LAGERFELD

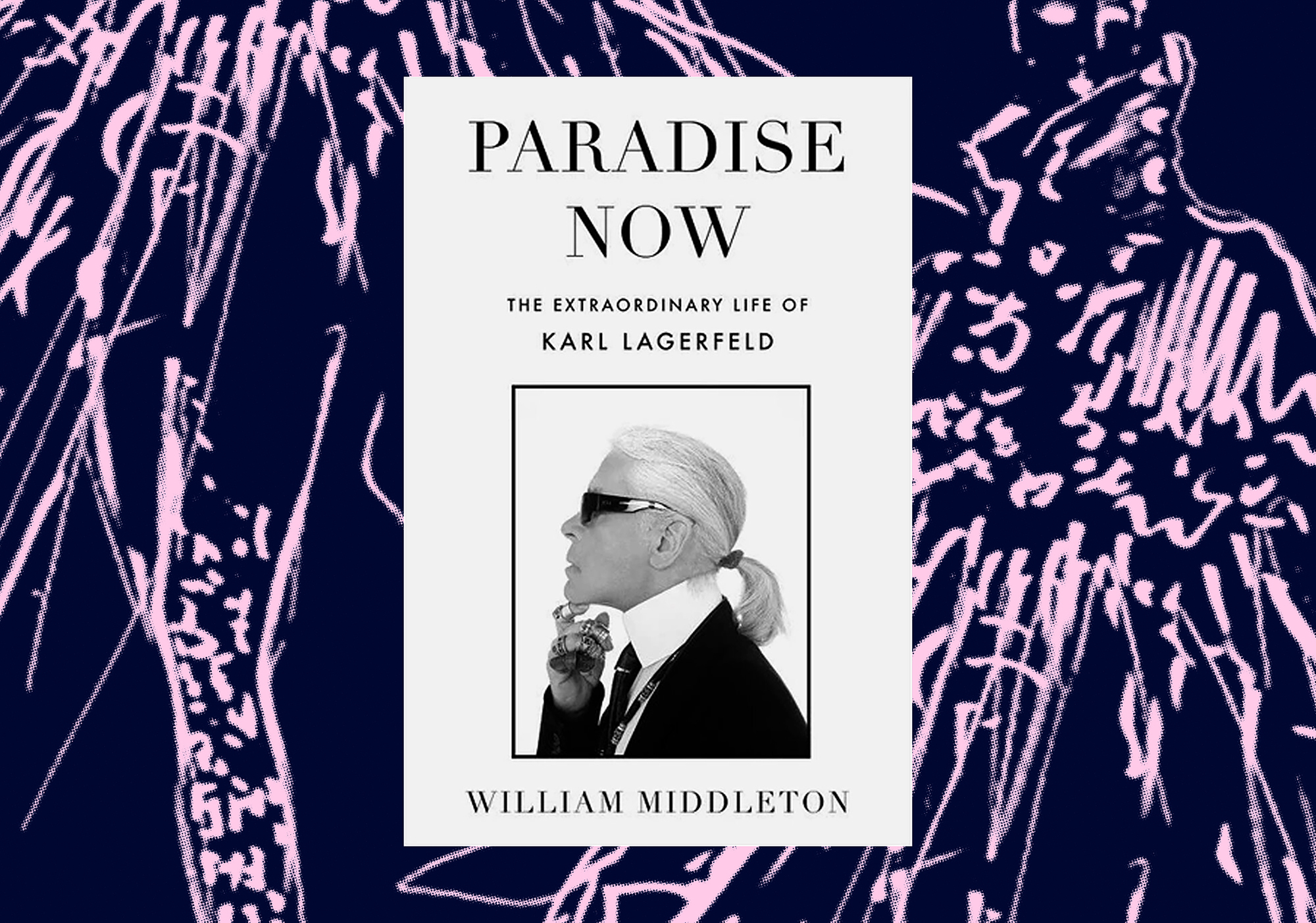

Biographer William Middleton Thinks Karl Lagerfeld Always Got His Revenge

From the outside, it would be easy to be a bit intimidated by William Middleton, the author of a new tome dedicated to fashion legend Karl Lagerfeld called Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld. He’s a chic American in Paris (he considers the City of Light his forever home), he has a stellar writing career, fabulous friends and contacts; plus, he cuts a very handsome visual over Zoom and in pictures. (Think retired, all-American football player who’s aware of the hierarchical seating of the Concorde.) However, upon meeting him, you quickly realize he is lovely, and though he has a city sophisticate aura about him, the Plain State virtues of unpretentiousness and authenticity have not left this son of the USA. Over Zoom, we have a fascinating exchange about the last ruling days of legacy fashion media, his years-long relationship with Lagerfeld, and the emotional complexity of contemporary fashion’s most irreplaceable designer.

———

CHRIS BLACKMON: I know that we’re supposed to talk about Karl Lagerfeld and the book, but I wanted to begin with you. Who is William Middleton? How did you get into fashion?

WILLIAM MIDDLETON: I’m originally from Kansas, so I shouldn’t be here in Paris. I always liked writing and studied journalism, moved to New York after the University of Kansas, worked for magazines in New York. I had always wanted to live in Paris, so when I was maybe 28 I was like, “Gosh, it’s time for me to be really serious about my career in New York, or move to Paris.” So I moved here. I was working for a magazine called Metropolitan Home, which at that point was a pretty cool design magazine. Living in Paris, writing for American magazines, you soon realize what people really care about is fashion, at least at that point in 1990. So I started writing more and more about style. Then after a few years, I was hired to work for W and Women’s Wear Daily. After a couple years, I became Paris Bureau Chief. So I was in charge of the daily newspaper of a women’s fashion business, and W, which at that point had just changed to a monthly magazine. I don’t consider myself a fashion writer exactly; I came to fashion really through Paris.

BLACKMON: So you basically got to live the last gasp of the magazine era, where magazines and publications like WWD really ruled the roost. Of course, we can throw Condé Nast in there. Tell me about those days, because I hear that they were quite fabulous.

