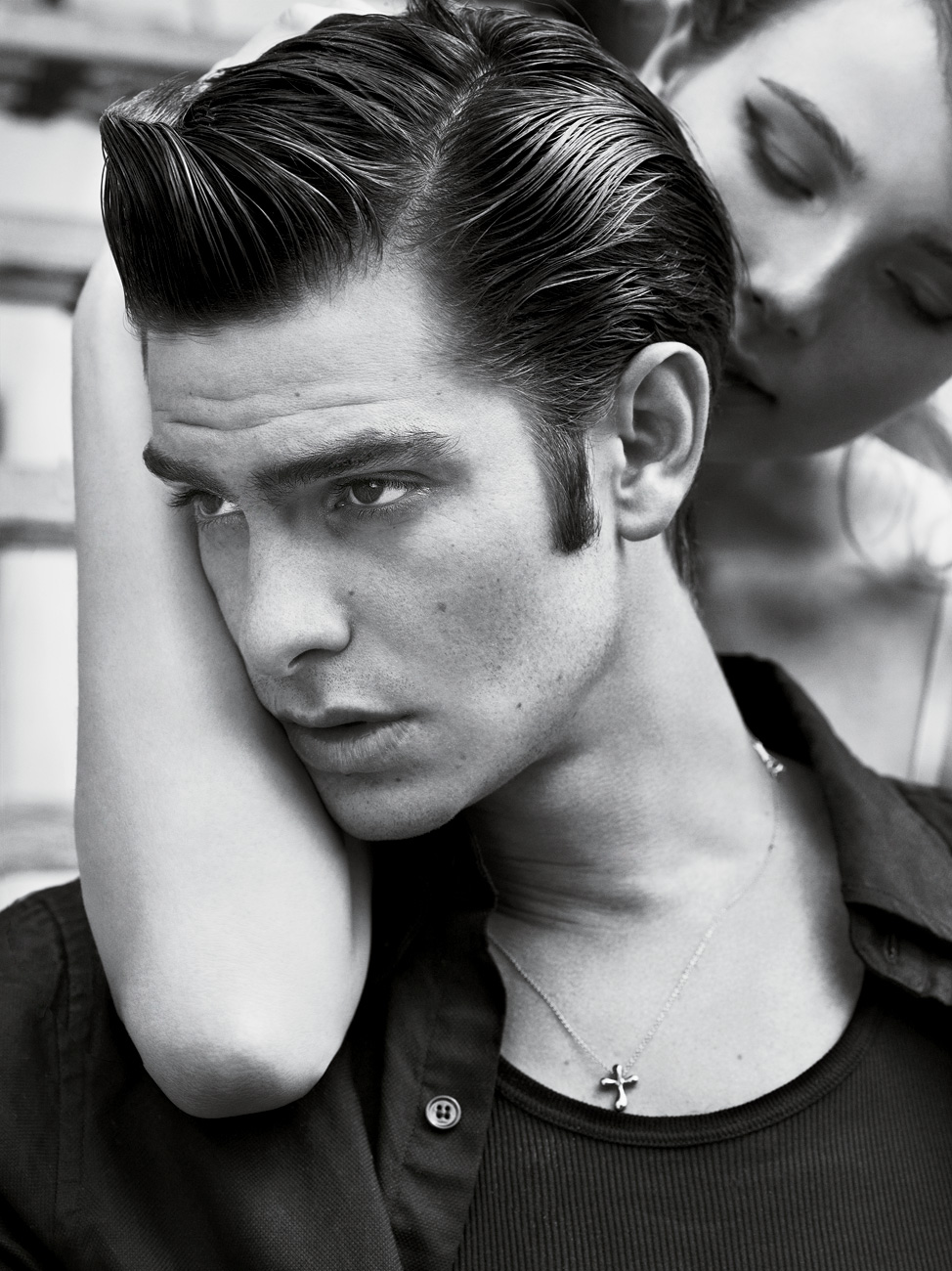

Andrew Garfield

America always seemed to me this foreign land that I imagined I could escape to if I needed to get away—and I think that came both from the fact that I was born there and from watching so many American movies when I was a kid.Andrew Garfield

