Daniel Craig

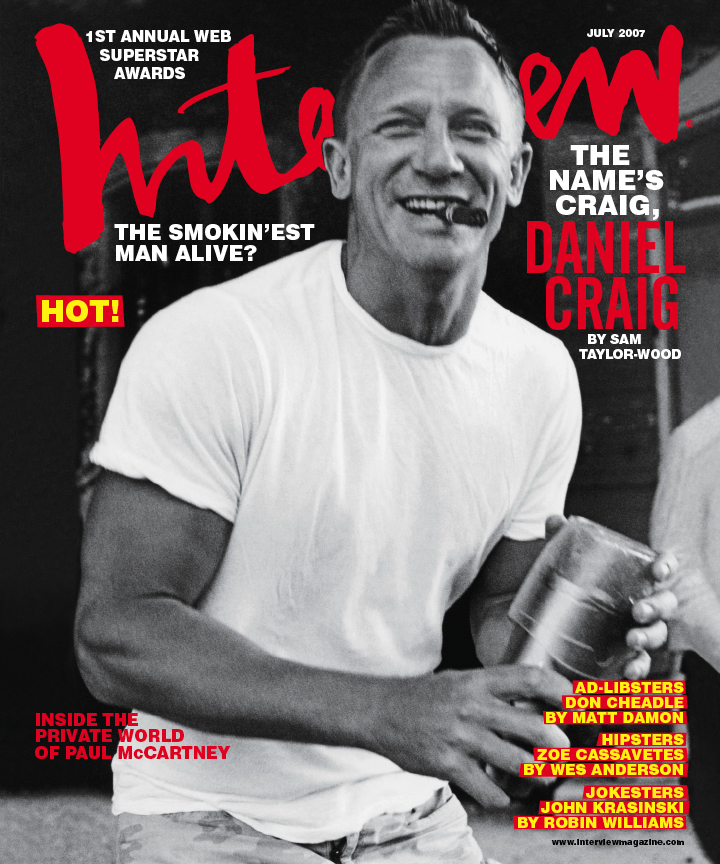

While the 007 traditionalists were obsessing over the color of his locks, Daniel Craig set about imbuing the Bond franchise with new life—in the process fashioning the most rascally delicious version of the character yet, and earning himself unequivocal heartthrob status. Still, don’t expect a career dominated by car chases and cat-and-mouse games. As the actor reveals here in this candid conversation and these intimate photographs by artist Sam Taylor-Wood, he’s got something much bolder up his sleeve.

After a long day of relentlessly photographing her subject and longtime friend, Sam Taylor-Wood sits down at a local Italian restaurant, London’s Locanda Locatelli, to begin the interview portion of her Daniel Craig story—two hours of intense conversation that included a small portion that went unrecorded (and is therefore not presented here) when she forgot to flip the tape.

SAM TAYLOR-WOOD: My first question was going to be: Do you like clowns?

DANIEL CRAIG: Is that from Angelica [Taylor-Wood’s daughter]?

TAYLOR-WOOD: No. It’s something I find divides people.

CRAIG: Oh. Does Angelica like clowns?

TAYLOR-WOOD: No. I took her to the circus in Basel [Switzerland], and two clowns set each other’s bums on fire. She was 3, and the whole time she just kept saying, “Clowns, smoke, fire, bottoms.”

CRAIG: Sounds like a night out! But no, I don’t like clowns. And then there’s all that bollocks about clowns being wise. Shall I talk about bollocks?

TAYLOR-WOOD: Yeah, for as long as you like.

CRAIG: You know I can! I was on these press junkets for Casino Royale, and I’d get asked the same questions…. What are you doing?

TAYLOR-WOOD: Sorry, I may have to undo my trousers—they’re too tight… Carry on!

CRAIG: So I was on these press junkets, and you have to reinvent everything you’ve already said. Wind an actor up and set them off, and all they want to do is talk about themselves—you have to be a little self-obsessed to be in the business. It’s the worst and very best thing about any art form.

