In Conversation

Bryan Fogel and Judd Apatow on Why The Dissident Is Vital to This Moment

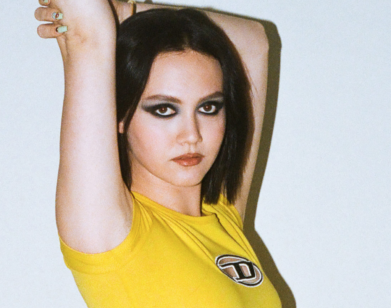

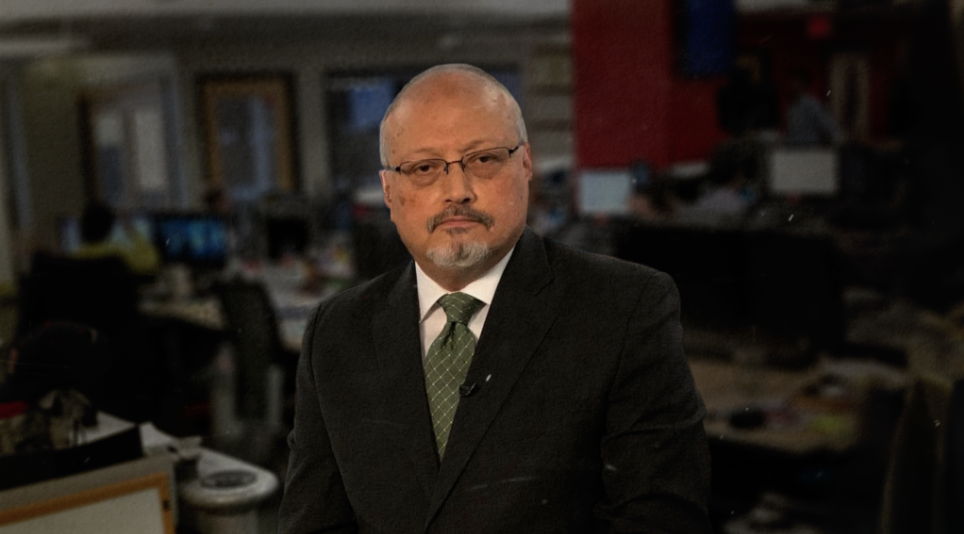

The 2018 murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi sent shockwaves around the world. By now, the broad strokes of the story are well known. Khashoggi, who was a critic of the Saudi regime and of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in particular, walked into the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on October 2nd and never walked out. Khashoggi, it turned out, was brutally murdered by a group of Saudi agents who had been waiting for him inside the consulate, and although he denies it to this day, MBS is widely believed to have ordered the assissination. Khashoggi’s murder and its ripple effects are the subject The Dissident, a chilling new documentary from the Oscar-winning filmmaker Bryan Fogel, who dives deep into the facts surrounding the case. Fogel, whose film Icarus, about the Russian doping scandal, won him an Oscar for best documentary, also uses the Khashoggi murder to tell a bigger-picture story of the silencing of free speech by oppressive regimes around the globe. The Dissident, which was a hit when it premiered at Sundance last year, was passed on by major streaming services like Netflix and Amazon (Jeff Bezos employed Jamal Khashoggi at The Washington Post), for, as Fogel suspects, fears of alienating overseas subscribers. That was among the topics discussed when Fogel recently connected with his friend, the filmmaker and producer Judd Apatow.

———

JUDD APATOW: Hey, Bryan. I watched the movie again last night, and it’s such a strong piece of work. The first thing it makes you wonder is when Joe Biden is the president, do you have any expectations for when he might release all the information that the United States has?

FOGEL: Well, two months ago, on the second anniversary of Khashoggi’s murder, Biden released a statement on Twitter basically saying that if he was elected president, he planned to reexamine the U.S.-Saudi relationship. He added the hashtag #justiceforjamal, and he’s certainly made that promise. There’s been stories in the last week or so, as reported in The New York Times and The Washington Post, that apparently Saudi Arabia has been on a hiring spree of new lobbyists anticipating that the Biden White House is not going to be friendly to the Kingdom. That’s interesting, but at the same time, I’m reading stories of Trump trying to get immunity for MBS from prosecution from the Justice Department before he leaves. It’s fascinating and it’ll be very interesting to see, as Biden takes office, what he will or will not do.

