The Womenswear Designer

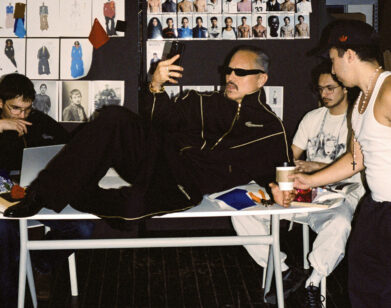

ABOVE: PHOEBE ENGLISH IN LONDON, NOVEMBER 2015. PHOTOS: MARK RABADAN. STYLING: FANNIE SCHIAVONI. MODEL: INGA DEZHINA/STORM MODEL MANAGEMENT. HAIR: LARRY KING/STREETERS LONDON. MAKEUP: JAMES MOLLOY/D AND V MANAGEMENT. MANICURE: ADELE SANDERSON USING SOIGNÉ.

As a teenager growing up in Warwickshire, England, Phoebe English dreamed of being an actress. “I applied to loads of drama schools and I didn’t get in anywhere,” she recalls over the phone. To fill the time before she could reapply, English enrolled in an art foundation course. Something stuck, and she found herself studying fashion design at Central Saint Martins. Ten-odd years and two degrees later, English is one of CSM’s most promising graduates with a four-year-old eponymous label produced entirely in the UK and sold at the likes of Dover Street Market (New York, London, and Ginza) and H.Lorenzo (Los Angeles). Though she began exclusively designing womenswear, English recently expanded her label to include menswear as well.

“It was never my goal to have my own business or have my own label. I’m not one of those people who wants to be the god of fashion and be amazing and take over the world,” the British designer explains. “I just want to enjoy making nice things, and it happened that to make nice things goes along with doing a fashion label.”

“There are parts of fashion that I feel quite separate from sometimes,” she continues. “Not in a bad way. I’m just pottering along my own path.”

Styled into looks, English’s clothes seem intricate and romantic, but each look is anchored by a series of staples. “The most common misconception with my work is that people don’t realize that there may be six or seven garments in one look, and actually some of them are really simple t-shirts or really simple shorts that are very easy to wear,” she notes. “When you see the collection in the showroom, it’s such a different experience because all of those looks are broken down into these individual components.”

EMMA BROWN: I know you grew up in quite a creative family, but was anyone else interested in fashion?

PHOEBE ENGLISH: Definitely. It wasn’t a house of couture or anything, [but] it was a very creative house and there were amazing clothes everywhere—kimonos and hats and quite bonkers things. It wasn’t a very conventional household to grow up in.

BROWN: When did you decide that you wanted to be a designer?

ENGLISH: It wasn’t really a decision. It was an accident. When I graduated, I didn’t know what to do. I did a small collection, Dover Street bought it, and I ended up having a label. It wasn’t a grand idea. It was accidents that happened because something else didn’t happen. There are lots of people who go to Saint Martins because they want to have their own label, and that’s why they’re there, but I was there as someone who was exploring possibilities and enjoying the moment and being on a journey. Then it just ended up here.

BROWN: Did other students at Saint Martins look down on you because you didn’t have the same goals as them?

ENGLISH: I had a weird time at Saint Martins. It was the best time of my life and my whole world is full of amazing friends that I made there, but I was so shy and so self-conscious, I really didn’t feel like I was qualified to be there. I was very, very embarrassed about my work. Just showing a tutor my work was absolutely mortifying. [Even] when I started my own label, I was shy of my work. I could never wear it. It’s taken me a long time to feel that I deserve to be doing what I’m doing. As I’ve gone along, I’ve learnt to just enjoy it a little more and not be so anxious about it all the time. But I don’t think they looked down at me at all. It’s a very competitive atmosphere to grow up in, because you do grow up in that environment—I started when I was 19 or 20 and I finished when I was 25 because I did a four-year BA and a two-year MA—and you change quite a lot in that time. [But] it’s really an education that’s about the individual, and everyone is encouraged to work in their own unique way. There’s not a particular way of working that’s inflicted upon you or expected of you. So I think as we all settled into our own ways of working, it became a bit less competitive and intense and neurotic and it got more into the pace of things.