TAYLOR-WOOD: I think that to be an artist you have to have a big enough ego to believe that people out in the world want to see what you think is a good idea. And if you don’t have that sense of ego, then the minute that idea goes into the world, self-doubt kicks in.

CRAIG: You’re also opening yourself up and saying, “I’m going to allow people to judge what I do.” That’s a big step. The most important thing to remember is that once you’ve done it, there’s no going back. And whether you make it or not, whether you make money or not, it’s a career. And actually, there’s nothing like it. Because once you’ve gotten some real fulfillment from something, once you can say, “I’ve moved someone; I’ve made someone think differently,” it becomes like a drug, and you want to keep doing it. It’s the whole bollocks that comes along with it that I’m not sure about—you are judged, and the way people perceive you suddenly becomes an issue.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Well, I fucked up early on because I’m so open. If someone looks genuinely interested and asks me a deeply personal question, I’ll give the answer. I’m too open.

CRAIG: I do admire people who can control the way things like that happen. I can’t be like that. I don’t think many people can.

TAYLOR-WOOD: I wish I could be like that.

CRAIG: If they’re successful. People who are like that but who are not successful are not so interesting. But someone who has talent has to be precocious. When you see that they can back it up, you go, “this is serious talent.” Then you get into Muhammad Ali territory.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Yeah, they’re allowed anything.

CRAIG: So when you say, “Someone asked me a question, and I spilled my guts,” that’s the beginning of something… [waiter arrives at the table with menus]

TAYLOR-WOOD: Wow, food.

CRAIG: Should we order some wine?

TAYLOR-WOOD: Oh, yeah. White wine, if that’s all right. By the way, tell me if you think these are really crap questions.

CRAIG: Oh, I will. That’s something to completely relax about. [both laugh]

TAYLOR-WOOD: Anyway, I was wondering, what was the first moment when you felt like you were on your way? And beyond that, what did you yearn for when you’d gone past that point? Was it working with an amazing director, or working with an amazing actor?

CRAIG: Well, competition is so important, even when you’re an artist. And if you deny that there’s competition, then you’re a liar. That’s what gives you ambition.

TAYLOR-WOOD: What spurs me on is bad reviews.

CRAIG: Sure. When I did Love Is the Devil [1998], John Maybury [the film’s director] and I sat down and looked at our reviews. . We had one in the Guardian—they just loved the movie—and another in the Evening Standard where it was rubbished, and we both went, “That’s success.” It’s horrible getting bad reviews, but there is a certain amount of truth in every one of them.

TAYLOR-WOOD: The horrible thing is that I think more about the bad ones than they deserve. It can knock you down so hard.

CRAIG: Because to completely become an artist is to expose yourself. You can’t say, “Don’t look at me; I’m exposing myself.” If you’re going to do it, you have to do it all the way. Nobody’s going to take notice unless you step out of your own way and go, “Look at me!” It’s kind of a horrible trait, but we can trace it back to childhood, when the child who is the most noticeable gets the most attention. Do you think people are born artists?

TAYLOR-WOOD: Yeah. I went out of my way to try not to be an artist, because I thought I would end up leading a miserable, obscure life. I tried to escape it for as long as I could, until I had to admit at 25 that that was my path. Now, Love Is the Devil wasn’t your first film, but it was the first film that really pushed you out into the world, right?

CRAIG: It was the first film that I did that “made me.” I always wanted to make movies. When I met John Maybury, I knew he was the sort of person I wanted to be involved with because he was genuinely crazy and wonderful.

TAYLOR-WOOD: The obvious question is, will you want to continue working with people like that now that you’ve done Bond? Because I remember one drunken evening, when you were thinking about doing it, I asked you, “Will you still be able to do those movies, and will you still want to?”

CRAIG: You were just trying to wind me up.

TAYLOR-WOOD: And I was trying to talk you out of Bond—how wrong was I?

