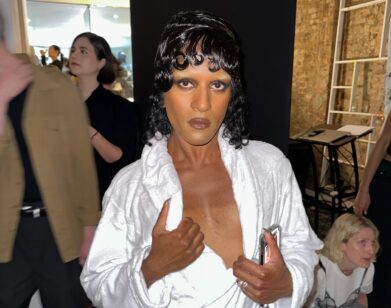

Rick Owens

I LIKE THE IDEA OF PROMOTING ALTERNATIVE IDEAS OF BEAUTY. THE FASHION WORLD CAN BE VERY STRICT ON THE STANDARDS OF BEAUTY, AND I LIKE PUSHING IT AROUND A LITTLE BIT. rick owens

When I think of an avant-garde, I picture an actual forward patrol—a pack of medieval knights or a lone, hooded scout gone on ahead of the main encampment, pioneers exposed to a rough frontier and unknown elements out there on the horizon, laying down an advance base and making a safe place for others who may follow in their footsteps. Maybe I’m too literal. Or maybe I have this picture because I so closely associate forward-thinking with Rick Owens that, in the nearly 20 years that I have known him, Owens has become, for me, a metonym for avant-garde-ness, filling the term with all of his slouchy Druid aesthetics and monkish ethics.

In life and work, Owens is so far out of the mainstream, ahead of the pack, that his regular dispatches from the fringe, in the form of semiannual fashion shows, can seem like transmissions from an (incredibly luxurious) alien civilization—and give us hope for the road ahead. This is not by chance—nothing is, in his obsessively edited world; not his clothes, not the furniture he designs, not his custom-made marble toilet. In his five-story mansion in Paris, formerly the headquarters of the French Socialist Party (where, before the furniture they made for the place had been installed, he and his wife, Michèle Lamy, camped out in the empty building, sleeping in improvised tents made of mink stoles), Owens lives a life of ascetic detachment, an Erasmus of the Left Bank, consciously protected by and enclosed in an adamantine regimen of work and exercise. He is both buttressed by his small circle of friends and collaborators, and insulated from the dumb-ass distractions of the world.

Whether it is an indulgence or privation, this monastic devotion seems to have come early and easily to him. Owens grew up in central California, in a dusty part of the world, and some of his earliest memories are of the muslin robes of the local nuns, dragging in the dirt behind them as they climbed the town hill. In the 1980s, after moving to Los Angeles, he worked in warehouses cutting patterns for companies knocking off luxury lines. In 1988, he met Michèle and worked with her on her brand, Lamy, before launching his own namesake line in 1994. When, in 2002, Owens was hired to breathe new life into the centuries-old furrier Revillon, he would sleep on the floor of the factory during production so as to better inspect every stitch of every garment, constantly editing, reworking, perfecting every piece as they came together. And if that sounds impossibly glamorous—a romantic reimagining of events to make a more mythic life story, that of a bohemian artist in a fashion-y garret—his world has only become more glamorously devotional, more La Bohème. At 54, Owens is even more of a monk (though with the passionate following of a revivalist or a cult leader)—both sober and decadent, suppressing the more lurid elements of his id and its appetites with a rigorous regimen in the pursuit of beauty. The way he has presently constructed it, his life is basically a scaffolding of steel will upholstered in sable fur.

But within that framework, be it protection or a prison, he seems to be getting more comfortable, more playful, allowing whimsy and voluptuousness to overwhelm the previous stricture of his forms. “Balancing control and collapse is what I’ve built my aesthetic on,” he wrote in the show notes to his Fall 2016 menswear show. “Discipline versus indulgence, immortality versus its defeat, architecture versus wilderness … I’ve been romanticizing straight lines for a while, but here they’re fractured and incomplete, letting an organic energy seep through.” In other words, rest in peace to the brutal elegance of Owens’s Art Deco period. He’s striking camp and heading out a little further, toward something more romantic. Welcome to his Art Nouveau period.

In mid-February, I dropped in on a call between Owens and one of his early heroes, a fashion rock star of the ’80s and ’90s, Claude Montana, to hear the two designers’ thoughts about fame and fortune, about sex and power, and wearing clothing as armor. —Chris Wallace

CLAUDE MONTANA: Rick, I went to your store this afternoon. I tried on some menswear, which looked very nice actually. I wanted to congratulate you for all of the beautiful work that you’ve done.

RICK OWENS: Oh, I’m thrilled.

MONTANA: You don’t have to be thrilled. I’m just telling the truth.

