Film!

Andrew Rossi’s New Docuseries BringsAndy Warhol’s Private Diaries to Life

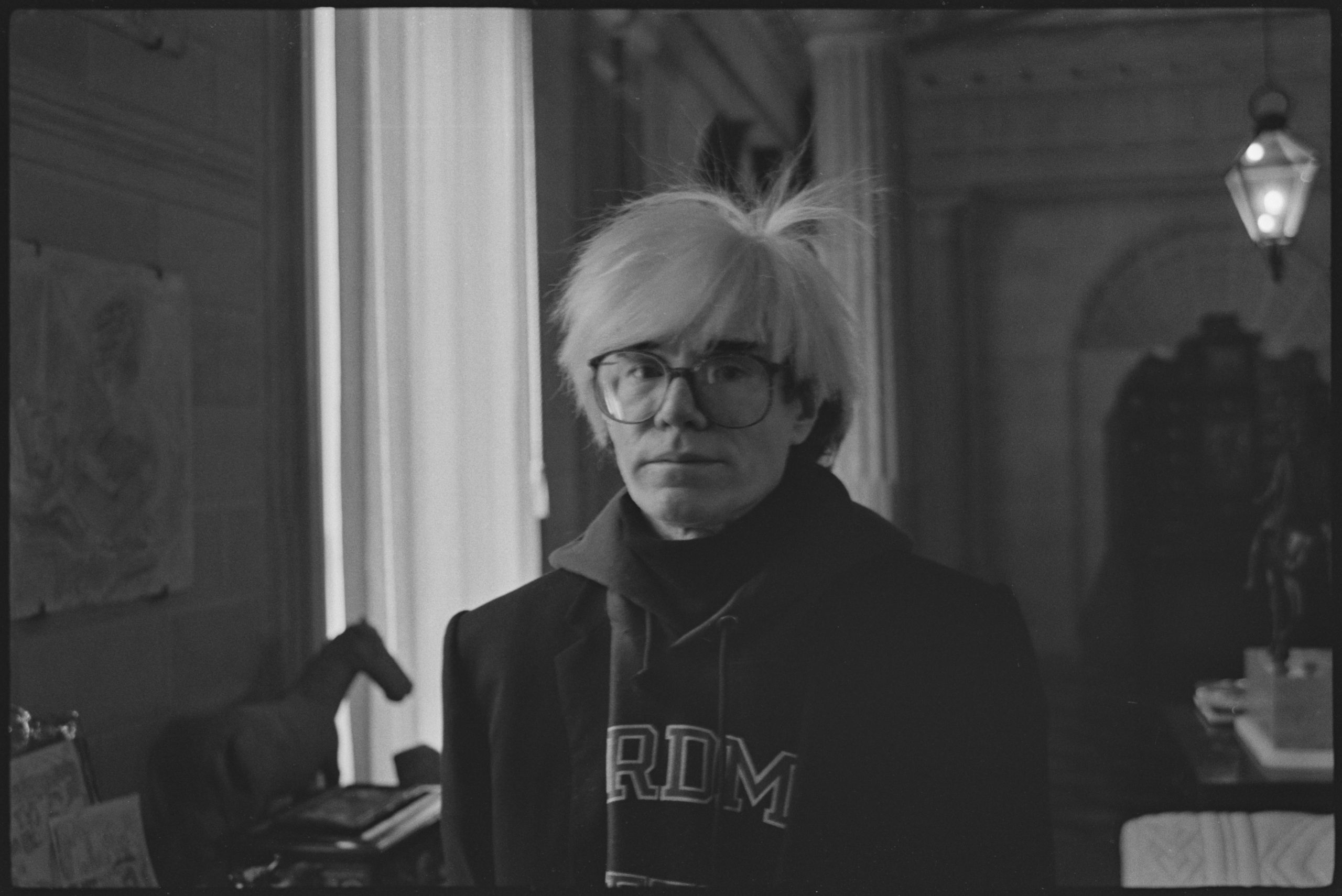

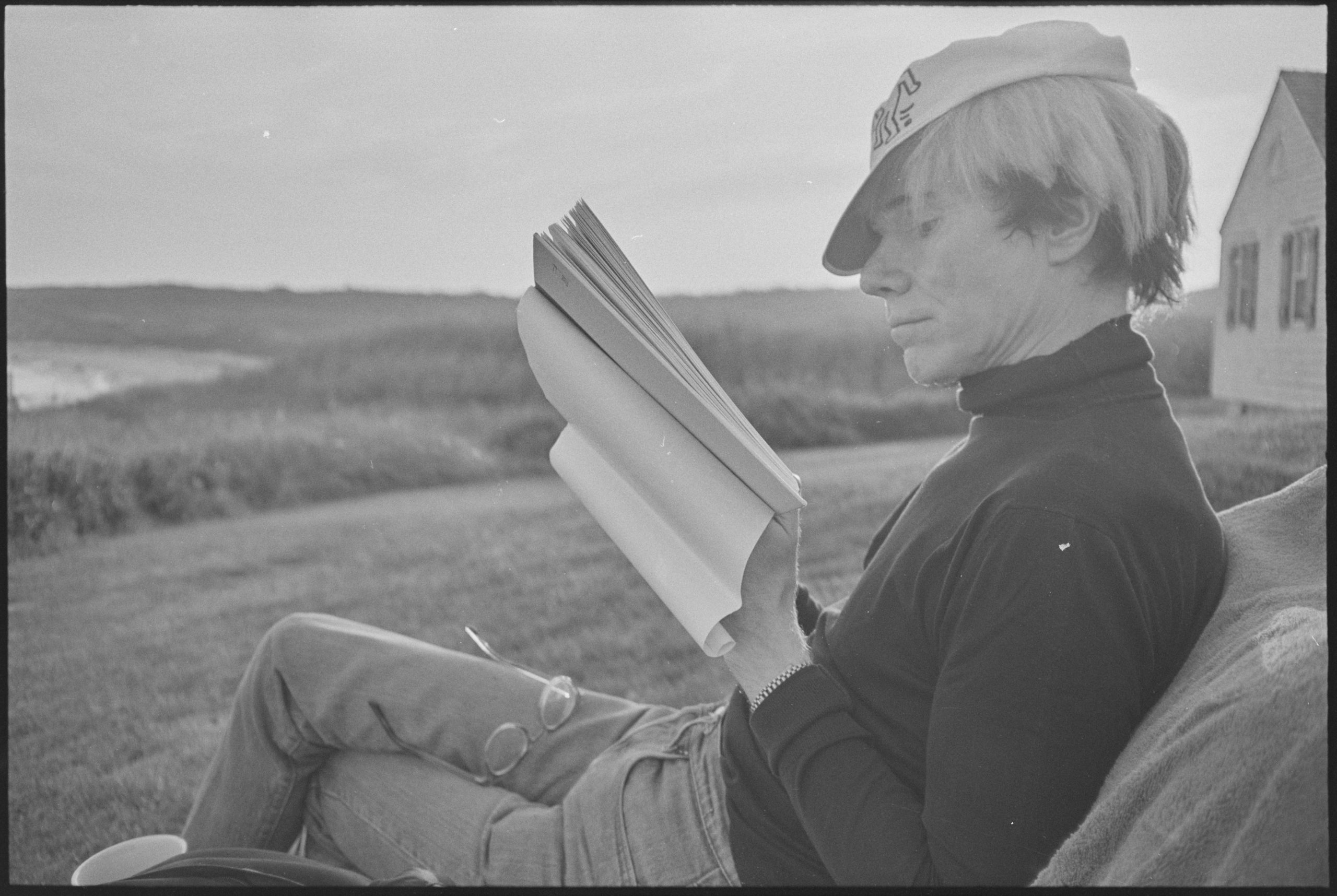

Brillo. Marilyn. A silver mop of hair. Few artists’ work is as thoroughly embedded in the zeitgeist as Andy Warhol’s. But despite his fame and ubiquity, we never learned much about the artist himself, or what went on in his uptown townhouse. 35 years after his death, we’re still chasing Warhol down, trying to arrange the pieces into a more complete picture.

