On Grief

“Growing up in Melbourne, I was aware of Nick Cave in a sort of peripheral sense,” explains director Andrew Dominik of his relationship with the Australian rock icon. “He was like the dark prince of Melbourne, a really galvanizing figure: ultra-cool and kind of dangerous.” It wasn’t until Dominik began dating Cave’s ex-girlfriend (the subject of the 1988 song “Deanna”) that a series of phone calls established a rapport between the two: “I didn’t really want to like him, because he was my girlfriend’s ex, but I couldn’t help it. … Over the past 30 years we’ve just gotten closer and closer.” Dominik cast Cave as a singer in his 2007 film The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and Cave in turn wrote the film’s score.

Last year, Cave’s 15-year-old son Arthur died unexpectedly in an accident off the coast of his hometown of Brighton, England. “I’ve been a part of the general rallying around the Cave family in the aftermath of Arthur’s death,” Dominik tells us. Though his latest film, One More Time With Feeling, deals frankly with the grief felt by Cave and his family, it was not intended to be a film about loss, rather it was loosely conceived as a performance documentary showcasing the musician’s latest album Skeleton Tree, and as a strategic means of shielding a bereaved Cave from the media glare—an improvised, practical response to his professional concerns. “The film kind of took shape as it went along,” says Dominik. “I always knew that it had to deal with Arthur. … We’re sort of circling around this tragedy: around and around until we eventually get close to it and start to deal with it directly.”

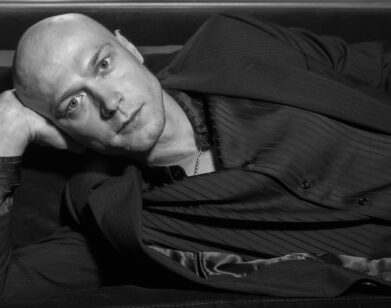

Released in 50 theaters across the U.S. as a “one night only” event last night, with more screenings to come around the world, One More Time With Feeling is an abstract exercise in portraiture, which, Dominik readily admits, defies narrative convention. “I knew the movement was going to be a collection of fleeting moments that are contrasting the external noise of the world that he’s in with this internal confusion and pain,” he shares. Shot largely in black-and-white, the film was screened in both 2D and 3D, an aesthetic experience that the director emphasizes as essential to the film’s narrative looseness: “3D is something that, in my opinion, switches off that patent recognition part of your brain. When you watch something in it, you don’t really want to do the work of following a story. Things can kind of sink into you in a more impressionistic fashion.”

We recently caught up with Dominik over the phone to discuss the film.

FRANK CHLUMSKY: I know that Nick Cave approached you to make this film, and it was in part to keep himself away from the press in the wake of this tragedy. Were you hesitant about embarking on this project? Did you fear that even he might not know what he was getting into?

ANDREW DOMINIK: I had no idea what I was getting into. I said yes because Nick asked me. I wasn’t sure that he was necessarily making good decisions. There’s a part of me that even thought, “Are we somehow exploiting a death to sell a record?” I think he had similar concerns about it himself. When you consider the trauma that’s at the center of the film, everything else pales in significance: the songs, the career, any of that sort of stuff. But my instinct in doing that was that I just wanted to help if I could. As a friend, I wouldn’t go into the areas with him that I go into as a filmmaker, but I felt that he wanted me to be a director rather than a friend. At the time it was very amorphous what the film would be. I knew that they were going to play the eight songs from the album and that I had to shoot them, which is fairly straightforward and is initially what he asked me to do. It wasn’t going to add up to much. It was just going to add up to about 30, 40 minutes worth of film.

CHLUMSKY: In that initial conception of the project, was there any idea that it would include interviews at all, or was it all going to be performance?