OWENS: Oh, well, coming from you, that’s extra-special. I’ve been such a fan of yours. I was just thinking today about your work at Lanvin. There aren’t enough images of those pieces around.

MONTANA: You can’t find them on the internet?

CHRIS WALLACE: They are few and far between.

OWENS: Because documentation then was so different. The way that people took pictures and distributed them was different. I hope enough of it is in museums.

MONTANA: Most of those pieces are at the museums.

OWENS: You were never sentimental about keeping your own archives?

MONTANA: No.

OWENS: [laughs] I love that. I’ve been pretty bad about it myself. I don’t save very much.

WALLACE: Claude, I watched a video recently in which you were talking a lot about your love of film. Do you have a favorite?

MONTANA: I used to be very fond of an old movie from the ’50s called Auntie Mame [1958], by Morton DaCosta with Rosalind Russell. The clothes are done by Orry-Kelly. They’re wonderful.

OWENS: Did you ever see Travels With My Aunt [1972], starring Maggie Smith?

MONTANA: No.

OWENS: That’s a pretty good one. It reminds me a lot of Auntie Mame. You know what I am watching now almost every morning? I am watching Cleopatra [1934] with Claudette Colbert. The production values are so beautiful. Chris, last time I spoke to you I think I was talking about Cleopatra, and I am still watching it.

WALLACE: What is it about it that keeps you coming back?

OWENS: There are so many layers—the quality, the sumptuousness. Also I think it is that whole Art Deco aesthetic, and it’s all black and white, so. There’s just a depth of field in the framing and the staging and the scale of everything. I am still impressed. There is also a new version of Metropolis [1927] on YouTube where the definition is so clear. Do you remember Metropolis, Claude?

MONTANA: Oh, yes.

OWENS: I can imagine you relating to that movie very much. Your clothes look like they belong in those sets.

WALLACE: I’m always surprised you’ve never turned your hand to creating a world, whether it’s a movie or something for the stage.

OWENS: It’s just not something that ever appealed to me. You know why? I realized because you can’t control the people enough. That’s the problem with opera. Opera singers can have fantastic voices, but you can’t manipulate them as well as you can a drawing or a painting. There’s too much left to human chance. Does that sound too controlling?

WALLACE: You do certainly put on a show, though. I know that wasn’t your favorite thing to do initially, but you seem to really love it now. Claude, you’ve really enjoyed the sort of theatrical element of the shows, did you not?

MONTANA: I used to like that very much, yeah. But I’ve never seen a show of Rick’s.

OWENS: You have to come. I’ll make sure that somebody picks you up. I do love shows now. I realize that it doesn’t even have to be about clothes anymore. Especially women’s runway, because the way that women’s runway clothes get in the store … You know, there’s this whole conversation about what they call a show now.

WALLACE: Like what Tom Ford is doing? Timing the show to the collection’s release in stores—making it shoppable, basically?

OWENS: Right. Shop it off the runway. I am sure that there is something logical there, but I wonder if there’s an alternative to that, because there is something about being too desperate to please. I think this is a fast-fashion thing that H&M and all of those people already kind of rule, and they do it so wonderfully. I don’t know if we need to compete with that. Maybe we need to become even slower and less available, which is kind of ironic coming from me, selling stuff all over the internet. It sounds a little hypocritical coming from me, but I don’t know if I want stuff to be accessible right away, because then that makes it just too disposable.

WALLACE: I think that both of you have created these places that, whether by luxury or by sort of avant-garde-ness, exist outside of what the rest of the world is doing and draw people to them. Claude, did you feel like you were avant-garde? Did you feel like you were in a special realm?

MONTANA: I never thought that about my own work, no. But other people probably thought that about me.

OWENS: Yeah. I am not really engaged in the fashion world where advertising and a lot of editorial is essential. I suppose I could have engaged more personally, but I just never did. It kind of worked out for the best because any kind of success doesn’t really hinge on me being that visible. Like, I don’t have to actually be there when a store opens. I don’t have to present my collections to editors and buyers and explain it to anybody, so that’s kind of great. It either engages you or it doesn’t. There’s nothing I can argue that is going to convince anybody even more.

WALLACE: Well, that breeds a very passionate following. I don’t think that people sip Rick Owens—do you know what I mean?

OWENS: I think when you create a niche like that, it becomes so specific that people identify with it. People who like it, really like it, and people who don’t like it, really hate it. It’s polarizing in that way.

MONTANA: I don’t need somebody to like it. If they don’t like it, that’s all.

