DIRECTOR

Cord Jefferson and Ryan Coogler on Their Unlikely Climb to the Top

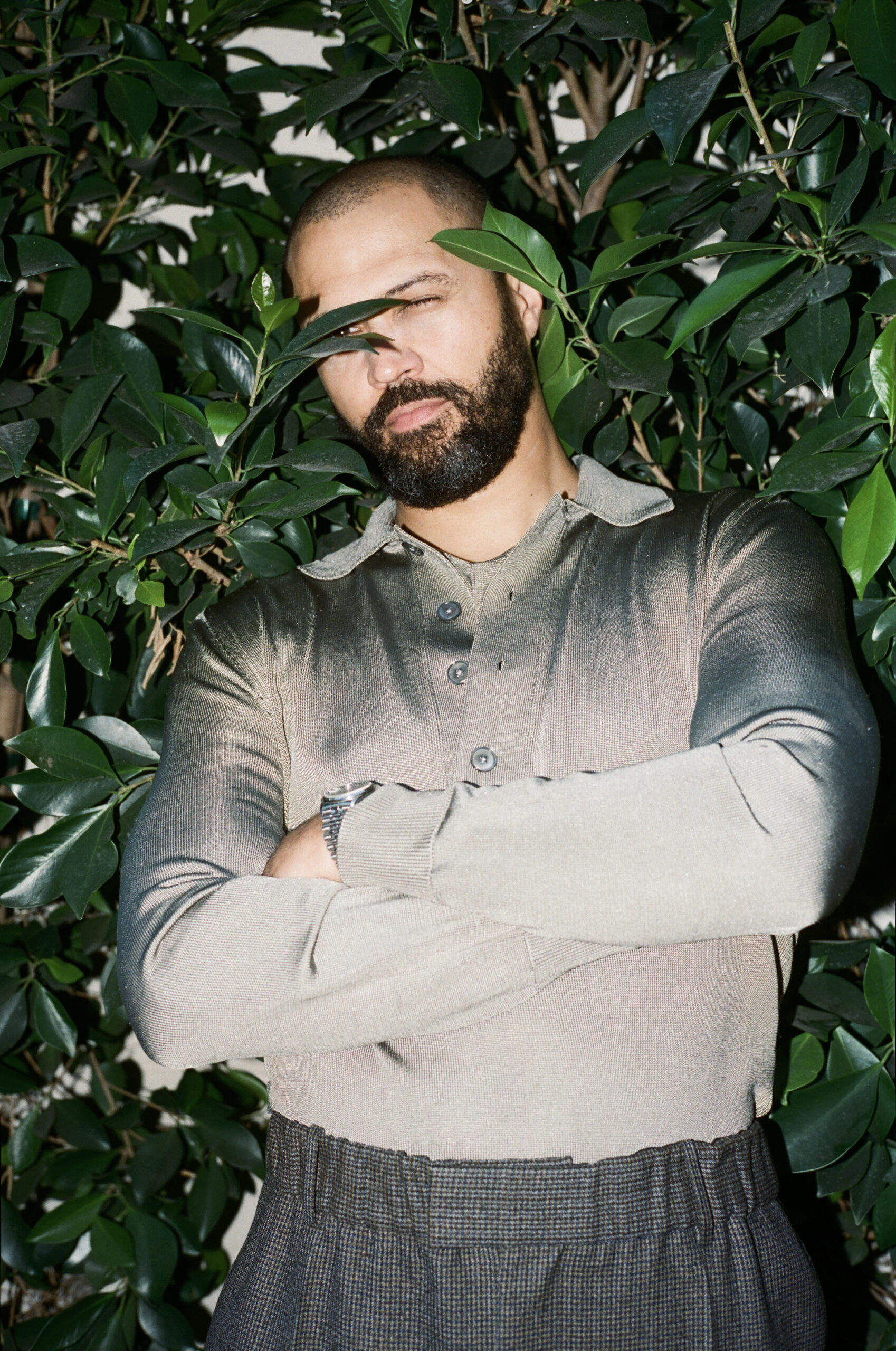

Cord Jefferson wears Jacket and Shirt Brunello Cucinelli. Pants Dior Men. Watch (worn throughout) Cord’s Own.