MIDDLETON: Well, at Fairchild, we were always a little more sensible than other magazines. Condé Nast and Hearst were the ones who were really blowing it out, I think. What was super interesting is just the weight that fashion media had at that point. W and Women’s Wear, yes, but also Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. The weight that they carried in the industry was fascinating. It’s been interesting to see in recent years the number of influencers and TikTok-ers in the front row, because before it was just editors. Editors and buyers, that was it. We are not at a point where magazine editors have the same kind of authority they once did.

BLACKMON: When did you start to feel that shift?

MIDDLETON: I moved back to New York in 2000. Then in 2001, I started working on my first book. I moved down to Texas to work on it for, say, 15 years, and when I was removed from the world of fashion, certainly that’s when that shift occurred.

BLACKMON: When you got back, did it feel like a rundown Versailles?

MIDDLETON: Well, yeah. There are still amazing editors out there, and I hope that there are people putting out magazines and interesting newsletters. But it’s interesting to me, I have a friend who has become a men’s influencer, and he has, what, a million followers on Instagram or something? He has, in a sense, the same weight that Liz Tilberis had in Harper’s Bazaar in the 1990s. A lesson from Karl, I think, is don’t focus on what was; focus on what is and what’s going on right now. That’s where the title of the book comes from, Paradise Now. Because Karl was very good at not being nostalgic.

BLACKMON: He was a great survivalist for sure. You could have picked any topic for your next book. Why Lagerfeld?

MIDDLETON: I knew Karl beginning in January 1995, when I was working for W and Women’s Wear, and almost from the moment that I met him, what was so fascinating for me about Karl was his connection with culture. Karl knew everything about everything that was going on in terms of art and music and cinema and literature and design. Karl was so plugged into the culture of his time, and I fairly quickly developed a good friendship with him and a working relationship. I tried to make it clear in the book that I was not in any way his best friend, but we did quite a few stories together and I liked him and he, as I understand it, liked me. So I was just always fascinated by Karl, and he, as you probably know, was not interested in having a book written about him while he was alive, because he didn’t like anything that focused on his past. He was someone who was very much, as I mentioned earlier, tied to the present and thinking about the future. I always felt that was a little disingenuous, because no one knew more about history than Karl, but the difference is that it was his own personal history that he wasn’t interested in. Because for Karl, focusing on your past is suggesting that your life is over.