OWENS: Yeah, and that’s great, because it makes you very special to some people. It’s kind of like making yourself indispensable. If you really focus and apply yourself, you create something that’s … Did I just call myself indispensable? That’s kind of what I wanted to do.

WALLACE: I think that’s allowed.

OWENS: Yeah, but probably not encouraged.

WALLACE: [laughs] But I think that you’ve made a safe place where people can understand themselves better-better self-identify.

OWENS: The irony about making a safe space for certain people is that it creates a wall for other people. No matter how inclusive you want to be, the more inclusive you are, you kind of create something exclusive. It’s kind of funny how that turned out. I don’t worry about it too much, though, because it’s a natural evolution, and it will all even out. The funny thing is that the further it goes, the people who felt included are going to feel like it’s too general and will reject it at some point, and so you kind of run the risk of, like, a love affair that peters out. I kind of assume that that is inevitable.

WALLACE: Do you really?

OWENS: I am pretty skeptical.

WALLACE: I teased you recently that you’re softening from your signature sort of brutalism toward something more Art Nouveau. Is this a kind of blossoming? Are you letting your guard down?

OWENS: Well, it seems like that. All evidence points that way. Although, this week we were doing some jackets, these draped jackets, and, for some reason, we weren’t getting these drapes just right. For two days we were working on these jackets, and I was questioning everything, questioning my very existence: “I thought I knew what I was doing.” Like, “Why can’t I control this?” I was getting very, very uptight, which is the opposite of the serenity that I am trying to get to, the opposite of the serenity that I am trying to express. I was getting snippy with everyone. I was getting sharp and irritated and impatient and hurt. I was kind of horrified. I thought I had grown beyond this and reached a level of imperturbability where I could just sort of smile through some small inconvenience like this. I was a little ashamed of myself. I was just in a really bad mood about not being able to get these things done. I was thinking I have a problem communicating and getting my point across. I can’t engage with people. I can’t motivate people. I can’t move something forward in a positive, loving way. Why am I getting angry with people who really want to help? It will only make this worse. What is so threatening to me that it makes me negative? I know there is this petty side that everybody has, and I know that I have it, and I hate it, but I spend a lot of time forgiving myself for it too. So what? Everyone has their moments. But it threw me how not being able to get through to my team and not being able to express myself made me question how I operate in the world and how I communicate in the world. It was humbling.

WALLACE: Do you think about where that comes from? The rigor, the perfectionism …

OWENS: The impatience comes from insecurity, right? That’s what it would be. Because a perfectly serene person does not get flustered. I was flustered. And that flustered me—the fact that I got flustered. It irritated me. And I was already irritated. It was a weird-ass week. I was a total cunt.

WALLACE: Claude, are you a perfectionist?

MONTANA: I used to be. When you’re in front of a piece of clothing, if you do not exactly do what you wish you could, you won’t accept it. It’s making something that just corresponds to your own personality, to what you really wish.

OWENS: There are a couple of separate things, though, about expressing my personal idea of beauty, and also what could be considered beautiful. I like the idea of promoting alternative ideas of beauty. The fashion world can be very strict on the standards of beauty, and I like pushing it around a little bit. I like teasing those ideas a little bit, by promoting quieter kinds of beauty. But also I am thinking about beautiful aspirations and beautiful behavior, and I have found that now, with the fashion shows, I am able to express that a little bit more than I used to. So now I can introduce ideas of, like, “What if we lived in a world without shame?”—when I have guys with their dicks out. Or, with women carrying each other, it’s taking a minute to appreciate those moments when someone is supporting somebody in need. That’s a very stirring moment that we can all appreciate as a beautiful thing. That’s been exciting to me, that I’ve been able to do that kind of thing, promote those ideas.

WALLACE: I think it matters, because, in 10 or 20 years or so, people might have a different set of standards, because you will have expanded their language, their reference points, their empathy. But those things are elastic. They do come back in eras when things are more conservative.

MONTANA: It does come back.

OWENS: When I look at the runway now, they’re very referential to Mary Tyler Moore or to a kind of a ’70s thing. Which shocks me, because Claude’s clothes were not referencing anything before. They were modern and architectural, and they seemed right for the time. And clothes now, they’re all kind of nostalgic. I don’t know what that’s about. I don’t get it. Oh God, I am sounding really critical aren’t I?

WALLACE: Claude, do you notice references to your work in clothes that people are making today?

MONTANA: People are telling me so, but I don’t get that.

OWENS: Are you familiar with the designers collaborating with H&M? Would you have ever done that?

