the only LSD trip I took [laughs]—to make very clear that reality is a question of how your nervous system and your sensory organs work. Reality for that dog sitting at your feet is a totally different thing from your reality, and if you could modify your senses, you could move yourself into the dog’s reality. It’s hard to accept, because the world feels so solid and real, and the colors seem so definite and absolute, but it doesn’t take much to realize that that’s not the case. Philosophers like Kant and Plato have driven themselves crazy trying to figure out the reality behind the reality. So that meditation on the brain and nervous system—what happens if you change it, how we do change it, even by drinking alcohol—becomes a meditation on reality. How do we perceive it? How do we live in it? So, once again, it’s not just a question of people being destructive, it’s a question of people trying to transcend their own reality.

WALLACE: Is that where your early fascination with horror or shock or gore came from?

CRONENBERG: Yeah. You know, they talk about me as the inventor of body horror. But I’ve never thought of it as being horrific. Of course, you’re being a showman, and if you’re making a low-budget horror film—there were a lot of those around at the time—how do you get yourself noticed? Certainly I was in the world, and not an abstractionist. I was trying to make movies and continue to make movies. But there’s the philosophical underpinning for all of it. If neurology is reality, that’s an incredible theme—how to structure a narrative that will discuss that? Immediately you’re into changing the body to change the reality, and that’s what led me to all of those things like Videodrome.

WALLACE: Your characters’ work is often their religion. And there is that great scene in Dead Ringers where they’re putting on the robes and it’s almost like they’re these popes—

CRONENBERG: Cardinals.

WALLACE: Exactly. And, in every case, the work corrupts their life, or vice versa. Is that purely a narrative device, or do you feel like you live your work and your work lives you?

CRONENBERG: Dead Ringers would be my meditation on a work-life balance, you think? [both laugh] No, I’ve never quite thought of it that way. I never really felt like I had a job. As someone who is very antireligious, I wasn’t particularly interested in giving my characters religious belief. I didn’t want to encourage that, actually. [laughs] In fact, all my agents have known never to send me a project with the devil, apocalypse, even ghosts, because I’m just fairly anti-religious, without getting militant about it. I’m aware, of course, that people, including myself, need structure, need a system of activity that has rules and strictures, so it’s natural for me to find it in scientists, in artists, in sort of subterranean cultures, little cults. I’m very interested in the creation of reality that a group of people will do together. But there are so many ways that one can do that. Religion is only one of them. So I choose to go with things that often end up being some kind of work, or, as is the case of Crash, a kind of subterranean cult.

WALLACE: They’re enthusiasts. And I swear that there’s probably a group of car-crash fetishists in Brooklyn re-creating famous accidents like Elias Koteas’s crew in Crash.

CRONENBERG: I have no doubt it’s true. [laughs]

WALLACE: But, to quote Fassbender as Jung in your movie, “There must be more than one hinge into the universe.” Even on a secular level, you are often considering things like determinism versus free will and making these concise, modern myths about modes of behavior gone too far. Do you think of them as commentary?

CRONENBERG: Going too far is something that everybody is constantly worried about, on every level—whether they’re worried about terrorism or the revolt of their own body through cancer. For everything that can work on one level, there’s the point beyond which it’s too much. For a dramatist, that’s what you’re looking for. When things go wrong is when things become illuminating. So much of our understanding of the human body comes from the need to deal with disease, things that we would never have thought to consider.

WALLACE: Were there breakthrough moments for you when you felt like, “Oh my God, I made it!” or, “I’ve stepped up to a new level”?

CRONENBERG: It’s not just me, it’s my crew, who I’ve worked with for many years. I’ve worked with my cameraman Peter Suschitzky since 1988 with Dead Ringers, for example. And there were many moments where it felt like we were working at the top of our game: Dead Ringers, certainly, because it was so technologically difficult. We had to invent some technology on a very low budget to make that movie happen, and it was so dark and complex emotionally that you have to think it’s a high spot. It’s very satisfying.

WALLACE: We hear a lot these days about great filmmakers—Soderbergh, for example—growing so frustrated with the industry that they’re going into other media.

CRONENBERG: It is increasingly difficult to make an interesting movie, period—let alone get it distributed. In fact, there’s been some talk about Maps to the Stars being video on demand only in the U.S., and not actually having a theatrical release. I don’t think that will happen, but contractually it could. And the feeling is that’s where you would make your money.

WALLACE: Well, to be honest, that’s where I watch all my movies now.

CRONENBERG: Sure. See, to me, that’s no terrible loss. I don’t go to the cinema myself. There is a huge paradigm shift, but it’s not all bad. People watch movies in a different way now. But that wasn’t the reason I wrote a novel. It’s true that Jean Renoir and other well-known directors wrote novels after the point where they couldn’t get movies made, but that hasn’t been the case for me. In fact, I have five producers who want to make a movie out of my novel. But that’s not something I want to do, actually. I’ve done it already. The novel actually exists. It’s complete in itself. And then I thought, “Sell it to some other director—let him direct it.” I’d be interested to see what somebody else would do with it. I don’t need to make another movie. The next thing I really want to do is write another novel.

CHRIS WALLACE IS INTERVIEW’S SENIOR EDITOR.