Cord Jefferson spent the early part of his career freelancing as a journalist and at one point editing for Gawker. So he has a hard time believing that today, he’s sitting in a production office on Melrose Avenue being interviewed by Ryan Coogler, the award-winning director of the Black Panther movies. But that’s reality when you successfully make the leap into Hollywood, first as a TV writer (Jefferson won an Emmy for his work on the HBO series Watchmen), and now as the writer and director of the best picture contender American Fiction, a searing satire about a disgruntled writer, played by Jeffrey Wright, who decides to do something about the publishing industry profiting off Black tropes. How exactly did he do it? Ryan Coogler finds out.

———

RYAN COOGLER: Good to see you, bro.

CORD JEFFERSON: You too, man. I don’t know if you know this, but I interviewed you—

COOGLER: What?

JEFFERSON: For Fruitvale Station [Coogler’s 2013 debut feature].

COOGLER: No.

JEFFERSON: Yeah, like six years ago when I was still doing journalism.

COOGLER: That’s crazy, dog.

JEFFERSON: Yeah. I wasn’t even working in TV yet.

COOGLER: Did you know you wanted to do this?

JEFFERSON: Yeah.

COOGLER: When did you know?

JEFFERSON: It took me a long time to be able to think of myself as an artist. Growing up, I didn’t know anybody who made art for their career. I knew people who played in bar bands on the weekends or were hobbyist painters, but I didn’t know anybody who was an artist. That felt like something that people in New York and L.A. did. I was a kid in Arizona. My parents didn’t have a bunch of money. It felt like something that was out of my reach. So I started out in journalism, I think, as a way to scratch that creative itch.

COOGLER: Right.

JEFFERSON: I was always interested in film and TV, but it felt like there were so many barriers to entry. I lived in L.A. and I didn’t know anybody who worked in the industry. I was always like, man, I wish I could do that one day maybe, but I didn’t know how. The only reason I started working in TV is because a guy reached out to me who’d read some of my journalism and asked me if I would come work on his TV show.

COOGLER: Who was he?

JEFFERSON: A guy named Mike O’Malley. The show was called Survivor’s Remorse.

COOGLER: LeBron’s show.

JEFFERSON: Exactly. That’s the only way I got into TV. Otherwise, I don’t know if I’d be here right now.

COOGLER: Did Ludwig do the music for it?

JEFFERSON: Who?

COOGLER: Ludwig Göransson [the composer who scored Coogler’s Black Panther movies]?

JEFFERSON: He may have, yeah.

COOGLER: That’s what’s up, man. So, you were doing journalism.

JEFFERSON: Yeah. I thought I’d go to law school or get my master’s in journalism. I just never felt like I could do it. I think that’s why I’m interested in people like you who knew from a young age that they’re going to do this.

COOGLER: It wasn’t really like that for me. I feel like I didn’t know.

JEFFERSON: Really? When did you decide that you wanted to be a filmmaker?

COOGLER: Probably 19.

JEFFERSON: Did you start at USC?

COOGLER: No, I was a football player, bro. I went to Sacramento State. I was on a football scholarship there, so I got to it weirdly. And at 19, I didn’t feel young, because in football years, 19 is middle-aged. I had a teacher read something that I wrote and he was like, “Hey, you should write screenplays.” I would do it on the side while I was doing my regular major. But it was also having to put down football, having to reckon with it. Because once I decided I wanted to do movies, I knew I wanted to do them right away. So, I had to stop playing football.

JEFFERSON: Got it.

COOGLER: I got done playing my last college game and got accepted to film school while I was finishing that season.

JEFFERSON: I really wish I would have tried this earlier, because I’m 41 now and I finally found the thing that I love to do. It took me a long time to get here, and I want to keep writing fiction and screenplays, but writing and directing this movie was the culmination of all these things that I love. But what if I had started when I was 19? Would I be better at this? Down that path lies madness, because if I made a movie when I was 21 it would have been terrible and people wouldn’t have let me direct again.

COOGLER: Yeah, bro. This movie’s great.

JEFFERSON: Thank you.

