THESPIAN

Clarence Maclin Tells Jon Bernthal How Prison Led to His Second Act

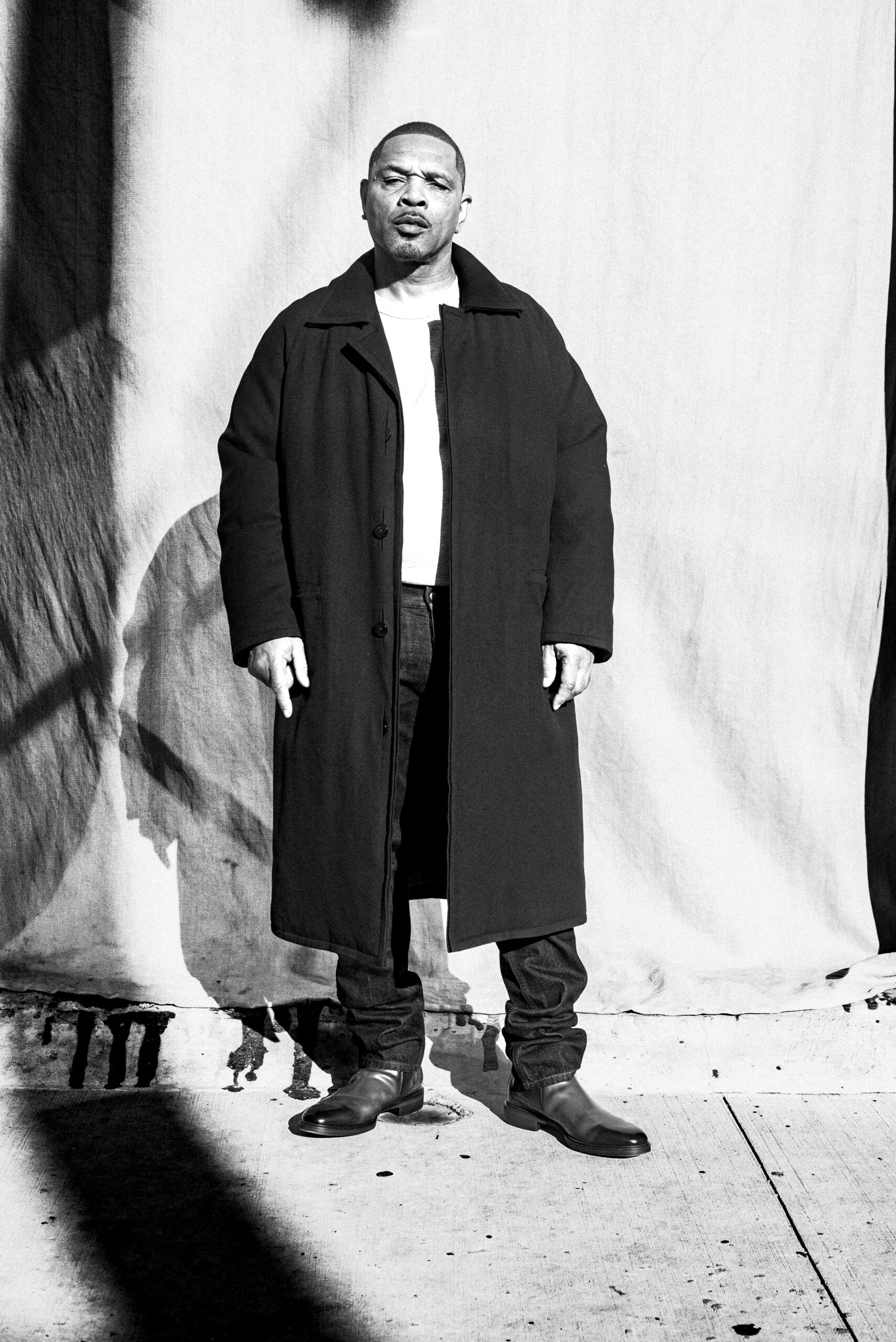

Clarence Maclin wears Jacket Zegna. T-Shirt Hermès. Pants Willy Chavarria.