One person who hopes to fill in the gaps in Warhol’s story is Andrew Rossi, the filmmaker behind revelatory documentaries including Page One: Inside the New York Times and The Gospel According to André. His latest project, The Andy Warhol Diaries, explores the artist’s self-doubt, relationships, and the dynamics among his eclectic circle of friends. The six-episode Netflix series is based on a book of the same name—a collection of Warhol’s diary entries compiled by his friend Pat Hackett. Five days a week at nine in the morning, Warhol would dictate his diary entries to Hackett over the phone, leaving her with more than 800 pages of personal notes after his death. After a protracted legal negotiation with Warhol’s estate, Rossi gained access to this trove. He trimmed the pages down, and paired them with exclusive footage, interviews with friends, and a bit of AI in order to paint what he hopes will be a definitive Warholian portrait—this time, of the artist himself.

———

SOPHIE LEE: Nice to chat with you today.

ANDREW ROSSI: Sophie, nice to meet you.

LEE: I’m excited we’re doing a Q&A, in Andy Warhol’s style.

ROSSI: That is amazing.

LEE: At Interview, Warhol hangs over us like a specter, watching what we do, and after watching the show, I feel like I have a better understanding of him. How did you get involved in this project?

ROSSI: I began making The Andy Warhol Diaries back in 2011. I had just finished directing the film Page One: Inside the New York Times about the media desk at The Times. My agent, Josh Braun said to me, “What’s next?” I have tried in my work to investigate icons—whether institutions or subjects—and I wanted to tackle another seminal force in our culture that looms large in our imaginations, but that we don’t understand so well. The Andy Warhol Diaries was the window into understanding the man behind the iconic mask. So, I reached out to Pat Hackett, and she was open to talking with me, but referred me to the Warhol Foundation. That set off a six year process of trying to negotiate the rights to The Diaries. But, the great thing about that is it gave me an opportunity to reread them and to really discover what I believe is a unique angle into Andy— focused on his love life and his queer longing, which comes through so achingly in The Diaries.

LEE: What was your view of Warhol before starting this project?

ROSSI: I grew up in the 1980s, with Andy as a hero. My father used to take me to galleries in New York City where I saw his work. I thought the repetition, the color, and the silkscreening were so fresh and fun. I watched him on Andy Warhol’s TV on public access cable, and he was always providing a safe space, or offering permission to be who you wanted to be. I was, figuring out my sexuality at the time in a very homophobic environment, that was very powerful. I viewed Andy as somebody who was very special, but who I didn’t know in some deeper, human way. I remember leaving high school on the crosstown bus, then walking up Madison Avenue and seeing The Diaries in a bookstore window and reflexively going inside and buying a copy because I felt it would be the key to understanding Andy. As a bisexual man, that was incredibly powerful. But it wasn’t until 2011 that I was on tour with Page One, reading The Diaries in my hotel room by myself, or in a coffee shop alone, that Andy’s voice emerged so intimately in my ear and in my heart. I thought, “Who is Jed Johnson? Who is Jon Gould? These people are such passionate objects of his affection. I want to know more.”

