NYFF

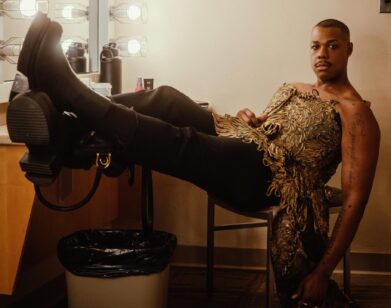

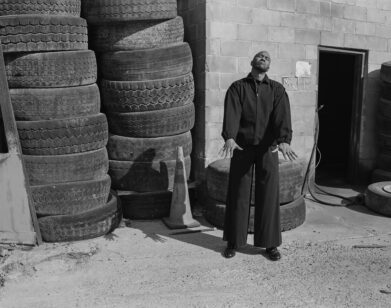

“You Can’t Put Me in Any Box”: 30 Minutes With Filmmaker Mati Diop

MONDAY 3:40 PM SEPTEMBER 30, 2024 PARK LANE HOTEL

In 2019, Mati Diop’s debut feature Atlantics made history as the first film directed by a Black woman to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival. It’s a hard act to follow, she confesses, but the French-Senegalese filmmaker has done something even bolder with her sophomore effort Dahomey, an experimental documentary that dramatizes the return of 26 royal treasures from the Kingdom of Dahomey from a museum in France to the Republic of Benin. The film builds not only on the director’s exploration of Afro-disaporic stories, but also on her uniquely inventive cinematic language. “When it comes to my art—my language, what I should defend, what I should stand for—I have no fear,” Diop told Jeremy O. Harris when the two sat down earlier this week before the film’s New York Film Festival premiere.

———

JEREMY O. HARRIS: I love that we’re both wearing Crocs today.

MATI DIOP: [Laughs] I know. I mean, what else?

HARRIS: How’s it going being in New York again?

DIOP: It’s super. I haven’t come back here since Atlantics, so five years ago. It’s good to see you again, by the way.

HARRIS: Likewise.

DIOP: It’s really great to be back because New York is a very special city to me. I don’t think I would be making movies without a certain cinematic scene from New York. It’s a city that has produced and given me a lot as a teenager. And I guess films by John Casavettes, Harmony Korine, especially the work of Nan Goldin, they all completely got me into it when I was around 17 or 18. It’s also the first city where I traveled on my own. I always felt much more heard and understood than in France. I feel that my work has a reception here that’s so much more vast.

HARRIS: What do you think that’s about?

DIOP: It instantly takes me think of music of the West Indies, to the transformations that African music underwent through the transatlantic slave trade. When I think of a Brazilian audience watching Atlantics, I imagine they’re having a way more layered experience than a French person due to such a strong Afro-diasporic resonance.

HARRIS: Totally. And from a colonial lens, there’s probably a sort of wall up to certain ideas that you’re proposing.

DIOP: Exactly. As a black woman artist, I often felt that I was perceived at only 20% of all my dimensions. At the time of my film Atlantics, I felt that French people and the French press got very overwhelmed with my profile. Like, “Okay, she’s French, but she shoots in Senegal, in wolof. Her films are not fiction or documentary, they’re hybrid. She’s an actress too, but she’s making films.” They got overwhelmed super quickly with people like me just because I’m too hybrid. You can’t put me in any box. Even the way I look: I look more like an actress than a director though I am a director. By the way, I didn’t do a single cover in France.

HARRIS: Are you serious?

DIOP: I won the Grand Prix.

HARRIS: Yes. And there’s a lot of firsts with regard to that win too, but that doesn’t matter.

DIOP: Of course. This is what I mean by “20 per cent.” Growing up in France, I’ve always had the feeling, of course from the incredibly rich legacy of my family, that my uncle, Djibril Diop Mambéty, my dad Wasis Diop as a musician and my mother as a French white woman who was a photographer were so ahead of their time that, to me, it was kind of like living in the future. But I have my own path to follow, and I can’t wait until France acknowledges me for who I am. I keep moving forward. In New York, beyond my skin color, I’ve always felt respected as a filmmaker and artist. And that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a major problem with racism here. It’s just dealt differently.

HARRIS: In the arts world, there’s a greater space of mobility for a Black artist in America than I think almost anywhere else in the world.