Clarence Maclin wasn’t supposed to be here. After serving 17 years in Sing Sing, he transformed his life through the prison’s Rehabilitation Through the Arts program, where men who are incarcerated collaborated to write, direct, and perform original plays. That experience—of creating something meaningful within the confines of prison—comes full circle in Sing Sing, a film inspired by the program. Co-starring Colman Domingo and directed by Greg Kwedar, the A24 movie has become a critical darling, and, with a theatrical re-release this month, an awards contender, lauded for its raw, humanizing portrayal of redemption through art. Maclin’s performance, which earned him a Gotham Award for Outstanding Supporting Performance, is nothing short of astonishing—layered, intimate, and so authentic it feels like nothing else on screen this year. One person especially moved by it was the actor Jon Bernthal, who connected with Maclin to talk about finding freedom on stage, redefining masculinity, and the power of second chances.

———

JON BERNTHAL: Oh, that “recording in progress” makes my pookie get tight. [Laughs] I want to just say it again because it’s recorded now, how much of an honor this is for me, man.

CLARENCE MACLIN: Likewise, bro. I really enjoy your work.

BERNTHAL: What you did in Sing Sing is so special, and I can’t begin to tell you how much it meant to me, personally, on many different levels. Where are you right now?

MACLIN: Harlem, New York.

BERNTHAL: That’s what’s up. Now, I have to give you a little warning. There are about 25 kids in this house right now, because I’m in a small-ass house and these kids are wild, so you never know what’s going to happen.

MACLIN: [Laughs] I get it.

BERNTHAL: There might be screaming and crying and punching, but everything’s good, you know what I’m saying?

MACLIN: That’s a beautiful thing.

BERNTHAL: I guess I want to start off by asking you, do you look at your life and see an old Clarence and a new Clarence? And if so, how would you define the two?

MACLIN: I think I look at myself as an evolved Clarence. I don’t think the old guy went anywhere. He’s still in there somewhere. Elements of everything I’ve ever been are still here, like in everybody else. It’s just, how do we utilize those past experiences for a better future experience? How do we utilize those memories, the things that we went through and the experiences that we’ve had, the trials and tribulations, the pros and the cons? I think that’s what differentiates knowledge from wisdom. Wisdom is applied information.

BERNTHAL: So, not to ignore or say that this ain’t a part of me anymore, but to take that same thing that might’ve once caused me to go down one path, and to get into something else.

MACLIN: Right. Use that and redirect it.

BERNTHAL: How did theater or acting become a conduit for that? Is it the perfect tool to funnel those things?

MACLIN: That’s exactly what it is for me, because you get to pour so much into a particular message, a particular story. It’s like the potter’s wheel, you know what I mean? You get to shape this thing. You get to create and craft it so that when it’s dried and hardened, you present it, because the creation is never for the creator.

BERNTHAL: Yeah. When I was a young man, I ran into a lot of walls and got myself in a lot of dead ends. And I’ve often found that the same energy that caused me to wild out and cause pain in other people’s lives, I can apply that same fire to this, and it actually brings me closer to people. I’m wondering if that’s the experience that you had, and was there a specific time when you realized it?

MACLIN: Yeah, that happened when I got involved with Rehabilitation Through the Arts. It was like a light switch went off, because I was once an artistic kid. I used to always draw, paint, create with my hands and things of that nature. However, I suppressed that part of my life to be with the in crowd, because the painting, the drawing, was kind of nerdy. Trying to fit in is what really took me away from that creative me. Reconnecting with that when I got involved with Rehabilitation Through the Art and starting to see that we had a platform, where we can do this in prison, was like the silver lining in that cloud.

Jacket Zegna.

BERNTHAL: Were you suspicious at first?

MACLIN: Yes.

BERNTHAL: What made you a believer?

MACLIN: Seeing my brothers up there doing it. Brothers that I knew from different portions of the jail, different places, different circumstances. I didn’t know them for this, being on stage and delivering a message. And I’m feeling the energy of the audience and how they’re gravitating towards it, and I’m caught up in that. So that right there is when the artistic thing in me turns back on. So I got to find a way to be a part of this, man. How do I sign up? But signing up was kind of like a roadblock because firstly, I had no faith in prison programs. To me, it seemed like it was a bunch of people from the other side of the wall that wanted to come in here and act like now that they did something for a prisoner, they could sleep at night, or get a tax break. But when I seen the bros up there and the art that they were creating, it made me want to be a part of that thing. But getting into the program was kind of difficult because you got to not have any infractions and stay out of trouble for at least a year. Now, I was trouble-prone in prison. I had trouble every day. That’s what’s going on. I had to take a whole year, and I did it. After that year, I didn’t really want to get in trouble anymore because I’ve been walking this way for so long now and it was cool. I’m good.