BROWN: I heard that you worked in Paris when you were 18 for a couturier. Is that true?

ENGLISH: Yes, I did. I worked for a corsettier called Mr. Pearl, who makes made-to-measure corsets for private clients and also did all the Thierry Mugler corsets in the ’80s. He’s worked with Jean Paul Gaultier and John Galliano. He makes all the corsets for Vivienne Westwood. He is an extraordinary person and it was a really magical time. I’d never been to Paris before. My aunt took me over and found me somewhere to stay. I was beading every day—I was doing hours and hours of really intense hand-beading and couture embroidery with him. That’s where I learnt everything, to be honest. He explained the whole fashion world to me. I was sat there beading pieces next to a dress hanging on the wall that was waiting to go off to Isabella Blow. It was amazing to be completely submerged into that world that I’d read so much about. Then, of course, I went back to London to start Saint Martins and it was just a totally different experience. It was a bit of shock to start from a Paris perspective and go to a really grimy, edgy, London environment.

BROWN: When you graduated from the Masters program, what made you decide to do a small collection?

ENGLISH: I won a few prizes, which wasn’t what I was expecting at all. I’m still really shocked about it even now. As I said before, I wasn’t studying it in order to win prizes or make people know who I was. I was just doing it because I liked to do it and I very naively hadn’t thought at all about what that meant or where it could go or what I should be doing. So then I was really shaken off kilter. I was really overwhelmed by the response the collection got—going from getting one email every two months to getting 10 a day—and I didn’t know how to cope with that and press requests and interview requests and people ringing you and contacting you. When you’re on that [CSM] course, it’s a very monastic existence, so it was a bit of shock to have all of these exterior people trying to come into your life. I was kind of hibernating, trying to process what was happening and figure out what I should do. I’d been in education since I was three, and I was finally out for the first time in all those years. I got a call from an organization called Fashion Scout and they asked me if I’d like to do a collection. I didn’t return their calls. They called me again and again, and I didn’t pick up the calls. Then I picked up the phone by accident because I thought it was my friend and they somehow persuaded me to do a collection. The idea was to do a really small body of work as quietly and privately as possible because I didn’t have anything else to do. I’d gone for a few job interviews, but I didn’t really want a job. Then Dover Street Market bought the collection, so my plan didn’t really pan out. I registered my company after that.

BROWN: Did you pick up the phone when Dover Street Market called?

ENGLISH: By then I was working with someone that did pick up the phone, so I was quite lucky. I’m still not very good at picking up the phone. I made some private commissions, and one of the girls I made a private commission with wanted to work with me. We made a little team, and [that way] I had the business side covered, because that’s the side that I’m not very good at —or wasn’t very good at—and she comes from a buyer’s background, so she had much more knowledge of the commerce of fashion. She picked up the phone.

BROWN: I read that you start each collection with a fabric. Has that always been the case?

ENGLISH: That’s always been the case and that’s because I come from a knitwear background. I studied knitwear with fashion, so textiles and the surface have always been the key element of my work. Some people spend 14 hours in the library and then they spend 75 hours drawing on their sketch pads and that’s how they work, whereas I prefer to build things with my hands. It’s definitely more of a material- and instinct-led design process than a referential design process. Each collection is autobiographical, so each collection is a response to what’s happening to me at that time, how I feel, and what materials I feel represent that or which materials I’m drawn to emotionally. It’s more of a personal thing than referencing images.

BROWN: I feel like most of the time when you go to a fashion show and read the show notes, they always say something along the lines of, “The designer was inspired by this one particular Klimt painting.”

ENGLISH: Yes, I can’t stand that. [laughs] It drives me mad. It’s really hard to write the press releases [for my shows]. We try and make it explanatory, because obviously it has to be something that people can understand, but it’s an absolute battle and I always leave it right till the last minute and then it’s always a disaster because we’re trying to do it in a rush. I work quite a lot from words or things that I write in my book, so once season we tried just using the designer’s notes as the press release, but it didn’t go down very well. It’s still a work in progress. We’ve been going for four years; eventually I’m going to find a good way of doing it.

BROWN: I saw a picture you posted of a piece of woven shredded silk on Instagram. What’s that from?

