IN CONVERSATION

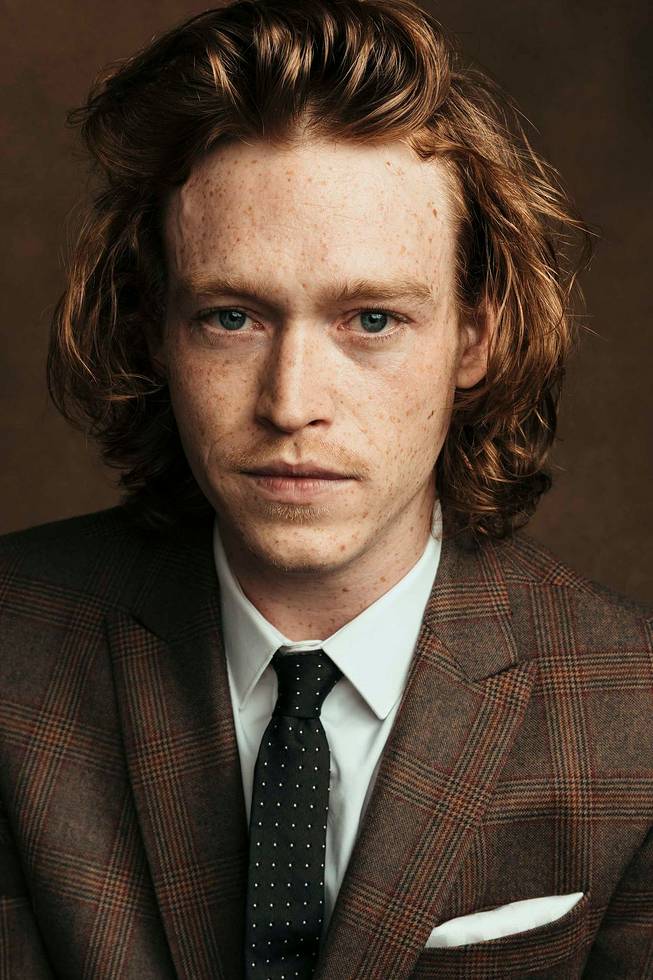

Caleb Landry Jones and Christoph Waltz Got That Dog in Them

Caleb Landry Jones has become a master of portraying the angry and sensitive young man, a cinematic archetype that often unravels into heinous acts of violence. His performance in Luc Besson’s new film DogMan offers the same damaged, off-kilter intensity, playing out in a fever dream of a script. Jones plays the film’s traumatized anti-hero—the Dog Man himself—who, despite being in a wheelchair, nurtures an intense psychic bond with a pack of dogs, allowing him to operate as a kind of godfather-like figure in a perilous crime-ridden landscape. He also spends much of the film in full Marilyn Monroe drag. Much like Landry’s description of Marlon Brando’s acting, DogMan is “all over the place, but there’s logic to the madness.” To unpack his process and influences, Landry sat down with Christoph Waltz, a veteran of portraying complex villains, to talk about great American leading men, True Grit, and the logistics of dog training. According to Waltz, “if you have no clue, then the dog will dominate you.”

———

CHRISTOPH WALTZ: We were having a conversation about the school of acting—

CALEB LANDRY JONES: I was reading somewhere you quoted Harrison Ford saying, “My job is not to tell you how to feel, but—”

WALTZ: Right, I’m not here to tell you how I feel about my character. I’m there to tell you how you feel about it. Isn’t that why it’s called the “actor”?

JONES: Yeah. So then I was getting all nervous about, “How do we do this [interview] and not talk about it?”

WALTZ: And it’s interesting what you just said, that you need to play a detective in order to start appreciating the finer aspects of the taste of coffee. And I say—

JONES: No, that’s sad, I think, if that’s what it takes.

WALTZ: Exactly. I say it’s the other way round.

JONES: Tell me if the smoking’s driving you nuts, too.

WALTZ: No, no. I’m grateful for every smoker.

JONES: [Laughs] That they’ll die earlier, or?

WALTZ: I quit, but the militant policing of smokers is crazy.

JONES: I heard they’re taking away outside smoking in Paris. I thought they’ll never let that happen.

WALTZ: I meant to ask you about the dogs, because I am seriously interested in the behavior of dogs. I think dogs are fantastic.

JONES: Two of my friends are only going to come see the movie because of the dogs.

WALTZ: Fair enough. Did the dogs get into fights while shooting?

