Tomas Maier

One of the most indelible images from the spring 2010 collections was the finale of the Bottega Veneta show. A trio of gowns floated down the catwalk in a cloud of color so luminous it seemed to suck the light from the room. The fabric—a synthetic chiffonproduced in Japan—is one of the lightest known to man, so fine, in fact, that it can only be hand-cut with lasers. Science aside, it was the translucent beauty of the dresses that drew a gasp from the audience. And one can only imagine how satisfying that would be for Tomas Maier, the man behind the wheel at Bottega, the Italian label whose subtlety is an antidote to the excess of an era.

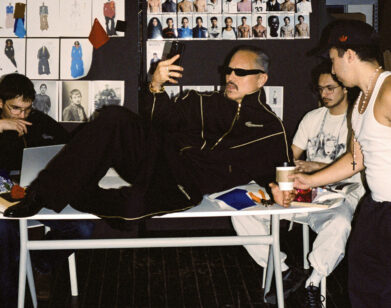

Born in Germany on the edge of the Black Forest, and now a resident for at least half the year in Palm Beach, Florida, Maier is something of a paradox—a laconic sensualist. For nine years before Bottega, he was a designer at Hermès, where Jean-Louis Dumas imparted the formula that the 52-year-old Maier lives by: passion and patience. In other words, everything takes time. So for the past eight years, Maier has slowly, steadily reconfigured Bottega as the idiosyncratic apogee of 21st-century affluence. The label’s original modest motto—“When your own initials are enough”—is perfectly in tune with the designer’s own yen to keep himself as invisible as possible. So it follows that he’s not much of a talker. But he scarcely needs to be when the distinctive union of craft, technology, and desire that he has brokered speaks so effectively on his behalf. Still, there was much to say when we met in Bottega’s swanky new Milan headquarters, a few days after the spring show.

TIM BLANKS: Did this last collection feel special to you, like a big move forward?

TOMAS MAIER: No, because I think every collection is always a move forward. It’s the same work—the process is always the same. The interesting thing is to try to achieve a certain nothingness.

BLANKS: I thought it was interesting that the colors were so strong in this collection, because they were also concealed. A dress would open quite slyly and reveal intense color underneath. It struck me that there was some kind of psychology at work—the outside is serene, then there’s this tumultuous little streak on the inside. Do you think like that when you’re making clothes?

MAIER: It’s the moment when you’re making the clothes—“Doesn’t this need that?” That’s how it comes. It’s not from, like, thinking for hours. Most of the things happen when you are in the fitting. When you make clothes, the fitting is the decisive moment. BLANKS: You mentioned nothingness. Is that really your goal at the end of it all?

MAIER: Well, that’s what’s interesting. You know, I’ve been in clothes-making for 32 years. Think how many times I’ve made a blazer in my life, how many shirts I’ve made. What’s interesting is to strive for a certain perfection, and what’s perfect is nothing.

BLANKS: As in complete purity? Or is it that the more “nothing” the clothes are, the more “something” the person wearing them is?

MAIER: Yeah, I mean, the better the clothes are, the less you see them.

BLANKS: Is that the ultimate craftsmanship for you, to actually make the craft completely invisible?

MAIER: It’s the ultimate for me not to see how it’s made. I find it vulgar when you can distinguish how something is made. I used to be a student at the Chambre Syndicale [de la Haute Couture] in Paris, and once I got to go to a Saint Laurent couture show. Everyone was always talking about how fabulous the tailoring was, but I was transfixed by this one particular dress. It was just a piece of fabric, but as the model was walking, you didn’t know how she got into it, how it closed, where the seams were, and that, for me, was perfection. It stayed with me as a lifelong vision. So this is why I’m making bags that don’t even have a seam. But many people don’t get that. They run through the showroom and go, “He did yellow bags this season.” That’s fine. Not everything needs to be visible to everyone. But personally, that’s what makes my work interesting to me. The whole fashion thing is not that interesting to me. The overall circus is not my universe.

I’ve been in clothes-making for 32 years. think how many times I’ve made a blazer in my life, how many shirts I’ve made. What’s interesting is to strive for a certain perfection, and what’s perfect is nothing.Tomas Maier

BLANKS: So in the end, this is all about you, your personal quest?

MAIER: No, it’s about what I’m doing at this company and what we can achieve together, and the beauty of being here in Italy. I think the only other place you can work like this is France. There’s a supreme know-how and a desire to achieve that doesn’t really exist anywhere else. You can’t make clothes like that in America, because it’s just not in the tradition.

