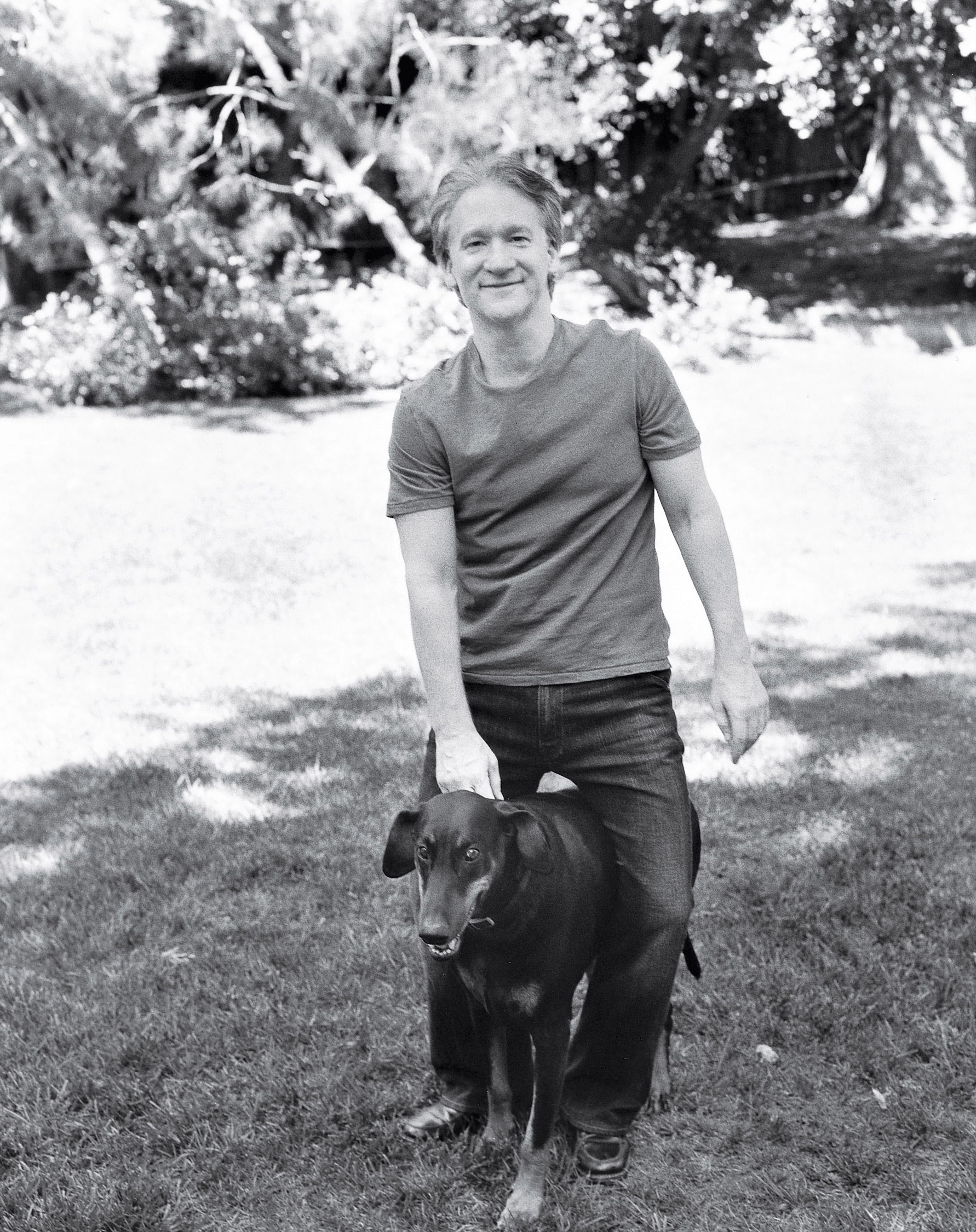

Bill Maher

Avoiding controversial, difficult, or polarizing subject matter has never been Bill Maher’s strong suit. So it’s appropriate that for his latest project the comedian would take on what is perhaps the most divisive subject in human history: religion. Directed by veteran comedy writer Larry Charles — instigator, helmer, and shaper of Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat (2006) — Maher’s new film, Religulous, is a globe-trotting exploration of what we believe, why we believe it, and the mess it has all created.

