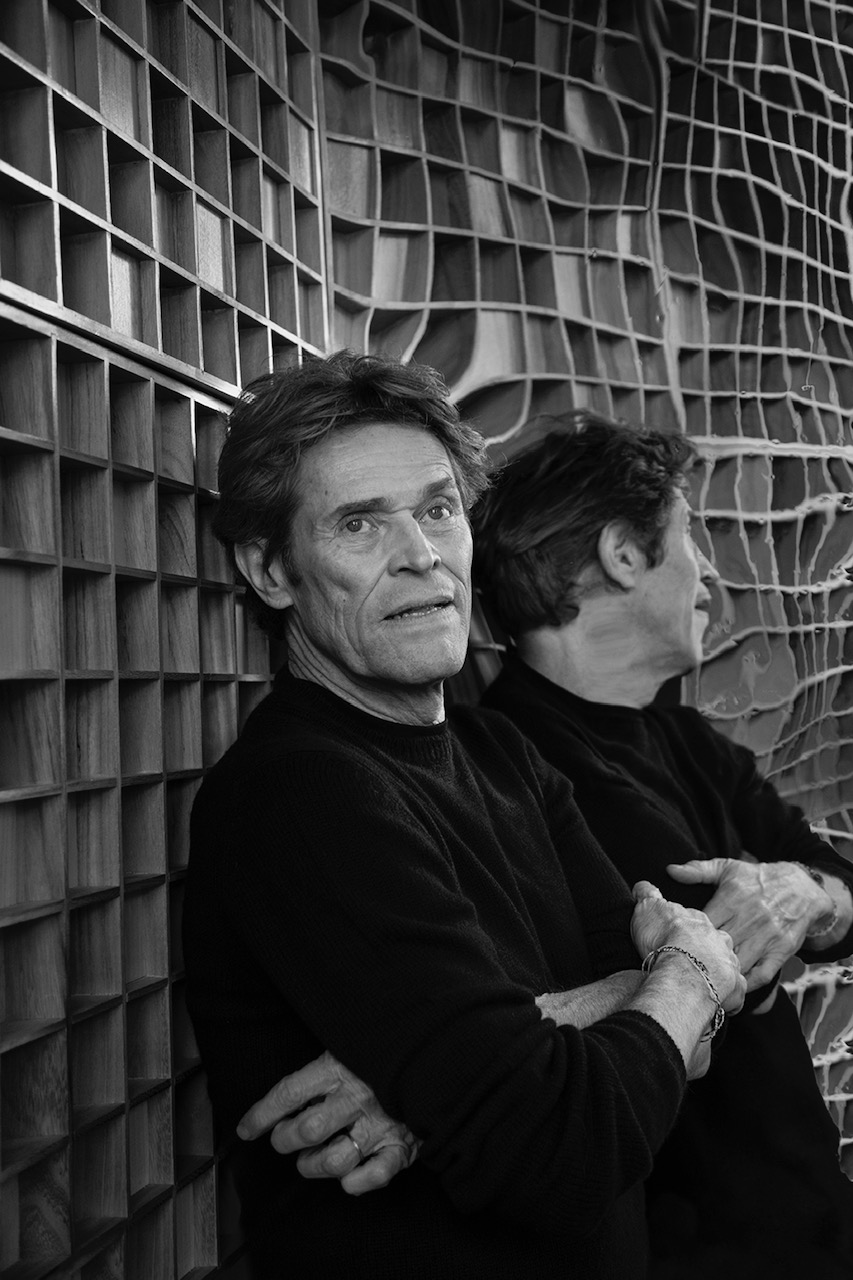

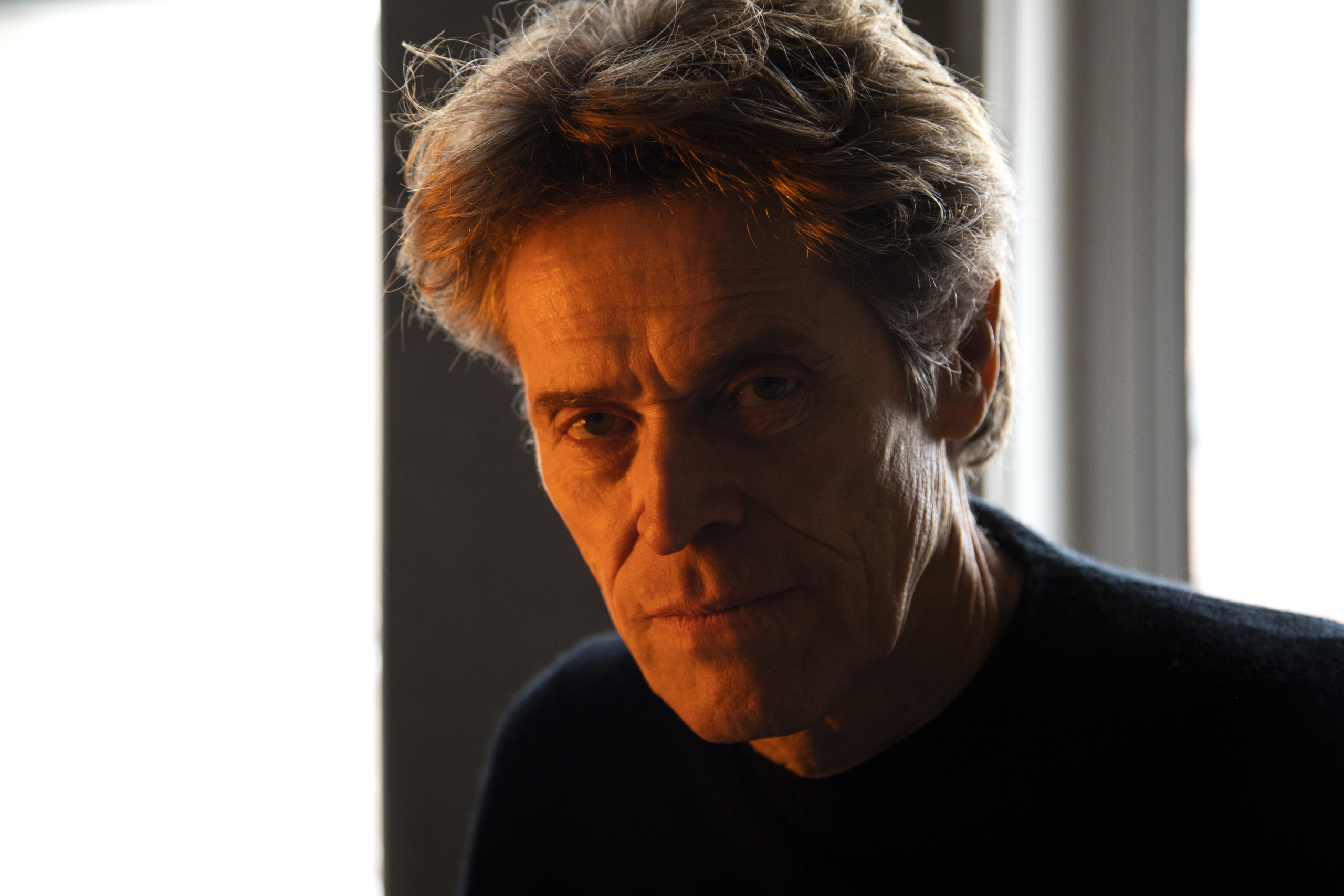

Willem Dafoe and Abel Ferrara Just Can’t Quit Each Other

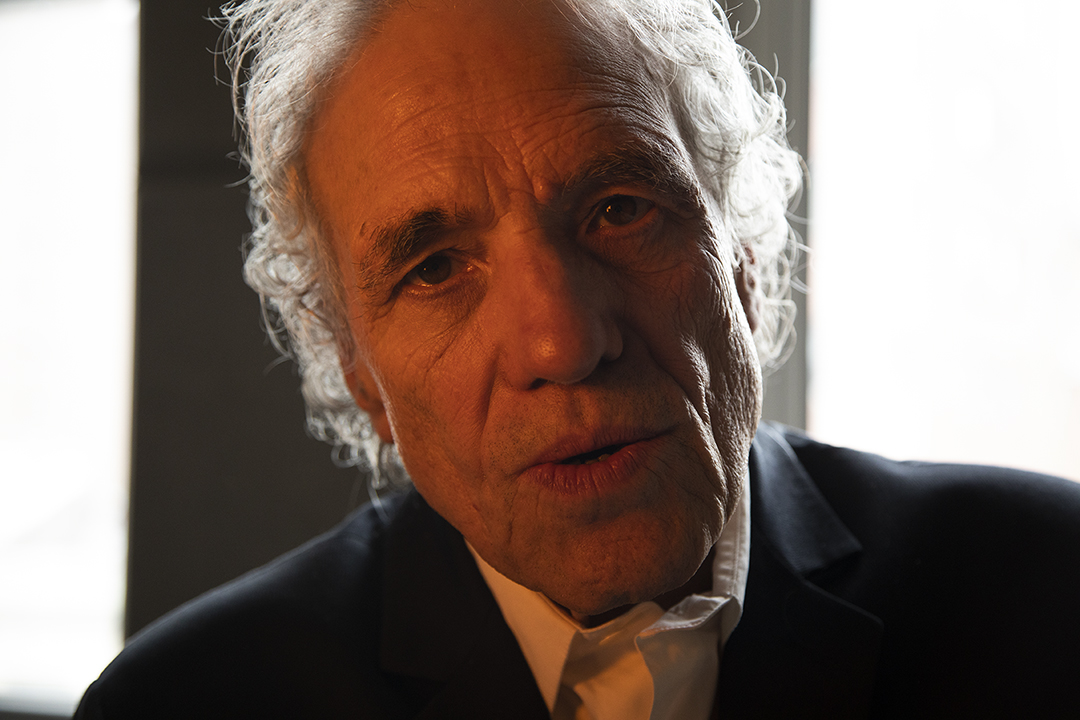

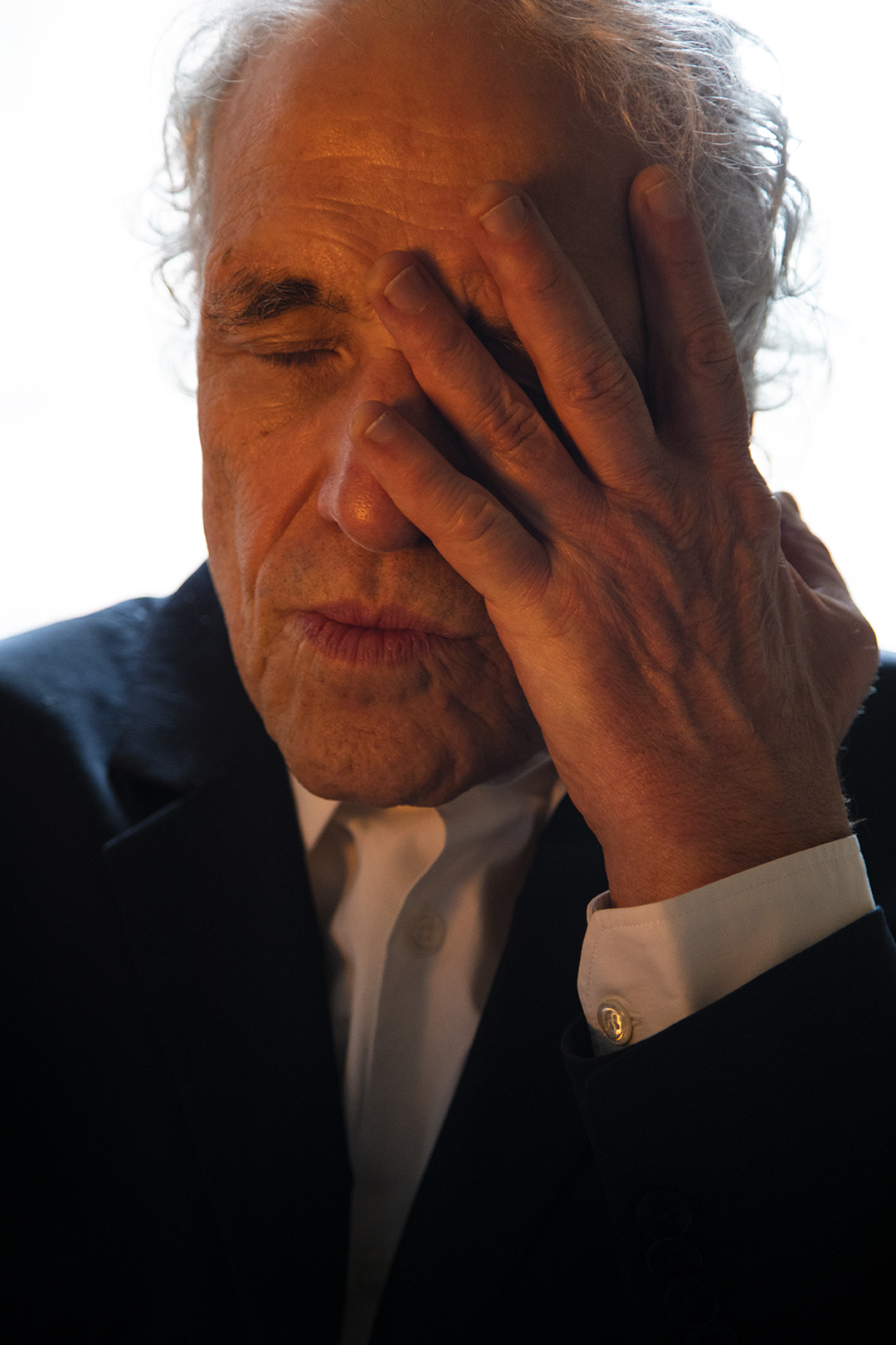

When Abel Ferrara says that sometimes, he has an idea so wild that even he doesn’t want to see it through, you believe him. Those familiar with Abel and his work can place the director in the Scorsese and Coppola family—a sort of twisted cousin who you’d think twice about before inviting to a family dinner. Like those directors, Ferrara cut his teeth creating gritty, thrilling stories of the city before the better days of its economy. His most famous films, King of New York and Bad Lieutenant, which centers on a coked-up cop, portray a New York that was ruled by money, not law, and unbothered to even pretend it was the other way around. In the wake of the recent Black Lives Matter protests and our nation’s reckoning with police brutality, these films start to seem less and less archival.