APATOW: It’s such an interesting time in America and in the world because, on one hand, we hear about all of these crazy conspiracy theories and, on the other hand, we’re learning how crony capitalism works. The types of relationships that countries have and people and politicians and business people have, that seems to be an area that you are very interested in: the truth of how countries and businesses interact. Is that something that just evolved when you were interested in the doping scandals or did that predate all of this?

FOGEL: I think I’ve always been curious. I was very much into history in high school and university. I think I started getting a subscription to The New York Times delivered sometime around when I was 20 years old. I’ve always followed stories like this, but the journey of Icarus certainly woke me further to the level of corruption, greed, money, power, and how not only government can work, and when I mean work, I mean work not for the good of the people but for malicious intent, and also how organizations, as long as there’s money and sponsorship and investment, tend to look the other way. And, certainly, that was heightened through the Russian doping scandal and watching the IOC in action, and watching the World Anti-Doping Agency, essentially being complicit as a watchdog agency that couldn’t do anything. And, of course, Russia’s continued response no matter what they were faced with, which was denial, denial, denial. And, look, it’s the exact thing that we’ve seen from the Trump White House over the last four years as well and, certainly, in regards to the Khashoggi murder, it’s been the same, I guess you’d call it, authoritarian playbook that we’re seeing used over and over again.

APATOW: I think also maybe it’s the first time we’ve ever had a politician say publicly what I’m sure many of them say privately, which is, “He’s buying a lot of our weapons and we’re not going to mess up our economy over this.” He basically said he didn’t care and then it came out in the Bob Woodward interview, that he was proud of helping bin Salman get off. I feel like it connects to the entire COVID crisis in how it relates to Donald Trump making a political calculation, that if he downplayed it and didn’t do much about it and looked like the person who was for opening up the country, he would get reelected.

FOGEL: It’s fascinating and, at the same time, appalling in that we’re used to, at least in the United States, this concept of a leader who, at least on the surface, appears to always be trying to do the right thing or at least always appears to be trying to soothe and make the people feel good and say the right things. With Trump, we’ve had a guy who basically is going to go after what’s best for him. I do believe that under Obama, the handling of the Khashoggi murder would have been different, but I’m not certain of the outcome. I’m not certain that the hundreds of billions of dollars of weapon sales would have been blocked. I’m not certain that there would have been massive sanctions. I am certain that, at least on the surface, there would have been a lot more wrist smacking and admonishment, but I just don’t know if the outcome would have been that different.

APATOW: The part that I find most disappointing is how the infusion of foreign money into our media system is silencing free speech and journalism. With all the different ways in which we challenge our country and other countries about certain important issues, human rights being one of them, this film wasn’t picked up by a major streamer. It wasn’t picked up by Amazon, and Jeff Bezos employed Jamal Khashoggi at The Washington Post. Did you see that coming while you were making the film or were you completely blindsided that all of the streamers felt that it was against their financial interest to have a documentary that revealed what Saudi Arabia had done?

FOGEL: I would answer that in two parts. The first part of it is, it reminds me of what happened to the U.S. airline industry a few years ago, or what happened to the majority of big industries, where they became consolidated. Just a few years ago, before the Netflix global streaming environment, there were so many other ways to have distribution. And I think what we’re going to see, even post-COVID, is this idea that all these films that were acquired by the streaming companies during the pandemic and had their first run on streaming platforms, I think only consolidates that power. It is incredibly powerful on the one hand, where filmmakers can have their content seen and digested by massive audiences. But on the other hand, it creates a difficult situation for films that might take on political or controversial subject matter, as these companies are now looking at everything from a global perspective. And so content needs to be friendly to Pakistan as much as it needs to be friendly to the United States, as much as it needs to be friendly to Brazil, as much as it needs to be friendly to Russia or China. If Icarus was coming out into the world now rather than three years ago, I would be highly doubtful that Netflix would take it, as the company has changed. They’ve doubled in subscribers and their future is purely based on international growth, and that growth means, “How do we get more subscribers in Saudi Arabia, how do we get more subscribers in the Emirates, in Egypt,” and so on and so forth. And anything that might tip the apple cart in those regions, it appears that not just Netflix but these global streaming companies are going to help to silence, and that’s unfortunate. It’s not a great time to be a truth-teller in cinema, as best I see it.

