Albert Brooks Enjoys the Ride

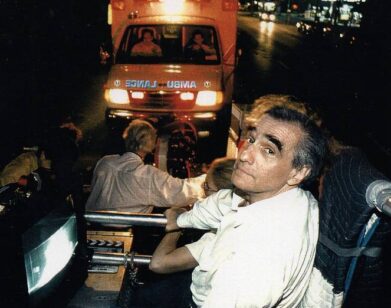

ABOVE: ALBERT BROOKS IN DRIVE. IMAGE COURTESY OF FILMDISTRICT

Let’s not call it a comeback, because Albert Brooks never really left us. Let’s say he’s finally getting some well-deserved recognition as one of the most brilliant talents, comedic and otherwise, in the last four decades. On the back of his critically acclaimed novel 2030: The Real Story of What Happens to America, he surprised audiences in Drive with a dramatic turn as Bernie Rose, the quietly threatening West Coast mobster who’s fond of Tommy Bahama shirts and commits random acts of violence. The role is one of the most talked-about this year, a sure bet coming down the stretch of awards season—already, Brooks has garnered a nomination from the Independent Spirit Awards and a ton of Oscar buzz, and last week, he picked up a Best Supporting Actor award from the New York Film Critics Circle.

Interview spoke with Brooks over the phone about the film and the bizarre life it has taken outside the theater, and told us about a new word he coined.

CRAIG HUBERT: I figured we would get this out of the way quickly. What’s going on with this lawsuit concerning Drive?

ALBERT BROOKS: All I know is what I’ve read. I think it’s one of the great silly things of all time. I’m honored to be involved in a lawsuit like this. I don’t know where this started, and I really think it’s for publicity’s sake. I can’t imagine this is real.

HUBERT: The lawyer for the case has been arguing with people in the comments sections of blogs. And there is also this guy who threw the hot dog at Tiger Woods, who claimed he was inspired by the film. Did you ever expect this film would take on such a life of its own outside the theater?

BROOKS: [laughs] You mean did I ever expect that I would ever be in a movie that would result in someone throwing a hot dog at Tiger Woods? Never in a million years.

HUBERT: It must be great.

BROOKS: I never knew Tiger Woods would be part of this movie.

HUBERT: Have you had any strange experience with fans?

BROOKS: Well, no, but I’ve been involved with movies with strange experiences. I was in Taxi Driver, and remember, Taxi Driver was John Hinckley, who tried to assassinate Reagan. It doesn’t get weirder than that. If I really stop and think, I’ve been in enough movies, there’s been some pretty odd behavior here and there. That one really stands out.

HUBERT: What was the first thing attracted you to Drive?

BROOKS: Well, it was playing a different character than I’ve played before, that was first and foremost. I was looking to do that. Also, I was familiar with Nicolas Refn; I had seen Bronson and thought it was terrific. Ryan Gosling was attached. So you get enough things that draw you in—because sometimes you get sent a script, and the people attached you don’t respect. It all sort of has to gel. But first and foremost, the part was something I thought I could do and was different than I had played before.

HUBERT: You said you were familiar with the director’s work—and Nicolas Refn is such a visual stylist. Is that something you look for, as a filmmaker yourself?

BROOKS: You look for somebody that has—I wouldn’t necessarily say you need to look for a visual stylist. They have to have their own niche, even if they’re just starting. They have to have something, because it’s such a director’s medium. Once you sign on as an actor, you know, you don’t go to the editing room, you don’t see how they cut, you don’t see how they score, you don’t see how they cast the rest of the movie. You got to hang your hat on something. Now, you can work for a first-time director and get a feeling after you meet them, and think this person is going to be something. So you’ll hang your hat on a feeling. With Nicolas, he had shown what he did. What he did was distinctive that you say, “I’ll play on your team for this. Good luck!” [laughs]

HUBERT: As a director, is there ever the sense you want to work with a director—Nicolas, for example—just to watch them make movies?

BROOKS: You do, you’re there, you have to observe. I probably learned, being in Taxi Driver before I made my first film, I would come to the set every day just to watch how that film came about. It’s like a graduate course, it’s terrific. You talk to the cinematographer during the breaks. You ask the electrician why they are doing this. But, you know, I know enough how films are made that I’m not going to bug the electrician. When you’re in a film, you are watching, you’re observing, you’re even chiming in. It was great; I liked watching Nicolas work.

HUBERT: How of much of Bernie Rose was in the initial script, and how much was built during discussions later on?

BROOKS: I don’t remember, exactly. Obviously, the character was there, because it came from the novel. What we did is, as soon as he cast it—I think I came on after Ryan, and Bryan Cranston, then I think Carey Mulligan came on, and then I think Ron Perlman came on. Once Ron Perlman was cast, we would rehearse for several weeks at Nicolas’s house. I think that sort of developed a relationship, how Bernie would react to Nino. Once the cast was in place, the writer was there and we sort of did improv, and rehearsed, tried to develop—for example, the ways in which these murders took place were not specific. They had to be thought out. It didn’t just say, “Slits his arm.” It had to be figured out. Certainly the frame work was there, in a very good way.

HUBERT: Some of the specifics of your character, especially the external things like the shaving of the eyebrows, the shirts he wears…

BROOKS: Yeah, that’s my job. I found a hairpiece—Nicolas went back to Denmark—and I knew what I wanted the character to look like. I had make-up people that I work with on my movies, and I went to work. I emailed him photos, and I would wait with baited breath, and he would write back, “Terrific!” [laughs] That’s my job. Sometimes a director will have it down to that, but mostly when you hire an actor, you want the actor to come at you with these thoughts, because the actor’s going to be the one who has to actually say the words and play it. I knew how I wanted Bernie to look. There’s a style in which you walk, and look, and what kind of jewelry you wear.

HUBERT: One of the most interesting things about Bernie is that, even though he does bad things, he never seems very angry—or as angry as his counterpart, Nino. He reacts when his hand is forced.

BROOKS: That’s exactly like, because Nino is all show. Bernie doesn’t do that, he’s tired of it. It’s just not his style. I think if Bernie wasn’t crossed in the way he was, I don’t think he would be doing any violence. He’s past that. He’s not getting up in the morning anymore looking for a fight. He had his fights. This whole thing is dumped in his lap, but he’s still going to react. If it’s him or you, he’s going to pick himself.

HUBERT: The way Bernie gets angry in the early scene, eating the Chinese food, reminded me of the character you play in Lost in America, the way he explodes on his bosses when he is pushed.

BROOKS: Even in my comedies, I don’t take anger as a joke. I think anger and laughter are very close to each other, when you think about it. One of the things I like about a character: I always think it’s fascinating when a character can turn on a dime and go from one emotion to another. I like watching that.

HUBERT: The film has been released for a few months now, and your name is bounced around with the all the awards chatter. Is this something to which you pay attention? Does it make much difference to you anymore?

BROOKS: You’d be an idiot not to enjoy hearing it, because it only means that people are enjoying the performance, but there’s nothing really to do—it’s sort of a betting game, and I guess it’s fun to have a chip on the table, but I can’t really do anything about it. All it means is—you know, I’ve been in a lot of movies where they didn’t make it into the discussion. Would you rather have the discussion or no discussion? It only means the movie kicked some ass.

HUBERT: I know you had a fairly successful book— [pause] I’m sorry, that makes it sound really bad. I actually really love the book. I was trying to pay you a compliment, and it sounded like an insult.

BROOKS: I have a word for that, you know. I coined a word for that: “complinsult.” [laughs]

DRIVE AND ALBERT BROOKS’ NOVEL 2030 ARE BOTH OUT NOW.