Free Willy: Being Bradford Dillman

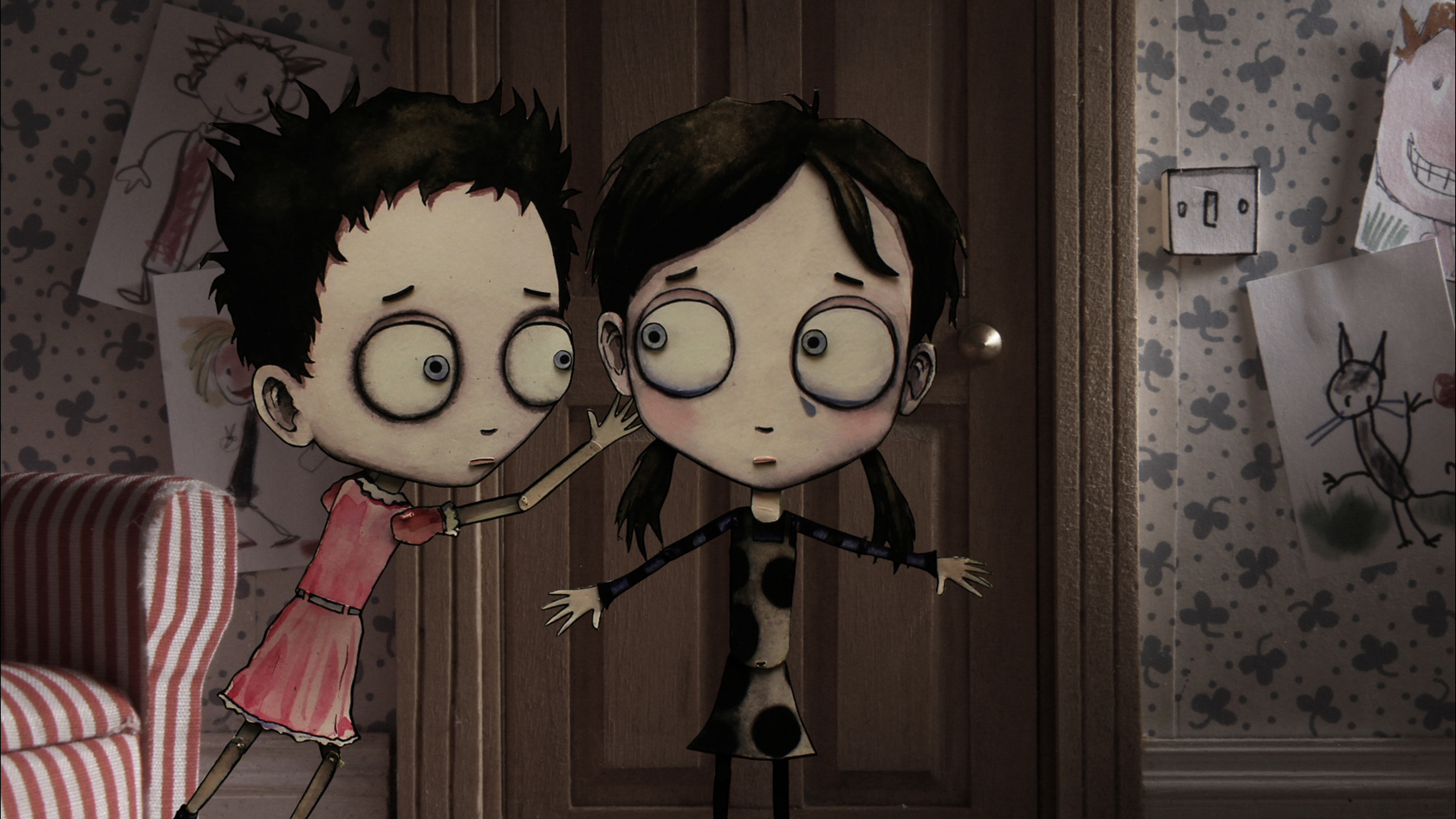

ABOVE: A STILL FROM BEING BRADFORD DILLMAN, COURTESY OF THE FILMMAKERS

A pill-popping, alcoholic mother and her castrated daughter aren’t regular material for children’s animations. Yet co-directors, designers, and producers Emma Burch and Pete Williamson were able to turn such macabre material into a charmingly gloomy independent short, Being Bradford Dillman.