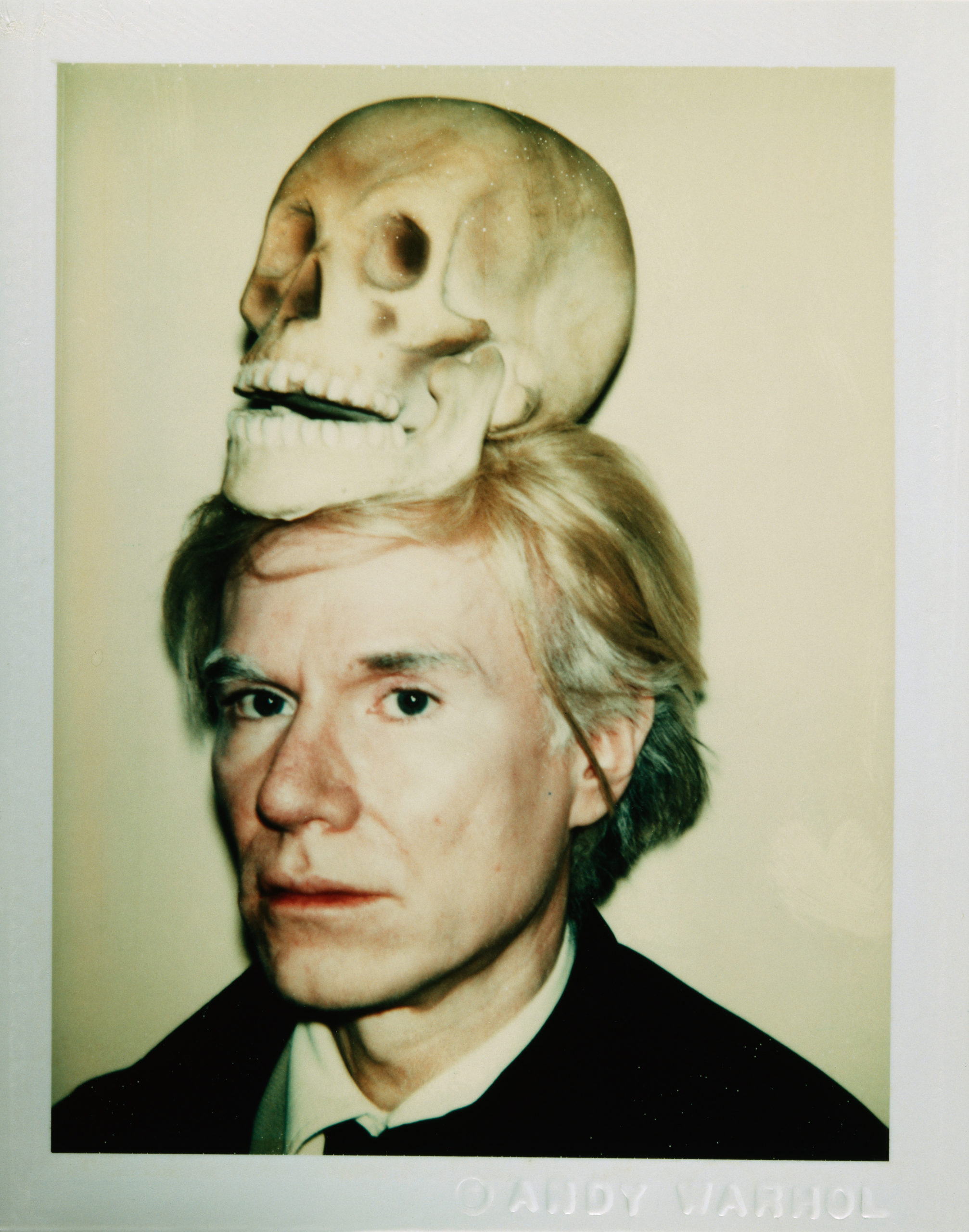

LEE: While I watched the series, I couldn’t help wondering what Andy would think of it, how he would feel about people knowing these intimate things about him. On the one hand, he’s very private. On the other, he really sought out an audience—even orally transcribing your diary entries is such an insane thing to do. Did you think about his response while making this?