BERNTHAL: Yeah.

MACLIN: There’s no need to go backwards, you know what I mean? So I got in the program and then somebody was putting on a production called Stratford’s Decision, a play that was written by prisoners. And when I got in, I was only able to be a stagehand, but somebody in the cast had dropped out for whatever reason, and it opened up the slot. So they slid me in there. Now, I didn’t have any lines, so I’m up on stage posturing.

BERNTHAL: We’ve all been there.

MACLIN: I got a whole dialogue in my head, but no lines. However, the director, I guess he believed I postured really well, so he gave me two lines. After that, I was bitten. The next production, I’m like, “Yo, listen, I need a lead role.” I fell in love with it. I fell in love with Shakespeare, I fell in love with Sophocles. I fell in love with all these ancient playwrights that I don’t know how I hear them, but I hear them.

BERNTHAL: You hear them, you feel them. Talk to me about courage and bravery, and how you define those things. Sometimes the arts are looked at as soft or whatever, but when you really do them and you really lay your life on the line for it, you realize it takes a level of courage. I’m just wondering if you could take me through the first time you realize how much courage it takes to get up there and be vulnerable in front of other people?

MACLIN: Listen, in this society, we grew up thinking that manhood means to be tough, to be rude, to be oppressive. I don’t know where we get this from, but we associate these things with manhood.

BERNTHAL: Yeah, closed off and hard.

MACLIN: Men don’t cry. You know what I mean? Those types of ideologies seep into our character and begin to define us. One of the things that Colman [Domingo] brought to us was the way that we could be more gentle and in touch with one another, to be able to say, “Bro, how you doing? You having a good day?” In prison that’s something that men don’t do. We want to break that. We want to show the difference between that type of masculinity, and the nurturing kind.

BERNTHAL: That takes courage, man. I don’t think I’ve seen a film or even a performance that’s been articulated as honestly as what you all did. The seriousness of your group sessions and how sacred it was, I wonder how the old me would look at that. I remember when I first encountered that, I was like, “These are the weirdest people I ever seen. Why is everybody taking this so seriously?”

MACLIN: Exactly.

BERNTHAL: Now it’s like, no, we owe our life to this. This saved my life. And I think in this setting, what really spoke to me was, man, these folks are free. They find their freedom through that. It’s so vital to all you, and you guys really captured that. That’s a more elevated stage of manhood for sure.

MACLIN: Yes, it is. Once you realize exactly what the potential that you have to make change in not only yourself, but affect others around you, you could take the mask off and just be you in there. And that space became sacred to everybody involved, because once we stepped in that space, we’re no longer prisoners. We’re free. I done been to Greece, Africa, all over the world, right from a prison cell, bro. I was sitting in a prison cell and went everywhere. That’s what art does.

Coat Zegna. T-Shirt Buck Mason. Jeans Hermès. Boots Santoni.

BERNTHAL: That’s right. I often say that to young kids that I work with, or my own children: Focus on the things that no one can take away from you, and that’s it. Like you imagination, your heart, those kinds of things.

MACLIN: Yeah, man. That was the intent, to bring us back to the reason why this thing called theater was created. The reason was for healing. Because there was no TV, no internet, none of that. You had to come to the theater to get your news, your gossip, everything. In those ancient theaters is where the populace learned that you’re not the only one going through whatever it is you’re going through.

BERNTHAL: When they came to you and said they want to make a film on this, how did that feel to you? How did it feel to go back into Sing Sing?

MACLIN: Well, it’s a little apprehensive. Others have come to our RTA program with the same appeal. They want to tell our stories. However, when we sit down and talk to the individuals, we notice that they want to make changes with this and changes with that. And that takes away from the message and the integrity of the program. Like we said, we created a safe space, which was sacred to us. So this program is that we don’t want nobody to mess it up. Not even me. I don’t want to be the one to mess it up. So when we met with Greg and Clint, the filmmakers, we got to immediately know that they were genuine, and we learned that through conversation. Not even talking about scripts, not talking about movies, not talking about the magazine that they had found us in. They found us in the Esquire magazine where they had researched the play Breaking the Mummy’s Code, and they got in touch with Brent, Brent Buell, who’s played by Paul Raci. They got in touch with him and he told them that if you really want to know the story, you should talk to the men that lived it. So this is how the meeting came about. So he’s sitting around and we’re just talking about everything, about how do you see the world, what kind of human being are you? And while we’re feeling them out, they’re feeling us out at the same time. So it was really a no brainer. Once the bond was made, that the integrity of the program and integrity of the story is what’s most important to us, it was a no brainer.