MONTANA: Yes, of course. Why not? That would be a great experience actually. Why not be accessible to all kinds of women? It’s a great idea. Nobody ever came to me and asked me to work for a company like that. But, as you say, Rick, if you make yourself too available …

OWENS: It dilutes it.

WALLACE: But, Claude, it seems as though you didn’t ever have a problem with exposure, personally or professionally? Did you mind being famous?

MONTANA: Well, actually, I guess I did mind being famous. But then, in another way, being anonymous isn’t really great.

WALLACE: Rick, do you struggle at all with that?

OWENS: Well, I never really had the fame that Claude did. I live so quietly; there is no fame here. But I do have to say, though, that it’s lovely to walk out the door, and every once in a while, somebody comes up and says something nice to you. I have enough fame for people to be friendly on the street. It’s lovely to feel connected in the world. I feel like I kind of engaged with the world, and they’re kind of feeling the same thing.

WALLACE: It doesn’t seem like that’s the main point, though; it feels like a by-product. Would you be making clothes in a garage even if nobody knew about it?

OWENS: Yeah, I really would. That was my business plan in the beginning. That’s exactly what I was going to do. I was going to make clothes and be poor and just do what I wanted. I mean, I am sure I would have been frustrated every once in a while, but the plan was to do exactly what I wanted and not to have to compromise.

WALLACE: Was there a sort of image in your head? Had somebody done that already?

OWENS: Oh, yeah. There was Charles James. Then there was Iggy Pop and Patti Smith—people who just did it their own way.

MONTANA: I was very fascinated by the designers who made clothes for the movies, like Adrian—he did fabulous things—and Travis Banton.

OWENS: Did you ever spend time in Los Angeles?

MONTANA: Yes, I went to L.A. I met with Edith Head. It was quite a while ago. She was very funny. And you know she had, like, seven or eight Oscars. And she used to put the Oscars in front of the mirror, so when the people would come into the room, they would see seven but then multiplied by the mirror to, like, 50. [laughs]

WALLACE: Claude, you were once called the Marilyn Monroe of the gay world.

MONTANA: [laughs] That’s funny to me. I don’t know. If you say so.

WALLACE: You were a sex symbol.

MONTANA: No! Maybe.

WALLACE: Was sex appeal or sexuality important to you in your work?

MONTANA: Well, it was very important at some point in my life, but not anymore. Not today. It’s not important anymore.

OWENS: It was never overt sexuality, though. It was never corny sexuality. There wasn’t a lot of boobs; it was very covered up. I remember your clothes being severe and covered up. It’s more about power.

MONTANA: That’s for sure.

WALLACE: If Claude is Marilyn Monroe, Rick, would you be Garbo?

OWENS: I want to be Cher.

MONTANA: I would rather be Garbo than Marilyn actually.

OWENS: I remember Cher went with you to the French fashion awards. She looked incredible.

MONTANA: She came from Los Angeles to be with me at the awards.

WALLACE: Was Cher something of a muse for you?

MONTANA: She was … something. I think muses are important. You’ve got to have muses. Maybe a few of them.

OWENS: I have a beautiful team who are very influential in what I do. It’s kind of funny how everybody’s energy combined creates something beyond what there would be with just me. I mean, obviously. There is kind of a great family balance when you have the right group of people around you that I think is very powerful. That’s an amazing thing, to be able to harness the power of a group of people. I mean, you’re living with these people in a submarine, in a fashion submarine, so many hours a day, sweating towards the same thing. There’s got to be some amazing alchemy there that, if the combination were different, wouldn’t quite be the same.

WALLACE: So what is your hiring process like, because you’re inviting somebody into that? You must have rigorous background checks.

OWENS: [laughs] You would think so. But I am incredibly sloppy about it. I would just say no to everybody. So it’s Michèle and my CEO, Elsa, who are kind of the gatekeepers. It doesn’t always work out. Sometimes I really can’t make it work–there’s never anything really forceful, but the people who don’t work just kind of fall away gently.

WALLACE: Both of you have these sort of tribes. But, Rick, who is in your community? Who are your close friends?

OWENS: It’s probably my family, the family that I’ve created here. I am with them every day. It’s just how it becomes. But I was just thinking, I don’t know designers that really hang out together. I really care for Raf a lot. And I just met Phoebe Philo, who is just adorable. Alber is just lovable. There is a great group to know. It’s a lovely period, a nice generation of people that are doing stuff.

WALLACE: Are you looking at shows online?