BLACKMON: Karl’s inspired so much already. Jared Leto is supposedly in talks to make a film about him. There’s the upcoming Met exhibit. There are four or five books already done on his life. In such a crowded field, what did you think you could contribute to the discourse around Karl?

MIDDLETON: It’s a good question. From the beginning, I wanted it to be a cultural biography of Karl. As I mentioned, I have long been fascinated with Karl’s connection to culture, so we wanted this book to really focus on his intellectual and cultural development. I think it does an effective job at really explaining how Karl became Karl. What books were important to him when he was growing up? We all know that he was interested in the French 18th century from an early age, but why and how? One of the great pieces of direction I was given at the very beginning of this process was from my editor at Harper Collins who said, “We want to feel like we’re in the same room with Karl.” It sounds very obvious, but it was super helpful. Because Karl was so effective at crafting his own image. You just mention his name and you see the silhouette, you see the silver hair, you see the ponytail, you think of the clever, bitchy comments. But it was very clear to Karl that was a performance, and so the job of a book is to document that public image but also look behind it.

BLACKMON: I’m very interested in the process of writing the book. Karl was a lot older than us, and therefore a lot of people who were firsthand witnesses have passed on, or their memories have faded. And Karl was very good at twisting little things here and there, throwing people off his scent. You had your work cut out for you.

MIDDLETON: Absolutely. Well, I was helped by the fact that the first book was so research-intensive, so I was used to throwing myself into a major research project. The thing about Karl is he gave a lot of interviews. That’s exciting, but it’s also a challenge. It was really interesting for me to start to see how his voice was there in the ’60s and the ’70s. There was this little quote he gave to an obscure French magazine in 1974, where Karl said, “What really matters is being open 24 hours a day. The world needs to be seen in terms of what can be made of it. Genius is knowing how to take ideas from everywhere, and I am the worst of vampires. I practice vampirism to the nth degree.” That’s something that he could have said in 2014. That’s Karl’s discourse right there. I think that it’s essential to see how Karl was viewed by the New York Times, by Women’s Wear Daily in the ’60s, the ’70s. When he joined Chanel in 1983, the decision was somewhat controversial; a German designer taking over a French house, people were horrified. But when you really look at how Karl was perceived in the ’60s and ’70s and the early ’80s, of course Chanel hired Karl. It’s obvious that he was the right designer for them. Looking at the way fashion critics covered Karl in a really important way to get a better sense of how his work was viewed in the moment. The other thing is interviewing people who were really close to him at all moments of his life, from Victoire [Doutreleau] the model who knew him starting in the 1950s, to Anita Briey, who worked at Chloe and then ran the studio at Lagerfeld. Or someone like Paloma Picasso, who knew him starting in the early ’70s. Sandy Brant, who knew him in the ’70s. Sometimes people who were just close to him for a certain period. Stella Tennant, who was a really close model from ’96 until Karl died; or Anna Wintour, who doesn’t even remember when she met Karl, but it was probably sometime in the ‘70s.

BLACKMON: Did you have any resistance from people saying, “Oh, I don’t want to talk about Karl, that’s too intimate. Or were people pretty happy to talk?

MIDDLETON: It’s natural if you’re close to a subject and you hear that someone wants to write a book about them, you ask, “Who is this person and what do they want to do?” It’s my responsibility to make the subject feel comfortable with the project. To be honest, I encountered resistance with Chanel. My contact [there] was chilly in our first meeting. It took a while for me to make it clear that I wanted to write a book that was serious. Since that time, Chanel has been incredibly helpful in granting access to documents in the archives, putting me in contact with executives at Chanel, including Virginie Viard, Bruno Pavlovsky, people who worked with Karl very closely for decades. Chanel Archives has even done a very thorough fact check of the manuscript, which I’m incredibly grateful for. There was no censor, they allowed me to write what I wanted to write, but they were very meticulous in terms of fact checking.