CRAIG: Well, I was in that situation, and I was asking all my friends what they though. I had my friend Baillie [Walsh, the writer and director] in my ear going, “You’ve go to do it,” though even he said that maybe it was not a good idea. At the end of the day, I realized it was my choice and no one else’s.

TAYLOR-WOOD: That’s it, and that your friends were just as confused as you were.

CRAIG: If I wanted to make spy movies for the rest of my life, that would be one thing, but I don’t want to just make spy movies. I also want to make movies that are difficult to make, like Baillie’s movie Flashbacks of a Fool [in which Craig is slated to star]. It’s the same deal.

TAYLOR-WOOD: It’s so fantastic—to be doing Bond films and The Golden Compass on the one hand, and then go off and do Baillie’s independent film.

CRAIG: Last night, just before I went to bed, the one thing I remember saying to myself is that we should talk about Baillie and you, and that I’m testing two friendships to the hilt—an Interview photoshoot with you and a film with my best friend; I could end up with no friends at the end of this.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Oh, don’t be stupid.

CRAIG: Yes, you say that. The thing is, we’re all in the same arena, and there’s a lot of crossover. And I’ve never had that blinkering vision about career. I’ve always gone, “I have to do this on my own because if I don’t, then how do I say, ‘This is mine?’ If I don’t, someone’s going to go, ‘I possess that.'” But actually nobody possesses what I’m doing. What I do is mine. When I see the way that the business works, it frightens me. Basically I’m forced to go talk to people about the business. And it’s a new lesson. But you know what? It’s a new place and a new stage in my life.

TAYLOR-WOOD: But it’s good that you learned it. I forcibly try to be naïve. But as we were saying earlier, we cross all boundaries as artists—film can go into art, art into film, actors into photography, and photography into whatever. If you are an artist you can extend your discipline to so many areas. So the fact that we’re doing this, and Baillie’s making his first film with you, is what it’s all about.

CRAIG: And when it comes to, “Okay, I could start using this to make something happen for somebody else, or I could use t to make something happen for me,” the former is more rewarding. You get into a situation where you can say, “Hell, we can make this happen. I’ve always believed in your talent.” Whatever you do, though, it’s a selfish business. When I accepted the job to work on Bond, I genuinely did it to change my life. I knew that it would flip everything on its head. I can say, hand on heart, though, that I’ve never made movies for money—I’ve always made them because I’ve truly wanted to do them.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Which is why—looking at your extensive resume, as I did last night—all your decisions and choices have been really food ones, because they weren’t about making money. And then you just go and do one when-bam-fucking-great-big-thank-you-ma’am of a movie, which is fantastic. I’m not denouncing it as anything but brilliant, because I think it was a terrific choice.

CRAIG: Deep down you are!

TAYLOR-WOOD: No. I’m not. I loved it.

CRAIG: Well, I hope you would tell me if you thought it was crap.

TAYLOR-WOOD: It’s funny because I can’t associate you with the big-movie-star image.

CRAIG: What, because it’s so far removed from me? [laughs] Like, “That tough guy up there, that can’t be you!”

TAYLOR-WOOD: That’s not Daniel! It just shocked me how good you are in such a special role!

CRAIG: Bond is supposedly the most-male moment, but to me he’s never been macho. That Bond is something that Sean Connery created in Dr. No [1962]. I don’t know Sean, but I wouldn’t want to meet him in a dark alley! He was a big, strong guy, and he has a big male presence about him. Everybody was in an uproar that he was going to be James Bond. He got shit because he was basically an Edinburgh bricklayer, and everyone who reads the books thought, How could he possibly do it? But he created a style that was unique and kind of sexy. There’s no point in trying to compete with every Bond that came before, though.

TAYLOR-WOOD: You managed to make it your own.

CRAIG: We will see.

TAYLOR-WOOD: You’ve already done it—we don’t have to see. And the only contentious issue when you were offered the part was the fact that you’re blond.

CRAIG: They just want more gags. The next one’s going to be a lot funnier.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Octopussy kind of gags?