ENGLISH: That is a bit of production that’s come in. All of the textiles are handmade. I used to make them all myself, but now that we’re a bit bigger it’s hard for me to make them all myself, so we’re working with a few different freelancers. That just came in this morning ready to be made into some production to ship out before Christmas. I’m really interested with the ebb and flow of how the studio works, and how the landscape of the studio changes in different times of the year—it can suddenly be covered in red velvet or shredded silk or there might be flax everywhere. It changes every day. It’s quite nice to have Instagram because it’s a good vehicle to capture or document those ephemeral moments that are passing through your daily work.

BROWN: How did you find the freelancers who make your materials? I imagine it must be quite hard to find someone who is both talented enough and willing to work on the same scale as you.

ENGLISH: I never tried to find any manufacturing for any of the textiles I do, because it’s so labor-intensive and it’s really complicated and it’s not something that you can just send to an embroidery factory. The textiles that I do I’ve started to call constructed textiles, which is when you have to physically make all of the surfaces like you would do with knitwear. It was my way of reinterpreting knitwear—I got bored of knitting quite quickly, and this was my way of continuing to explore that working ethos. It is tricky, but now we only work with people who have interned with us who are now graduates. They’ve become freelancers in their own right and they know the process intimately and have grown up with it. We’re a made-in-England brand and that’s something that was very important to me from the start. We work with London-based factories for all the cut-and-sew based pieces and then London-based freelancers for all the textiles.

BROWN: Was the made-in-England aspect important to you conceptually because you wanted it to feel like a very English brand, or was it more about humanitarian and ethical concerns?

ENGLISH: Some people think it’s because of my name, but it’s absolutely not. It’s probably because I worked in New York as an intern. I loved my time there very much, but I did find it very confusing because I’d make the stuff to make into a garment, and then we’d put all of these things into an envelope and we’d send the envelope away to the other side of the planet. We’d wait for ages and ages and it would come back from the other side of the planet, and it would be wrong and it would have to be sent back again. To me, this did not seem like a logical way to make fashion. It felt not in the moment, and it felt really inefficient [in terms of] the time use and the energy use—putting things on airplanes, taking things off airplanes. I felt it could be done much quicker if you were just doing it right in front of you in the same city. So now that I have the opportunity to run my own production, that’s how I run it. I want things close by. I don’t want things on airplanes wasting loads of fossil fuel. It’s a bit about ecology and a bit about time, but I find flying things to the other side of the planet to get made a really strange concept.

BROWN: Is that something that you’re worried about at all for the future? I imagine when you’re successful people are always pushing you to expand and you can only grow so much if you want to keep everything based in London.

ENGLISH: I am worried about it, but at the same time I’m quite stubborn and if I don’t want to do something then I won’t do it. I think within fashion there is so much pressure and so much external need for more things, more things, more things, and that’s definitely a subject that people are talking about. Do we need all this stuff all the time? Can designers continue to actually physically make new things again and again and again with no thinking time in-between? I’m quite conscious to try and keep a really sustainable level of work for myself. I don’t do 34-look collections, because I don’t have a production team that could manage a 34-look collection. I do a 17-look collection because that’s how big my team is. So I’m very conscious about workload and speed and I try and keep it within a reasonable amount. I’m not a “more is more” person, I’m a “that’s enough” person.

BROWN: Do you wear your own designs now?

ENGLISH: It took me a really long time. I used to have to be really persuaded into them. I found it a really bizarre experience having yourself on yourself. It felt like boasting in a way and really attention-grabbing. Now I’m a bit more relaxed, but it is really hard to enjoy because you’re constantly critical of it all the time. There are pieces that I wear all the time, but the more complex things that are a bit ostentatious I still struggle with because I don’t really like people to look at me.

BROWN: Have you ever come across someone you don’t know wearing one of your pieces?

ENGLISH: Yes! I have. It’s really exciting. It’s like Christmas. It really makes you smile. I’m actually grinning quite a lot just thinking about it happening. It’s very humbling and flattering when people take their money that they’ve spent all month earning and they choose to spend that money on something that you’ve made. I haven’t stopped feeling amazed by it.

FOR MORE ON PHOEBE ENGLISH, VISIT HER WEBSITE.

For more from our 16 Faces of 2016, click here.