Chloé Zhao and Alfonso Cuarón on the Quiet Compassion of Making a Movie

There are brief moments sprinkled throughout Nomadland where it feels as if you’re watching a documentary—a critique of Amazon’s grip on American industry, perhaps, or a verité look at the country’s vast network of RV parks. But then Frances McDormand reappears, and you’re reminded that this naturalistic film from the director Chloé Zhao is, in fact, a work of heartbreaking fiction. Adapted from the real-life findings of Jessica Bruder in her 2017 book of the same name, Nomadland is set in the American West, among an older segment of the population who, in the wake of the Great Recession, have chosen to leave the grid, drifting from place to place in search of work. “I’m not homeless, I’m just houseless,” is how McDormand’s character, a widow named Fern who lives in her van, puts it early on. Nomadland is a road movie without a destination.

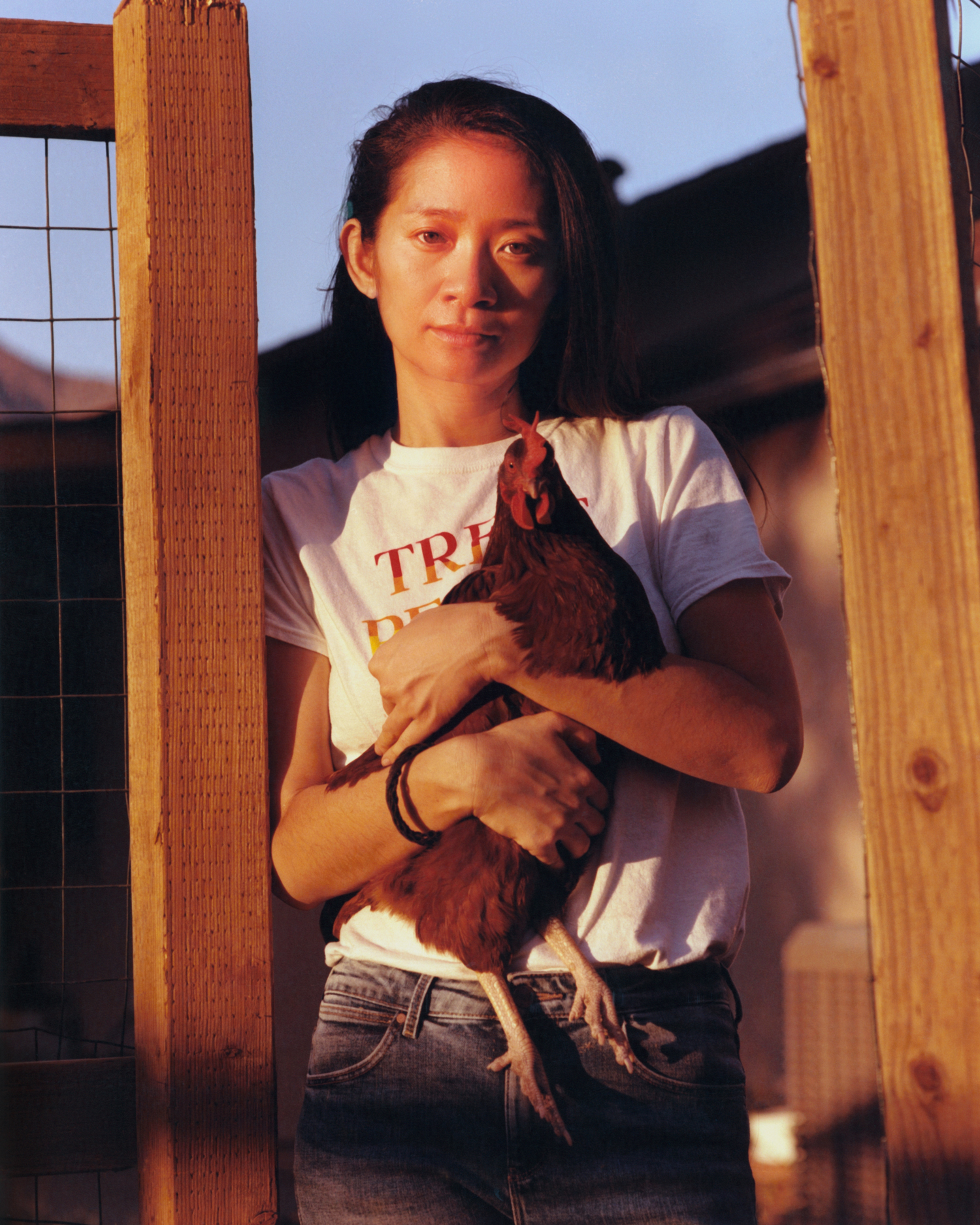

It is also Zhao’s third feature, after 2015’s Songs My Brothers Taught Me and 2017’s The Rider, an aching rodeo drama that won the 38-year-old filmmaker universal acclaim. As with those movies, Nomadland relies heavily on untrained actors playing versions of themselves to steep the story in a sense of community, lending it a richness that even the world’s best casting directors would struggle to match. It also establishes the Beijing-born director as a vital chronicler of the American heartland—part journalist, part voyeur, all poet. Zhao’s next film, the Marvel space saga Eternals, starring Angelina Jolie and Richard Madden, marks a leap so dramatic that it made even the five-time Oscar-winning director Alfonso Cuarón’s head spin. —BEN BARNA

———

ALFONSO CUARÓN: I was finally able to watch your film and I was completely unprepared for it. You took me on this amazing journey in a world that I’ve never been to before. I love films where I cannot fully understand the process, because that’s where I find the mystery resides. Let’s start from the moment of conception.

CHLOÉ ZHAO: When I was making Songs My Brothers Taught Me and The Rider, I did a lot of traveling, so there was definitely a desire to make a road movie. After The Rider had come out, Frances McDormand and her producing partner, who had acquired the rights to the book Nomadland, called me up and we met, and that’s kind of how the seed was planted.

CUARÓN: What was the scripting process like?

ZHAO: The book is nonfiction, and the character Fern doesn’t exist in it. But the writer [Jessica Bruder] introduced me to Quartzsite, Arizona, where the gathering of the nomads took place. Characters like Swankie, Linda May, and Bob Wells are all in the book. I did a lot of research for Songs and The Rider, but a lot of that work was already done for me with the book. My job was to create a fictional character whose emotional journey could organically incorporate some of the interesting things that are in the book.

CUARÓN: It’s clear that the screenplay has a structure. How much of each scene is scripted, and how much is stuff that you’re finding in the moment?

