SUPERSTAR

Brontez Purnell on Paul Morrissey, the OG Edgelord

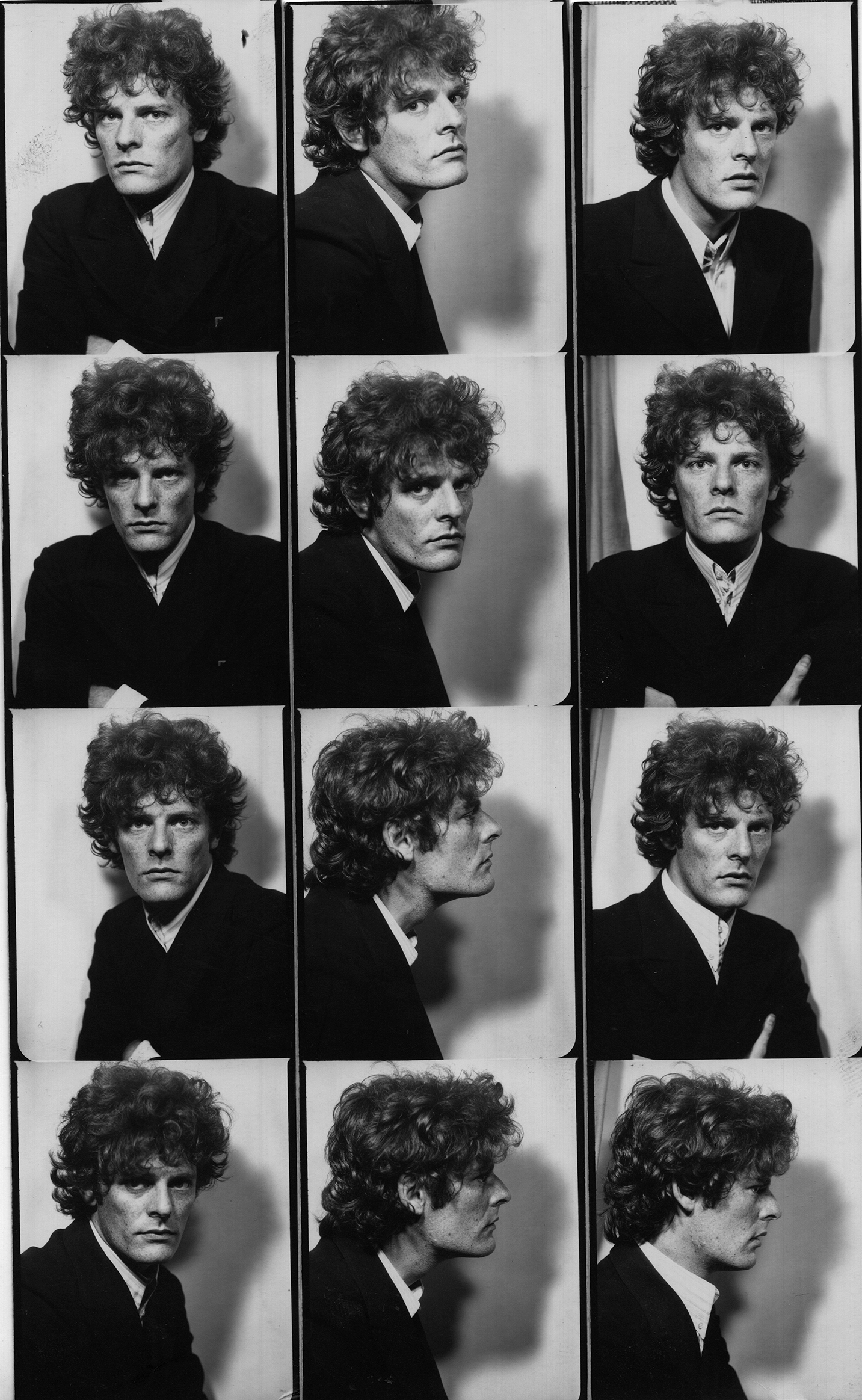

Self-portraits, 47th Street Factory “Four for a Quarter” Photo Booth, 1967. Archival Photos Courtesy of The Paul Morrissey Archive.