OWENS: Oh yeah. I look at everybody’s shows because I am a fashion fan. I mean, I like fashion. And I like to see what everybody is doing, and it’s fun. Sure! I look at everybody and observe everything.

WALLACE: Don’t you also go deep on Tumblr?

OWENS: Oh yeah, I do. Totally. For a while there, there were some super-disturbing ones. Very, very dark and very sick, and I was enjoying those for a long time, but then I don’t know if I just wandered away from that or if it just kind of went away, as if the novelty ran out. They’re not as creepy as they used to be.

WALLACE: Creepy how? Like, snuff?

OWENS: Well, kind of going there. Nothing illegal, but just kind of sinister, creepy stuff. It was fun because it was lurid. There is a big lurid side to me. To all of us. I mean, nobody can deny that that’s a little bit titillating and exciting. It’s only human.

WALLACE: I’ve always been curious about that sort of walking on the wild side part of your life, maybe because I am so square. Did you walk on the wild side, Claude?

MONTANA: I used to, taking drugs and stuff like that. It doesn’t interest me anymore.

WALLACE: Did I read that you used to like sex clubs?

MONTANA: Oh no, no, no.

OWENS: Chris, there are no sex clubs in Paris.

WALLACE: Ruin my fantasies, why don’t you.

OWENS: [laughs] There are none!

MONTANA: On top of that, it was very dangerous with the disease going around.

WALLACE: Right. Sex was very scary.

OWENS: I am thinking that the clothes that you were making during that threatening sexual period were very much about being powerful and being protected.

WALLACE: Like armor.

MONTANA: Probably. They were like protection, maybe.

WALLACE: Rick, do you feel like your clothes are armor at all? I feel like your clothes are very open and embracing of late.

OWENS: They have been armor for sure. But armor is just a good-looking thing. There’s also my theory about men in military uniforms: Military uniforms have just been perfected over centuries to make a man look dignified and heroic. And I think those are important qualities to everybody. Everybody would like to project a sense of strength and honor, so clothes as armor don’t necessarily just have to mean defense; they can also mean something a little bit more elegant. But it’s true, my clothes have become very sensual of late, and I don’t really know what that means. I don’t know if, 10 years from now, I’ll be able to figure out exactly what the motivation was. Maybe it’s me just softening with age. But as with the draped jackets, I thought I was softening, and then I wasn’t. I was just still uptight. It just goes to show that there is always room for learning. I was surprised by how far away I was from that level of serenity that I am kind of hoping for at some point.

WALLACE: But you’re so self-reflective. And I don’t mean neurotic or anything, but I don’t think you’ll ever totally let yourself off the hook.

OWENS: You’re right. I’ll never let myself off the hook because I am also incredibly critical about everything. I am always going to be beating myself up and then forgiving myself afterwards for beating myself up, and then getting on myself for letting myself beat myself up … I’m very busy. Very, very busy.

WALLACE: But the critical-ness. How do you know when you’re right?

MONTANA: You never know.

OWENS: I don’t always know exactly what’s right, but I know what’s wrong a lot. I can usually define that. I collect enough stuff all day long so that I feel like I kind of have a library of ideas that I can edit, and I can create new compositions. The part where I am supercritical is my behavior, how I can put the right kind of energy out and how I can leave a trail of love behind me instead of making somebody feel like shit because they couldn’t get something done that I wanted. I hate that. I know when something is wrong if it didn’t come out in a positive way. I am not as critical about the stuff that I make as you would think. I have learned at this point how to get it to where I want to be pretty much. That’s why, with these jackets, where I wasn’t getting it, it was freaking me out … Oh, by the way, everything worked out today, and I love everything, so the mood is over.

WALLACE: [laughs] Oh good. Well, that’s all it takes.

OWENS: Yeah, really. I forgot to tell you that part.

WALLACE: I wonder if your sort of regime is a protection from behavior that will lead you to more self-criticism.

OWENS: Oh definitely. It’s just about behavior. Yeah, regime … I never work out enough, etcetera. So it’s definitely a barrier from letting my head get carried away with me.

WALLACE: Don’t think I don’t notice that you didn’t answer that question about lurid, wild side…

OWENS: I’m saving that for the book.

WALLACE: I really want you to write an autobiography.

OWENS: Well, you write it. But I’m not going to give you that information until later.

CLAUDE MONTANA IS A FRENCH FASHION DESIGNER. CHRIS WALLACE IS INTERVIEW‘S SENIOR EDITOR.