JONES: I mean, it was so controlled that nothing serious ever happened. But that’s because they were together daily for a month beforehand, in the parks and stuff. Everyone was training together. And the dogs from the shelters fit in so quickly with the ones that were already following the leader, so to speak.

WALTZ: You know, Irish sheepdogs, border collies, they’re not trained by people. They’re trained by their mothers. It’s incredible. They know how to herd because they learn it from their mothers.

JONES: Right.

WALTZ: We learn acting in a studio with a megalomaniac teacher.

JONES: No, we learn it in school, and we’re bullied, and we’re trying to get out of it.

WALTZ: Well, that’s why you need to go to school. Not for the information, but for that.

JONES: You felt it was as easy to work with a dog [as a human]?

WALTZ: Well, it is if you know what to do. If you have no clue, then the dog will dominate you.

JONES: But that’s great too, you know? I remember there was one movie I did where there were like, 12 dogs in the movie, and one dog was turning around like an idiot, so it made sense to the character to stick my nose in his asshole. It was great, but you can’t tell the dog to turn around and say, “Hey guys, I got a great idea.” It’s better for the film and better for the character.

WALTZ: And probably for the dog, too.

JONES: The dog didn’t mind, but he’s doing the same thing to somebody else in a few seconds. They’ve got no choice but to be what they are. But I think [Marlon] Brando’s dying for these things.

WALTZ: You don’t think a dog can show off or try to impress people?

JONES: Absolutely. We had those Hollywood dogs that would assess a little bit differently because they were taught differently. The ones that were fresh would miss [a shot] and now we’ve got to explain to them that you gotta do it a few times. That’s the beauty of watching it back several times now and seeing the [editing] finesse. It’s so great working with someone that knows their film in that way. It takes such a load off the actor and the crew.

WALTZ: I totally agree. Because I think it’s bullshit that the actor will solve the day.

JONES: I think you can sometimes get a little more juice than you’re expecting from the lemon, and that’s incredible. There’s that great YouTube video behind the scenes of The Score with[Robert] De Niro and Brando doing a few takes in a row, and Brando’s just grasping at straws for anything that’s alive, anything that wasn’t his. Maybe it’s selfish for Brando to work this way.

WALTZ: And now it’s Brando’s 100th birthday.

JONES: Oh, really?

WALTZ: I read two articles and I found them both really annoying, and this posthumous sanctification—

JONES: The arrogance around it?

WALTZ: No, to make him—

JONES: An icon?

WALTZ: Yeah, a mythology. And it’s ridiculous, because he was a ham.

JONES: Yeah. Bone and blood and afraid of his dad.

WALTZ: In the beginning he was fantastic. No one had ever seen anything like it.

JONES: I was just watching The Missouri Breaks two nights ago, and I hadn’t ever seen it before. Arthur Penn is great, and you’ve got Harry Dean Stanton and Randy Quaid, who I love. But you got [Jack] Nicholson hamming it up and you got Brando hamming it up quite a bit, and the guys were going, “Nicholson really grounds it.” And I was watching him going, “He’s not grounding shit.” Brando’s just all over the place, but there’s logic to the madness. I know people say he’s “difficult” and all, but I don’t know if the folks he was working with were always ready to…

WALTZ: I don’t care about that one bit. I find it difficult to watch.

JONES: Yeah. I remember hearing you talk about Brando and going, “It’s frustrating and self-absorbed.” You’d think after a year on stage [for Streetcar] you’d have something. But then I think that created some of the frustrations that are in the film.

WALTZ: Right.

JONES: I was talking to a film director and he had two actors who just didn’t get on. I haven’t seen the film, but apparently it worked well for the film. They were raving about how well this dynamic worked, and I got to say, is it worth it?

WALTZ: Everyone claims that their idea of reality is the gauge. I refuse. I don’t measure by your gauge. I measure by mine. Which goes back to that Harrison Ford thing.

JONES: You don’t just kick a man in the balls for cinema. You know? There’s a way to make movies where you’re not being a bully. But his work is fascinating.

WALTZ: Hang on, I meant to ask you something about Dracula.

JONES: Man, your career is fascinating.

WALTZ: I am rather surprised how long it’s been.

JONES: Yeah, that’s something.

WALTZ: Time passes. That’s all there is to it. A career’s not a personal merit, so time passes on its own. And I don’t believe in the mythology of an actor’s career. It’s bullshit. I have one philosophy: “Get on with it.”

JONES: Yeah, you don’t seem to take too many things personally, or let things get to you.