APATOW: It seems that, in the worst moments, like during a Trump administration, you don’t have a government that cares about these issues, so it becomes a perfect storm of a silencing of journalism and these types of films, and a government that’s not going to stand up against the types of human rights abuses we’re used to our government standing up for. I wonder how all this changes under somebody like Joe Biden, or under the surface, is it all the same and is the representation of caring about these issues mainly theater, even when there’s a Democratic president? There’s the show that we care about these things, but, ultimately, we’re not going to go that far.

FOGEL: Exactly. And I think what we’ve also seen is what has happened under the Trump White House, and not to take away the responsibility of these media companies and global distributors from pushing forward content such as The Dissident, but what has happened under the Trump White House is that they are punished for doing so. I was told, and I can’t confirm this, but a very close friend of mine called me and said, “I’ll never go on the record telling you this, but Netflix had a meeting with their board right around a year ago, where they discussed that they were not going to not only not do content that would be considered truth to power or anything along that, but they were also going to do their best to not have content that would anger Trump supporters or do anything to upset Trump.”

APATOW: Is there any part of you that has a sympathy for the dilemma of these companies? Because if the head of some distributor or streamer said, “I’m going to put my neck out on the line. I think it’s important that people understand what happened with some issue,” chances are that would probably end their career if they lost a gigantic market. Has a system evolved that’s almost impossible to dismantle? It seems like, in America, the only solution to that is the distributor who has the hook of being the place that has the documentaries that tell the truth.

FOGEL: Well, it’s a great question in that regard. Our industry is one that has brought on a lot of Saudi money, so it is faced with these decisions, and they’re not easy ones to make. because money is money and it’s a powerful force. I don’t know what the answer is. Do you have a thought of what that answer should be?

APATOW: I think what people always assume the answer is is an alternative company that makes their values part of why you want to sign up for their service or give them money. I don’t know if, at this point, the set-up of how it works right now allows for someone to get to the size they need to get to while standing up for these important issues. Clearly, we always hope that, when you engage certain countries, that it will lead to them embracing our freedoms, and I think we’ve found that instead it has silenced people in our country to their abuses, and that’s the deal that we seem to have made. We have to be silent if we’re going to accept your money. I found it heartbreaking when watching your film because it’s very graphic in its details about how Jamal Khashoggi was murdered, and it also reminded me of the documentary Assassins, where they created this fake prank show to trick these two women into murdering the leader of North Korea’s brother. These murders are a show. They are meant to terrify people. They’re an act of terrorism to the world which say, “This is what the result will be if you question the system, if you try to change the system, if you try to fight for what is right.”

FOGEL: These authoritarian regimes, with these murders, whether it’s Kim Jong-un’s brother, but you look at the Putin playbook starting in 2006 with Alexander Litvinenko, who’s poisoned by polonium, literally given nuclear radiation, and then, of course, the flow of murders after that that not only are they sending a message to the world that “We’ll come and get you on foreign soil,” but there is no punishment. Angela Merkel, in the fallout of the Navalny poisoning, gets up there and condemns Putin and says this won’t be tolerated, but are they actually doing anything about it? The answer is no. In the case of the Litvinenko poisoning, British intelligence says, “We are 100 percent sure that this was an act only Putin could’ve condoned.” Did they do anything? No. It’s the same with the Khashoggi murder, om that it goes so far beyond the Trump White House, because it’s a worldwide thing among these G20 nations that have essentially went, “Okay, these are terrible crimes, but what are we going to do? Are we going to send armed forces into Russia? Are we going to start a war with North Korea?” So what we keep seeing is, you can basically murder dissidents or your enemies on foreign soil and, at the end of the day, while you might get a slap on the wrist, nobody’s going to do anything about it. Even further evidence of this is the United Nations where, as you see in The Dissident, Agnes Callamard, the Special Rapporteur, presents a damning report to the Human Rights Council, which is essentially just a watchdog agency, they can’t do anything other than to observe and report, but she says the UN General Assembly and the Security Council needs to take up this case and further investigate the Khashoggi murder, and the Security Council decide not to, essentially giving a free pass to Saudi Arabia because it’s not even in the interest of the UN to do something about this. What we are seeing right now is that these sort of crimes will continue because these authoritarian regimes are learning over and over again that they can get away with it and, certainly, it’s sending a message back to their people to think twice before they voice an opinion or dissent or do anything that might anger their government.

