Alex Karpovsky’s Lab Life

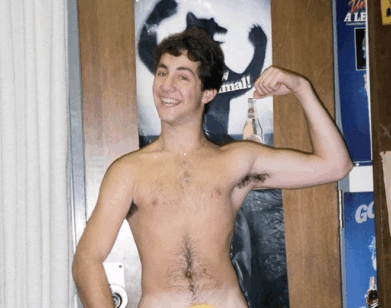

ABOVE: ALEX KARPOVSKY, SHOT AT HOTEL AMERICANO IN NEW YORK. PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER GABELLO.

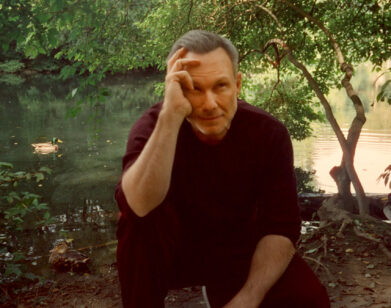

Anyone who knows Alex Karpovsky’s work probably thinks of him first as a comedic actor. His roles in Mike Birbiglia’s Sleepwalk with Me and Lena Dunham’s Girls and Tiny Furniture, plus a slew of shoestring-budget indie comedies, have more than established his comfort with humor (especially of the slightly-uncomfortable variety). But Karpovsky’s range—both with genre and in his multihyphenate capacity as a writer-director-producer-editor who acts, too—is remarkable. Those who conflate Karpovsky with Jed, his dickish character in Tiny Furniture, will be thoroughly surprised by his latest project, Rubberneck, which he directed and co-wrote and in which he stars as Paul, a lonely, serious scientist living in Boston. When Paul has a fling with a new co-worker, he becomes obsessed with her—a fixation that builds and finally culminates in unexpected, irreversible events that force Paul to confront long-suppressed facts about his own past.

Rubberneck is a moody, suspenseful drama that marks Karpovsky as a director to watch—and on the acting side, it seems his star is already on the rise, with six films coming out this year and a role in the Coen brothers’ upcoming Inside Llewyn Davis, alongside Carey Mulligan and Justin Timberlake, due out next February. We talked to Karpovsky this week in anticipation of Rubberneck‘s Tribeca Film Festival debut this evening.

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: This is your fourth feature, but the first thriller. How was that different for you from doing the documentary and the comedies?

KARPOVSKY: Well, Rubberneck has nothing to do with comedy, nor does it follow comedic people. So it’s very different in the genre respect. My favorite types of movies to watch as a viewer are thrillers—I really have a soft spot for them, I love them. Especially psychological thrillers. So I’ve always been interested in making one. The opportunity to do it in Boston manifested a while back.

SYMONDS: How did that happen?

KARPOVSKY: I’m from Boston, and I get easily overwhelmed in New York, so I go to Boston and stay with my parents for a few months at a time to write, or edit, or just to cry. During one of these visits, I hung out with Garth Donovan, who is a filmmaker up in Boston and also a thriller lover. We just sort of started throwing ideas against the wall, what could we make with our resources in Boston. While we were doing our own projects, he had a movie at South by Southwest and I was working on other projects, we were nibbling on this in our free time, Skyping and Gchatting, and finally we got to a place where we were ready to make it.

SYMONDS: Is it different making a film in a place where you grew up as opposed to a place you came to live? Did you feel kind of like “you can’t go home again” while you were scouting locations?

KARPOVSKY: I understand why you bring that up. I try to play a character that doesn’t have that much in common with who I really am. [But] during the location scouting in Boston, where I did spend 25 years of my life, it’s just so saturated with memories and associations, and it’s really hard to see many environments as unobjective. I had to try, to the extent that I could, try and de-filter some of these locations and feelings, which is impossible to do, but I think I made some kind of progress. The fact that the movie is set in a scientific laboratory, which I didn’t grow up in, and a lot of it is set in the Cambridge area, which is different from where I grew up—it allowed me to project what I wanted to project onto the character in the story without being distracted.

SYMONDS: I wanted to talk to you about the lab, actually. There should be more thrillers set in labs. There’s something about the scientific method that—because it’s very methodical—allows for those eerie undertones. Those images of Paul petting the guinea pig are so unsettling, even though it makes total sense that he needs to do that as part of his job.

KARPOVSKY: I think there’s something unnerving, or can be accessible to a feeling of unnerving-ness in a scientific environment, as well. From our first meetings and brainstorms, one thing that as pretty clear was that both Garth and I wanted to make a thriller that was very subtle, muted, character-driven, slow-burning. Not a movie that had a lot of plot twists and turns, or more story-driven. We didn’t want to make a suspense thriller or action thriller, nor do I think we could have, given our resources. We wanted to make something much more psychological and character-driven.