It need not be reiterated that Andy Warhol, our spiritual father and the beloved founder of this very magazine, predicted the destiny of pop culture a bajillion times, like in 1968, when he said, “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” Long story short, with social media, fame has become so overly democratized that it’s practically meaningless, which is actually so cunt if you think about it—but that’s an essay for another day.

What I mean to say is, in all his artistic pursuits, Warhol’s obsession with cinema laid the groundwork for a lot of the current conceptual models for television and entertainment today. I remember doing a reading at the Warhol Museum with Justin Vivian Bond in my twenties and, after seeing a survey of Warhol films, Justin casually whispering in my ear, “You know, they made A LOT of ugly shit.” But I also remember seeing Beauty No. 2 for the first time and being amazed that it was essentially Edie Sedgwick playing herself, not unlike the unscripted reality dramas that were beginning to RULE the television landscape. What this meant was that Andy and his both divinely and poorly chosen group of Factory-dwelling disciples weren’t just a bunch of ’60s hipsters who did a shit ton of meth, they were also prophets. Enter the work of Warhol archbishop, the director Paul Morrissey.

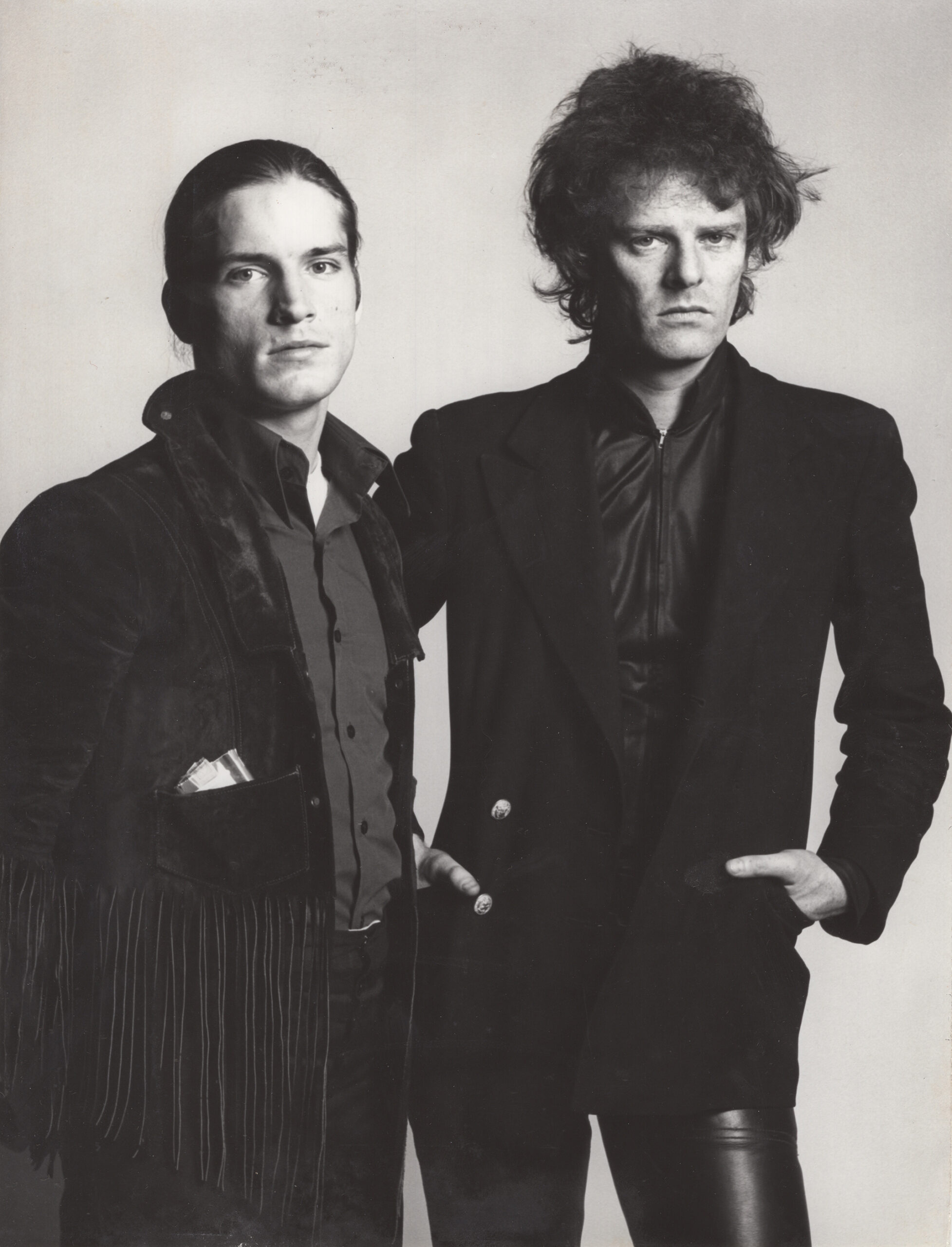

Paul Morrissey with the cast of Trash, Holly Woodlawn, Joe Dallesandro and Jane Forth, 1970. Photo by Henri Dauman.

Morrissey is a hard person to place in the Warhol pantheon, and his legacy is marred by a number of refusals. According to the film critic Sam Weisberg, he is an “unapologetic conservative and devout Catholic [who] hated hippies, the sexually liberated, drug users, and rock music enthusiasts.” And while this scorn undoubtedly contributed to Morrissey’s resentment of the Factory in general (he feels Warhol took too much credit for his work), the director’s own legacy is not without contradictions. A clean religious boy who spent his time around degenerates? I’ve seen the biggest freaks of my generation turn alt-right in front of my eyes (usually out of spite or more likely, boredom—maybe Morrissey is the