The Agony and Ecstasy of Thien Venus Milo

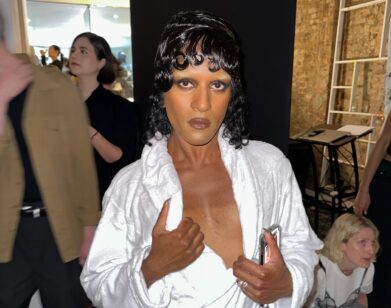

Twenty-four-year-old Thien To, who makes clothes under the name Thien Venus Milo, is a designer to watch. This June, for her senior collection at Philadelphia’s Drexel University, To presented seven edgy and opulent couture looks in silk, satin, leather, and tulle, inspired by the story of Alice in Wonderland. Molding laser-cut plexiglass forms into leather and incorporating patterns used in welded iron railings into her red, white, and black designs, To created an imaginative eveningwear collection with ornate details.

“My inspiration comes from my fantasy but also from my turmoil,” says To, who emigrated to the U.S. from Vietnam six years ago. “A lot of people don’t understand me, and I went through a lot of depression until I actually brought this collection to life.” She points to where serpentine black designs meet pale tulle on one outfit. “The black represents one of my down times. Depression was eating up my energy. The part in black leather is taking over my body.”

For To, making clothes is not just a trade or an art form, it’s also therapy. She credits the avant-garde designer Alexander McQueen for getting her interested in fashion. “McQueen said he wanted women to be scary. He wanted women to be powerful,” To explains. “I don’t really want women to be scary as much as I want them to be respected.”

For her presentation, To cast her models in dramatic roles, as queens, princesses, and warriors, in part because she sees clothes as potentially transformative: Costumes can protect, empower, and embolden the wearer. “I have a lot of corsets in my collection because I believe when a woman wears a corset she always stands straight,” she says. “Up straight is a powerful pose. People say that corsets manipulate the body. If a corset is done right, it gives the woman the power.” Respected women, she seems to say, may hold others at a slight remove. Dressing monarchs and warriors also allowed To to exercise her conception of elegance, not to mention her skills as a painstaking technician.

The collection is memorable not only because of its unabashed sexiness and its simple three-color palette, but also because of the story it seems to tell. It evokes the pleasure and the torment of growing up, with each look in the collection conjuring a specific moment in a girl’s transformation into an adult. The way that designs and cutout motifs repeat and subtly evolve from the beginning to the end of the collection indicates the erratic progression involved in coming of age.

There’s a fanciful juvenile period shown, for example, by a single red leather sleeve with red hearts and flower-pattern cutouts atop a white high-low gown. Throes of crisis are exemplified by a woman warrior in flouncy white sleeves, a tight black leather corset top, and black leather pants. Newfound self-assurance is embodied first by a model in a womanly red leather corset and voluminous white satin skirt over a tulle petticoat, and then by the most theatrical—and elaborate—look in the collection, an imperial queen in a black leather and organza corset-like top with filigreed leather bands sinuously winding over the top of a floor-length satin skirt that had been overlaid with charcoal-grey tulle. Her final piece is an off-the shoulder bridal minidress in white, with a long crinoline overskirt.

“In Vietnam,” To explains, “there is a village where women do incredible embroidery. When a woman wants to work in that field, she first has to be an apprentice, and then she has to be initiated into that career. When she is initiated, she has to make two dresses—a life dress and a death dress. The life dress is what she’s going to wear at her wedding. And the death dress is what she’s going to wear at her funeral.”

“This is my life dress,” she says, pointing to the wedding dress that ended the show. “And this is my death dress,” she says, pointing to the black and white dress of her most forbidding queen.

As a child in Ho Chi Minh City, To enjoyed drawing, but was also interested in math and engineering, thinking perhaps she would become a doctor. The transition of moving to the States, where she chose to go back to high school at eighteen, in part to improve her English, was hard. While helping with costume design for a play her school was doing with the Philadelphia Young Playwrights, To was struck by how costumes seemed to influence the wearer’s personality. “At that time, I did not want anybody that I ran into to know that I was depressed, so my goal at that moment was to find a way to help people stay happy with whatever their situation is,” she says. She found solace when she resumed making the manga-style drawings she had begun in her earlier years, this time using the style for fashion illustration. Her choice to study fashion design was a surprise to those around her, but her realization of how clothes can affect a person seemed both significant and practical.

“Sometimes what a person wears can touch their emotions a bit,” she says. “I know I can make my work meaningful to people.” For now, To is open to limited commissions because of her day job as a technical designer. She is adventurous in spirit and audacious in the design of sensuous forms. But To offers a pragmatic takeaway when it comes to what she’s learned by growing up: “People need to share their thoughts on beauty, fantasy, and art every day.”