Among the throngs of young British actors-made-good, there is something that sets Andrew Garfield apart—and it’s not the fact that he was born in Los Angeles, although that may not be entirely unrelated. Garfield’s distinguishing trait is distinctly un-British-actorly: that despite his prodigious drama schooling, stage training, and Anglo affinity for mining the “underneath” of things, it isn’t all about Olivier and the Bard for him. He still likes to stick his finger in a socket if the opportunity presents itself. It’s an instinct, or maybe even a propensity, that has apparently served the 27-year-old Garfield well thus far in his young career as a movie actor, which has included eye-opening turns as an ex-con in John Crowley’s acclaimed British indie Boy A (2007), as a student unengaged with the war in Iraq in Robert Redford’s Lions for Lambs (2007), as a sleight-of-hand artist in Terry Gilliam’s The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, as a robot in love in the new Spike Jonze short, I’m Here—and, this fall, as Mark Zuckerberg’s original Facebook friend, Eduardo Saverin, in David Fincher’s The Social Network, and as the male lead opposite Keira Knightley and Carey Mulligan in Mark Romanek’s new adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2005 novel Never Let Me Go. But perhaps the biggest socket that Garfield has plugged into recently, or the one with the most electricity coursing through it, is the newly rebooted Spider-Man franchise, for which it was announced in early July that he had been cast as Peter Parker, the aspiring photographer-turned-web-slinging superhero, taking over for Tobey Maguire.

The first installment of the new Spider-Man, to be directed by (500) Days of Summer’s Marc Webb, is set to begin shooting later this year. But before then, and with The Social Network and Never Let Me Go set to hit theaters, Garfield sat down recently in New York City with Gilliam—who was in town to direct a webcast of the band Arcade Fire’s performance at Madison Square Garden, which opened with a skit featuring Garfield that portrayed the group as robots controlled by Gilliam—to discuss Garfield’s rise, what it means to slip on those red-and-blue Spider-Man tights, and why, for someone who was raised in England and weaned on British theater, he has so many uniquely American dreams.

TERRY GILLIAM: Do you think acting is nature or nurture for you? Were you born an actor? Or were you nurtured to become one?

ANDREW GARFIELD: Gosh, I’ve never really thought about it like that. I think I could debate either side. I suppose acting was probably what I was always going to do, and I just wasn’t aware of it until I watched Teen Wolf [1985] and Teen Wolf Too [1987], and then I got inspired to do something with meaning . . . [both laugh] I wonder if irony will come across in print? Maybe not . . . But, seriously, I don’t know. It’s difficult because you don’t want to reduce yourself to such an archetypal personality that was born to act. I just think I’ve always been sensitive and had difficulty containing my feelings, and I’ve always searched for outlets for that, because otherwise those feelings come out in chaotic ways that aren’t always great. So I think I was searching from the start of my conscious life for some kind of constructive way to work through my feelings, and I found acting.

GILLIAM: Did anyone ever suggest any alternative outlets for that sensitivity—like getting another kind of proper job?

GARFIELD: Well, when I was 6 I thought that I wanted to be a musician—like a singer-songwriter. That’s what I romantically envisioned for myself. But in reality the experience of getting into music was just the opposite. My parents signed me up for classical guitar lessons, which made for two years of the most depressing Wednesday evenings. My teacher was this classically trained Spanish-guitar guy who kind of left me cold. Instead of learning how to play the kinds of songs I wanted to play, I was learning these classical pieces. Even my teacher’s attempts to teach me some Beatles songs didn’t quite connect. So I probably rebelled against that by never touching a guitar again. I was also into gymnastics when I was younger. I remember having a horribly traumatic experience where this fat guy sat on my back while I was doing the splits, and I was looking for my mother in the group of mothers on the sidelines, but I couldn’t find her. I remember sitting there, watching all of these kids do cartwheels—it just looked terrible to me. I envisioned myself getting sick, and worried about what all of the other kids would think, and what it would be like to not have friends for the rest of my childhood. All of those thoughts were running through my head as I was searching for my mother and I couldn’t find her. But then I eventually found her, and she came to the rescue like all good mothers do. This was in the early stages of my illustrious gymnastics career. I have to say, though, the first time I ever did a backflip was one of the greatest moments. It was kind of incredible. I felt superhuman for a second. I tried to carry on to achieve that again, but it takes a lot of work to feel superhuman.

GILLIAM: Did you ever have any proper jobs, though, before you became an actor?