Ferrara’s particular forays into power and corruption are distinct from his peers in that they embrace exploitation and dancing with our most reprehensible impulses. It makes sense that Willem Dafoe, who has gone on record about his enthusiasm for submitting to primal instinct, is Ferrara’s soulmate in experiment. Tommaso, a portrait of an American director in Rome trying to outrun his creeping, dark ideas, will be their fifth film together, with Dafoe acting as husband to Ferrara’s actual wife and father to their actual child; the film is currently streaming via Kino Lorber. The upcoming Siberia—about which Willem only says that there are bears, stunts, and “dream stuff” (oh my)—will be the pair’s sixth collaboration. We got on the phone with Abel and Willem, who engaged in a rambling conversation about guerrilla filmmaking, leaving New York, and, after all these years, still being full of surprises. —BESSIE RUBINSTEIN

–––

ABEL FERRARA: Usually people ask about the character of Tommaso and me—if he’s me.

WILLEM DAFOE: Listen, I don’t think in terms of character, and I don’t think in terms of autobiography. We made this film in a guerrilla-style way. You had some ideas. Some of it was more developed than others. Some was just 100 percent set up and then improvised. We’re just dealing with some things that we know and things that are around us. People think we’re trying to head-shrink you, or we’re trying to explain away your life, or that you’re using this film like psychotherapy. It’s a really important distinction that that’s not what’s going on. We’re expressing what our experience of our lives are, but not necessarily in a direct way. I’m the godfather to your child. We both are Americans who live in Rome. We have a lot of similar struggles and a lot of similar interests, so that brings us together. You’re a self-starter. We both like to do what we like to do. We always try to find situations where we can exercise that and find something out. That’s the pleasure you have when someone lets you participate in a way that’s fluid. This was very fluid. I’ll kick off with that, otherwise I’ll talk forever. I’m wound up.

FERRARA: I think we’ve been doing it like this the whole time. I made Dangerous Game—my wife [Nancy Ferrara] was in it and played against that that kind of relationship. We film what’s in front of us. What’s in front of us is basically our modus operandi—the elements that are there and, really, where the creative drive comes from. Where the essential idea of a movie comes from…I really don’t know where that does come from, but it’s almost always just the beginning of it. That’s just a starting place. Sure, there were scenes I could have imagined. There was a bit of a script. But certain scenes were made up.