ROSSI: Absolutely. The fact that he wanted them published after he died feels like a grand, final gesture, both personal and artistic. So, what is the meaning of that? Why does he want people to have this record, to know what he did for ten years once he can no longer be there to witness the reaction? I think there are multiple reasons. One is that, you know, he speaks very candidly about the people in his circle and the celebrities in his orbit. He says very scandalous things about them. He talks about their drug use. He talks about the way they dress, aspects of them that are not so flattering. But the most shocking thing he talks about have to do with himself. He reveals his vulnerability, his fear about not being as important an artist as Jasper Johns, not having the same auction price as [Robert] Rauschenberg. He talks about a feeling of emptiness, his search for spiritual meaning. His response to that is to try to fall in love with Jon Gould, and to put himself in a position that is very vulnerable.

LEE: I was struck by the real sadness that pervades this series. It shows a very tragic, human element of all these people’s lives who are seen as the epitome of glamour by people my age. Do you think this is a sad series?

ROSSI: The celebrity parties and the glamour are like a forcefield, or even a false flag, to distract from what The Diaries so poignantly describes, which is loneliness and longing. That forcefield hides a deep pain that stems from his feeling that he’s not attractive enough, and that he’s too awkward to be loved. I think we see Studio 54 and the fun of the late ‘70s and ‘80s with a nostalgia that is misplaced.

LEE: So many interviewees talk about this spirit that Warhol represented: “Come to New York City! It’s this amazing place where we can all discover ourselves.” How do you think you would have felt, as a kid who looked up to him, if he had shown more of that vulnerability?

ROSSI: Bob Colacello talks about Andy’s effort to make portraits of his neighbors in Pittsburg as a way to connect with a community that was homophobic and racist in the 1930s, like so much of the United States. He was trying to fit in with his artwork, and that was in some ways successful. When he brought those drawings to the Tanager Gallery in the 1950s, they were rejected out of hand because of their homoerotic depictions. I think young people today experience other forms of alienation. So much has changed for the better, but the feeling of not fitting in and being an outsider remains.

LEE: I loved the contrast of people who talk about him so familiarly, and the academics who speak about him in a very formal sense. How did you figure out which perspectives to rely on?

ROSSI: When I finished rereading The Diaries, I wrote scripts for each episode based on the diary entries that I thought revealed the most about his longing and his pursuit of romantic partners, as well as his aesthetic sensibilities. Then, I looked at the artwork he produced at the time and tried to make a bridge between what he was doing in his life and the work he was creating. That created almost a Venn diagram of who was where at the time—who was present at the Diana Ross concert, who knew Jed or Jon, and so on. I tried to figure out who could speak to the coded meanings in these paintings, related to what was happening in his life, who he was breaking up with or pursuing. In his Shadows and The Last Supper series, you can draw a line between the plot points in his personal life and the work that he creates. So, Jed Johnson and his brother Jay [Johnson] Jon Gould and his brother Jay [Gould] (another twin), were key. Bob Colacello is a brilliant writer who knew Andy so, so intimately. Christopher Makos, who introduced Andy to Jon, has so much insight into Andy’s process and love life. Benjamin Liu understood Andy’s effort to make peace with his homosexuality. All of these people know Andy in a way that others, “experts,” might not, because they were with him in those vulnerable moments.

LEE: Was there anything that you were delighted to discover through this process?

ROSSI: In 2017, I went to Amesbury, Massachusetts, for the estate sale of Harriet Gould, who was Jon’s mother. When Jon passed away, all of his personal effects were shipped from Los Angeles back to Massachusetts and they stayed in an attic in Harriet’s house until she passed away. The auctioneer told me that she knew what she was doing when she planned for Jon’s belongings to be auctioned off. There were paintings that Andy made for Jon, poetry that Jon wrote in the margins of his business documents, photographs of the two of them together and of Jon on the beach. Jon is the most photographed in the Stanford collection of snapshots. I felt such a sense of connection to that relationship and to Jon’s humanity. There were letters from Jon’s friends to his parents after he had gone blind in Cedars-Sinai Hospital in L.A. I knew that I had to investigate this relationship more deeply to understand who Andy was.