GARFIELD: Oh, yeah. The first job that I would consider proper was when I worked at Starbucks. That was when I first moved to London from Surrey, where I was brought up, and went to drama school at Golders Green. I went up there because I thought I would move into a house on my own and be independent. I was 17—I thought this was a great idea. I moved into this massive, empty house, and I thought I would get a job, so I walked into the Starbucks around the corner and somehow convinced them to hire me. I was actually really excited to work there. There was a very American, romanticized idea that I had in my head about what it would be like to work in a coffee shop. I thought of coffee shops as the kind of place where you met really smart, interesting, quirky girls with thick, black-rimmed glasses. But it didn’t turn out that way at all. I ended up being pursued by this girl who was very cool, but she just wasn’t my type . . . It was a personality thing more than anything.

GILLIAM: Because she was unattractive. Let’s just be honest about it. [laughs]

GARFIELD: Well, no. She was very cool. She just wasn’t my type.

GILLIAM: There you go—she was ugly.

GARFIELD: [laughs] I will not say that because I don’t believe anyone is ugly. How’s that?

GILLIAM: Oh, god!

GARFIELD: [laughs] She really was the coolest girl.

GILLIAM: So do you think you had this romanticized vision of things because you were born in America and there is some romantic thing deep down in your DNA?

GARFIELD: Yeah, I think so. America always seemed to me this foreign land that I imagined I could escape to if I needed to get away—and I think that came both from the fact that I was born there and from watching so many American movies when I was a kid. I was brought up on American films.

GILLIAM: You were born in L.A. How old were you when you left?

GARFIELD: Three.

GILLIAM: So America probably seemed like this special, ethereal world that you inhabited before you moved to Surrey.

GARFIELD: Yeah, absolutely. I think my dad was also always very romantic about America. He romanticized the period in his life when he lived in L.A. He still talks about it very fondly. So it’s nice that I’m now able to spend some time in L.A. and go back and forth between there and London. I think that kind of soul kiss, that California thing, is something I’ve always dreamed about and been drawn to. It somehow calls to me—and I think the great cinema that has come out of America is certainly part of that.

GILLIAM: What did your father do when he was in L.A.?

GARFIELD: He was an entrepreneur. He was in the business of selling designer lampshades—high-end stuff that was bought by small retailers and boutiques.

GILLIAM: Were they the kind of lampshades that people put on their heads at parties?

GARFIELD: I’m not sure, although, if that were to happen, then he would probably have been the one with a lampshade on his head. [laughs] But, yes, they were lampshades—things that shade lamps.

GILLIAM: What was your first acting job?

GARFIELD: It was a play, a stage version of the Ken Loach film Kes [1969]—the one about the kestrel [based on the 1968 novel A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines]. I was 20 years old. It was at this great theater, the Manchester [Royal] Exchange, which is in the round.

GILLIAM: How did you get it?

GARFIELD: The casting director, Camilla Evans, was kind of going around doing her drama-school duties, and seeing all of the desperately aspiring and needy people like myself who wanted so badly to be able to do the job of their dreams for a living. I think she was trawling through and saw me and thought I’d work in the play—and things sort of went from there.

GILLIAM: How’d you get the part in Redford’s film, Lions for Lambs?

GARFIELD: Again, it was just a good-fortune thing. I was doing a play in London at the [Royal] National Theatre. It was this great play called Chatroom. Stephen Daldry’s assistant came to see me in it and told Stephen to come see it. So he was screen-testing people for this film he was doing at the time that never got made, and he called me in. Eventually the tape of my test went to Avy Kaufman, who is a fantastic casting director, and she was casting the Redford movie and brought me in. Things kind of went from there. It was amazing spending time with Redford while we were making Lions for Lambs. Just incredible. But there was a period where I wasn’t getting much work before that. I remember talking to this woman, Jane Hazlegrove, who played my mother in that first play I did. She was such an incredible matriarchal figure—this strong, talented, passionate woman. She said to me, “You’re going to be fine. You’re in the right job. You’re going to work for the rest of your life, I promise you. The last time I said that to someone it was my friend Jude Law.” Being an impressionable 20-year-old at the time, I was like, “I totally believe you!” But then I didn’t work for a good period of time after that, and I was like, “Damn, Jane! You gave me this false sense of security.” I was feeling good about myself and then the harsh-reality tank came rolling in.

