Yohji Yamamoto

At a certain point, I stopped seeing my clothing worn by people on the streets . . . It seemed like they were being treated as museum items. Yohji Yamamoto

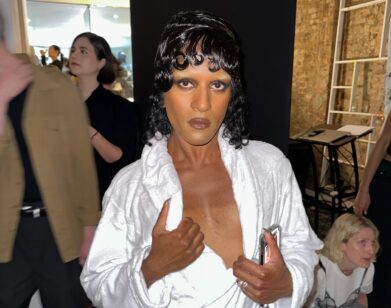

Athleticism is rarely a quality praised, or even acknowledged, in fashion. But it is also one that is hard to dismiss in a designer like Yohji Yamamoto, who once concluded a runway show with a martial-arts demonstration in which he appeared to karate-chop a male model.

Along with Issey Miyake and Rei Kawakubo, Yamamoto was, of course, at the fore of an influential wave of avant-garde designers who emerged from Japan in the 1970s and early 1980s. Born into wartime Tokyo in 1943, he first studied law, but opted instead to go to work for his mother, a seamstress, and enroll in Bunka Fashion College. It was after a brief sojourn in Paris that he established his first label, Y’s, in Tokyo in 1972, debuting his eponymous line back in the French capital nine years later and blowing away the tight dresses and padded shoulders of the sartorial moment with the billows of dark fabric and a brand of intellectual playfulness that instantly earned him a place as one of the most forward-looking, paradigm-breaking, and versatile artists in contemporary fashion. But for a man whose work has consistently been associated with the cutting edges of things, Yamamoto has always remained remarkably trend-phobic, choosing to operate within a framework that has less to do with the whims of seasons and more to do with the development of ideas, as exemplified by his frequently loose, asymmetrical cuts, enveloping drapes, ample uses of black, and recurring flirtations with sexuality and androgyny. In this way—as well as others—Yamamoto has always described his relationship with fashion as one built around a kind of tension that’s palpable in his clothes, where freedom (you can dream up whatever you want) and restriction (you are beholden to commerce, rules, reactions, and deadlines) are in a constant tug-of-war.

But back to athleticism: At the end of the 1980s, Yamamoto took up karate, eventually earning his black belt and embarking on a kind of sporting life that would undoubtedly inform another of his endeavors. In 2002, Yamamoto began collaborating with Adidas on Y-3, a line of sneakers, exercise clothes, and other active-minded pieces that applied the high-fashion sharpness of his main line to sportswear. As Yamamoto recalls, the idea for Y-3 first emerged when he requested some sneakers from Adidas for a show, which was intended as a subversive nod to the brand’s currency with street kids in Japan, who, at the time, were going through one of their periodic infatuations with triple-striped track suits. The conversation that ensued led to a discussion about Adidas creating some special sneakers for Yamamoto, which led to another discussion about more fashiony nips, tucks, and variations that could be applied to other kinds of athleticwear, and ultimately to the development of the entire line, which came to include accessories and even fragrances. Indirectly, Y-3 also paved the way for other fashion-sportswear brand collaborations (as well as the advent of the designer sneaker), and helped establish a stronger, more frequently traveled bridge between the runways and the street—the impact of which, among other things, has been a profound increase in the speed with which the ideas and attributes of high fashion wend their way into how people dress in their daily lives.

The merging and intermingling of these disparate worlds has become an area of frequent exploration for a number of designers on both sides of the aisle—and one that Yamamoto has continued to examine, and even comment on, in his own work. In fact, it was at the end of a laser-lit, superhero-themed Y-3 show in 2010 that Yamamoto tapped into his considerable gifts as both a martial artist and a performance artist in delivering the aforementioned karate-chop, a sudden blow that leveled his opponent—after which the designer himself was swiftly taken out by one of his female models.

Filmmaker Wim Wenders, who memorably captured Yamamoto in his own habitat for the 1989 documentary Notebook on Cities and Clothes, recently reconnected with the designer, now 69, in Tokyo to discuss 10 years of Y-3, how he maintains his edge, and why it’s still best not to mess with him in a dark alley.

WIM WENDERS: Where are you right now?

YOHJI YAMAMOTO: I’m just finishing up in my room at the office.

WENDERS: You always work so late.

YAMAMOTO: Where are you?

WENDERS: I’m in the office, too—in Berlin. But it’s in the middle of the day here. So you had a long day again as usual?

