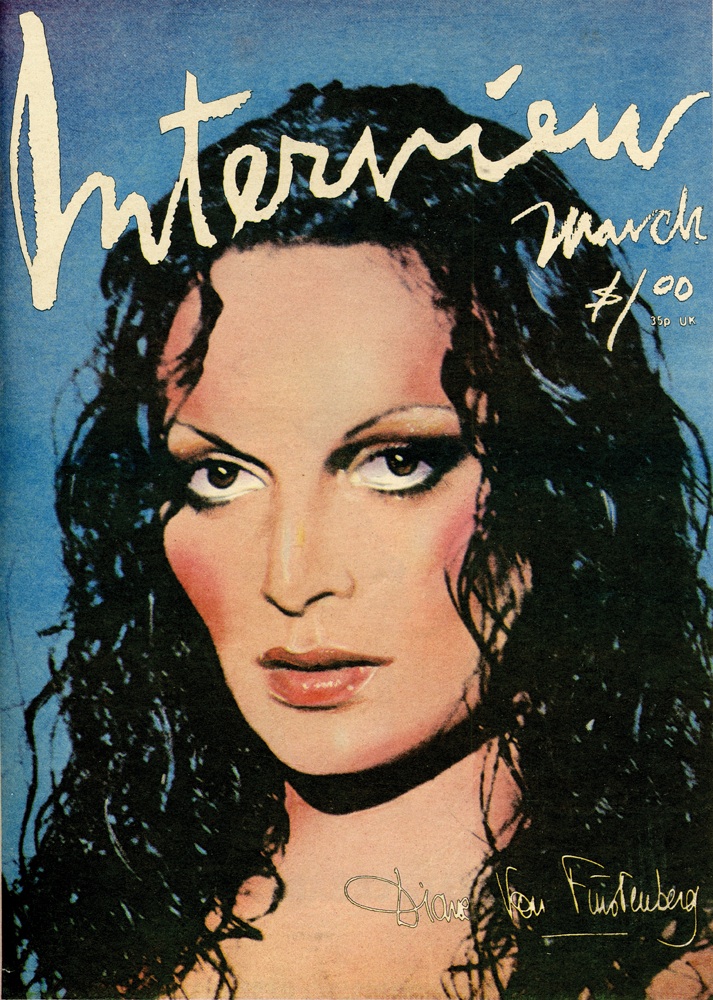

The Look: Diane Von Furstenberg

ABOVE: ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHY: ARA GALLANT. COVER PAINTING AND DESIGN: RICHARD BERNSTEIN.

When Diane von Furstenberg introduced her signature wrap dress in 1974, the sultry Belgian-born beauty, recognizable by her sharp cheekbones and European élan, was on the verge of becoming not only one of the most bankable designers of the decade, but also an icon of the social changes of the era-a liberated woman reclaiming her independence in matters of beauty, sex, and financial freedom. Forty years later, now the acting president of the CFDA, von Furstenberg is still living her dream by doing things the DVF way. The exhibition “Diane VON FURSTENBERG: Journey of a Dress” is currently on view at the former May Company department store in Los Angeles, celebrating the anniversary of the wrap dress that started it all, and the woman who made it happen.

HARRY BRANT: My favorite look was your first Interview cover from 1977.

DIANE VON FURSTENBERG: Andy wanted to do this cover—it was not long after I was on the cover of Newsweek [March ’76]. My friend Ara Gallant, who I love, love, love, used to be a hairdresser—he did all the beautiful hair of Veruschka on the Avedon shoots—he became a photographer. We shot at night in the studio. It was late, it was the ’70s. I had a bodysuit, and he cut my bodysuit. He always made you feel really sexy. My hair was straight, we shot the picture, and then he said, “Okay, now wet your hair.” I said, “It’s gonna get curly.” He said, “It doesn’t matter, we already have the shot.” So we wet my hair, and he took the picture as it was drying. Of course, when he showed me the two pictures, the second one was clearly the best. From that moment on, I wore my hair curly.