CRAIG: Yeah. Octopussy. Pussy Galore. They’re all great names. But that’s the thing: all the Bond jokes have been flipped on their heads. They’ve all gone beyond… Should we order a bit more wine, so I can think straight? [food is delivered to the table]

TAYLOR-WOOD: Imagine being married to Giorgio the chef here! Can you cook?

CRAIG: Yes! But not like Giorgio. He’s an artist. My mother gave me a real kick toward cooking, which was that if I wanted to eat, I’d better know how to do it myself.

TAYLOR-WOOD: So what do you think of the new Marmite with Guinness?

CRAIG: It’s so—it just tastes like Marmite with Guinness.

TAYLOR-WOOD: No, it tastes like Guinness!

CRAIG: Okay—7:30 in the morning. I’m buttering my toast and then putting Marmite with Guinness on it. I can’t taste anything at that hour, but Marmite is so great it’s like [makes screaming sound], it wakes you up! [laughs] Like, “Welcome to the day!” I’ve just put axle grease in my mouth…You know, I was Mr. Marmite—that’s how I got my equity card.

TAYLOR-WOOD: [laughs] No, it’s not true!

CRAIG: It is! At the Reading Save-a-Center. I was Mr. Marmite. I wore a Marmite Jumper.

[break in recording due to Taylor-Wood’s having forgotten to flip the tape]

CRAIG: This is like some sort of drunken conversation. I can’t remember what I just said!

TAYLOR-WOOD: It’s fine.

CRAIG: No, it’s not. It’s terrible!

TAYLOR-WOOD: No, it’s totally fine.

CRAIG: Are you going to yoga tomorrow morning with Satsuki [Craig’s girlfriend]?

TAYLOR-WOOD: I said I would, but now I think I’m filming a dead swan.

CRAIG: [both laugh] I love that my friends are all freaks. And now I’m getting interviewed by one!

TAYLOR-WOOD: Tell me about going to the Oscars.

CRAIG: I found that all people want to do after the Oscars is just go somewhere and relax. They want to go take their wigs off. I kept saying this to people there, giving them this information when I was pissed [drunk]. And then I’d look up and think to myself, Oh, my God, you’re wearing one! [Taylor-Wood laughs] So I went, “That’ll be me in a couple of y ears.”

TAYLOR-WOOD: You can’t ever wear a wig, though.

CRAIG: Oh, but I can! [laughs]

TAYLOR-WOOD: But then you can’t ever take it off!

CRAIG: The whole thing about the Oscars used to be that it was this “in” thing, because the industry was so protective. You felt really safe, like you could get drunk and fall over and no one would write about it. I never went to the Oscars then, obviously, but I’ve heard stories. Apparently people sat at tables and drank vodka martinis, and then somebody went, “And the winner is…”

TAYLOR-WOOD: When I went to Los Angeles to photograph young, up-and-coming American actors—

CRAIG: How young were they?

TAYLOR-WOOD: Younger than you! [both laugh]

CRAIG: [speaking into the tape recorder] I’m stabbing her now!

TAYLOR-WOOD: [laughs] But anyway, if it was 15 people, 13 of them turned up with hair, makeup, PR, agents—everything is so controlled that when you do get to the post-Oscars party, you just want to go crazy and have a fantastic time and be relaxed.

CRAIG: But this is the danger of doing this interview. You and I looked up old interviews and photographs from Interview together, and we went, “Wouldn’t it be great if that could be the way it is now?” But today we have to worry that something we say will be repeated around the world, ad infinitum—”James Bond said this,” or “He doesn’t like that.” I’m now in that place where I either just go, “Fuck it. I’m having a conversation with you as my friend, and this is one of the reasons I’m doing this interview,” or I carefully consider every word I’m saying.

TAYLOR-WOOD: The great thing about Interview, though, is that when you read the old issues it’s gossip, it’s art, it’s movies, it’s what it should be! Two relaxed people exchanging ideas.