APATOW: Wouldn’t other countries say that our country’s interventions around the world are a form of the same thing?

FOGEL: I think that has been the argument for so many years and, certainly, that has been the argument in the case in the Middle East, but I think what we’re seeing now is that the United States, especially in the last four years, is becoming less and less of the global superpower that it once was, and that the battlegrounds of warfare are becoming increasingly less dependent on rocket launchers and stealth bombers and much more so on essentially cybersecurity and hacking and security viruses and things that can be far more disrupting to a society than a bomb or a missile.

APATOW: I do want to make sure that I say I think it is a brilliant documentary. I really appreciate that you made it, and I understand what it takes to do work like this in this day and age. If we could find anything positive in the world right now, and we’re talking the day after the election in Georgia, and after Joe Biden, is that the majority of people in the United States would like to see our country stand for something and not just be part of some global economic system where human rights are not important at all. I guess we’ll find out how the Biden administration feels about all these issues, and one hopes that, once again, they’ll become a priority. I certainly was haunted by the gentleman in your film, Omar Abdulaziz, who has taken so many chances at such great cost to himself and his family to try to speak up for people in his country who have no voice. How is he doing? How is his family doing?

FOGEL: The film was nearly completed, at least in its principal photography, about a year ago. We went back and did six months of additional graphics work and editing and sound and finishing the score and polish post-Sundance, but the film was largely finished a year ago. I bring that up because Omar Abdulaziz, the Saudi dissident who lives in self-exile in Montreal, while we were filming with him, learns that not only are his two brothers imprisoned in Jeddah, but that they have been tortured, essentially for doing nothing more than knowing Omar and being his brothers. These guys are not political activists. They weren’t doing things to upset MBS, but were simply pawns. And the Kingdom also arrested, at that time, 23 of his friends, because they had hacked Omar’s phone, as you see in the film, which is frightening to say the least. These people are still in Saudi jails, not charged with crimes, and sitting there, essentially in retribution for Omar’s activism, which continues from Canada. So Omar is doing okay, but he is faced with a decision every day, and that decision is to be silenced, which is what Jamal Khashoggi refused to do, and if he silences himself and shuts down his Twitter and shuts down his YouTube, there’s probably a very high probability that his brothers will be released from prison. Or, he keeps speaking truth to power while his brothers sit in this jail, tortured, without charges, for his activism. I don’t know how Omar makes those choices because I think it’s unfathomable that we live in a world where this can not only happen but is happening right now.

APATOW: I implore everybody out there to see The Dissident. It couldn’t be a more important film for this moment. People should educate themselves about what’s happening in Saudi Arabia and around the world and what these issues are, because we are all part of that system, we are all spending our money supporting companies, and we do have the ability to force change on them and, when you take the time to truly understand what’s happening, I don’t see how anybody would not want to lend their voice and their support to a world with less human rights abuses and horrors. And we do have to put as much pressure as we can on the Biden administration to take very forceful action on all of these issues.

FOGEL: You’re 100 percent right, because when you look at all these social movements that actually succeed, it’s been said that Jamal Khashoggi was the last martyr of the Arab Spring and the Arab Spring began in 2013 by people taking to Twitter in Egypt and in Libya and in countless countries, who were basically saying, “We deserve better. We can have better government.” And the same can be said with the Black Lives Matter movement. We have seen that change can come time and time again, when the people are willing to hold their leaders or government accountable for their actions. That is the optimism that I have, not only in the case of Jamal Khashoggi and his murder, but in the optimism of Biden coming into office, and also in the optimism of seeing how people can actually, starting from an individual level, create meaningful change. And in regards to holding these companies accountable, I think it’s about having enough people standing up and going, “Hey, we might reassess our relationship with you guys if you don’t change your policies to better protect human rights.” I do have that optimism.