DIOP: The first time that I’ve experienced the art scene with Black people is in Los Angeles at The Underground Museum. It was five years ago, and I was 36, which is not that young to experience this. It never happened to me in France. Thanks god, I breathe better for the next generation because things are finally changing in France. More blacks artists and curators.

HARRIS: And now you are building on it. I watched Dahomey, and it does speak its own language. There’ve been experimental Black filmmakers for a very long time—Camille Billops, for example, who also mixes documentary and fiction, or William Greaves. We don’t have to name all of them, but this is the first time I’m seeing major festivals and major studios embrace Black experimentation without apology, without relegating them to the corner.

DIOP: Exactly.

HARRIS: Your film winning the big prize in Berlin was an amazing thing for the community. What do you think has emboldened you, after the success of Atlantics, to not play it safe, but to instead keep digging into questions and pushing yourself?

DIOP: When it comes to my art—my language, what I should defend, what I should stand for—I have no fear. Of course, the journey of Atlantics changed the game, basically. To me, making films goes beyond cinema; it’s really about pushing the frontier. It’s political. I chose to become a filmmaker to take control over the narrative. It’s funny, I suddenly have the image of a player on a soccer field.

HARRIS: A soccer pitch, yeah. You move your way through it. I keep thinking about the amount of friends who told me about Mati Diop before I knew Mati Diop. They were like, “Oh my god, Jeremy, you’d really love this artist.” That’s a credit to the time you spent being an artist in film, whether that’s as a director, an editor, an actress, whatever.

DIOP: Originally I wanted to be a singer, to become a musician. I’ve also acted in films. The reason I took another path is that, at the time, these fields seemed too much under the control of men and I didn’t want to limit myself to being the subject of their desire. Choosing to become a filmmaker meant choosing the freedom to write my own story, without compromise. Speaking of compromise, I can’t help but think of my uncle’s films, which were a great inspiration to me. I don’t often refer to my uncle because that legacy is so obvious, but what he did is insane.

HARRIS: It’s truly insane. I think you should always talk about it because Isabella Rossellini said something really beautiful recently about how, when she was growing up, she used to really hate that everyone knew who her parents were, how it was a shadow cast over her before she went into any room. But now she feels herself yearning to say their names more and more because so many generations don’t know about Neorealism, or that her father was the face of it.

DIOP: Exactly. I feel the same way. But because I dedicated a film to Touki Bouki called A Thousand Suns,I feel I’ve paid tribute, in my own way. The film is actually more of a confrontation with this generation that was bold on many levels but didn’t took the time to transmit anything to us. I guess they were too busy dealing with their own struggles as Black men trying to exist in the western cinema industry. You asked me about the boldness of coming back with a second feature and doing it exactly how I want. I think it’s part of my personality as a woman, as a filmmaker, but it’s also part of who we are as a family. We are game-changers. Also, with the credibility that Atlantics offered me, it gave me more freedom. I’ve always considered myself an artist in service of a political gesture or purpose, so my films were always political. But the political dimension should not necessarily be austere. I love comedy. Jordan Peele is my hero. It’s a bit naive to say it like this, but I feel like I should rise to the occasion of my era.

HARRIS: That’s beautiful. In the 1920s, for example, surrealism came to the forefront. The Harlem Renaissance came. And of course, a lot of the things we remember from The Harlem Renaissance, when you actually go through the libraries and read all the books, they were horny and funny and weird. We have to recognize the importance of the era we’re in, the fact that it’s shifting, and force ourselves to shift, too.

DIOP: Exactly. And also, in terms of form, it’s all about which form to give to all this mess. My ideal was to find a movie that was both completely cinematic but totally rooted reality and the present times. Dahomey came to me when I heard the news of the 26 royal treasures returning to the Kingdom of Dahomey, and it was in alignment with where I wanted to be as a filmmaker, which is to continue to explore the aesthetic and sci-fi dimensions of my cinema but still super grounded in the real deal in the case of that colonial legacy. I have this image of a huge speaker from Africa, from an amphitheater. I feel it’s time for the story to be told from this place. At the end, the most important thing about this film is not so much the question of restitution, but rather from which place the film speaks to us.

