Ashton Sanders Tells Tessa Thompson Why Hollywood Can Be a Little Sus

Coat by Loewe. Pants by Gucci. Anklet (worn as necklace) by Sacai. Socks by Nike. Shoes by Pierre Hardy.

The beginning of the rest of Ashton Sanders’s life came in the final moments of the 89th Academy Awards. As he stood onstage with the rest of the cast and crew of Moonlight, it dawned on him that his movie, which marked his first major role, had won the Best Picture award following the envelope blooper seen around the world. The 24-year-old actor had already been tapped for stardom for his role as the closeted teenager Chiron in Barry Jenkins’s lyrical paean to masculinity, but after the movie’s year-long march to Oscar glory ended, it fell on Sanders to make the most of his moment. He did just that, playing a soft-spoken misfit who falls into the world of a wealthy white family in Native Son, a modern adaptation of Richard Wright’s Depression-era allegory, and then as the hip-hop guru RZA in the Hulu series Wu-Tang: An American Saga. Both roles hinted at a young actor ready to shoulder the responsibility of telling penetrating stories about the Black experience in America.

This year, Sanders continues that mission, appearing as a newly incarcerated man in Netflix’s prison drama All Day and a Night, and as the Black Panther Party member Larry Roberson in a still-untitled film opposite Lakeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya. Sanders’s unflinching willingness to confront difficult subject matter through his work has earned the California native many admirers, among them the actor Tessa Thompson, who recently connected with him while the two were in Paris, for a light conversation about heavy things.

———

TESSA THOMPSON: You and I met briefly once. I don’t remember where.

ASHTON SANDERS:I think it might have been at the Vanity Fair party after the Oscars. I was wearing a kilt, right?

THOMPSON: Yes, you were. I don’t think I’ve seen you since except for on social media, which skews our understanding of how well we know people. A lot of people have ideas about you, but maybe they come more from what you wear, because you occupy this fashion space. Is that weird?

SANDERS: Honestly, I’m just being me. I’m not trying to do anything. Style, or the way I dress, has always been an extension of who I am, whether it’s wearing the same jeans everyday or wearing a kilt. I’ve always felt comfortable with how I dress.

THOMPSON: I do think there’s something interesting about being a person of color, being inside of a Black body, and the very narrow ways that Hollywood is able to see us. I think there’s a utility in dressing in all these different ways. It’s like a visual reminder that we’re not a monolith.

SANDERS: Totally. Hollywood puts us in boxes, and I wouldn’t say I’m the average Hollywood archetype. I think that also reflects in my work. I’m never doing the same type of character more than once, because I’m aware of the boxes that Hollywood puts Black men and Black people in.

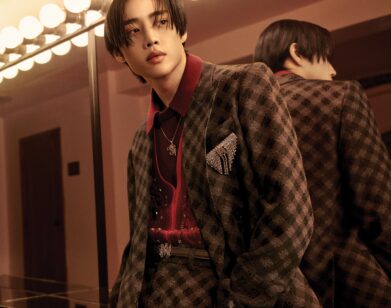

Shirt, Pants and Belt by Paco Rabanne. Necklace Stylist’s Own.

THOMPSON: I’ll never forget when I saw you in Moonlight. I was sent a really early link to it. I put it on in a London hotel, and I was shook. I felt like I couldn’t move. I stayed in that hotel room for the rest of the night. I was also on the jury last year at Sundance, where I got to see you in Native Son, so I’ve been following your work. You bring something new to every part you play, but I’ve also noticed that you seem to want to talk about race and class. Is that intentional or are these just stories you love?

SANDERS: It’s intentional. We have to be strategic about the type of work we do. I’m just coming off of a movie I did with Lakeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya. It’s about Fred Hampton, who was a Black Panther Party leader out of the Chicago chapter, and who was shot and killed by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI in the middle of the night.

THOMPSON: You play Larry Roberson in it. What was that process like in terms of research and execution? I know from doing Selma that it felt like we were really excavating all this stuff.

SANDERS: It was an ensemble project, so we would all come together and speak about the Black Panther Party during that time. We were blessed to have Fred Hampton’s son and wife speak to us and put us in the world of what was really going on. In terms of my personal research, I didn’t really have a lot to go off. There wasn’t anything online that directly links to my character outside of his death certificate. I was working with a voice and speech coach to get the cadence of the time right.

THOMPSON: You’re racking up these collaborations with young directors of color. I know you just worked on Joe Robert Cole’s movie, All Day and a Night.

SANDERS: I did. I worked with your boy Jeffrey Wright.

THOMPSON: How was that?

SANDERS: Fucking crazy.

THOMPSON: Do you have moments of impostor syndrome or are you able to settle into a space of believing, “Yes, this is where I ought to be.”

SANDERS: It always seems like shit is moving so fast. Like, after the initial excitement of finding out that I was going to be acting opposite Denzel Washington [in The Equalizer 2], I had to remind myself that it’s work. I can’t be fanboying. I have to deliver. Working with Denzel was a learning experience. That was my first blockbuster coming off of these arthouse projects, so it felt new at first, but you get into a groove. Working with Jeffrey Wright was the same. I was just really excited to dive into the script with him, because the story is so important. He plays a father figure in my life who goes to prison when I’m a kid. My character grows up trying not to go down that path. But that’s the path in front of him, and he ends up falling into it. We relink as father and son in the same prison and cultivate a relationship there.

THOMPSON: I actually got to watch it very early this morning. It’s beautiful, and you and Jeffrey played really well together. What was that like in terms of research into the criminal justice system? How angry did you find yourself in preparation for that?

SANDERS: It’s no secret that the criminal justice system is so fucked up. We were shooting the film around the same time all these other projects like When They See Us [a miniseries about the Central Park Five] went into production. At the time, all of the fucked-up, corrupt political shit was all around me, all around us. It was almost like we were swimming through it.

Coat by Comme de Garcons Plus. Shirts, Shorts, and Bow Tie by Sacai. Necklace Stylist’s Own. Shoes and Socks Ashton’s Own.

THOMPSON: At various moments, I’ve been like, “I want to do a movie that’s fun.” Do you have that desire, to take a break from something that feels heavy?

SANDERS: I’m not opposed to stepping out of these genres and doing something a little lighter. But again, it sometimes feels like a needle in a haystack when it comes to thinking about what you want to do next and what’s available for Black actors.

THOMPSON: I got sent a very sweet document with talking points about you, and one of the quotes that I really liked of yours about the industry was that “it’s sus as fuck.” I can’t think of a better way to articulate it.

SANDERS: I say it all the time. I don’t want to spend too much time talking about it, but I don’t think it’s any secret. For Black artists, there’s a lot of bias in the industry that just doesn’t feel right. It naturally doesn’t feel equal. I’m still going to have a career, but Hollywood is fucking sus and that’s just what it is.

THOMPSON: What is it about storytelling that you love?

SANDERS: I think art in general is dope. Every role feels like it’s an extension of me, or it’s farther from me. It’s that thin line. But I’m doing it on either side of that line, shedding my skin and hopping into another character and living another life for two to six months.

THOMPSON: What’s the last thing that really moved you?

SANDERS: I just watched Jojo Rabbit on the plane to Paris and that was a great film. Some films the Academy nominates are mediocre. They’re mediocre-good. Jojo Rabbit was surprisingly not one of those films. I was like, “Damn, that film definitely de-served the Oscar nomination.”

Shirts, Shorts and Bow Tie by Sacai. Necklace Stylist’s Own.

THOMPSON: The year that Moonlight won, I was at home getting ready, having someone paint my face, and I have to tell you, it was one of the few times in my life when my jaw genuinely dropped. Was that such a surreal experience?

SANDERS: It was like being on a rollercoaster. We thought we hadn’t won, but then in a second, we did win. That was really trippy. There was a lot going on in my head. That film took six weeks to shoot. There was a lot of shit going on leading up to that moment. That was definitely a progressive statement. We were an all-Black cast.

THOMPSON: It felt like a moment when Hollywood became, I don’t know—

SANDERS: A little less sus.

This article appears in the Spring 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Hair: Tiago Goya using ORIBE

Makeup: Sara Tagaloa using MAC Cosmetics

Production: Dana Brockman

Photography Assistant: Zach Coco