CRAIG: Unfortunately, most people in the arts now want to be political. I don’t have a problem with anybody using their weight or their artistic clout to make a difference politically. I mean, if you have any clout and you can do some good, go for it. The problem is that artists with political voices make me nervous—artists by their very nature are political, but they’re political in spite of themselves. Or should be political in spite of themselves. And as soon as you start trying to cross the boundary, you have to make a decision—you’re either one or the other. That’s why The Lives of Others is such a wonderful and beautiful film—it shows that there’s a lot of negativity toward being an artist or a person who creats. I do it all the time myself, saying, “Eh, acting, what is it? It’s just a job it’s about dressing up and showing off.” And it is, basically, but I’ve been trying to do both as much as I can for as long asi can remember, because it’s found me attention—

TAYLOR-WOOD: Ladies’ dresses?

CRAIG: Anything I can get my hands on! [both laugh] But seriously, without that desires to show off, we don’t exist.

TAYLOR-WOOD: The great thing is that because of Bond you will do movies like The Lives of Others. I don’t want to do the I-remember-when-I-first-met-you thing, but I remember that first play I saw you in—the one by Caryl Churchill.

CRAIG: A Number.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Yes. It was quite a difficult play for you to have done, playing three different sons, two of whom are clones. That was such a brilliant thing to be in!

CRAIG: I’m the foot, though. Stephen Daldry offered me a new Caryl Churchill play at the Royal Court Theatre, and I didn’t even read it. I should have read it because when I did—after I’d said yes—I went, “Fucking hell! How am I going to do this?”

TAYLOR-WOOD: Yeah, but it was brilliant. It was the moment when I became interested in you. Do you have plans to do more theater?

CRAIG: I don’t.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Is it difficult to take the time now that you’re doing so much film?

CRAIG: I guess, but you can do short runs. I’ve been offered a couple very recently, but they’re sort of old plays—lovely old plays, but I suppose if I’m going to do something in the theater, then I want to do it with a new writer.

TAYLOR-WOOD: It’s nice to premiere something.

CRAIG: It is, even if in theory the risk is greater. You just hope that an audience comes and looks with fresh eyes. I’ve never really had a desire to do Shakespeare, although I totally understand the reason for doing it, and the incredible muscular exercise of it. For me, it’s just too many lines. [laughs] Though it’s fantastic when it’s done well.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Seeing a new play in a first-time production is so exciting—when it’s good you want to shout from the rooftops. It must be amazing to feel like you’re part of something first. I don’t know whether you’re aware of that at the time, though.

CRAIG: I don’t think you should be—that’s other people’s jobs. When you’re doing it, you should just be focused on making it as good as you can. [speaking into the tape recorder] Sam Taylor-Wood leaves the table… She said she needed to pee… but I’m not sure.

A few days later Craig and Taylor-Wood meet in Sicily, where they resume their conversation.

SAM TAYLOR-WOOD: What are your next film projects?

DANIEL CRAIG: I’ve got this Baillie Walsh film that I mentioned the other day—he wrote the script five or six years ago for me, and we’ve been planning to make it for a long time. Now it looks like it’s set for this summer, but, of course, these things don’t always happen.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Tell me about your character.

CRAIG: He’s a washed-up movie star. It’s about going home and how some people run away from home not just because they’re unhappy, but because that’s hwat they’re genetically predisposed to do.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Is it redemptive?

CRAIG: Yeah, but it’s not forgiving. Once you break those ties, they’re gone. If you try to artificially reconnect them after 25 or however many years, it doesn’t work, because friendships need constant work.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Is it a small, independent film?

CRAIG: Yeah, you could say that, but with a big budget. What’s really wonderful and great and awful about the film industry is that you can make movies like this, but you might not be able to get proper distribution, so a lot of people might not see it. But the fact that I’ve done Bond might get 10 more people into the cinema that would not have gone to see it before.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Doing Bond has enabled you to do a lot more films. So what are your criteria for picking projects now?