The two friends met while doing commercial work at a London agency. Recognizing mutual feelings of creative suffocation, they instigated a personal project, which took many evenings (and bottles of wine) to complete. Produced in pubs and the basement of a Soho hairdressing shop, Being Bradford Dillman‘s DIY spirit is rivaled only in its equal helpings of heart and humor.

We spoke to the London-based duo before their short makes its stateside debut this weekend at the New York No Limits indie film festival.

MICHELLE LHOOQ: Where did this story come from?

EMMA BURCH: My mom. I’m still not sure why, but she told me exactly what the mother character tells Molly in the film—that I was born a boy but the doctors chopped off my willy at birth and she kindly kept it for me in a shoebox on top of my wardrobe. Oh, and that my real name was Bradford Dillman. Whenever I tell this story, I always get extreme reactions. People would either find it hilarious or absolutely abhorrent that a mother could tell her child such a terrible lie! I knew there was no malice in it, though.

LHOOQ: Did you have a weird childhood? Any imaginary friends?

BURCH: I think it’s clear that my childhood was a little, um, alternative.

PETE WILLIAMSON: Mine was really happy until I collided with the adult world and have been reeling ever since. I didn’t have an imaginary friend. Real children were more fun and had better stuff.

LHOOQ: How do you two know each other?

WILLIAMSON: We worked together in London at an animation company specializing in puppet commercials. It all had to take place in the evenings. We usually got a bottle of wine to get us out of commercial work mode.

BURCH: Commercials can be restrictive creatively. Pete felt the same, so we teamed up after a few sessions at the pub. It took 78 months from start to finish. We should have kept a bottle count!

WILLIAMSON: I tried, but gave up after the first year.

LHOOQ: How would you describe the relationship between Molly and her mother? Besides “unconventional.”

WILLIAMSON: Her mother keeps forgetting that she’s supposed to be protecting Molly, rather than the other way around. We didn’t want the mum to be a bad person, just someone whose personal pain kept getting the better of her and affecting her child.

BURCH: Yeah, it’s the whole role reversal set up. How do you feel about that situation since you’ve become a dad, Pete?

WILLIAMSON: I think my daughter is more likely to tell me weird stories. She’s already got a mischievous glint in her eye.

LHOOQ: Last Halloween, I saw a little boy dressed in a Disney princess costume going trick-or-treating with his dad. I was reminded of that when Bradford cavort around in Molly’s dress. Were you trying to say something about the malleability of children’s sexuality?

WILLIAMSON: It wasn’t a direct commentary, just Molly and Bradford in their own little world, blithely doing something that society would find odd and unsettling. And it is a nice dress.

BURCH: It was simply about Molly imagining Bradford in her favorite outfit, as they’re ultimately the same person. Bradford is the boy Molly would have been, had the doctors not chopped off her willy. I hadn’t considered the children’s-sexuality angle, but a couple of gay friends have told me that side of the film really struck a chord.

LHOOQ: Why did Molly feel compelled to invent an alter ego?

BURCH: Bradford is supposed to be the boy she would have been and an alternative life she could have led. Molly’s experience of boys is that they’re rude, obnoxious bullies, but she actually sees them as confident and fearless—traits she wishes she possessed.

LHOOQ: Pete, where did your illustration style come from?

WILLIAMSON: I took cuteness and pushed it in an extreme way that became unsettling—children with large unwieldy heads and enormous eyes that seem to have seen too much of the world. In a way I was trying to subvert the appeal of the design work I was doing for commercials, and create something darker and stranger.

LHOOQ: Were you influenced by other films or directors?