LEE: Everyone had such different takes on that relationship. One of your interviewees, when asked who Jon Gould was, she said, “I’ve never heard that name. I don’t know who that is.” Others said, “He was the love of Andy’s life.”

ROSSI: That was Jerry Hall. When I asked her what it was like after Andy broke up with Jed, she told me that he never had another boyfriend again. I said, “Well, have you ever heard of Jon Gould?” And she said, “Who?” There’s a certain theatricality to some of the interviews—if you read between the lines you can see that Jerry must have had some ambient knowledge of Jon, because he and Andy were companions and went out together, but that relationship was never viewed as authentic, because people compared him to Jed, and he was in the closet. Their love was seen as, perhaps, compromised. No one knew why Jon was really with Andy. Katie Dobbs, Jon’s dear friend, speaks movingly about Jon’s own journey to understand his sexuality. She said that Andy was the golden ticket to a side of New York he couldn’t even imagine having access to otherwise. But also, Andy protected to Jon. Jon moved into his townhouse, which was like a sanctuary for their love, and shielded Jon from some of the forces in the outside world. That comes through in Jon’s poetry. It also comes through in the sort of involuntary recoil that people like Bob Colacello and Pat Hackett have at the mention of Jon’s name. So, I think there’s a productive tension in allowing all those different perspectives to coexist, because that’s how people felt and continue to feel. My job, as a filmmaker, as a director and writer, is to weave those together and to let the viewer reach their own conclusions. Some people might feel that Jon was not the angelic figure that Jed was, and I can understand that. But I also think that Jon got Andy to dance. He clearly unlocked something in Andy that was vital.

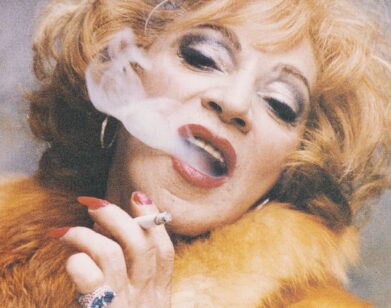

LEE: The same seems to be true of his relationship with Jean-Michel Basquiat. Some people say, “They were in love.” Others say, “Andy was like his mother.” How did you approach those less clear-cut relationships?

ROSSI: With Jean-Michel, there were important structural dynamics that I wanted to address. Andy was Jean-Michel’s landlord. He rented 57 Great Jones to Jean-Michel. He was a successful artist who invited Jean-Michel into his world, and always had, on some level, the upper hand, because of his professional prominence. That being said, he really loved Jean-Michel and their relationship represents another side of Andy, which Hilton Als describes as, perhaps, Andy as mother. He did take care of Jean-Michel, even though, as Paige Powell notes, he did not step in when Jean-Michel was suffering from drug abuse. So, it’s a textured relationship that also reveals many different points of view, and I tried to allow for that.

LEE: I have to ask about Andy’s AI voice.

ROSSI: It was a pleasure to work with Resemble AI, which is a start-up company that I contacted in 2020.It’s a challenge to capture Andy’s Pittsburg accent and his halting cadence with fidelity to the way he is as a human. But Andy said several times that he wanted to be a machine, that he painted the way he did in order to be a machine. So, there’s something very Warholian about hearing his aphoristic statements in a voice that is both Andy’s, and also some oracle. Resemble created an algorithm that I combined with Bill Erwin’s performance. Bill is an amazing actor who has a real approach to the poetry of ordinary language.

LEE: Where do you see this fitting into your body of work as a whole? You’ve done a lot of work that looks behind the veil of trusted institutions. Andy is almost an institution in himself.

ROSSI: I do feel that Andy Warhol is an institution in our culture. Investigating his humanity has a broader ethical value. 35 years after he died, people have a perspective on his queerness and his performance that shows how our values have shifted since same-sex marriage was legalized. There is much more sensitivity to the gas lighting that Andy experienced. He was trying to maintain functional, long-term domestic partnerships in an era when that was, as Alan Wanzenberg says, “bizarre.” There is so much to learn about our present moment by revisiting the past.