COOGLER: It feels like the type of movie that doesn’t get made anymore, which makes it so much more special.

JEFFERSON: Thanks.

COOGLER: Bro, I’m not a journalist. This is my second interview today. I just got done interviewing Jordan [Peele].

JEFFERSON: Oh, really? Amazing!

COOGLER: Yeah. One thing he was talking about was timing. When Get Out came out the timing of it was incredibly advantageous. I feel like that about this movie.

JEFFERSON: Absolutely.

COOGLER: It’s a movie for grown-ups, when those aren’t really getting made anymore. I’m thrilled that it’s coming out in theaters. Having seen it in a theater full of grown-ups, it’s a very wise movie, bro.

JEFFERSON: Thanks.

COOGLER: The film is about wisdom, in a way. I found it to be about a guy that’s almost too smart for his own good. He knows it and his family knows it.

JEFFERSON: [Laughs] Absolutely.

COOGLER: What do you do with that? What do you do with an almost painful amount of knowledge that’s keeping him from enjoying life? It had that energy to it that only cinema can hold. You can’t put that in an article or a book. Only cinema can hold that feeling.

JEFFERSON: Yeah. When I watch the movie, I see a lot of anger. I had this therapist who said this thing that I think about all the time, which is, “Anger is not a real emotion. Anger is a secondary emotion, particularly as it pertains to men, because anger is either fear or pain.” Specifically for men who have a hard time saying, “You hurt my feelings,” or, “I’m afraid.” Instead, what they do is lash out and scream and fight and break things. I started thinking about that as it pertains to my life, and I was like, “Holy shit, that’s true.” Every time I find myself getting angry these days, I always try to stop and think, “Okay, what’s the actual emotion?”

COOGLER: Right.

JEFFERSON: With the Monk character, there’s a lot of pain there. He’s hurting a lot, and the way that he’s channeling that hurt is through rage and making all these bad decisions, alienating his family and alienating his romantic partners and just pushing everyone away. And so, I think that’s a very astute observation.

COOGLER: It sounds like a brilliant observation by your therapist.

JEFFERSON: Yeah. I think for men, and especially men of color, there’s a lot of anger. James Baldwin’s one of my literary heroes, and he says that, “If you are Black in America and you’re at all paying attention, then you are in a state of constant anger.” I’m paraphrasing, but that’s essentially his quote. And so, I feel angry all the time about any number of things. It took me a long time to figure out healthy ways to channel that anger, so when I see this movie, I see so much of my anger in the film, and so much of it is not just professional anger, it’s also personal anger. A lot of the rage that is swirling in my head at any one time is in the movie. I think it comes across to people like me, but there’s other people who’ve watched the film and they’re like, “I actually don’t see anger. I see hurt.”

COOGLER: Yeah, it’s interesting, bro. I think it’s a brilliant performance by Jeffrey [Wright]. I don’t want to put any spoilers in it, but some of Jeffrey’s reactions to some of the things he sees, and a lot of it is absurd, are passive-aggressive observations.

JEFFERSON: [Laughs] Exactly.

COOGLER: Because sure, somebody could say it’s an angry Black intellectual movie, but it’s also a movie about a guy who’s passive-aggressive.

JEFFERSON: He’s an asshole.

COOGLER: Yeah. Constantly.

JEFFERSON: [Laughs] But in a way that’s charming, because you understand why he’s being this way. You see his side of it. The great thing about Jeffrey’s performance is, if you have the wrong actor there, people would be like, “Well, fuck this guy. I hate him.”

COOGLER: You’re dead in the water.

JEFFERSON: It takes somebody who can give you the grumpy, cantankerous energy, but also somebody that you’re like, “But I want to give this dude a hug.” That’s a difficult needle to thread and I think he threaded it well.

COOGLER: I remember at the festival you mentioned that you were reading it in his voice.

JEFFERSON: I thought of him when I was reading the novel, and I started reading the character of Monk in Jeffrey’s voice. When I was picturing the scenes, I was picturing Jeffrey.

COOGLER: When did you first come across the novel, bro?