BLANKS: Would you agree that there is a certain ruthlessness about the quest for nothingness? You need to be quite obsessive in your pursuit of it.

MAIER: Yeah, it is kind of obsessive, absolutely. But it’s like that for everybody who works on my team. We all have the same drive. Nothing is impossible. Whatever idea comes up, we always try to make it. Sometimes it doesn’t work because it’s just not technically achievable. But you can always make things better, more contemporary with the construction, the inside, the weight, and all of that.

BLANKS: I always come back to Alfred Hitchcock with you. It’s a number of things: the foreigner’s point of view, outside looking in, the psychology, which I always find a little bit twisted. . . .

MAIER: And the color sense. I look at those movies from time to time, and if you haven’t seen one for a while, say, North by Northwest [1959], that scene in the train compartment, the colors are so fabulous between the man’s suit and the woman’s dress and the upholstery in the train. You know, everything is like [lip-smacking noise of appreciation]. It’s magic.

BLANKS: To me, your quintessential woman is the Hitchcock blonde, and your man is the Hitchcock hero. With Hitchcock, there’s always purity offset by carnality. For example, Grace Kelly is a glacial blonde beauty, but she’s going to have sex with the guy, with fireworks and trains going into tunnels. That’s a little bit the mood of your collections as well.

MAIER: Sure, it’s always very suggestive. The Maier woman is not a woman who doesn’t have fun. My woman is not a woman who doesn’t have a life. I like clothes to suggest something. I’m gay, but so what? I still have that sensibility that I like to look at a beautiful woman, and I’m as intrigued as any straight man. I probably look even harder because I like what you don’t see.

BLANKS: So you like this idea of revealing something unexpected?

MAIER: Absolutely. There’s another little vision in my life, going into a restaurant in New York years ago: All the women are sitting in their little strapless dresses with their cleavage, and there’s this one woman in a sleeveless turtleneck and pants. And I can tell you that every man in that restaurant looked at that woman’s arms. It was hypnotizing when everything was covered up. Just the face, the conversation—and you see the arms. And the arms and the hands become an obsession. I like that.

BLANKS: I’ve always thought the big picture in your work is something to do with America, applying the outsider’s eye to really traditional American values. Plus, you live in Florida, which to me is so much more American than living in New York or Los Angeles. How do you feel about that?

MAIER: I’m more European than anything. I’ve lived in America for 10 years, and I live in Florida because I like to be outdoors. I’m there two weeks out of the month. I live a week in New York, and I live a week in Italy. And when I’m here in Italy, I come to work at eight in the morning and usually I leave work at 10 o’clock at night. I don’t even breathe the air. So that’s why I like to live outside.BLANKS: How much of what you do is a reaction to how and where you grew up in Germany?

MAIER: Where I grew up, we spent a lot of time outside, did a lot of hiking and outdoor things. I moved to Paris when I was 19, and from then on, it was exactly the opposite. On the weekend, you go to the galleries, the museums, the movies. And there was a point in my life in Paris where I thought, “I’m not going to be like all of these friends I’ve had who are now at this certain stage in their lives, and they are all unhappy with themselves because they never get out in the fresh air or the sun, and they get so disconnected from their bodies that they have to just layer and layer and layer like onions. I am not getting old like that.” So Andrew [Preston, Maier’s partner of two decades] and I moved to Florida, to get some air. Am I going to live there forever? No, I’m not. But I have a warehouse, all white, concrete floors, a big, big space with very high ceilings and nothing inside. And that’s where I go to work, and I like that because I just like to be alone and quiet. Is it explainable as a typical fashion designer? No. But am I a typical fashion designer? I don’t think so.

BLANKS: To walk your dogs on the beach every day before you go to work. To me, that would be heaven!

MAIER: That’s what I do. That’s my luxury. The food’s not so good in West Palm, but you can’t have it all.

BLANKS: And how does that very personal interpretation of luxury find expression in Bottega Veneta?

MAIER: I think it’s all personal. A garment is the same thing. It’s a personal matter. It might look like nothing to somebody else, but to you it means something. I like simple, I like quality, and I like less. Do I like a certain aesthetic? Yeah. I think what you see in the show is really reflective. I’m working for a woman, not a lady. What I hate the most is that “lady” talk. You know, when I read a review, “The lady wears a Bottega . . . .” What lady? It’s the same girls who are walking the runway an hour later elsewhere. But probably it is just the sophistication in our material, the nuance of the color, or the quality of the makeup or the hair that make people think that way. Most people just don’t understand simplicity.

Tim Blanks is a veteran fashion journalist and contributing editor at Style.com.