GILLIAM: So how did you respond to not working?

GARFIELD: Well, I had to develop certain defense mechanisms very, very quickly, and figure out ways to stop feeling defined by whether or not someone was offering me a job opportunity. I realized that after finding this thing that allowed me to express myself—acting—and being encouraged by a few people that I could do it, I had kind of grabbed onto it and dug in my claws in a way that was maybe a bit unhealthy. I allowed myself to get into a headspace where I lived or died by what I achieved in this particular field—which is not great when you’re not getting work.

GILLIAM: And once you start doing that, it’s difficult to know what you are when the work isn’t there. Who are you? What do you become?

GARFIELD: Exactly. I think I’ve gotten better about it, but at first it was shocking. There was this feeling of emptiness, of purposelessness, when I wasn’t working. I’m sure you feel the same way when you finish a film and go on to the next one.

GILLIAM: I think it’s worse for actors, though, because people have to choose you. As a director, I get to choose the actors, but most of the time, actors have to be chosen in order to work.

GARFIELD: Yeah, I guess. But on the flip side, I have to remember that I didn’t have to become an actor. I didn’t have to put myself in this position. If I’d wanted to have autonomy—if that was what I was after—then I could have chosen another profession.

GILLIAM: What do you think you would do if you weren’t an actor?

GARFIELD: If I’d been exiled from SAG and Actors’ Equity? If I’d been banished?

GILLIAM: I’m trying to think what you could be . . . A clown maybe?

GARFIELD: A street clown? A juggler? That would be cool. I’d probably go to school. I’d travel. I’d go wandering and get lost for a minute, like Jack Kerouac. And then afterwards, when I realized it was all vacuous and vapid and meant nothing to me, I’d probably take up photography.

GILLIAM: There you go. Phew!

GARFIELD: How about that? [laughs]

GILLIAM: I think that might work, thankfully, because things haven’t been going very well for you lately.[laughs]

GARFIELD: I’m very happy at the moment. Everything is great. As an actor, one is so appreciative when one is working. I think I am lucky that I have the opportunity to work. I mean, as you were saying about having that total dependence on an external validation . . . And just being a whore, really—a prostitute for hire, which I guess is the most cross but maybe the most honest way to describe it. I had this quiet moment on the plane recently. I was sitting there watching a really bad film and suddenly I went melancholic. I don’t know why. I was like, “Well, all of this means nothing, really, if you look at it a certain way . . .” But those moments are kind of important, because they make you go, “Well, what is kind of great? What are the actual, tangible things I can focus on?” And that really makes you want to define yourself outside of this job—and beyond the validation you do get or don’t get from working.

GILLIAM: You told me when we were in London that you’d always dreamed of playing Spider-Man.And now, all of the sudden, your dream has become a reality and you’ve actually gotten the job playing Spider-Man. Are you sure it’s not a hallucination? Or that people aren’t just toying with you because they know your weakness?

GARFIELD: [laughs] I don’t quite believe it either. When I found out about being cast in Spider-Man, it was like this bubble developed around me. I was floating in it for a while. And then, suddenly, it evaporated, and I was like, “Well, I’m just an actor. I don’t get to actually be Spider-Man.” But maybe I’ll have moments where I’m convinced that I am and those periods of fantasy will get me through.

GILLIAM: It’ll be interesting to see how the reality of playing that character compares with the fantasy that you had when you were younger.

GARFIELD: Yeah. I think it’s going to be a little bit more complicated than what I imagined. And, of course, I’m going to feel a great pressure, which might be one of Peter Parker’s great struggles, in having to live up to this thing that he is supposed to be or symbolizes. It will be interesting. I think the more I can tie into my own reality, the better and more enriching it will be for everyone involved.

GILLIAM: It’s interesting, because playing Spider-Man is different from playing most parts. It’s a role you’ve fantasized about for a very long time, and, generally speaking, when you’re offered a part in a movie, you haven’t thought about it in that way before.

GARFIELD: Well, I do just want to be an actor. The thing I get out of it is actually doing the job and inhabiting the world and the role—and I mean that genuinely. That’s what I’m in it for. If I can keep losing myself—and finding parts of myself—in other people’s writing and direction, then that’s all I can really ask for. That’s all I want, to keep losing myself.

Terry Gilliam is a film director, screenwriter, producer, and former animator.