CRAIG: The criterion is, is it interesting? You often do jobs in response to what you’ve just done. If I’ve just played a crazy loon in one movie, I don’t necessarily have the urge to go out and play another crazy loon for a while. I’m most likely not going to take any more spy roles in the foreseeable future. But then you never know—there might be something I can’t pass up.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Action heroes?

CRAIG: I don’t think I played Bond like an action hero. Do you?

TAYLOR-WOOD: No. You made him intelligent again. Am I right in assuming that this was the first time Bond was up for a BAFTA?

CRAIG: You assume correctly.

TAYLOR-WOOD: That’s something to be hugely proud of.

CRAIG: I am. What was great was the public voting to give Eva Green the Orange prize—the best newcomer award. Maybe we didn’t win the footrace as far as the BAFTAs were concerned, but winning the Orange prize was a real testament to the public view; they went to see it, they genuinely seemed to like it, and they voted for it, so all those things tied together made it a special experience.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Were you ever a boxer?

CRAIG: No! Why do you ask? Because I’m bullheaded and have a broken nose? Actually, I never broke it, but I kind of smashed it doing something—something that was actually quite dull.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Is The Golden Compass your next big film?

CRAIG: The next big film is The Invasion, which is coming out in the summer—it’s going to be an interesting movie.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Didn’t they switch directors or something on that?

CRAIG: Thank you for asking that leading question. Actually, they didn’t switch directors, but they did make me do some reshoots—there’s no use in trying to hide it. It’s quite weird, but sometimes it happens; someone will come out and ask various questions about the film, and all of a sudden you’re told, “You have to go back and do lots of reshoots.”

TAYLOR-WOOD: Is that because the minute you get somebody else on set it changes the tone?

CRAIG: More because the film went in one direction, and once it was done certain people discovered it wasn’t the direction they wanted it to go in. [Craig’s girlfriend, Satsuki Mitchell, enters the room with a friend]

TAYLOR-WOOD: That is such a gorgeous dress!

SATSUKI MITCHELL: It’s good, isn’t it? It just needs pockets.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Have a chocolate biscuit!

CRAIG: Um, guys…

TAYLOR-WOOD: Yeah, go on—we’re working here!

SM: [laughs] Then don’t’ ask us out here for coffee and biscuits!

TAYLOR-WOOD: Now, both of your upcoming projects—The Invasion and The Golden Compass—co-star Nicole Kidman. Is that because you work so well together?

CRAIG: I do like her. She’s great.

TAYLOR-WOOD: She’s gorgeous.

CRAIG: Yeah. And she’s become a perfect friend, which is very nice. You don’t make friends that often on the set.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Why is that?

CRAIG: When you first walk onto a film set, it’s the most wonderful thing, like running away to the circus. You feel like you’ve gone to a special place, because everybody works very intensely and parties very hard and gets on with each other because they have to. On the whole, people are genuinely nice, and you end up with a million phone numbers—a million phone numbers that you don’t call. It’s kind of sad, but when I arrived on the set for the Bond movie, I knew at least 80 percent of the crew—I had worked with them before on other jobs over the years. So in a weird way, despite the fact that it was sort of a strange place to be, it was kind of reassuring that I knew all these people. But when you finish a job, you say goodbye to each other, and you give each other a big huge, and you go, “I’ll see you on the next one.” Because everybody’s got a life, and you realize you’ve got to go back to that life.

TAYLOR-WOOD: I remember reading an interview with Malcolm McDowell where he said that [Stanley] Kubrick and he were as close as an actor and a director could be through shooting A Clockwork Orange [1971], but that the minute it wrapped, Kubrick never spoke to him again and refused to take his calls. That’s quite hard.

CRAIG: It is, but it makes sense. When you accept a job, you give yourself over to the director, whether they’re passive-aggressive or manipulative or whatever. If you choose to go down that path because they’re good at what they do, that’s our choice, but you should never expect to be friendly at the end of a movie.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Does the choice of director influence the films you decide to do?

CRAIG: Completely.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Even if the script is merely okay?

CRAIG: Yeah. You kind of sell yourself over to it—you have to.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Because you’re walking hand in hand with someone you trust completely?

