Abel Ferrara’s Teacher

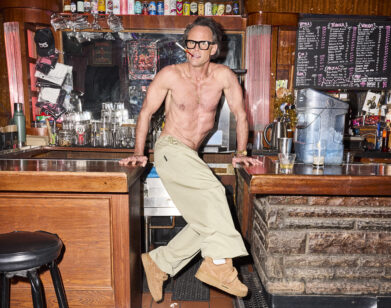

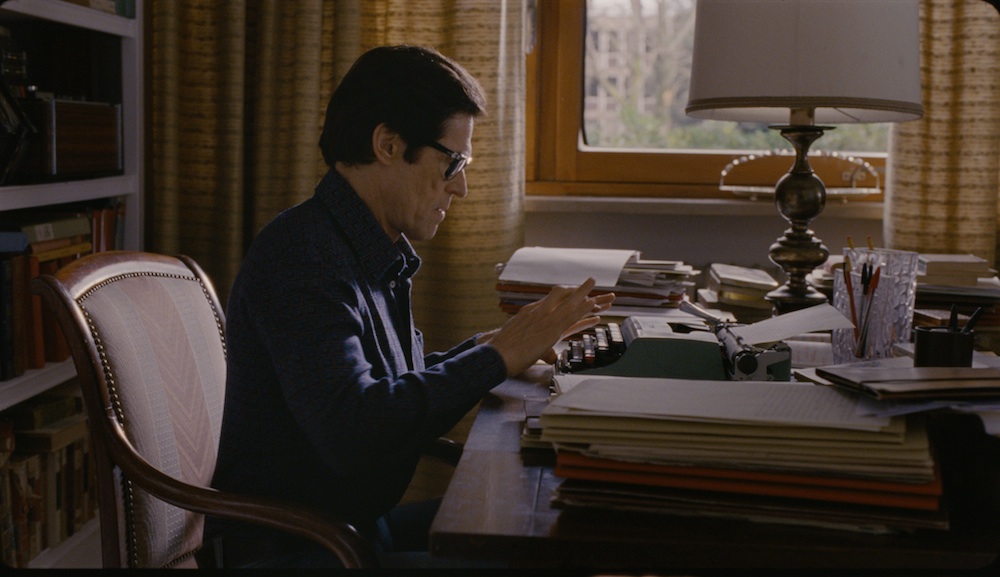

ABOVE: WILLEM DAFOE IN PASOLINI

Abel Ferrara is no stranger to this magazine. Just last year we published an interview in which contemporary artist Aïda Ruilova spoke to the famed director about Pasolini in its nascent stages. Now the passion project he’s been mulling over for years has come to fruition. And it’s brilliant.

At 66, Ferrara injects Pasolini with the same intensity and vivacity that we’ve relished in for upwards of four decades. Although less violent and sadistic than King of New York (1990) or Bad Lieutenant (1992), Pasolini is very much a Ferrara endeavor. Uncompromising in its vision, the movie explores the final days of polemical Italian filmmaker Pier Pablo Pasolini. The film is a sumptuous subversion of the modern biopic—uninterested in a remedial examination of this man’s life. There are no flashbacks, no summarizing montages, and no chapter cards to signify time. In fact, one must look no further than the unusually short 86-minute runtime to know this isn’t your standard hagiographic biography. As actor Willem Dafoe, who masterfully assumes the role of Pasolini, noted, the movie is more “impressionistic” than anything else.

A kaleidoscopic exploration of a perplexing human being, Pasolini ebbs and flows with the candidness and confidence that Abel Ferrara exudes in person. In our discussion at the Toronto International Film Festival, the Bronx-born and raised auteur opened up about his sobriety, Buddhism, the press, film preservation, and how Pasolini influenced his career.

SAM FRAGOSO: You’ve become pretty notorious for your interviews.

ABEL FERRARA: [laughs] Depends on the interview. Depends on the questions.

FRAGOSO: I’ve been thinking about the idea that people accumulate knowledge over the years. Do you believe that?

FERRARA: What I like about that is that [Pasolini’s] talking about a 1,700-page book he had just written, and that quote comes from him talking to his friend Alberto Moravia, a great, brilliant writer—the guy who wrote The Conformist, a great novel. And he’s basically saying, “Hey, this 1,700 pages just got me to here, so I’m not interested in these 1,700 pages. This is a preamble to what I’m going to go to.” So he’s a cat who is always there with the future. Those 1,700 pages, who knows if he’d even release that? Maybe that was just his way of getting to the point of going to the next idea of the next fact. His accumulation of knowledge led him to what? That things aren’t what they seem.