DAVID STEINBERG: First of all, what a perfect match: you and Larry Charles.

BILL MAHER: You know, I’ve wanted to make this movie forever, and, as you well know, in the movie business, so often it is a case where you don’t really do something until you find the right guy to do it with. And I finally found the right guy. Over 25 years, Larry Charles and I traveled in the same circles, played the same clubs, knew the same people, and somehow we had never met. It’s like a French farce, you know, where the door opens just as the other door opens and one guy goes out and the other guy comes in.

DS: You were everywhere together and just never saw each other.

BM: What can I say? Fate saved us for the right moment.

DS: Now, I don’t know if you know how Larry Charles and I know each other. He was the only writer I could work with on The Tonight Show who could actually write things for me that I would say as my own-where Johnny Carson would say, “Oh, that was vintage Steinberg.” Once that happened, I thought, Oh, I found a writer to work with.

BM: That’s another thing about Larry Charles that I discovered while we were in so many different places together, with lots of time on our hands to just chat: He, over the course of his career, has written for everybody.

DS: Larry wrote for everybody. I was very sort of antiestablishment, or whatever the term was at the time when he was writing for me, but it was never enough for him. He wanted me arrested and in jail. That’s the only way he would have been happy.

BM: You know what? I had the same experience with him. He is a brave man, braver than I, and he wanted us to do things that were really quite . . . We did get thrown out of a lot of places. I’m not saying that he didn’t get his way. But we weren’t killed making Religulous, and I think he’s disappointed.

Laughter is sort of a natural truth detector. BILL MAHER

DS: Tell us about Religulous.

BM: I’ll just tell you what I told the studio when I pitched the movie, which is that it’s a topic that I have been talking about on television for the last 15 years, and I always thought I kind of owned it. Although I certainly owe a debt to George Carlin, who talked about religion in scathing terms early on. But as far as somebody on television on a regular basis speaking out against religion, I kind of own that.

DS: Yeah, no question.

BM: So when I pitched this, I just said: “For a comedian, the topic of religion is the side of a barn. If you can’t hit that . . .” Because as a comedian, I think we all look for those areas where the truth diverts from what people are saying. That’s why politics is such a rich area for us, because politicians make promises, and they don’t keep them, and when we point out the difference, we get the laugh. And politicians will promise some pretty ridiculous things. They will promise a chicken in every pot. They’ll promise that they’ll keep Social Security solvent. They’ll promise drugs for old people. They’ll promise lots of stuff. But it doesn’t come near the kind of promises that religion makes. The Mormons promise that if you’re good while you’re on Earth, you get to rule over your own planet in the afterlife. Now, there’s an entitlement that goes a little bit beyond prescription drugs for old people.

DS: Religion is still the most volatile topic. More than politics — more than anything else, really.

BM: Oh, yeah. And let’s be honest. This country has a long tradition of not even talking about religion. I interviewed my mother for this movie, and she made an interesting point. I don’t think we used it in the film, but she said, “When you kids were growing up, you knew all our friends, and we never even knew what religion people were. It was just something people did not discuss-even close friends.” It’s like, yeah, we knew the Ladds were Catholic, but we didn’t go there. We knew they weren’t Jewish. But what denomination, how often did they go to church — it just wasn’t a topic of conversation. Just like you didn’t talk about it when John F. Kennedy was fucking around. That was just not something people ever discussed. That was the time.

DS: Our religion was private. Is that what it was?

