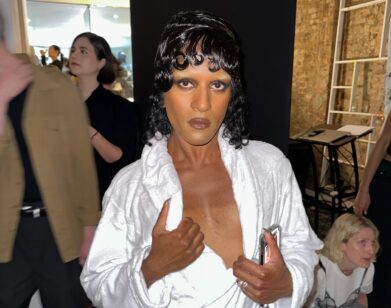

Peter Philips

To call Peter Philips simply a “makeup artist” minimizes the legacy of the visionary image-maker. Since his career took off in the late ’90s, he has redefined notions of beauty, on camera and on the catwalk. Those silver reflective eyeliner stickers that gave the models at Dior’s fall/winter ’14 couture show a superhuman, extraterrestrial élan? Dreamt up by Philips. The sooty, painted-on watercolor eyes at Dries Van Noten’s fall ’16 outing? The dusty, up-to-the-brow-bone bronzed lids and subdued peach mouths at Dior’s Resort 2017 show at Oxfordshire’s Blenheim Palace this past June? Julia Nobis’s dark, gothic lips for the maison’s fall 2016 ad campaign? Philips, Philips, Philips.

A native of the Belgian port city of Antwerp, Philips, 49, first became interested in makeup when he was studying fashion design at the prestigious Royal Academy Antwerp. While working backstage as a dresser during Paris Fashion Week, he became fascinated with transformative processes of makeup and decided to pursue it as a career after graduating in 1993. Along with cohorts Willy Vanderperre, Olivier Rizzo, and Raf Simons, Philips rounded out a new guard of Belgians in fashion. Soon he was painting faces for the runways of Giorgio Armani, Alexander McQueen, and Karl Lagerfeld, and collaborating on iconic shoots with Irving Penn, Craig McDean, Steven Klein, and Inez and Vinoodh.

A particular breakthrough moment for Philips was on a 2005 Vogue shoot in which Penn used a Mickey Mouse mask Philips fashioned out of black lace for model Lisa Cant. Chanel soon came calling, bringing Philips onboard as its creative director for makeup, where he served from 2008 to 2013, generating wait-list-inciting palettes and nail polish shades. And in 2014, Philips joined the house of Dior as the creative and image director of Christian Dior Makeup, not just conceptualizing makeup looks for its runway shows and myriad ad campaigns, but developing the products themselves. It’s a billion-dollar business, which takes Philips all over the globe and commands four collections from him a year. (His latest feat: a new collection of Rouge Dior lipsticks, which ups the ante with a palette that includes shades of gray, fuchsia, and cobalt.)

To hear Philips tell it, the core of his artistry is a game of seduction. This past spring, his friend Natalie Portman sat down with him at a suite at Le Bristol hotel in Paris, the city where he now lives, to hear all about it.

NATALIE PORTMAN: We’re very serious now. Tell me about when you started being interested in makeup.

PETER PHILIPS: I always loved watching my mom do her makeup. Also, my grandma. Still, when I work on shoots and I smell Elnett hairspray, it reminds me of my grandmother. My mom used to do her makeup every day, really quick, not much, but she made herself look really beautiful. I was very much intrigued by all that as a kid. I loved to touch the products. But also my grandmother used to make clothing. I used to be involved, sitting next to her.

PORTMAN: Well, you studied fashion design.

PHILIPS: I kind of got interested in fashion and makeup because of the women in my family, but also, my father is a painter. My parents got divorced when I was 4, so I got to see my father on the weekends. I came into that world of paint and the smell of paint.

PORTMAN: Did you paint?

PHILIPS: I went to art school. Creatively, what I do now is a bit of both worlds. I create makeup and I create looks, but at the same time, it’s also practical things. I create foundations and lipsticks—practical products that you really need. It’s not just creative.

PORTMAN: Right. What you can fit into your purse or your pocket.

PHILIPS: The great thing was that my parents gave me a chance, probably with my father being a painter, of going to school to do creative things. I wasn’t allowed to go to fashion school straight away.

PORTMAN: Why?

PHILIPS: They said, “Fashion school?” It was the ’80s. “What can you do with fashion school?” They said, “Okay, you can do something creative, but in art direction.” It was a compromise between art and commerce. Then, when I got my degree in graphic design, I went to the Academy in Antwerp.