Going back to your question about the laboratory, my dad is a scientist; I grew up in the scientific community in Boston. It’s a massive generalization, but I have found that a lot of scientists tend to be introverted, reflective, and meditative. It somehow felt like a good fit for a movie that was so character-driven and introspective. That sort of seemed to make sense, rather than setting it in a gym, or something. We thought about it for a while, but it has a very different tone, obviously. A lot of the work that these scientists tend to do is solitary.

SYMONDS: It’s so incremental, too, which I think the movie is as well—in science, you get small revelations, one at a time, rather than a huge, sudden reward.

KARPOVSKY: Right. So in terms of matching a tone to a setting, that was something we felt comfortable doing. Because you are working with co-workers in a group environment, but your work is often quite solitary. That creates a feeling of brooding, speculation, and meditation on the dynamics of the lab. It’s a lot of internalizing of feelings and emotions, which is something we wanted to play with as well. We wanted to have the slow, increasingly throbbing feeling that’s happening right below the surface, and exploring that with people who are wearing white lab coats.

SYMONDS: It seems like you guys could have a lot of fun with light, too, in that kind of sterile, creepy environment.

KARPOVSKY: It’s unsettling just being under those lights all day. It would drive me bonkers.

SYMONDS: This isn’t something that I think the film offers an answer to, but I’m curious: in a case like Paul’s, where someone develops an obsessive infatuation, do you think that was always going to be Paul’s destiny—it weren’t Danielle, it would have been someone else? Or do you think it was something specifically about Danielle that caused it to manifest itself?

KARPOVSKY: Interesting question. To back up for a second, Paul definitely has issues. He’s got childhood events that he’s negotiating with. Maybe the foundation of that experience would have ultimately supported an unraveling at some point in his life, based on unreciprocated desires.

What was different about his feelings for Danielle, who is a coworker in the lab that he has a really irrational obsession with, is the fact that he works with her. It’s one thing to have a one-night stand or a magical weekend with someone and then they go away and you’re still totally into that person. It’s one thing if a person goes away, and you don’t see them any more or they don’t return your emails or your phone calls, and slowly time passes and it heals the wounds. If you see that person every day, that wound is ripped open every day, and it might never heal. That’s what made Danielle different. They work in a small lab, there’s not that much turnover. You have to deal with this person every day. After months and months of that, you see her start flirting with a new co-worker, that’s going to destabilize you a lot. Especially for a guy like Paul, who has issues.

SYMONDS: Can you talk about the relationship with Paul’s sister? One interesting thing about his character is that he can do bad things and still be a good brother, a good uncle, a good worker.

KARPOVSKY: One thing we wanted to work into the movie, and we hope it does work in the movie, is we wanted to create Paul as a character who—yes, he commits a horrible act in the movie, but we still wanted you to nurture empathy for him subsequently. And still be engaged in his struggle. To do that, we have to create these relationships and dynamics before that that hopefully would build empathy for him. His sister was a crucial part of that—the fact that he spends time with her and tries to share his feelings with her often, even in a very compromised way, but at least he attempts to. She’s very caring as well, and she has a son, and he spends time with Paul. Part of that is to build up empathy with Paul, but more importantly, to see a very human and familial dimension to him—to see him without his lab coat on, and see how he functions outside of the work place where most of the film takes place.

SYMONDS: Could you talk a little bit about how the climax was framed? I think the trend in modern thrillers is to get the camera right up in there, rather than from a more objective wide angle, and a lot of directors today would have shot the scene in close-up. What made you decide not to?

KARPOVSKY: Because we wanted to make a film that was very subtle and character driven, from a visual sense, we didn’t want any close-ups because that would violate the subtlety of the movie and step into a conventional, familiar horror story that we wanted to avoid. One movie we thought did this pretty well and we were influenced by was Caché, by Michael Haneke. A lot of that movie is shot in wide shots, and a lot of the really horrific stuff that we experience in the movie is shot from a wide shot, and it doesn’t go in for gratuitous close-ups.

If you film a scene in a wide shot, especially a disturbing, distressing moment, I do feel like that helps you feel as though you’re the room with these people, instead of cutting it up and getting close—which you wouldn’t be doing if you were actually in a room with these people. What happens is people freeze, from a distance. That’s how we wanted to shoot the scene in the movie.