BM: That’s just the way the country was. It was just something that people didn’t discuss. Of course, I think one reason why this movie has resonance now, or maybe Americans are finally coming to a point where they’re accepting of religious criticism, is because George Bush is the first president who really put religion so front-and-center. He’s the most Christ-y president we’ve ever had — and he is, not uncoincidentally, the biggest disaster we’ve ever had. I think even people who are religious don’t like it shoved down their throat. I think people kind of get it on a certain level, that this is an antiscience administration, and we’re living in a time where we can’t afford to be antiscience — for environmental reasons, for educational reasons.

DS: So did you get the humor in the film? Because when people are earnest, they’re funny.

BM: I said from the beginning: We don’t really have to make fun of religion — it makes fun of itself. When you see all of the evidence marshaled together like it is in this film, and you see how ridiculous this stuff is . . . If you came into the theater believing in the talking snake, it’s kind of hard to leave the theater still believing in the talking snake.

DS: Right. You can’t do better than that. So where did you go?

BM: We went to Jerusalem first, and then we went to London and Amsterdam and Vatican City, then we started on the American leg and went through the Southeast, and then Salt Lake City, Boston, New York.

DS: Had you ever been to Israel?

BM: No, that was my first time.

DS: Forgetting about the film, what effect did Jerusalem have on you?

BM: I think what I came away with was the idea that the Jews, although less warlike than the Christians and the Muslims, are no less crazy. I mean, I used to call Jerusalem “the funny-hat capital of the world.” Everybody in that town is wearing a funny hat, a funny outfit, doing funny things. But I especially wanted to go to Jerusalem. I wanted to make the point — and I think we do in the movie — that although the media constantly portrays Jerusalem as the spiritual capital of the world that’s somehow coincidentally home to the three great religions, that’s all complete bullshit. The reason why the three religions are there is because the city was conquered by each. The reason why, for example, the sacred Al-Aqsa Mosque is right on top of the Temple Mount is because religions conquered each other, and it was a lot easier just to hang a new sign on top that says UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT than it was to build a new temple. That’s how temples became churches, and churches became mosques. In the movie I say, it sort of reminded me of how, when I was a comedian starting out in the ’80s, very often you’d be in a comedy club that you could tell was a disco in the ’70s, because the disco ball was still hanging there. In the ’90s they became strip clubs. Now they’re Starbuckses.

DS: Yes. Often, if you go into areas where Jews used to be in the ghetto, now African-Americans are in the ghetto and the synagogues are now churches.

We don’t really have to make fun of religion-it makes fun of itself. BILL MAHER

BM: That’s a very apt analogy, that the slums were taken over by succeeding minorities. The Irish came to America and they lived in a tenement, and then they moved up in the world. Then the Italians came to America and they lived in that tenement, and then the blacks lived in that tenement, and then the Puerto Ricans.

DS: The rule of satire in my mind is that you can’t presume that you and your audience hate the same thing. But as a comedian, you identify yourself by what annoys you, not by what you love.

BM: [laughs] Very true.

DS: So what surprises you about doing your HBO show Real Time? As I see the names roll by of the people who are going to be on the panel each night, it’s hard to know who’s going to be good and who’s not going to be good. But on your show, it’s so interesting, because your guests have to be smart. They have to impart some knowledge. They have to at least know what they’re talking about.

BM: Well, I’ve noticed that you’ve resisted coming on for the longest time.

DS: You remember why. I’ll remind you again: It’s because I’m a Canadian, and when three people are asked a question, I’m much too polite to jump in. I would just sit there. That’s my excuse.

BM: I know. But you would be great on this show. Which is why we keep asking. Part of what makes it work is chemistry. As you know, with a panel, they sort of take on a life of their own. We like to try new people, and we try to vet them as much as we can, but you just never know until you get out there. Then there are some people who are great in the green room-

DS: But not good on the show.

BM: In the green room they have a myriad of fascinating things to say, which for some reason they feel are inappropriate to enunciate on camera.

DS: When I was doing The Tonight Show in the old days, I used to go hang out with Carson in the afternoon before we did the show.

BM: You’re kidding. Really?