earliest example of how too much time in outlying incubators can breed contempt?). But in a world where leftist politics can start to feel like church camp, we shouldn’t throw the baby away with the bathwater. In this case, one who devotes his life to cleanliness also devotes his life to dirt. Morrissey became a revolutionary filmmaker, directing a dozen Warhol films chronicling the life of mid-century deviants, and what a chronicle it was! He was one the first directors to actually cast trans women in movies, not to mention the outrageous displays of sex and full-frontal nudity he put onscreen.

In my youth, I used to say that within the holy trilogy of the Morrissey-directed flicks Flesh, Trash, and Heat was a tone best described as a John Waters film turned into a serious drama. But what I now see in these monologue-driven movies filled with long pans punctuated by too many focus pulls (a genre later to be codified as mumblecore) was a kind of genius. Cinema should be about style, be it good or bad. But we live in a deeply unglamorous era where the general public has been duped into watching 10-hour-long streams of shows, all sound-scored and color-corrected into one monotone buffet to be devoured on computer screens. Within this context, there’s something quite magical about looking back on the deeply earnest, meandering monologues of Morrissey’s characters—characters who were defiantly appearing on the screen for the first time ever, defying the old Hollywood codes that declared that any deviant had to die in order to preserve the moral purity of the plot.

Improvised naturalistic acting, low budgets, and an emphasis on relationships and dialogue over plot, are all stylistic tropes that over the years wax and wane in popularity, but the prime movers of this pantheon remain classics. In fact, to this day, Morrissey’s collaborations with Warhol are some of the most successful mismatches in all of American film history. Plus, the fact that he landed the gig because he was not a novice but actually, gasp, skilled, negates the fact that one of the last remaining popes of queer-focused indie cinema was not a homosexual.

———

Archival photos courtesy of the Paul Morrissey Archive.