PORTMAN: How does the background in graphic design help?

PHILIPS: It was before computers. I went to school in Brussels, and we did everything by hand. We did silk-screening. You learn also about the different textures of paint and blending colors and mixing. We did photography, so we developed our own pictures, but we also had to do set design and learn about light, which are still things that I use now when I do shoots.

PORTMAN: It seems to be such a Belgian sensibility, also all the great people that you went to school with. You guys were a real movement.

PHILIPS: It’s funny because you don’t really realize it when you’re there, but when I went to the academy, the Antwerp Six had just become famous: Dries Van Noten and Ann Demeulemeester and Martin Margiela. They just started doing their shows in Paris as a group.

PORTMAN: What do you think it is about the culture or the light? What is it there?

PHILIPS: I think it’s a bit of everything. The fact, also, that there’s not much happening in Belgium. There’s a big culture and a big history, but it’s not a metropolis like Paris or London or New York. You have a group of young creative people who want to do something. They know they have to get out, because it’s not happening there. We’ve been conquered over the centuries. We’ve been part of Holland, part of France, part of Austria … So in our culture there is a mentality that you have to adapt. I used to live in New York. Now I live in Paris. I can easily adapt myself to two different countries and two different cultures. I think that helps a lot if you have to work with teams and for different companies and different photographers and different magazines. You try to fit in and be a part of the team. It was a big thing for me, being a part of the team when I do shoots. It’s not just me; when I create products, there’s a whole team behind me. You have to be …

PORTMAN: Not be too rigid.

PHILIPS: Yeah. I think that has to do with the Flemish culture. There’re a lot of influences from everywhere, and you can feel it. I am from Antwerp, and when you walk through the streets, there’s something from when the Spanish were there and something from when the Dutch were there, and you can see it in the architecture, in the paintings, and in the churches.

PORTMAN: What was different when you moved to Paris?

PHILIPS: I came here first as a fashion student. We’d help backstage. We were just footmen, kind of. We ironed; we helped dress the models … No budget. We all rented a room. We had no money. We faked invitations to go to see all the shows. It was always an adventure, and then afterwards I came as a makeup artist to do a show.

PORTMAN: When did you change from fashion design to makeup?

PHILIPS: I knew when I was in my last year at the academy. I didn’t have this passion for designing clothing like my fellow students, but I knew I wanted to do something in fashion. By doing the shows, I discovered the backstage, and I discovered hair and makeup were having all the fun. You’d see the models come in, and then suddenly they’d come back completely transformed, and they totally reflected the vision of the designer. I was at a Dries Van Noten show, and the models went in with their own style, and within an hour, they were transformed into how Dries saw these women. Next day, same girls at the [Thierry] Mugler show, and they were gothic girls. That’s when it clicked for me.

PORTMAN: How do you work with designers at the shows? Do you meet ahead of time? Do you present to them?

PHILIPS: Each designer has a different approach. For example, I used to do Armani shows. When I worked with Mr. Armani, I approached him differently than when I worked with Karl [Lagerfeld] for Chanel or for Fendi. I think my background in fashion helps also because I know how much work goes into making those collections. A show is 20 minutes, and you come in two to three days before the show and have a conversation. Sometimes it’s just half an hour, and then you have to catch their vision and their idea. It’s not my vision; it’s the vision of the designer. I don’t consider it the Peter Philips show. When I worked with Karl at Fendi, there was always a sketch. Karl loves to draw and loves to tell a story. There’s always an inspiration of a painter. Dries Van Noten I always see, like, three to four weeks before the show, in Antwerp in his showroom with his collection. His collections are always finished two to three weeks before the show. So he’s got a different agenda. He is very passionate about everything. How he dyes his fabrics and how he layers different techniques. That’s a big inspiration. We did a whole show [fall 2016] with the story about the Marchesa Casati and how she illustrated the invitations. Actually, the illustrator was an artist [Gill Button]. She inspired how I did the makeup.

PORTMAN: Oh wow. Where do you usually get your inspiration from?

PHILIPS: When I do looks for shows, it’s the designer’s input.

PORTMAN: And for the products?