BLACKMON: You knew him professionally and personally. Strip away all the fabulousness, and what are your thoughts on Karl the man?

MIDDLETON: I tell that story in the book about how, after I’d got to know him, I was really struck by the clash between his public image and who he was in private. I said to him, “I’ve rarely seen someone who has a public image that’s so harsh and almost unpleasant, but then when you get to know them you find out that they’re so warm and amusing and actually moving.” And he said, “Well, it’s better that than the opposite, no?” So that was a thing that always struck me about Karl. He was a surprisingly warm, interested in other people, interesting person. I have been struck in the research in this project by how many people were moved to tears in their interviews. I would say probably a dozen people cried at some point in the interview, which doesn’t happen if you just think a person is “okay,” if you just kind of like someone. Karl was really beloved by so many different kinds of people, someone grand like Anna Wintour or Paloma Picasso, but also someone like his butler who worked with him for decades or Francois, who oversees Choupette. One day I was going for an interview at Chanel, and they had a little VIP salon in the couture salon, and there was this security guard downstairs and I explained that I was working on a book on Karl. He’s like, “I just loved him. He was just such an amazing man.” This is just someone who works the door there and who just volunteers that.

BLACKMON: If I can softly push back on that, there also seemed to be a more prickly side to him. I know that friendships don’t last forever, but if you look at Karl’s social topography, there are some bodies there. Ines de la Fressange, they had a famous row. There was Andre [Leon Talley], Yves [Saint Laurent], and Pierre Berge. He could really cut you quick, then move on and never look back. I’m wondering, did you ever see that side of him? Or do you think that, too, was part of the ruse?

MIDDLETON: One of the things that I say in the book is another quote from Karl about revenge, that he’s this person who pulls the chair out, and it could be 10 years after it happened.

BLACKMON: Yes, yes.

MIDDLETON: I think that Karl wanted to cultivate that image, because it keeps people on their toes. Watch out, or you too might be frozen out. There are examples of falling outs that he had, but there are a lot of examples of relationships that endured for decades. I love Andre and I think he was amazing and that The Chiffon Trenches was unfortunate. Because I think that there’s no one in the world who did more for Andre Leon Talley over the decades than Anna Wintour and Karl Lagerfeld, who were more generous to him, who were bigger supporters of his. His falling out with Karl isn’t quite as clear as he makes it. I’m not really sure that from Karl’s point of view there was a falling out. That was late in Karl’s life, it was right before he knew that he had cancer, but I don’t think that the split from Karl’s side was as dramatic as Andre felt that it was.

BLACKMON: Karl was one very astute commercial developer. The properties he did are almost an extension of his photography and designs. They’re pure works of art. I got so excited reading what you wrote about going to Villa Jako in Hamburg in the book. That’s my favorite property of his.

MIDDLETON: Well, it was extraordinary. That was the first time I’d ever traveled with Karl, seeing the whole entourage at Le Bourget, which is the private airport north of Paris, and then waiting for Karl. I’d waited for Karl a lot at that point, but it was the first time we’d waited on a trip. You’re at the airport and the cars are coming and his entourage is there and we’re all just waiting, and then we get on the Falcon 50 or whatever the plane is and we fly to Hamburg, and then the caravan to the house. Then going up in that neighborhood where Karl was born, that beautiful neighborhood of Hamburg. It’s a leafy hillside neighborhood that overlooks the river there, and then pulling into this house and then arriving. Karl is sitting there art directing everything. Bringing things in, seeing if it works. “No, that overwhelms things.” Banishing it back to the van. Being there was extraordinary. The house was extraordinary, and interviewing Karl about it, understanding what the references were, some of which I knew, many of which I didn’t, those kinds of Northern European references. Even the bathrooms by Andree Putman were just incredible.

BLACKMON: That house has always spoken to me. Going back to Karl the person, at some point in this working relationship that you have with him, you must have felt like you were on eggshells, though. The private jet, the homes that overlooked the Elbe River in Germany, going to the Schloss Hotel in Berlin, the shows.