There’s a great scene in No Country for Old Men where Javier Bardem’s character strangles a police officer, and the Coen brothers use a lot of close-ups of shuffling feet. Though they did do a lot of close-ups, I think that was very powerful. Sometimes I think about that when I look at the scene in our movie—not at the same level, but the focus on the feet-scuffling was definitely present, at least, in both movies.

SYMONDS: I think it’s sort of classic, too, like Hitchcock: you know exactly what’s happening, but you’re not watching it happen.

KARPOVSKY: Exactly. Definitely Hitchcock, and in a weird way Basic Instinct, which I think is a very well-done modern noir that did a lot of these sort of things as well. We had sort of a symmetrical setup to the shot, which is kind of classical, in a sense too. We definitely wanted to have fun with that, to the extent that it didn’t feel like an homage—I think that would have been a sort of tongue-in-cheek, playful thing that would compromise the emotion of it. We wanted to do what we felt worked in these traditional, classical movies without feeling like we were giving a shout-out.

SYMONDS: I wanted to talk to you a little about directing yourself. I would imagine that you become really aware of the kinds of little tics in your behavior and how you look that most of us are able to be blissfully unaware of most of the time. How do you deal with that?

KARPOVSKY: I think you can get away with it if you don’t edit your own stuff. But I edit my own movies, too.

SYMONDS: So you’re screwed.

KARPOVSKY: Yeah, that’s when you really get familiar with the tics and mannerisms that normally you just don’t think about. Garth and I edited this movie together, and we were all too familiar with all the tics and stuff. There’s only so much you can do, physically. I really wanted to look different that I’ve looked in my other movies in the past. Just for the 10 people who have seen those movies and will see Rubberneck, I didn’t want there to be any association with a previous persona or image. I think just putting on a lab coat, glasses, slicking your hair a different way, does a lot, and then being in the kind of environment where scientists are actually working around you, which is how we shot it, during working hours, for the most part. We just kept very quiet, took a kind of lo-fi approach. A lot of the background chatter in the movie is real, which was tricky in the edit room because we would have to cut up sentences in the middle. But I hope that added a sense of authenticity to the story which we otherwise wouldn’t have had. I don’t think that really answered your question, though.

SYMONDS: When you’re the one in the shot, you can’t always know how it comes across. Does it get easier as you do it?

KARPOVSKY: It doesn’t get easier, but you can watch playback on these cameras very easily. We had such a small, mobile, and agile operation that if something didn’t work, we could redo it really quickly again. Having that option to immediately play it back took the pressure off and allowed us to immediately fix things immediately.

SYMONDS: So it’s not the same as Orson Welles putting himself in a movie.

KARPOVSKY: [laughs] Exactly. I don’t know if this is part of the question, but when I act in other people’s movies, I’m very curious to see how they direct and how they interact with their actors and their crew. That’s a way of learning and trying to get better, but there’s no way I could even remotely think about putting on my director’s hat while I’m acting in someone else’s movie, because that would totally dilute the focus of what they want from me. So I try to download and forget, download and forget.

SYMONDS: Is there anything specific from any of the directors you’ve worked with that you’ve picked up?

KARPOVSKY: Yeah, there are two. I’ve watched Lena Dunham do a few things now, Tiny Furniture and this HBO show Girls, which we premiered yesterday. I’m very proud of it. I think Lena Dunham did an incredible job. She’s an incredible writer; but the way she communicates with actors and expresses her ideas is totally engaging and fascinating. She’s trying to communicate a specific thought or joke or scenario in a way that is very coherent and you understand it very quickly, because we have to move quickly, but also in the way that kind of alley-oops you and allows you to finish it yourself and make it totally unique and singular within the confines of your character. She’s great at that. I think that’s one of her many skills.

And then the other directors that had an incredible influence on me, watching them work, was the Coen brothers. I shot a small part in their new movie, two weeks ago. Seeing the way they talk to the crew, their actors, and specifically to each other, was fascinating. That’s great, for any filmmaker, just to see them work is incredible, because they’re brothers, so it’s two directors, they’re both doing everything. But because they have to talk to each other, you can actually see inside the mind of the director, which normally doesn’t happen. That was incredibly fun and rewarding.

RUBBERNECK PREMIERES AT THE TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL TONIGHT AT 6 PM AT CHELSEA CLEARVIEW CINEMAS, AND ALSO PLAYS MONDAY, APRIL 23 AT 9 PM AND SATURDAY, APRIL 28 AT 2:30 PM. FOR MORE ON THE FILM, VISIT ITS WEBSITE.