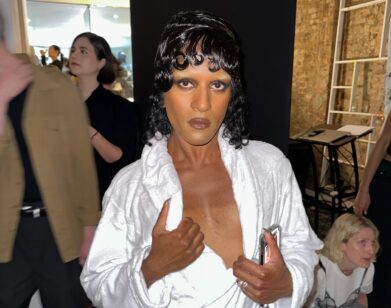

BRANT: For me, that picture is everything about the time. It’s got so much sex appeal. Even now, when I look at some of the new Tom Ford beauty looks—the really blushed, bronzed, greasy, highlighted cheeks and the deep, smoky eyes—I see a return to ’70s glamour.

VON FURSTENBERG: Everybody is thinking about the ’70s. The New York Times asked me to write an op-ed about the future of fashion recently. I’m celebrating my anniversary—

BRANT: The 40th anniversary of the wrap dress.

VON FURSTENBERG: So I was thinking, “Okay, in the ’70s, what was 40 years before?” The ’30s. Before then, it was art nouveau, and then all of a sudden it was Mies van der Rohe. The ’30s were always an inspiration for our generation. Some decades will always be inspiring. Like the Empire moment during Napoleon.

BRANT: You know that Joséphine [Bonaparte] used to encourage courtiers to dump buckets of water on the Empire-style dresses so they’d cling? I love that.

VON FURSTENBERG: There are these moments, and they always have to deal with freedom. In the ’70s we thought we had invented freedom. It was the decade between the pill and AIDS. For us, it was all about liberation. My dream was that I wanted a man’s life in a woman’s body. And I got it. I was very lucky I was able to live my dream.

BRANT: Did you always know you wanted to be a designer?

VON FURSTENBERG: No. I did not know what I wanted to do, but I knew the woman I wanted to be. I did not know how I would express it, but I knew the feeling I had. I just wanted to own my destiny. You have to find an odd way of expressing something so that you create your own identity. That’s the most important.

BRANT: What was it like hanging out with Andy in the ’70s?

VON FURSTENBERG: He would’ve loved you. He would’ve been crazy about you and your brother. Andy did not speak very much. He was a voyeur; he was the one with the tape recorder, taking your picture. He never expressed himself at all. He would say, “Gee, that’s great.” Andy was like parsley, he was everywhere.

BRANT: A wallflower.

VON FURSTENBERG: Completely. But he was such a visionary. He saw our time before we did—the branding, all of the iconography, all of that. He would’ve gone insane with Instagram, with Facebook. He was social media before there was social media.

BRANT: What do you think about celebrity culture now? You’ve become a very big celebrity.

VON FURSTENBERG: You know, celebrity is such an unattractive word. It feels so empty. It’s like if you put varnish on something that isn’t anything, it stays nothing. It’s so easy to make fun of Paris Hilton, right? But Paris Hilton is a good girl, and she’s a working girl.

BRANT: I love Paris.

VON FURSTENBERG: I do too. At the end, it’s how much you work at it. Celebrity itself is unimportant, but if you use its success to inspire others to do things, then it’s fine. The rest doesn’t count because at the end, what stays behind are your family, your children, and your body of work.

BRANT: I agree.

VON FURSTENBERG: I always remember, for me, a symbol of real glamour: When I went to Japan for the first time, I wanted to go see a Kabuki. I wanted to see Kabuki because of the makeup, but actually, the makeup is not that interesting. It’s just a white face with red lips. But I asked to go backstage and I met this man, an older man, 60 years old, and he was sitting on the floor with a beautiful vanity mirror. They start to dress him, and he’s supposed to be a 16-year-old virgin. First he gets a big petticoat with the most incredible, intricate orange-and-green embroideries of birds, and then comes another petticoat of blue clouds. There’s this whole ceremony of layers, of incredible, intricate design and color. Then on top of it all, they put on something black, so when you see him onstage, you don’t see any of these layers. The spectator doesn’t see any of it, but it builds the character. You have to be serious at the base so you can be frivolous on top.