FRAGOSO: Have you found that to be true in your own life? That at the end of the day—and your films—you’re a bit wiser?

FERRARA: I feel like you’re constantly changing. The world is constantly changing. You’re constantly learning and you have to be willing to get off your mark, and get off your spot and take that knowledge you have not to fix yourself into a place but to keep going. That’s what I learned the most out of this film. With [Pasolini], he was always on to the next film, to the new wave. Salò was a fucking modern… he was reinventing the form. That’s a great tragedy because he was really at a strong place. But he was always there. A guy like him was never going to get distracted.

FRAGOSO: To me it seems even if a film was a misfire, or his vision didn’t exactly come to fruition, he seemed unaffected. Bettering himself and his craft for the next project. Have you adopted this philosophy?

FERRARA: You can’t get hung up on that. They were a process to the next film. I mean, hey man, a lifetime isn’t long enough to learn how to make films. What did Kubrick say? “A film needs more than you can give it in a lifetime.” With these two things in mind you just gotta constantly follow your imagination. Listen, I’m a slave to my imagination in terms of making narrative films. But [Pasolini] is saying narrative art is dead, so we make documentaries and find out they’re more narrative than fiction.

FRAGOSO: Do you think narrative art is dead?

FERRARA: I’m rediscovering how to tell a story in every way.

FRAGOSO: That’s exciting.

FERRARA: Well if it’s not exciting then I can’t do it. It’s exciting and I’m exciting. The adventure is still there for me.

FRAGOSO: Pasolini’s perspective is such a somber one. You don’t believe everything in contemporary cinema is shit, right?

FERRARA: No, not at all. I hope not. I mean for your sake. These guys are out there. They’re trying. They’re going for it. There’s a certain period in your life where you’re a spectator of films. For me it was 1969 to 1974. Thank God it was a very, very powerful period in the history of cinema. The same thing for music. My period as a young teenager when you really listen to music so you can get understand a little bit more about what the music is was, say, 1965 to 1968. I was just lucky to be in those times.

FRAGOSO: How much as changed since you started making films?

FERRARA: Everything has changed, but the process of telling a story has not changed. It’s like cavemen sitting around the fire; somebody’s going to tell the story. Somebody is drawing on the wall. You’re communicating. You’re trying to learn and teach at the same time. You’re your own student and you’re your own teacher, but the process is of the communicating.

FRAGOSO: And has your need to communicate through film ever faltered?

FERRARA: Everybody has their black moments. No, because that’s my training. It’s not even a gift, it’s a desire. Getting back to Pasolini, when [I] really got to know him and got to talk to the people who really knew him, it was not so much as passion—which was incredible—it was his compassion. This guy believed in people and dug people and loved life and loved the interaction there.

FRAGOSO: I’m always fascinated in the fine line between passion and obsession. It’s not that you want to make films, it’s that you have to.

FERRARA: It’s the reason why you’re doing it. It’s a passion when you’re doing it for other people and you’re doing it for the people around you making the film and the people who are going to see the film, and the giving. When you start thinking about you doing it for some sort of self-gain, then I think it becomes an obsession. It becomes a negative experience.

FRAGOSO: And you’ve had those.

FERRARA: Yeah, big time, man. I lived, but for me it was a different thing because I was an addict. Well, I’m still an addict but I used and abused drugs and alcohol. When I stopped doing that it became a lot clearer that life goes from inside to giving as opposed to taking and destroying.

FRAGOSO: Are you glad you can give now?

FERRARA: I’m glad I’m clean, yeah. Big time.

FRAGOSO: No nostalgia for the past?

FERRARA: Nostalgia? No. I don’t have regret either.

FRAGOSO: Is that because you simply learn from your mistakes?

FERRARA: Exactly, and regret isn’t going to get me anywhere. It’s like being obsessed with something. It doesn’t bring you anywhere. You’re changing and you’re learning every year. And today is today, you know what I mean? And we have today and we have the future.

FRAGOSO: Do you remember your 20s?

FERRARA: Yeah. Shit yeah. I remember big time.

FRAGOSO: What was it like?

FERRARA: My childhood was great. Teenage years were really cool. It was like Woodstock. It was that period of creativity. We were expected to be creative. We expected to do these things. I came from a loving family and a supportive family and supportive friends and we were doing our thing.