JEFFERSON: December of 2020. It came out in 2001. I was reading this review for another book, and in the review it said that this other novel had satire reminiscent of Percival Everett’s Erasure. I’d never heard of Erasure. I went out and bought the book and just plowed through it.

COOGLER: Had you always been a reader?

JEFFERSON: I had. My mother told me years ago that she knew I was going to be a writer when I was in third grade. She was like, “You always loved to read,” and then in third grade I got an assignment where we had to write our own books, and she said, “I’ve never seen you more excited for a school project than writing a book and illustrating and binding it yourself.”

COOGLER: When did she share that with you?

JEFFERSON: When I got out of college and started dabbling in journalism. Because when I graduated college, I had a day job as a communications coordinator at this nonprofit in Venice Beach. The goal of the nonprofit was a righteous one and I supported the mission, but I hated the work. It wasn’t creatively fulfilling. I didn’t necessarily like the people who were running the operation. So, I would come home and be miserable, and I would write on the side. I started dabbling in freelance journalism, and my parents saw how excited it made me. Then I quit my day job after a year and started freelance journalism full-time. That’s when my mom said, “It just took you forever to realize that you were going to be a writer, but I knew that you were always going to be a writer.”

COOGLER: She was holding that.

JEFFERSON: You realize that your parents just know you. I thought that I was always keeping it close to the vest that I wanted to be an artist one day. I didn’t think it was obvious. But she knew me deeper than anybody knew me. She saw me even when I didn’t see myself.

COOGLER: That’s my experience, bro. You’ve never watched anything like you watch your kids. So of course they know. Being on the other side of it now, I’m watching everything about them.

JEFFERSON: You see everything about their personalities.

COOGLER: Yeah. I’m afraid there will come a time when they will hide things. But third grade, forget about it. Where did you go to school? Run it back for me.

JEFFERSON: I went to college in Virginia and didn’t like my college experience, if I’m being honest.

COOGLER: What part of Virginia?

JEFFERSON: Williamsburg. It’s [William & Mary], the second-oldest school in America after Harvard. My dad was the first Black law student who went to William & Mary Law School.

COOGLER: Holy shit, bro.

JEFFERSON: The Black Law Student Association was named after my dad, so there’s a history there, and my dad really wanted me to go. As soon as I got there, I was like, “Maybe this was the wrong decision.” I got a great education, but I felt like I was missing a lot, culturally. I felt very much like an outsider. I’d never lived in the South, which is—

COOGLER: A different vibe.

JEFFERSON: A different vibe entirely. I had never seen somebody who played lacrosse.

COOGLER: You’d never seen the sport?

JEFFERSON: No. So there’s these dudes with swoopy hair and polo shirts and khaki shorts, groups of people that I’ve never seen before. I had all these friends who were going to school in New York and San Francisco, having all these interesting cultural experiences and growing. In high school I was really involved in stuff, but then I got to college and it all fell off. I was super depressed.

COOGLER: Sorry about that.

JEFFERSON: I didn’t go to class, I didn’t do any work, I was drifting.

COOGLER: That’s tough, bro. Did you ever get hints that maybe art was for you while you was in high school?

JEFFERSON: When I was in AP English in my junior year we had to write a couple poems and then you had to come and read your poem in front of the class. I remember reading my poem and my friend came up to me afterward and said, “The poem’s good.” I lied and said that my older brother helped me write it because I thought it was embarrassing to be good at writing poems.

COOGLER: Right.

JEFFERSON: So I lied and said my brother helped me because I felt like it was shameful.

COOGLER: To be a good poet.

JEFFERSON: Well, not even to be good, but to put effort into it. I thought it was shameful to say, “I went home and really worked hard on this poem.” That felt embarrassing to me.

COOGLER: Where do you think that comes from? Was it an identity thing? Did you identify as a jock?

JEFFERSON: No, but I think that I was raised by a father who was very emotionally unavailable and distant. He was always present, but my dad’s a Vietnam veteran. He went through some heavy shit when he was younger. He was born in the ’40s and I think a lot of men in that generation didn’t talk about their feelings.

COOGLER: It wasn’t a thing.