YAMAMOTO: Very, very busy—and yes, that’s the usual. You know, at this point, I’ve become like a clothes-making machine.

WENDERS: I don’t know anyone who keeps the hours that you keep. But it’s good to hear your voice. I wish I could be in Tokyo with you right now. We could go play some pool and eat some blowfish.

YAMAMOTO: Yes, I remember—the poison fish.

In my main line, there are boundaries and rules, whereas in designing for Y-3, I am more free. I can work without any taboos. Yohji Yamamoto

WENDERS: You took me to the restaurant that served that poison blowfish, and I thought, “This is very, very dangerous, because any little mistake the cook makes . . . You die.” [both laugh] I was so nervous—even the dessert there seemed like poison dessert. But we survived it.

YAMAMOTO: Yes, we did. Do you remember the bet?

WENDERS: Which one? [laughs] Oh, the pool game.

YAMAMOTO: Exactly.

WENDERS: I lost—or I think I lost. Do you think you lost?

YAMAMOTO: I think I won the bet.

WENDERS: Yes, you won . . . Absolutely. And now it all comes back to me! We said that if I lost, then I would have to take part in a men’s show and go on the catwalk.

YAMAMATO: You still have to do it!

WENDERS: I will! I remember when Samuel Fuller walked in your men’s show in Paris. That was so fabulous! Sam was so proud to be showing your clothes. I would be, too—I’m doing it all the time anyway. I’ve had to fix some of the old suits because I’ve had them as long as we’ve known each other—or even longer.

YAMAMOTO: You are a very good dresser. [laughs]

WENDERS: I wasn’t before. Over the years, though, I have developed a sixth sense when it comes to who is wearing Yohji. I can see it right away.

YAMAMOTO: Well, recently, the new winds have started blowing to me. My company, my business, has been growing.

WENDERS: Thinking about the film that we did together, Notebook on Cities and Clothes: Do you realize that it’s almost a quarter of a century old now? Can you imagine? We were both young men when we made that movie. So many things have happened to you since then—and over the last 10 years, especially.

YAMAMOTO: Yes, yes. But at the same time, I feel like I have become a living fossil in the fashion world. Without even noticing it, in my own collection I have moved away from the street style. I was on a Japanese designers’ pedestal—considered a maestro. My design was getting closer to a couturier’s work, and I felt like I was missing something. But I always want to have a new challenge involved. I need to put myself to the test, and if I make mistakes, it doesn’t matter. What matters to me, instead, is making my dreams come true and putting them on display. At a certain point, I stopped seeing my clothing worn by people on the streets . . . It seemed like they were being treated as museum items.

WENDERS: Well, you’ve been designing for how long now?

YAMAMOTO: Around 50 years. I started working in Tokyo about 40 years ago, and I’ve been showing in Paris for 32 years.

WENDERS: So you are not a fossil, you are a dinosaur. [Yamamoto laughs] But a dinosaur that is in good shape.

YAMAMOTO: Well, for my next men’s show, you will have to walk on the stage.

WENDERS: Okay, just give me a call. I’m nice and thin right now, but don’t wait too long, because I’m going to gain weight again.

YAMAMOTO: [laughs] I’m planning to make a very strange fashion show right now in Berlin.

WENDERS: What is going to be so strange about it?

YAMAMOTO: I’m going to do a show by using my archives—my old work.

WENDERS: I think the last time we saw each other was at your beautiful exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum a couple of years ago. You showed some things from your archives there, too.

YAMAMOTO: The Victoria and Albert was an exhibition, though—a retrospective. But I’ve never done an archive show before.

WENDERS: You’ve been collaborating with Adidas on Y-3 for 10 years now.

YAMAMOTO: Yes, it’s 10 years already that I’ve been doing that.

WENDERS: I remember how excited I was when that started—I still have some beautiful vintage shoes from the first or second year. How did working on that develop?