FRAGOSO: Are we expected to be less creative as we grow older?

FERRARA: We can’t. It absolutely cannot.

FRAGOSO: But you see this all the time. People who are passionate about making something in their 20s and then slowly—or quickly—slide into this banal 9-to-5 routine.

FERRARA: So maybe that was really what they were meant to do. I don’t know man—to each individual’s own. Some people maybe try to a certain point and then realize it was not what they were meant to be.

FRAGOSO: You’ve gone through a lot, though, and I think it takes a certain kind of person to endure all that nonsense.

FERRARA: It’s what I do. It’s as simple as that. Whether it’s a gift or it’s an accomplishment, it’s what I do. Somebody’s the director of the group, of the film. Willem is the actor and I’m the director. We each have our special gift and that’s mine. And I’m cool with it, and I’m more cool with it the older I get. I’m trying to keep it real and make it real for the people who are going to watch the movie, and make them get it. You know we got some nasty reviews and they were like telling me, “Oh, they didn’t get it.” Yeah, but it’s my job to make them get it, you dig? It’s not my job to beat them over the head because they didn’t understand the film.

FRAGOSO: But there are people who don’t like Citizen Kane—there will always be someone who finds a reason to not like something.

FERRARA: Right. When they say it I just tell them, “Watch it again five years from now and see what you think.” Don’t get carried away. Don’t get obsessed with not liking a movie. It’s funny when we’re doing these Q&As and somebody says, “I hate the movie.” Then why are you still here, dude? You get the satisfaction of telling me my movie sucks?

FRAGOSO: That seems a bit masochistic.

FERRARA: You either connect or you don’t connect. It’s not the end of the world, man. It’s a movie, you dig? Do you know how many films I couldn’t understand? Couldn’t see? Could not even sit through? I watch them years later and it’s like a revelation.

FRAGOSO: Different stages of our lives changes how we experience art.

FERRARA: Because you’re constantly changing man. But the film’s not changing. The film stays the same. That’s the beautiful aspect of it.

FRAGOSO: And then you interact with that film.

FERRARA: Yeah you interact what that film, but does the film really change? If you’re viewing it in a different way then the film’s not the same, right?

FRAGOSO: To you.

FERRARA: Well where is the film? Is the film in the screen or in your heart?

FRAGOSO: Do you have uncertainties about the future of film and its preservation?

FERRARA: Well, Pasolini was shot on negative. I was kind of realizing that I was in the generation of directors that went from film to digital just because I was told to. Because I didn’t put up a fight. I didn’t want to say, “Hey man, I don’t believe it.” You don’t know what the digital experience really is, or if that file is going to last or not? Or if somebody is going to come up with a hack or a fucking light storm on the sun and every fucking digital computation is gone in the whole world. There’s a movie right there. Every fucking photograph in your phone, every fucking bit on your computer, the whole world could come back to 000. The only thing that’s there is a Polaroid from 1978, or a film shot on negative. Hopefully the film is preserved in your mind.

FRAGOSO: Is Hollywood cinema “the devil,” as your film proclaims?

FERRARA: Well, no, it just sounded like a good line because Laura Betti did the voice of The Exorcist. I love that line when he says, “Give an old altar boy a break.” That’s when the priest is getting a subway and he’s all alone in the subway, and there’s a bum lying there saying, “Can you give an old altar boy a break, father?” Later, the chick is in the bed and he’s trying to figure out what the fuck is going on. And that chick in the exact voice is saying, “Can you give an old altar boy a break, father?” Then he knew. It was a very chilling moment in that film, if you believe in the devil. Which I no longer believe. I’m a Buddhist now so that shit doesn’t scare me like it did.

FRAGOSO: When did that happen? When you became sober?

FERRARA: Yeah, I was a Buddhist for about eight years. You can’t be a Buddhist if you’re using. It’s impossible.

FRAGOSO: Are you glad you became a Buddhist?

FERRARA: For me it locked into my teachings of Jesus and it makes sense to me. It’s a philosophy of life, like making the movies, working on the films, on the compassion, on why I made Pasolini and who he is to me and what I learned from it. It’s a Buddhist deal. You meditate on your teacher, and he was our teacher. Why do we like him? Why did we want to make that film? What is the reason? That’s what this film is for us.

PASOLINI IS CURRENTLY SCREENING AT THE TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL.