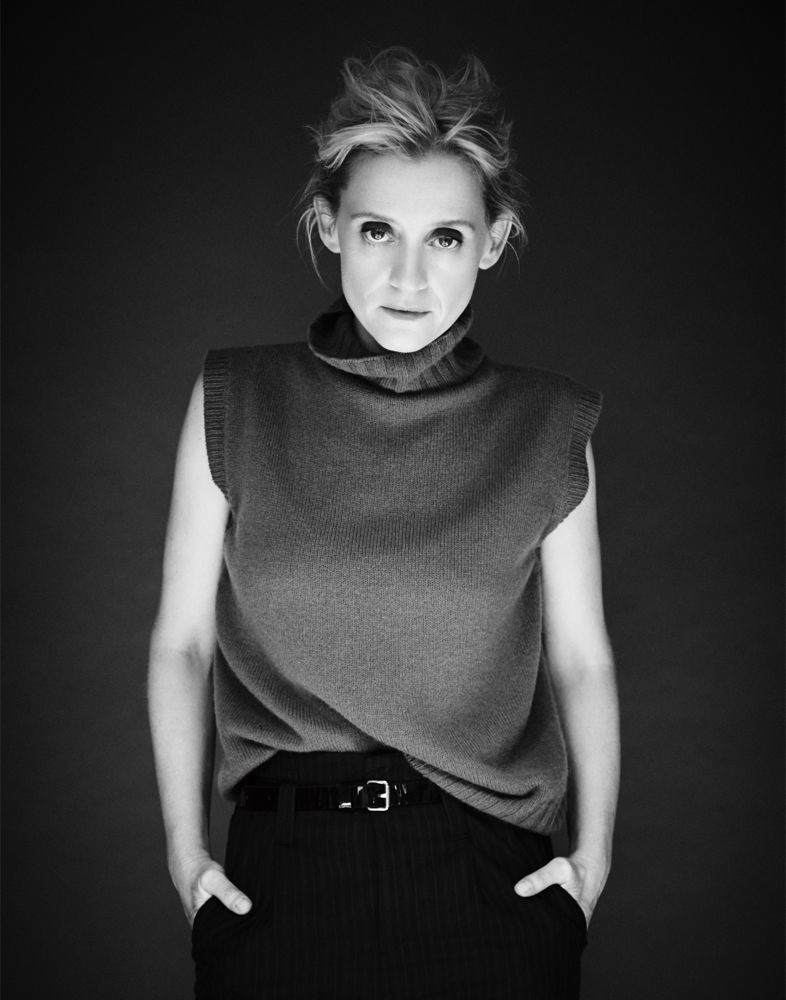

Anne-Marie Duff

ANNE-MARIE DUFF IN LONDON, AUGUST 2015. PHOTOS: MATT HOLYOAK/KAYTE ELLIS AGENCY. STYLING: NISHA GREWAL. MAKEUP: AKGUN/THE LONDON STYLE AGENCY. HAIR: NINA BECKERT/PHAMOUS.

In 1928, all women received the right to vote in Britain. In 1971, all women in Switzerland received the vote. This year, women will be allowed to vote for the first time in Saudi Arabia’s municipal elections.

The British women’s suffrage movement is often associated with well-to-do women: Leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union Emmeline Pankhurst, with her house on Russell Square; Margaret Haig Mackworth, the second Viscountess Rhondda, who tried to take over her father’s seat in the House Lords following his death; Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton, who protested under a pseudonym to avoid preferential treatment. But Suffragette, the new film from director Sarah Gavron and screenwriter Abi Morgan, makes a point of portraying of focusing on a cross-section of social classes. In the place of Mary Poppins‘ Mrs. Banks with her silk sashes and songs are London laundry workers Maud (Carey Mulligan) and Violet (Anne-Marie Duff). Orphaned as a child, Maud has been at the laundry since she was seven years old. She’s married now with a small child—a leap in stability compared to her past—but still under the thumb of her revolting employer. Violet is optimistic but downtrodden, with a good-for-nothing husband and too many mouths to feed. With Violet’s energy as the catalyst, the two women join their local Women’s Social and Political Union led by pharmacist Edith New (Helena Bonham Carter).

Born and raised in London, Duff has been acting since the late ’90s. She is perhaps best known for her roles as Fiona Gallagher on the original iteration of Shameless (where she met her husband, James McAvoy) and in British indie films such as The Magdalene Sisters and Nowhere Boy. In addition to Suffragette, which comes out next week, Duff just wrapped a new BBC television series From Darkness and is final rehearsals for the play Husbands & Sons at the National Theatre in London.

EMMA BROWN: How did you get involved in Suffragette?

ANNE-MARIE DUFF: I got a phone call asking would I meet with Sarah Gavron, the director, because she and Abi Morgan were planning to make a movie about the suffragettes. At that point, they didn’t have a locked script. They had a vague idea of what they were going to do, but nothing solid. I just went to have a chat with them and they said, “We would love to make a movie about the subject.” Like most people, I was astonished that it hadn’t been done. It seemed very exciting. Then I came to New York to do a play and suddenly got a phone call saying, “It’s all happening; let’s go for it.” By the time we got Abi’s brilliant script, I was really, really looking forward to reading it. It was just one of those incredible no-brainers.

BROWN: When you first met with Sarah and Abi, did they have an idea of the character they wanted you to play? When did Violet come about?

DUFF: Sarah didn’t talk too much about Violet. She said she had an idea about a woman who was deeply embedded within the cause, who was quite militant, but that was as much as they’d worked out at that point. It wasn’t until I saw the script that I thought, “Oh god, she’s gorgeous and so interesting and so alive and vibrant.”

BROWN: Violet’s preteen daughter works at the same factory as Violet, and some of the stuff she goes through is quite upsetting. Do you think Violet is willfully unaware of what’s going on or genuinely doesn’t know?

DUFF: It’s very curious, because there were scenes that were cut to that purpose. It was viewed that the audience wouldn’t understand how she could turn a blind eye, so we cut a section of the movie because of that. As the film stands now, she isn’t aware, so we have to go with that really. There was an element before where they have so little money that often sacrifices were made [but] because Violet is so feisty and so active, she’s a real dynamo, they were worried people would think, “She of all people would certainly defend her daughter.”

BROWN: You mentioned you learnt about the suffragettes in school. Did you learn about the suffrage movement as something that extended through all social classes or something that was primarily a middle class movement?

DUFF: That’s the great thing about this film, it does really focus on the working class and I don’t think that’s what we associate with that movement. We have a real blue stocking, upper middle class and upper class notion of the suffragette movement, and I suppose those were women who could afford to spend time campaigning or were in influential positions. But it is exciting to think that there were women—and also mind-blowing—below the breadline taking all those chance who were prepared to sacrifice everything for the notion of legacy.

BROWN: I know you studied at the Drama Center in London. What made you choose that particular drama school?

DUFF: I wasn’t a little girl who went to ballet class; I wanted to be an actor from when I was in my mid-teens, and it was perfect for me that kind of training, because it took itself very seriously. We had teachers from the Actors Studio and we studied Hagen; it was a real grown-up drama training, which is exactly what I wanted. I really craved that.

BROWN: I’ve heard that it’s more rigorous than some of the other drama schools.

DUFF: It certainly was when I was there. It’s had many seasons since because it’s a long time since I graduated. There were lots of very exciting actors there at that time and it was very hot, but it was tough training. Paul Bettany was the year below me. Helena McCrory was at the school around that time. Lots of great British actors.

BROWN: You’ve been working very consistently since you graduated, but was there ever a moment where you doubted your career choice?

DUFF: I think you should, really—just a moment where you assess what you’re doing and if it’s good. I love it passionately, but I did have a crisis moment about 15 years ago when I was working on a production of A Doll’s House. I literally thought, “I can’t do this. I don’t want to be a crazy person,” because it was affecting me so deeply, and I walked off stage. Another brilliant actor in the cast Paterson Joseph came up to me and he just looked at me and said, “There are 250 people out there who have paid a lot of money.” It was such a brilliant wakeup call because it made me realize it’s not about self-indulgence and it is a job and you’re there to do something for other people; it’s not just about your process. I thought that was extraordinarily helpful. It helped me achieve a level of what Mamet describes when he talks about wiping your feet on the doormat as you leave the theater—trying to have a little bit of separation.

BROWN: How did the rest of the production go? Did you go back on stage after that?

DUFF: I did. I was playing Nora and at the beginning of the play, Nora’s always eating macarons, so I just told a big, fat fib and I said, “Oh, I’m so sorry ladies and gentlemen, but I’ve just choked on a macaron and had to get a drink of water.” Of course I got a round of applause, which I felt terribly guilty about, but the rest of the production went well ironically.

BROWN: Did that experience affect the sort of roles you accept—do you try to take roles that are less involving?

DUFF: No, I tend to always go for those roles because I think they’re the most interesting characters. People at a point of conflict are always the most interesting stories to tell. I guess you just grow up and learn to think instead of just feel.

SUFFRAGETTE COMES OUT OCTOBER 23.