YAMAMOTO: It’s been growing every year. We now have a whole team of five or six people who are involved in it. They all work with me on Y-3. It all happened spontaneously. In the beginning we just wanted to borrow some ‘three stripes’ trainers from Adidas for my Fall-Winter 2000-01 show. In Japan, the three stripes were everywhere, and the young crowd did not take them off even when it was time to go to bed. So I decided to ring up Adidas and ask them. I was sure that they would refuse and was pleasantly surprised when they said yes. Then we started discussing with their designers how the sportswear of the future would look and decided that we would need high-tech fabrics, bright colors, and fashionable silhouettes—in short, everything the full-price prêt-à-porter collections had. So that’s how Y-3 came about. For Y-3, I am creating something that has never before existed in the world . . . It developed naturally and grew the way children develop and grow. More things were added—accessories, hats, bicycles, soccer balls—but the original idea has not changed. You have to treat Y-3 like it is an independent human—in that way, the brand already has its own character. The sports world and its technology seek practicality and functionality, attempting to reduce excess, while fashion is seeking the opposite. So together with Adidas, we created something that did not exist before—and completely projected the future. Adidas is a very personal inspiration to me. It has enriched my creative life. It’s an exchange between different cultures, different ideas, and most of all, it is teamwork. Japanese and German people are intelligent sorts—our working rhythm is the same. So Adidas and I, we just like each other. So what are you doing right now?

I always want to have a new challenge involved. I need to put myself to the test, and if I make mistakes, it doesn’t matter. Yohji Yamamoto

WENDERS: I’ve been working on this documentary about my favorite photographer, Sebastião Salgado. He and I have been discussing something that I wanted to ask you about. If you’re working as a filmmaker, a writer, an artist, or in any creative field, as you become older, you often realize that, in a strange way, you always do the same movie, write the same novel, make the same painting. There is a language to your work that you can’t cast aside—it’s in you and it’s who you are. Do you feel like that’s true for you in any way? Do you feel like you’re designing the same clothes over and over? Or do you feel like you can still totally reinvent what you do?

YAMAMOTO: I feel like I’m doing the same thing every year. In my main line, there are boundaries and rules, whereas in designing for Y-3, I am more free. I can work without any taboos. But then there is also a schedule to fashion—the deadline is always set. So maybe the fashion business is a good business for me in that way because I’m basically lazy, man.

WENDERS: Well, for a lazy man you are the worst workaholic I know. Do you at least take some days off after a show?

YAMAMOTO: I have no imagination about holidays, vacations, or retiring life. I can’t imagine about those things.

WENDERS: I am the same way. Donata [Wenders’s wife] tries to convince me that we should have a holiday, but I don’t know how to do it. It’s a difficult concept for me—to go somewhere and not do anything. Don’t you think it’s a strange idea, the holiday? To travel somewhere in order to—

YAMAMOTO: Not to do something. Yes, it’s very difficult for me, too . . . But when you describe it the way you just did, I like it. [both laugh]

WENDERS: Do you still play guitar?

YAMAMOTO: Not anymore. I no longer have emotion for playing guitar or making music. If I do it again, then maybe the title of the song I play will be “Goodbye.”

WENDERS: Let me know if you change your mind, because I loved your music. I wish I could still play the saxophone but I’ve lost the habit.

YAMAMOTO: The saxophone?

WENDERS: Yes, I used to play the saxophone. But it’s been too long since I’ve played, and if you don’t keep it up, then it’s probably the same as what happens with your fingers and playing guitar—your mouth doesn’t have the feeling for it anymore.

YAMAMOTO: Yes. You have to be dedicated. I also don’t have much time now because Keiko and I recently started living with a baby dog, which is a big responsibility. I cannot go out at night, because none of the coffee shops or restaurants accept animals in Japan. So when do you finish the film?

WENDERS: I’m still working on it, so hopefully we will finish this spring. I just shot with Salgado in Paris, and now we’re going to Brazil in a couple of days, to his hometown to shoot with him there. He’s a beautiful man and he does fantastic photography. But Donata and I might be in Tokyo later, in the next few months, so maybe we can see then if I cannot beat you at least once in pool. Maybe you will give me a chance.

YAMAMOTO: Oh, I’m sure you will lose again. [laughs]

WENDERS: I’m already intimidated—I will have to practice. Are you still fighting? Are you still doing martial arts?

YAMAMOTO: Not really. The best moments in my life recently are just before going to bed. Those are my happiest moments.

WENDERS: So your black belt is no longer active?

YAMAMOTO: I’m not sure. But if a crazy man wanted to have a street fight with me, I still might be able to beat him.

WIM WENDERS IS AN ACADEMY AWARD-NOMINATED GERMAN FILMMAKER AND PHOTOGRAPHER.