WALTZ: I wonder whether dogs are so much better at all that because even though they sometimes want to impress other dogs or people, I don’t think any single dog considers a career as a whole.

JONES: No.

WALTZ: I’m referring to the career idea when the motivation is, “I owe it to my fans.”

JONES: I don’t know about you, but I see a lot of folks make choices because of how they want to be seen by their peers or the people that rejected them.

WALTZ: Which is normal.

JONES: Yeah. But at the same time, it should be the last thing you think about. You should suppress it.

WALTZ: But you can’t, because—

JONES: Yeah. John Wayne had to be John Wayne, he owed it to the people. Thank god he played the drunk in True Grit, you know?

WALTZ: Well, as a naturalized foreigner, I don’t dare to have an opinion about John Wayne. But I can appreciate it as a phenomenon. Within the historical context, whether it makes sense or not is a different question, but it becomes interesting to say, “The West is a fiction anyway.”

JONES: Yeah, but it’s different, isn’t it? All the schools and the different actors from different countries.

WALTZ: I’d love to go to Japan. There are Japanese movies that I am totally, unrestrictedly in awe of.

JONES: Yeah, I’ve been dying to go since I was a teenager. For me, it’s really just Kurosawa. And they work their asses off. It’s crazy how fast they were ripping through those movies in the ‘70s.

WALTZ: I just watched a big epic by the director Kobayashi.

JONES: I know that name, but I don’t know his work.

WALTZ: It’s called The Human Condition. And I am in awe of Pale Flower. It’s by a director by the name of Shinoda. There’s not much happening. It’s an hour-and-a-half of people sitting around on the floor gambling and there’s not a boring second in this movie. But that Kobayashi movie is really long. It’s nine hours altogether. It’s six parts.

JONES: Oh my gosh. So don’t start with that one?

WALTZ: Don’t start with that one. Because it contradicts the assumption that all acting in Japan is fantastic.

JONES: Okay.

WALTZ: Before you go into work, how long do you usually rehearse?

JONES: Three weeks was all we had, but everybody put in quite a bit of time in rehearsals, which helped out a lot. There were a few musicians that came to New York and Los Angeles, and they just met with me for two sessions. The fiddle player, he’s been on all the records here and there, but he just came and plugged in, didn’t do the sound check or anything. He was the wild card for the evening. None of the band had heard him, and suddenly he was this thing that pushed and pulled against everything else. It was just what I’ve been looking for. Same with the horn players, who had just come in the night before for a rehearsal at one of the guys’ house. It’s incredible having folks that know their instrument like they do, but are also really into playing the music.

WALTZ: I befriended Gordon Goodwin. Gordon Goodwin is a composer and he has a big band here, maybe 17 pieces. They sight-read everything, even the drummer. Incredible.

JONES: I know. And that’s not me whatsoever. When you’re talking about actors going to a school and really honing in—

WALTZ: If a script could be written like music, maybe we could do it better. The intention is clearer, the guideline is more tangible. Real musicians make it shine, and it’s the exact same piece written in all details. But the parameters would be a little clearer.

JONES: I want a bit of both. I want a bit of, “Nobody knows how to read the music, but they’re all pretending to and playing the instruments,” and then I also want that fucking orchestra [of Frank Zappa] in Vienna. I want to hear the best of the best. I love Hot Rats. And I also love what he did when it came to standing up against the censorship of music at the time.

WALTZ: Do you listen to classical music at all?

JONES: I grew up with it always in the house. But I don’t listen to much music, period.

WALTZ: There is a symphony orchestra in Dallas, and there’s an opera house in Dallas as well.

JONES: Oh, yeah. My grandparents used to play in the symphony over there.

WALTZ: Oh, what did they play?

JONES: Timpani and violin. So that’s probably why I stay away from that stuff. It’s great, but man, jazz is the real deal. My grandfather was a jazz drummer in the big band scene. And he came in when Tommy Dorsey was throwing his hissy fits. He made his living on that, and he was doing a lot of jingles out of his house in Texas, but would never come out to L.A. for The Tonight Show or anything like that. He always wanted to stay there, and my grandma just kept teaching.

WALTZ: What did she teach?

JONES: She’d teach violin and piano. Later she’d teach harp and organ when the arthritis stopped the violin. Sometimes I’ve got a tremor and I don’t know why, and I’m too afraid to go see the nerve doctor. The smoking, the coffee. It could be a lack of water.

WALTZ: It’s too much coffee.

JONES: Maybe.