PHILIPS: For my collections in autumn, winter, spring, or summer, which are big collections, it’s a whole line. I find a story, which is linked with the house and with what’s going to be relevant in two years, because we work two years in advance.

PORTMAN: Oh my gosh. So what kind of thoughts go into that?

PHILIPS: It’s more of a gut feeling. I don’t want to analyze it too much because then you go crazy. You can’t know what’s going to happen in two years. Because I have been doing it for a while, you anticipate what’s going to happen color-wise and trend-wise. There’s no formula for it.

PORTMAN: And you’re creating the trend, too.

PHILIPS: It used to be that designs created trends because it was very seasonal. Spring, I don’t know, 1992, we’d done that trend. All the magazines had the same skirt lengths and that coat. Nowadays it’s different; there’s so much going on.

PORTMAN: Right, and it’s so immediate.

PHILIPS: It comes and goes. The women who wear the clothes create the trends. They have to be seduced now. The time of dating trends is over. I play a game of seduction. In my approach of creating products, I do it very respectfully towards women. I know women want to be beautiful. They don’t necessarily want to be trendy, but they all want to be beautiful. I make sure in my collections there are guaranteed products that guarantee beauty. Not too complicated. Beautiful balance. Beautiful lip shades. Then there is a little niche where I push it further to seduce women to maybe try something else. Everybody can do a green lipstick and say it’s the trend of the season, but not everybody wants to do a green lipstick. But if I do a beautiful range of pink and red lipsticks that are easy to wear, and I put a green next to it, then there is a choice.

PORTMAN: Since you’ve been at Dior, how has your vision evolved?

PHILIPS: I think my vision evolved with how everything else evolves. The last two to three years, everyone started talking about Instagram and Snapchat. Social media is huge. Everyone has a picture of themselves; they’re always out there. It’s almost like a photo shoot; it has a huge impact on how people make themselves up.

PORTMAN: That makes sense.

PHILIPS: For example, the whole highlighting and contouring thing. It started a little bit with Jennifer Lopez, when she started doing that natural Latin glow face, which was actually totally highlighted and contoured. And then the Kardashians came, and they always look picture perfect so they can take a selfie. [Because of the tutorials], they need products for that, and there is a huge desire for that. As a brand and as a house, we had to be active to provide.

PORTMAN: To fill that.

PHILIPS: There’s a huge hunger for all kinds of products. But again, it will evolve. It’s like in the ’80s with short pants and hair and then things became bigger and bigger and bigger. Now everything is over the top. It’s always like that. Last time I flew, when I checked in, the girl was highlighted and contoured like a proper drag queen. I was like, “Oh!” But I am sure in pictures she looked fantastic.

PORTMAN: Is that demand international, or is that more in the U.S.?

PHILIPS: I think it’s international.

PORTMAN: France is so different though, no?

PHILIPS: Yeah, it still is. The U.S. is extreme.

PORTMAN: L.A. is different than New York even.

PHILIPS: Yeah, and in Asia, Korea and Japan are also really extreme. The Middle East, it’s big lashes, big contouring. Each region has its own specificities. Maybe Europe might be a bit more real still, a bit raw.

PORTMAN: I remember those amazing metallic sticker liners that you did … What about the fun things like that? How often can you put those in the line? Where do those ideas come from?

PHILIPS: There’s a need for them. Those eyeliners were really great and were purely inspired on Raf’s [fall 2014 couture] collection. The venue was this arena in Paris, and out of the walls, which were mirrored like glass, came orchids. Real orchids. It was a contrast of this hard cut glass, rose gold, and this beautiful, fragile, alive thing that comes out of it. That’s something that you want to reflect in the makeup, to keep the face a beautiful, alive face, and slowly there was this razor-sharp eyeliner in the spotlight.

PORTMAN: It must be so exciting to invent something new that no one has ever done before.

PHILIPS: I have been able to showcase in a context that is really perfect. I don’t think I would have designed or launched that eyeliner without that context. Lots of girls wanted to wear it, also, because it became like a haute couture accessory. They could buy into the dream. If you’re not able to buy a haute couture dress, you can buy the eyeliner.

NATALIE PORTMAN IS AN ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING ACTRESS AND THE DIRECTOR OF A TALE OF LOVE AND DARKNESS.