DOMINIK: It wasn’t decided. I was like, “We’ve got to shoot some other stuff.” He was like, “Well, I could talk about the songs.” And I thought, “Well, I don’t want to get into this kind of ‘Professor Cave,’ giving me a lecture on each song before he sings it.” He was very reticent that I should interview him. But then—just before we started—I got the idea of recording some voiceover. I had a look through Nick’s songbooks, his lyricbooks, and there were all these beautiful things that he’d written that were lost songs. I thought that there could be a place for that kind of thing—a way to give us access to his inner life. I would give him topics of conversation, things to talk about. We’d talk on the phone, I’d tell him what I wanted, and he’d record something on his iPhone and I’d wake up and it’d be in my Dropbox the next morning. I had about three hours of this stuff.

CHLUMSKY: Do you think that for Nick having the crew there was a kind of welcomed distraction?

DOMINIK: Yes and no. I don’t think that Nick finds the process of being filmed in any way comfortable or fun. He really doesn’t, and he’s very conscious of the camera. Warren [Ellis, Nick Cave’s bandmate in the Bad Seeds] forgets that the camera’s going almost immediately. As soon as he’s got something else to do, he just tunes us out. Nick was never like that. It took a lot for him to forget that we were there. In spite of what I said earlier, I think his instincts were really good. I think the reason that I finally said yes was that I understood that it was a really unique situation to be in to be able to make a portrait of somebody who’s undergone such a shattering event, and so soon after—it was within six months of Arthur’s death that we started shooting. Nick is still absorbing the initial shock of the blow. Both Nick and Susie [Bick, Cave’s wife] give us some insight into what it’s like to grieve. That was the criteria by which I used stuff in the movie. I wasn’t sort of looking for displays of emotion, but I was looking for things that they had to say that give you an insight into what their lives are like, in a practical sense. On that basis things have been included in the film or excluded from the film. A lot of people don’t necessarily suffer losses like this until later in life, but everybody’s going to lose somebody that’s important to them. If the film is going to have any value beyond its moment in time, it’s because it deals with that in a way that’s honest.

CHLUMSKY: At one point in the film, Nick expresses discomfort with being what he calls “an object of pity.” How do you reconcile that as a director?

DOMINIK: I don’t feel pity for Nick—not like he’s talking about. I feel empathy for him. Pity is difficult for anyone to deal with, I think. He doesn’t need our tears. I think he wanted me not to be afraid of his feelings or the situation. And he feels wounded, he feels diminished. I think he feels that many things that were incredibly important to him before Arthur died are no longer important. But he wants to be able to be seen not as just a symbol for a tragedy. I’m sure part of the fascination with the film is voyeuristic—that we go to see somebody who’s been struck by lightning. You know, “There but for the grace of God go I.” But I think the film gives you a picture of a person. It gives you a complete picture. I’m not sure if you come out of the movie feeling like he’s an object of pity. Did you?

CHLUMSKY: I wouldn’t say so; like you said, it wasn’t grief porn. That’s interesting, too, because it seems like there’s a notion that documentary filmmaking is often by nature exploitative, or that the director’s vision is always going to supersede the intent of the subject—at least when it comes down to the edit. With this, did Nick have control over what went into the final cut?

DOMINIK: I made this deal with him to relax him while we were shooting: basically I could ask him anything and I could shoot anything, and in return he could cut anything out of the movie that he didn’t like. But he didn’t end up exercising that right, if you like. There were things about the movie that he didn’t necessarily feel comfortable with, but I think that he felt if he were going to occupy some authorial role, he was going to have to be the one who’s talking to you now instead of me. So he decided to just leave it, whether he was comfortable with things or not.

CHLUMSKY: Were there moments in the footage that were more emotionally charged than the film let on?

DOMINIK: Yeah, there were. There were times where I would try to steer the subject towards Arthur. There’s one moment in particular I can think of with Susie where I brought it up, and you just see her start to shake. This black hole opens up in the room; it’s a terrible feeling. It’s not a feeling of sadness or anger; it’s this awful sort of hollow emptiness. I felt that when I pushed the conversation, when I made it be present in the room, there was something invalid about that. I didn’t feel good about it. That’s a dilemma, because grief is something that goes in waves. When somebody’s out of it, you don’t want to bring them into it. It’s going to get on them soon enough.