WILLIAMSON: In terms of the idea of a neurotic parent and a child’s attempt to cope, I was really influenced by Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale. Also Withnail and I for its bleak humor and emotional claustrophobia. The heavily-shadowed sets were inspired by Bela Tarr’s The Werckmeister Harmonies.

BURCH: I saw Alex van Warmerdam’s The Northerners as a teenager at Glastonbury, and it really stayed with me to influence my ideas about filmmaking. It has a lot of locked-off, beautifully composed shots, and an eccentric cast of characters with complex relationships.

LHOOQ: What interests you about adult-themed children’s movies?

WILLIAMSON: The strange wonder of really good animation adds a magical, haunting dimension to storytelling and gives a weird edge to adult themes. The necessary obsessiveness usually seeps into other areas of a film, too, and gives it more weight and character.

BURCH: I don’t know. Films that tap into that universal feeling of childhood vulnerability particularly interest me, as that feeling has never left me.

LHOOQ: What do you think the medium of animation affords that others don’t?

BURCH: I think the film would have a much darker tone if it had been live action. Animation helps soften the edges of awkward, hard-to-swallow subject matter, while still being equally thought-provoking and moving.

LHOOQ: What kinds of techniques and technology did you use?

BURCH: We cut out puppets and shot on glass against a green screen in the basement of a hairdresser’s in Soho, London. Our illustrator sometimes had to animate while the hairdressers wound down after work by wrestling with each other at the other end of the basement. That probably added an indefinable something. We used a Canon 550D, a couple of Kino Flo lights and Stop Motion Pro. The background plates were physical model sets made using doll’s house furniture and fittings I had sourced on eBay.

LHOOQ: Given that both of you work in advertising, what’s the difference between that and the indie film world?

BURCH: There’s a lot more passion in filmmaking. People work so hard and risk so much, even mortgaging their houses to make sure their stories get to the big screen. That amount of drive and passion is really inspiring.

WILLIAMSON: It’s great to be involved with something that doesn’t have the sole purpose of selling a product. And we get to wear a lot of black and drink a lot of bad coffee. I was so keen to work on this film because I had gotten to a point where I felt that my commercial work had made me somehow irrelevant to myself. But all the commercials paid for the wine, and the frustration we felt with advertising meant we had an overwhelming desire not to compromise in telling the story.

LHOOQ: I would love to see this short turned into a feature-length.

BURCH: We’re working on a movie where Molly goes to Glastonbury Music Festival with a new friend. Festivals can be the most magical place for children, but obviously have a scary and dangerous side. We just have to find time to edit our many ideas.

LHOOQ: In crossing from the UK to the US, will your film have to overcome cultural barriers?

WILLIAMSON: Obviously it’s not a Disney film, but I think its dark humor and cheerful cynicism should translate fairly well. Being Bradford Dillman has a constant background hum of boozy gloom, and Pixar showed that you can address adult emotions in children’s animation profoundly.

BURCH: We did realize that the “willy in a box” line would have a meaning that we don’t mean it to have. But we never wanted to change the script to accommodate different audiences.

LHOOQ: What do you think the future of animated films will look like?

WILLIAMSON: I really hope that the cheapness of technology will lead to more personal, experimental, emotionally raw and honest films that don’t have to be filtered through accountants and middle management and sales teams to get to a public. I hope it will be like alternative music was in the ’80s. It will be fascinating to see low-budget work from India and China.

LHOOQ: Excuse my American ignorance, but what exactly is a “wally”? Molly gets called that a lot.

WILLIAMSON: It was a mild term of abuse that was popular in British sitcoms in the ’80s and ’90s. Particularly by teachers towards children.

BURCH: I’d dread to think what the kids say nowadays.

BEING BRADFORD DILLMAN WILL SCREEN THIS WEEKEND AT THE NEW YORK NO LIMITS FESTIVAL. FOR MORE ON THE FESTIVAL, VISIT ITS WEBSITE.