JEFFERSON: Exactly. My dad came back with a lot of PTSD, and he never talked about it. Always around, but very emotionally distant. So, to me, things like vulnerability and poems and sharing your emotions in this artistic way was—

COOGLER: Not a thing men do.

JEFFERSON: It’s weak. Being in touch with your emotions and being emotionally available was not something men did.

COOGLER: Fully internalized.

JEFFERSON: Oh, yeah. That’s until very recently. That’s the thing, man. So much of me is in that movie.

COOGLER: That’s what I’m saying. It’s so many moments like that in the film, bro.

JEFFERSON: Exactly. I have a question for you that pertains to what we were just talking about. Because it’s interesting to me that you come from a football background, I think just as masculine and chest-thumpy as what I’m talking about. Was it weird for you—

COOGLER: To want to be an artist?

JEFFERSON: Yeah, in this world of super masculine energy.

COOGLER: It’s so funny that you asked that because I’m from the Bay Area, bro. What we’re good at culturally is holding diametrically opposed ideas at the same time. It’s something that’s oddly socially acceptable there. I have never been in another place like that. I have an older cousin who’s an actor now, and he was the best football player that I knew at the time. Just an incredibly tough guy, a running back. He could fight real good. He’s a lighter-skinned guy, so he fought a lot.

JEFFERSON: [Laughs]

COOGLER: And he wrote poetry and would brag about it. He would say, “Yo, I’m writing this poem, man,” and he would almost dare somebody to say something. Even Tupac, we kind of claim him in the Bay Area, even though a lot of places could claim him. [MC] Hammer, even. Long known as being the first pop rapper, but he was also a dude who was known in the streets. So, it’s an odd place where I do still to this day have a little bit of discomfort thinking of myself as an artist, but it’s not about masculinity or toughness. It’s something else, bro. I think it’s not thinking I’m good enough to be able to be considered.

JEFFERSON: Impostor syndrome.

COOGLER: I think it’s something worse because I struggle with impostor syndrome, too.

JEFFERSON: Me too.

COOGLER: It’s something I have to do some therapy to unpack. You know what I’m saying?

JEFFERSON: Yeah.

COOGLER: Still to this day, I feel like I’m fronting if I say I’m an artist.

JEFFERSON: Really?

COOGLER: Yeah, truly.

JEFFERSON: Man, me too. I’m so happy we’re having this conversation. I have impostor syndrome deeply and I don’t know if I’m ever going to get over it. People keep asking, “How’s it feel that the film’s successful and it’s getting great reviews?” And I just feel so overwhelmed. I think part of the reason I feel overwhelmed is because, for whatever reason, this feels wrong for me.

COOGLER: You find yourself waiting for somebody to tell the truth.

JEFFERSON: Exactly.

COOGLER: You don’t believe that the good thing—the good news is not the truth. It’s the danger of this business, honestly.

JEFFERSON: Well, I think that it’s also, the higher you climb, the less people look like you in the rooms. I think that’s part of it.

COOGLER: Totally. It burns, almost.

JEFFERSON: Exactly.

COOGLER: Look, bro, I could tell you objectively, I don’t know you, but the movie’s great. And it’s great in ways that are repeatable, if that makes sense. It doesn’t feel like a fluke, which is I think the best compliment I could give you.

JEFFERSON: It means a lot to me.

COOGLER: I think it’s a part of your body that’s naturally trying to reckon with the onslaught of good things that’s about to come your way in the coming months. And a part of your body naturally is going to disassociate a little bit just to survive. That’s okay, but as best as you can be, be present. It’s a time for you to surround yourself with people who loved you before, who are going to love you no matter how the movie turned out. Lean into those relationships as best you can.

JEFFERSON: Yeah, man.

COOGLER: Keep them around you to help you discern things that’s coming your way, if you can. But yeah, bro, it’s a great film at a time when the world needs it.

JEFFERSON: Thank you.

COOGLER: So, the world is going react dramatically to it, I think.

JEFFERSON: Thank you.

COOGLER: And that’s fine. I think that’s okay.

———

Grooming: Sonia Lee using Kevin Murphy at Exclusive Artists.

Production Manager: Christina Najar

Location: Mother Wolf.