MIDDLETON: No, no. In fact, I’m very conscious of two mistakes that I made with Karl. One was in the summer of 1998, I was taking some time in the south of France, when he had his place in Biarritz, and he said, “Oh, you should come over and see us at Biarritz.” He gave me his number and there was a plan that I would come for a few days at some point. I’m seeing friends over by Antibes and then it was time for me to organize my trip there and I just didn’t do it and I didn’t call Karl. Afterwards, he’s like, “Oh, what happened? You didn’t come.” But afterwards I was thinking, “Gosh, that was really bad form. Karl invited me to come to his place and not only did I not come, but I didn’t call to say that I wasn’t going to come.” That’s not very cool on my part. Then another thing, he gave me this amazing collection of men’s magazines called Adam from the ’20s and ‘30s He said, “But I want them back.” I never gave them back to him, I still have them here somewhere. So I feel like I should take them over to 7L, where Chanel owns the bookstore. But if Karl was really that harsh about things, he could have cut me out. But he didn’t. But I feel like I was disappointing in those two areas, and I didn’t really want to disappoint Karl.

BLACKMON: There was Chloe, Chanel, Fendi, then there was Lagerfeld Gallery, then it was Karl Lagerfeld, now it is its own iteration. I’ve been reading reviews for a long time, and it always seemed like the best reviews were always for Chanel Couture, Chanel pret-a-porter, and Fendi. His time at Chloe predates me. Whether it was subconscious or intentional, why do you think it seemed like his best work went to others? When it came to his own line, it was almost secondary if not tertiary.

MIDDLETON: First of all, Karl pioneered the role of freelance designer in the ’60s. After he left Patou, it was really the first time someone had begun a significant career as a freelance designer, not working for their own house, not starting their own house. He felt like that was modern, and I think that time has proven him correct. I think what we see now are a lot of freelance designers, even people that are working at a major house or have their own house, working with others as well. I think that it just happened that way. I agree, there was definitely a gap between the significance of Chanel, the significance of Chloe, and the significance of Lagerfeld. I know that a lot of people slide Karl off for that. “Oh, yeah. He never built his own house.” But he took a house that was almost bankrupt, Chanel, and turned it into an 11-billion-dollar company. He did something that no one had ever done before, which really shows how you could take a house that was nowhere and look at its history and make it fresh and exciting and modern. For me, whether it has his name on the door or not, it doesn’t alter the achievement.

BLACKMON: When he passed away, how did you find out? Where were you?

MIDDLETON: I was in New York. So I just heard like everyone else.

BLACKMON: When was the last time you were personally with him?

MIDDLETON: In Dallas. It was amazing, because it was so incongruent to see him in Texas. Starting in the ’90s when we would go to do these previews for Women’s Wear, I would see the first versions of some designs and Karl would tell me about what he wanted to do and I remember thinking from time to time, “Hmm, we’ll see how that works out.” I wasn’t always super enthusiastic. Then by the time the show came around and you saw what he did in terms of music and staging and the improvements that he’d made to the designs, you were like, “Oh, yeah. Now I see what he wanted to do.” I shouldn’t have doubted it, because it always came off. I think I had that feeling about Texas too, like, “Gosh, what is he going to do in Texas? He’s going to do it at the World’s Fair grounds?” Then you went there and it’s just extraordinary.

BLACKMON: Do you think he liked Dallas?

MIDDLETON: I think Karl liked wherever he was. He was super interested in everything that was around him. So yes, I do.

BLACKMON: Do you have an inkling of what your next book will be? Or are you still in Karl world?

MIDDLETON: There’s so much work to do when you are finishing a book like this. So I’ve not had much time to think of the next project. But the last book took a year between when it came out and when I was ready to do the next one. This might take a while.

BLACKMON: I’m sure the next one will be even better.

MIDDLETON: Well, the problem is Karl is such an exciting subject. It’s hard to top that.

BLACKMON: Well, thank you so much for your time. That was great.

MIDDLETON: Talk to you soon, Christopher.