ZHAO: We had about a 90-page script, and it’s pretty much the movie, in terms of what’s supposed to happen within each scene. But, for example, when I met Swankie, one of the first things she showed me was the video of the swallows, and the story of her traveling and kayaking through America. I wrote that story into the script. By the time we were shooting the scene, I’d already written what she was going to say into the script. She might have gone off script a little bit here and there, but we were mostly following it.

CUARÓN: You were born in Beijing, then you studied in London, then you went to NYU, and now you live in California. How do you explain your fascination with the middle of America?

ZHAO: It’s really hard to explain, but I can rationalize it if I dig a little deeper. Growing up in Beijing, I always loved going to Mongolia. From the big city to the plains, that was my childhood. Spending a lot of time in New York in my mid-20s, I was feeling a bit lost. I always joke that historically, when you feel lost, you go west. And for me, going west is west of New York. It’s just a part of America that I don’t think I knew anything about. South Dakota, for example, is mostly a ranching state. The dirt on the ground hasn’t been touched. It feels ancient and static. And my life has been so transient and fast-moving that it’s just such a nice feeling when I’m there, almost like time stops.

CUARÓN: The beautiful thing that you do with your films is that you partake of them. You partake of their experience. In other words, it’s an act of compassion. You’re not objectifying your characters— you’re actually seeing them. And because of that, there’s a closeness to all of these characters. The film is filled with social commentary, but it doesn’t become a pounding political statement. You just allow it to flow, because your focus is on the humanity of these characters, without any judgment. It’s as if you’re just partaking in their existence. I think it’s something very special.

ZHAO: Well, thank you. But just by pointing the camera at something, you’re already making a statement of some kind. It’s inevitable, because you’re adding a perspective to it. I find that sometimes when I go into a community that’s not my own, or a community that has a lot of issues attached to it, I have to resist wanting to say something about how I think they could be better, or how I think the government has wronged them. A lot of times, they tell me what they think I want to hear because they’ve been interviewed many times by journalists. And usually, there’s something that these people who are interviewing them want them to say, because people go in with an agenda. I hear them saying things to me almost like they’re programmed to do it. You have to wait for that to be finished, and then you can ask, “What football team do you support?” or, “Tell me about your high school sweetheart.”

CUARÓN: That is really impressive, because in this day and age, in which everything is polarized and filled with ideology, there’s not one single discussion like that in the film. Maybe when Fern questions her sister’s friends about real estate, but the whole point of that is not to make a political statement about our economic system, but to make a statement about her position in terms of her life choices.