HARRIS: Totally. There were things about your film that made me question my relationship to restitution in a real way. I think about the Dahomey people in general: this is a warrior class of Amazons, and they went to war, a war that the fish king dreamed up and knew he was going to lose, and then they lost. And because they lost that war, all this stuff went away. And it’s like, “What was their relationship to their spoils of war?” In some ways, should they just let them have it all because they did win them in war? It was a really fun way to think about all of it because you gave us that amazing moment of debate in the middle of the film. There’s so many things I want to ask you about the actual movie. But first, you read this article. But how do you get access to the 26 treasures?

DIOP: While I was writing Atlantics in 2017, [Emmanuel] Macron, our president, did a speech in Ouagadougou, which is the capital of Burkina Faso, saying that he’s the first French president who’s said that colonization was a crime against humanity, which was an important step. And then he said, “Within five years, a consequent number of artifacts from Africa should go home,” which was kind of earth-trembling to me. It was shocking because the level of trauma and denial in France just weighs down on you, killing everything. So I honestly felt the ground move under my feet. I had vertigo, and the vertigo also came from the fact that I realized that restitution had never really been something in my imagination. This is the legacy of colonialism: oblivion. So I was like, “Okay, the colonial denial trauma also had an effect on me, and I do have to continue to decolonize my own spirit and my own imagination.”

HARRIS: And also, to imagine that a president of any major western nation would actually attempt an apology feels like science fiction? It feels like something that would only happen in fantasy.

DIOP: Exactly! Well, shooting Dahomey actually felt like an anticipation movie ! Also, it was almost reminiscent of something that was blocked in a cave. It was both cinematic and post-traumatic. Anyways, so when I first heard the word “restitution,” I instantly imagined something I never envisioned before which is a sequence in which massive wooden cases were being lifted from a plane and dramatically deposited on native land. A very strong vision made of sound. And I felt, “This is going to be my second feature once I finish Atlantics.” And this fiction I had in mind became real and became Dahomey. By the way, I realize that in the dozens of interviews I’ve given in which I’ve revealed the fiction I initially had in mind before shooting Dahomey, this African mask telling its own story, no producer has yet proposed me to do it. And yet, I think this film should be made. Maybe we should write it ?

HARRIS: Let’s do it!

DIOP: I’m serious.

HARRIS: No, I’m dead serious too. One of the things I’m always obsessed with when I go to the fancy houses in Hollywood of woke-ish producers is the amount of African artworks they have. And you’re just like, “First of all, I don’t think you’ve ever been to Africa.” But why did you buy this? Why did you get this tusk, or this mask, and what does that tell the world about you for yourself? Do you gaze upon it in the morning? Does it just fade into the background, like every other piece of paint and picture in the house?”

DIOP: Right. I did all this digression to tell you that, when I started, when I saw the announcement of the return of the 26, I already had this fiction in mind. I jumped into the shooting of Dahomey, but the fiction was already in my mind. The idea of making the artifacts talk was already there, and I really wanted to structure the film—the artifacts and the students—like an opera.

HARRIS: And they harmonize beautifully. You do something really beautiful in this film, where it’s speaking a lot of new languages and a lot of languages that are completely its own. But one space where I thought the movie really sang was in the music. A lot of scores are championed as unique, but I’m like, “I know what they’re referencing.” In this score, it felt completely unto itself. So I wonder how you came to this score and this sonic landscape.

DIOP: I mean, the choices of Dean Blunt and Wally Badarou are hard even for me to explain, because it’s organic. I chose these four tracks very, very early in the process. I wrote the film with them from the beginning. Dean Blunt is basically the music I listen to the most in my everyday life. And Wally Badarou carries an imagination that, for me, is kind of like a large door. It represents the generation of my father. They’re musicians of the eighties and nineties who were African, who were really trying to transcend the essentialization of what African music was perceived as at the time. They were inventing the African music of the future, music which wouldn’t be assigned geographically. They’re pioneers, actually. So the music, what it carries historically and politically, is material that gives so much dimension to the voice of the treasures themselves. And as you know, the score is not only about the music; it’s all the silence around it, too. It’s pure dramaturgy.

HARRIS: Yes, completely. That’s how I look at producing. Producing is just dramaturgy. That’s all it is. And you feel that when you watch this movie.