BERNTHAL: And so many people are going to be reached by this. I know you do a lot of outreach, community service, and I can tell you the strongest way to stay on a path of righteousness is to go try to help others who are still down in that valley.

MACLIN: That’s it.

BERNTHAL: And I imagine through this film, you’re going to do that, not just with folks who are incarcerated, but in general. What does service mean to you and how has that been a guiding light?

MACLIN: Well, service has always been the guiding light because, once again, these are the skills that we learned from the program that we created in prison. Giving back. It’s like going back to your own foundation and fortifying it. That’s what you get from service, from helping others. When I worked with these at-risk teens through my program, which is Successful Steps, what I learned is when you go in, you’re thinking that you’re going to help the community. You’re going to be of service. Well, what’s actually taking place? This is a two-way street. You’re going to learn something. You’re going to interact. You came to give, but you receive as well.

BERNTHAL: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Tell me about Colman, man. I know him a little bit. The few times that we’ve gotten together, I’ve really treasured it. What did you learn from him and what would you say he learned from you?

MACLIN: This is what I learned from Colman. He’s a theater guy, and Sing Sing has poor acoustics, so I had to project, come all the way from the diaphragm every time. Even the whispers have to be projected. Colman showed me how to bring that thing right in here. You don’t have to project it out so loudly. We got microphones. We just focus it. He showed me that. What I think Colman got from me, he’s from North Philly, but during the course of him being nice and kind and all that, he lost a little bit of that edge. I think he got it back now. [Laughs]

BERNTHAL: I love it, man. I read that with RTA, the recidivism was at 3 percemt of people that went through that program, compared to—

MACLIN: That’s a fact. The national percentage is 60 percent of those who leave prison are back within three years. With Rehabilitation Through the Arts, it’s less than 3 percent.

BERNTHAL: Why do you think that is?

MACLIN: Once you learn how to live right, it’s kind of hard to go backwards and live wrong. It don’t compute. It’s also due to the network system that we’ve developed with each other outside of prison, not only with the formerly incarcerated, but also with our volunteers. We got a network that looks out for one another when we come home. What this movie also wanted to do was shine a light on a portion of the population in prison that rarely gets the light shined on them. They always talk about eithe violence part of prison or the corrupt police that’s in prison. Now, we are not saying that that doesn’t happen, and those people don’t exist. I’m not saying that. I’m just saying that’s not the only thing going on. In every prison, I believe, there’s always a portion of the population that are genuinely interested in bettering themselves.

BERNTHAL: I have a dear friend, some folks I work out with in California. My friend Brett Mays, a life without parole, LWOP prisoner down in Calipatria [State Prison]. And they have a group of people, this LWOP community, and they get together and they do these writing seminars, and they get together and they cross all the racial lines. And very similarly, what I found with these guys, it’s like you said, I think once you evolve, it is very hard to go back. I love what you said, just to shine a light on these people doing this beautiful work, getting better and better and better behind those walls. We need to remember that, we need to honor it, and we need to support it.

MACLIN: Yep, definitely. That’s what this is about. Because listen, 90 percent of the people in prison are coming home. Who do you want in the laundromat with you? Who do you want in the grocery store line with you? Who do you want picking up their kids from the same school your kids are at? Do you want somebody who just went to prison and did nothing, just stayed in there for 10 years, kicking a rock around the yard? Or do you want somebody to come home who actually took the time to pour something into themselves? These are the questions I ask when people wonder why our tax dollars are paying for this? Why are the prisoners getting to go to college? What else do you want me to do with this time? You want me to come home angry and bitter? Or would you like me to come home educated and prepared to add onto the world?

BERNTHAL: That’s beautiful, man. Well, look, I appreciate the time. And again, I’m filled with gratitude for you and your performance and your model. You’re the kind of man I want my kids to see and learn from, and that’s sacred to me, bro.

MACLIN: Oh man, thanks.

BERNTHAL: And bless you and bless your family. I look forward to meeting you in person and shaking your hand.

MACLIN: Me too, bro. Enjoy the rest of your day and bless the babies, man.

BERNTHAL: Always.

Coat Zegna.

All Clothing Diesel. Sunglasses Zegna.

———

Grooming: Marcos “Reggae” Smith.