ZHAO: Making films is about communicating, and I am terrified that I will end up making films for people who already agree with me, which just keeps enforcing our own ideas. I’d rather have one person who disagrees with my politics watch my film, and then somehow see themselves in it without putting up a shield, than a whole room of people who already agree with me give me a standing ovation.

CUARÓN: You cannot predict what audiences are going to like. And if you do, they won’t be surprised. And that’s the beautiful thing about your film. What I don’t understand is how you were shooting Nomadland and at the same time prepping a big Marvel film.

ZHAO: You go from smaller movies to big movies.

CUARÓN: But I don’t film one while prepping the other. I’m too lazy.

ZHAO: I wasn’t really prepping Eternals when I was shooting Nomadland, because that wouldn’t be possible. But we had gaps in between, so I was able to do a little bit of prep. When I finished Nomadland, I jumped into Eternals full time. I actually found it quite healthy for me to be able to juggle the two of them. They’re so incredibly different that I got to escape from one to the other when I needed to.

CUARÓN: It’s so easy to make films that question and criticize and show all the wrong things that we do as humans, but this is a film about kindness. Another thing about Nomadland is your collaboration with your cinematographer Josh [Joshua James Richards]. It’s very telepathic between the two of you.

ZHAO: That’s partially because he has sat with me in the editing process for all three films. I always do the first cut, so he understands how I want to edit the footage. I don’t need to tell him how to cover it because a lot of times he knows where I’m going to cut. That’s probably why we have a shorthand.

CUARÓN: Let’s talk about Frances. We’ve always known that Frances is a miracle on this earth, but this performance is a miracle among miracles. She’s Fern in every single instance. You don’t know which one is a professional actor and which one is not, who’s a real nomad and who’s an actor. She’s just there. You wrote the screenplay and then approached her?

ZHAO: When we met, there was no screenplay. Initially, the thought was to have Frances play Linda May. Once Frances saw The Rider and we met, we thought Linda May needed to play Linda May, and Frances was going to play a fictional character that would bring all these people together. We really wanted Frances to be a part of Fern, as well. Even the name. As soon as we met, Frances said to me, “I always thought when I turned 65 that I was going to change my name to Fern, start smoking Lucky Strikes and drinking Wild Turkey, and hit the road in an RV. That’s my dream.” There’s a lot of her life that she so generously allowed us to have in this movie. Even Melissa Smith, who played Fern’s sister, is Frances’s best friend in real life.

CUARÓN: In a film as quiet as yours, in the sense that it’s not pumping out plot twists or huge moments, for her to have that confidence and faith in her character is very courageous. In a contemporary world in which dramatic gestures are rewarded, she just allowed her character to flow with the same kind of gentleness and quietness as the rest of the environment and the people around her. It’s really remarkable.

ZHAO: And really, really hard to do. Like you said, louder and bigger is often awarded, but that’s just not how life is. Especially being on the road, having seen what life is like for people of that generation, it’s not about deadlines or dramatic twists and turns. It’s more about the transience of life, the feeling of being a part of the ebb and flow of nature, everything being where it’s supposed to be. It was so important for us to make sure that Fern’s journey isn’t one of plot twists, but an internal journey through time.

CUARÓN: A lot of actors would want to try to spell out what they’re feeling with important monologues.

ZHAO: An incredible moment that taught me so much was at the garage when her car broke down. She went to see these mechanics, and I wrote a scene in which she would get very upset with the mechanic because he’s suggesting that she should sell her van. But we got to the car shop, and the mechanic was in fact one of the sweetest men I’d ever met. All he loves to do is fix people’s cars, because he feels like out there in Nebraska, your car is your life. He said, “People often come to me and feel like their life has ended when their car breaks down, and I love to help them.” Frances is such an incredible actor and human being that she, in the moment, was deeply present and connected to him. She just wouldn’t let herself go there, to the kind of forced script, because she was truly connecting with him. As a result, her performance changed in a way that made it so much better.

CUARÓN: There’s a lot of confidence in the film that you were making.

ZHAO: Deep inside, we’re all scared shitless.

CUARÓN: [Laughs] I’m sure.

ZHAO: On the day of the premiere, we were like, “Do we have a movie?” You have to trust the audience as well. I think a lot of people will probably fall asleep, but those who don’t might just have a different experience.

———

Hair: Richard Collins at TMG-LA.com