CRAIG: Well, maybe you don’t trust them completely. But what you’re saying is, “For this moment in my life, I’m going to give myself over to this, no matter what happens.”

TAYLOR-WOOD: It must be weird and difficult when you get someone who’s completely crazy or—

CRAIG: Or useless. That happens. But as long as the work’s getting done, then it doesn’t matter how crazy people are. If someone’s good at their job, then there’s room for craziness, and it can even be helpful.

TAYLOR-WOOD: I imagine it’s nice, though, in the sense that every time you make a film it’s a completely new experience, not just because of the character but because of the director.

CRAIG: But you have to make that happen. I’ve done movies back to back, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re going from a slapstick comedy into some deep tragedy; if you’ve done too much of it within one year, it’s just a movie set. Ultimately the mechanics are exactly the same, regardless of what the acting’s about. You can really drain yourself of anything even slightly productive. But you’ve got to be careful about that.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Is working with a good director like when you go to a party and somebody walks into the room with that incredible energy that turns everything around?

CRAIG: If that happens, I try to leave as quickly as possible! [both laugh] Like, “oh, fuck, here comes trouble!” But with a director, I don’t think it’s something that happens on the first day. I mean, some actors do it, some directors do it, and some members of the crew do it: They come on shouting because they want to be known as the person that you can’t fuck with. And if someone comes with that, that’s all well and good, but you cannot sustain it for four months or however long the shoot is. Actually, some people can, and it’s quite incredible to watch. I tend to be more like, “Tomorrow is another day,” and I’ll get you back. People fuck with each other on film sets, but I like that as long as it’s not destructive. Apparently Robert Altman was like that, but in the loveliest way. He enjoyed playing people off each other or just brilliantly winding them up—which didn’t mean he didn’t like you. Because everybody trusted him, they were happy to have that done to them. That is a great place to be.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Those are the sorts of people you wish you could work with.

CRAIG: Robert Altman, definitely. I’m really sad he disappeared from this earth, because I just loved every film he ever made. Even his less successful ones have a tone that you feel emotional about. And John Huston would have been someone I’d have liked to have worked with.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Is it difficult to say living directors you’d want to work with?

CRAIG: All of them! [both laugh] Anybody out there who wants to give me a job, I’m very happy—they’re all wonderful, beautiful people!

TAYLOR-WOOD: So what have we covered? We’ve talked about upcoming films, theater—

CRAIG: Period dance?

TAYLOR-WOOD: Period dance! Daniel can dance to anything in any style. He’s been practicing in front of the mirror.

CRAIG: I have not! It’s an inner feeling. Dance comes from within. Ask Pina Bausch!

TAYLOR-WOOD: [laughs] Okay, tell me about growing up in Liverpool.

CRAIG: Very happy and very ordinary in may respects. I lived just outside Liverpool with my mother and my sisters. At the time, my life probably seemed quite extraordinary, but actually it was very ordinary. I went through school, failed my Eleven Plus Exams [an exam that was given to students in their last year of primary school], went to a secondary school with little money, but we had a good drama department.

TAYLOR-WOOD: Was that drama department what kick-started acting for you?

CRAIG: Not really—Mum took my sister and me to the theater all the time. I kind of fell in love with the idea of acting because she knew actors. I liked the idea of it—you know, shouting a lot and dressing up and all that. But I tend to keep genuine growing-up things as private as possible and don’t go into detail. It’s nobody else’s business. It’s all very well to get me to go and do a magazine piece and sound off and tell stories, but my memories are as selective as everybody else’s, and people recall things in different ways. I mean, I could say, “I grew up in this house, and the front door was red,” and someone could go, “No it wasn’t—it was blue!” But if you stick with feelings and emotions, you’re in safer territory. It’s kind of unfair to ask someone to do more than that.

TAYLOR-WOOD: It is. So is it true that you ran away to the circus at 11?

CRAIG: Yes! I was lion-taming by the age of 12.