DAFOE: Particularly, the flashbacks. You would take me aside and tell me a story about something that you wanted to see, and then we’d try to find our way to that. Sometimes we would and sometimes we wouldn’t. But the really interesting thing about working in this loose way was that it was about the quality of being there and the reality of being engaged. We didn’t have something to prove. We didn’t have something that had to be accomplished in the scene. It was seeing where the scene would take us. It’s nice when you have an authority in your pretending. You come up against it and you learn something. That’s what going to the cinema is great about. It can extend your experience. I can know what it’s like to live as a drag queen in Harlem, maybe. I will never be that, probably.

FERRARA: You never know.

DAFOE: But I can be there with the life of a drag queen in Harlem and consider, not only that life, but also my life in a different way. I think that’s the goose that you get out of doing this kind of work.

FERRARA: The idea of Tommaso, being who he is and what he is, he could have been an actor as well as a director. He has his own life and he has ideas for films that could be or could not be. The passion, for whatever reason, is part of Tommaso, whether he actually played the role on the cross, like you had with Marty [Scorsese], or he is thinking of a film he wants to make. Maybe he’s just daydreaming of a film he doesn’t even care to make. A lot of times, I just run a fucking idea by my head and I’m thinking, “Wow, that’s cool. I don’t even want to go there in terms of making it.” The Pontius Pilate, the idea of him out in the thing—we actually threw the idea up. Remember, Willem, I said, “Let me see if I could ask Marty just for those scenes,” because in the scene he really takes his heart out. There’s a beautiful scene in The Last Temptation—I wanted you on a cross to be in this film. Why exactly didn’t you want that?

DAFOE: I just thought you were pointing outside of the reality of the film. The best thing was that we were making something that was contained, fluid, and very personal. Then you’d invite polemic meaning-things that I wasn’t down with. Talk about submitting to a director! I give into you because you need it. For example, the scene where we’re crucified outside Termini, that did appeal to me, just almost from a performance-art standpoint. How interesting is that to go to Termini Station, put some guys up, abstractly, in crucifixion poses and film people’s reactions to them? That’s interesting. So I’d say, “Okay, I don’t know what it means, Abel, but if you need it, we’ll do that.” I don’t know what it means, but I don’t have to know what it means to play it or to be there. In fact, being there is figuring out what it means. You’re just trying to survive.

FERRARA: The process of filmmaking is what gets us to the end. People say, “What did you think of that? What made you decide?” I don’t even try to go there. If I start thinking like that, I stop myself because I just have the instincts and feelings. If I’m in the right place with the right people, I believe in the cinema. I believe in the process. I know we’re going to get someplace. There’s the editing, too. So, if, a lot of times, we don’t get somewhere, that’s fine too. We could fail. They’re not going to put us up on a cross because we took a shot on a scene that didn’t go anywhere. Talk about survival—Tommaso knows that these demons in him that made him do the things he did don’t disappear. They’re there. Now, how do you deal with that? You can drink and drug, and do this and that, or you could practice, you could go to the meetings, you try. It’s the trying and the moment-to-moment of the trying. Tommaso has not been reawakened during this process. Willem, talk more about that.

DAFOE: Well, no. Let’s move on to something else. I can’t follow up on that.

FERRARA: Okay, fine. You’re full of surprises.

DAFOE: Do I still surprise you? I hope so. We have fun. This gets more and more fun.

FERRARA: You’re one big, infinite bag of surprises. As we move forward, we’re all changing, we’re all doing things. Willem, you work all over the world. Now, we’ve all been in the grip of this virus, but, still, you’re doing a lot of changing within the walls of your house, and so am I. It’s a great mystery, what we do, making movies. We’ve got a deep belief of how important it is. If that camera wasn’t on that guy kneeling on George Floyd‘s neck … that’s the most important shot you’ve seen forever. It just shows how important the process is, the power of image. The power of the need to film to express ourselves to each other. It becomes more important every minute, for me.

DAFOE: Does what’s going on in New York surprise you?