DS: Yeah. I’d come in at 11:30 A.M., and then we’d go out to dinner afterward. So in the afternoon, we would be laughing. Just like you and I are talking now, we would be exploring our ideas. Then I would go on the air, and it wouldn’t be that funny.

BM: It’s so surprising that he spoke to you before you went on the show. I’ve never heard anybody say that about Johnny Carson. He must have adored you, because he was such a loner, and I know that he always wanted to make the magic happen on camera.

DS: He did. How early I would come to the show was always the joke. We would have lunch and hang out. But he stopped me. He absolutely said, “We have to stop the afternoon meetings because we’re losing the material.” You can’t repeat what you said in the afternoon on air that night. It just makes you feel like a schmuck.

BM: You know, in 15 years, between the two shows — Politically Incorrect and this one — I’ve never once talked to a guest before the show.

DS: Because you’re a comedian, and you know what that does.

BM: Yeah. Also, I don’t like people.

DS: I understand that. . . . Which brings me to another point: Something we both have in common is sort of an animal activism.

BM: Oh, yes. I love animals.

DS: I’ve been a vegan for quite a few years.

BM: Good for you.

DS: But I see you make points about animals and stuff on the show occasionally. Do you get any reaction to that from anybody?

BM: Oh, absolutely.

DS: What happens?

BM: Well, sometimes it’s a hateful reaction because I always take the side of the animals. I remember once we were talking about this story involving the Make-A-Wish Foundation. I guess this poor, sick, dying kid had a wish to kill a bear. Well, really, I’m so sorry the kid is dying, but why should the bear suffer? So I took the side of the bear, and of course, it becomes, “Bill is against the wishes of sick, dying kids.” I was pretty unsympathetic, but I’m pretty hard-core about this issue. For example, I don’t believe in horse racing. People always say, “My horse loves it. My horse loves me.” And I’m like: “You know what? Unless your horse is Mr. Ed and he told you, you don’t know that the horse loves you. What we do know is that a horse in the wild doesn’t have a bit in its mouth and a saddle and a person on its back. But what you did is you broke the spirit of the horse.” I don’t know. If someone had a bit in my mouth and was jerking on it, I don’t think that would make me happy. So, you know, if you get on top of a horse and it throws you off, that’s sort of what it’s supposed to do.

DS: What I really enjoy about watching you is that people can’t get you on anything because

you’re not hiding anything.

BM: No. When the tabloids photograph me when I’m out, I always say: “You know what, folks? I’m not married and I’m not gay. You caught me with a hot chick. You got me. Take me to hot-chick jail. Did it again. Guilty.”

DS: As a comedian, that’s got to be liberating.

BM: When I do stand-up around the country, I often see people walk out. This is a show that they’ve purposely gone to, where my name is on the ticket, and it cost them $75 or something. So, you think, Wow, that means that they either didn’t know very much about me when they bought their tickets or they’re that offended by what I’ve said. I’ve been doing this a long time. Anybody who comes to one of my shows must sort of have an idea of where I’m coming from.

DS: It’s always amazing, isn’t it? They have to know who you are, and yet they’re going to get offended at what you say when they come into your audience. I’ve always found that puzzling myself.

BM: Yes. Sometimes I see people in the very front row with their arms folded and a grim look on their face, just hating on me. I think maybe they think that they could get that seat and sit there and stare at me like that, and it would throw me off my game. It must really fuck them up when, of course, I’m anything but thrown off my game. I relish that. I use it as inspiration. I just want to make everybody else in the audience laugh so much harder.

DS: And you talk right to them at that point. You look them in the eye and make it even more uncomfortable.

BM: Right. Of course, there’s material that I have that’s not really that political, where I can get them laughing. So then, if I get them laughing at a certain point, then I’ll stop and then I’ll stare at them. I’ll give them the evil eye. “See, motherfucker? You’re laughing now, so I must be right about this. Maybe I’m right about the other thing.” Because that is one of the great things about laughter: It’s an involuntary response. Laughter is sort of a natural truth detector. If you laugh at something, it’s probably because there was some truth in it.