CHLUMSKY: To what extent was Susie involved in the post-production?

DOMINIK: Had Susie wanted me to remove anything, or had Earl [Cave, Bick and Cave’s son and Arthur’s twin] wanted me to remove anything, I would have done it, because their feelings are more important than mine in this instance. And that’s an unusual feeling for me as a director, because usually it’s about what I think. She didn’t like any of the stuff with her in it. Susie’s genuinely a modest person—it’s not like a false kind of modesty. She did it because Nick and I wanted her to do it, but she just didn’t really feel comfortable. It was really hilarious when I showed it to them. Nick hated everything where he was talking to the camera, and she hated everything with her. But they liked each other. They thought what each other had to say was great. They allowed me to keep the film the way that I wanted it, even though Nick hates the end.

CHLUMSKY: Initially, the film was shown for one night only in September after the Venice Film Festival. Why was that? And why bring it back now?

DOMINIK: I think originally the idea was that they were just going to play it live, and they do this thing in England where a band plays and people can buy tickets to see them in a cinema. They made some deal with the distributer to release it like that—it was an album launch. I really liked the idea of it only showing once, I thought it was kind of perverse and fantastic, this idea of a completely disposable movie. But, you know, people saw the film and reacted really strongly to it. A lot of people hadn’t seen it, so it’s been brought back I guess by popular demand.

CHLUMSKY: Prior to this project, had you had any interest in shooting a documentary?

DOMINIK: No, not really. But I had a feeling I was going to learn something by doing it. It’s a wonderful thing to go to work and have no idea what you’re going to do that day. I’m really pleased with the film. It was shot in 10 days with no plan. It’s a completely improvised movie where I just had to follow my instincts about what to shoot, what not to shoot, and whether these things could be brought together in a way that would make something that would be moving. It was a great experience. Even from the point of view of not being in control. I mean, you see what happens when I make an attempt to stage something in the beginning of the movie; he becomes completely uncooperative. I was in service of something else. It was a really fantastic experience. It sort of changed the way that I wanted to work.

CHLUMSKY: Do you think you’re going to be able to bring that looseness and improvisation to your filmmaking in the future?

DOMINIK: I think so. I do that a little bit on my films—you always try to keep the things living. Half the time you’re following your instincts and the other half of the time you just have to see where they’re leading, so you let things go. But on this film I didn’t have the luxury of doing that. I just had to go. I just had to shoot it. I think I’ll be a bit braver with that stuff in the future.

CHLUMSKY: Do you think you’ll go on to shoot more documentaries?

DOMINIK: I don’t know. But I certainly really like the experience. Do you think the film is really a documentary?

CHLUMSKY: I was asking myself that as well. I was sort of inclined to call it a work of non-fiction. Maybe the only thing “documentary” about it is that there are interviews. What would you call it?

DOMINIK: I don’t know. It’s like a poem or something. Or maybe it’s more like an essay film or something. It does a weird switch of being abstract and then becoming more traditional as it goes along. I guess the idea was to do something that had a barricade feeling, but could give you insight to the inner life at the same time. It was really surprising, because the shape of it was not something that was planned; it was something that was arrived to by investigation I guess. There’s something very exciting about working that way, because there’s more of a chance to discover. I think the film lives.

CHLUMSKY: It reflects Nick’s changing worldview: at the beginning he says that he doesn’t really believe in a narrative to life anymore.

DOMINIK: I think that’s the business of art in general—to bring meaning to things that are chaotic. The way we do it is by telling ourselves a story. Even before this thing with Arthur happened, Nick was trying to abandon narrative in an attempt to have a more direct expression: a collision of images or ideas. I think what you see in the film is that he’s still struggling the whole way to create a narrative, to get his arms around the whole experience. Whether he thinks that he’s abandoning it or not, I’m not sure that he really is.

FOR MORE ON ONE MORE TIME WITH FEELING, VISIT THE FILM’S WEBSITE.