FERRARA: It is what it is. This is the scene it’s making. I left New York because I couldn’t take it—every block, every street is a temple to something. Whether it’s Nike or Apple, or cities that have churches, synagogues, fucking mosques. Even statues of somebody or other people. When you’ve got the perfect storm of a virus where everybody’s locked up, 40 million people are out of work, you realize that the government doesn’t exist. If these guys can’t come up with masks and gloves for the fucking doctors after three months. Plus, this guy in the White House, it’s a karma of every word out of his mouth, every action he’s doing. These kids come out wilding like this. It’s lack of spirituality. I see myself in them, I see myself in the cops, I even see myself in fucking Trump sometimes. It’s going to spin out of control and it’s about fucking wanting this because that’s how we feel. We’re all being pushed. We want it. Willem, it’s your last speech in Pasolini.

DAFOE: The problems have always been there and various situations have made it explode. It was bound to happen. But let other people talk about that. You like to talk about it more than I do. I got plenty to say about it, but I feel more knowledgeable about talking about something that I know, like Tommaso. I don’t want to be some actor that, because he’s doing an interview… Some people do it very well. It’s the old story. I feel like I can express myself by what I do and that’s when I’m most articulate. When I try to contribute in another way, it clouds things. I don’t feel clear.

FERRARA: Yeah. Let’s talk about Siberia.

DAFOE: I remember you had some ideas that we weren’t going to put those up on the screen, but they were what was driving the soul of the thing. You knew what you wanted to see. Unlike Tommaso, it wasn’t like stuff that is around us. It was stuff that we don’t really know. It was fantasy stuff, it was movie stuff, it was dream stuff. Because of that, we couldn’t shoot it in a shoot-from-the-hip guerrilla style. There’s stunts in it, there’s bears, there’s different kinds of things that we didn’t want to do on the fly, because it was about a cinematic language for some stuff that can’t quite be expressed any other way. Internal stuff. Tommaso is kind of a child of Siberia. Is that fair?

FERRARA: Sure. That’s a good way to put it. Siberia has everything to do with Tommaso. He’s writing Siberia. Those are his storyboards.

DAFOE: But that’s not even that idea. It’s more that that stuff is on the desk in your room, so, when we’re making the scene, that’s part of the mise-en-scène. That’s part of the landscape and we deal with it. We aren’t dropping these connecting things to link it. It’s what’s in the room. It’s like, deal with what’s there and see where it takes you. That’s how Tommaso was built. Siberia was a little different because of the exotic nature of shooting in forest, in full desert and really brutal snowy mountains. Filming with dogs, with a lot of exotic characters. That needed a different approach, but it comes from the same pool of concerns in the same head.

FERRARA: Right, because we came up with this from the same period. And we’re prisoners of our imagination. We have certain ideas come, then that’s what we’re going to have to confront and deal with in whatever way. Then we take it from there. It’s a matter, again, of belief in the process and the people who are helping us make the film. It’s a troupe.

DAFOE: I remember at one point when we were talking about Siberia and we didn’t have the money to do it yet, basically I said, “Abel, let’s just shoot it in your apartment.”

FERRARA: It was a good idea. [Laughs] In the end it might have been different.

DAFOE: I was like, “Give up on these grand images. We’ll find equivalence. We’ll be forced by necessity to figure out a different way to deal with these impulses.” Now, thank god that never happened.

All I think about is being clear and calm. That’s what I try to do. That’s my work, to be clear and calm, so when I have to do things, I do them in an awake kind of way. As a performer, it’s so much about walking that tight rope between control and abandon. The abandon part is the easy part. The other part is harder—having the control without having it be repression, but having it come out of clarity, out of the quality of being present in everything that you’re doing. When I was younger I probably thought it was pretty good being insane. Just wild. People think, “Wow, if you get chilled, then where do you burn hot?” The truth is, if you get chill, then you can burn hot when you want. That’s much better.

FERRARA: That was beautiful.

DAFOE: These are hard to do. Now you know why I work with you, because I can struggle to figure something out, with sincerity. Sometimes we bullshit, but you can take it to another level. That’s a good collaboration. You encourage me to stick my neck out a little bit.

FERRARA: We need to encourage everybody else to go see these movies. Tommaso and Siberia—a double bill.

DAFOE: One thing that just occurred to me—right now, this film is going to be released in a hundred theaters, virtually. I’m not down with the streaming stuff so much, but you realize that it may actually be more widely seen this way?

FERRARA: Yeah. [Laughs] Hey, I’ll meet you on the White House lawn, 4th of July. Okay? Be there.