FASHION

Paradigm Trilogy’s Katharina Korbjuhn on Magazines, Microtrends, and Manifestation

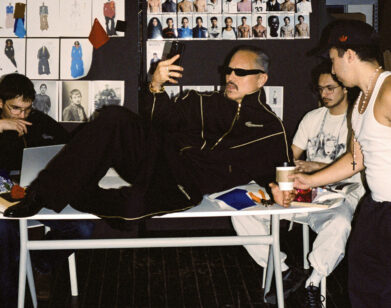

Earlier this month, Katharina Korbjuhn, the brains the alt fashion publication Paradigm Trilogy, celebrated the release of its third and final issue, Recognition vs. Expression, at The Roxy Theater in New York. Established as a means to connect with the creatives behind-the-scenes of the fashion industry, Paradigm is not your typical publication. More interactive trend report than glossy, the magazine has appeared as a PDF, an audiofile, and now, a short film starring Sydney Lemmon, Alex Consani, Eileen Myles, Aaron Rose Philip, Werner Herzog, and more. “I was feeling particularly tired of trend forecasting and cultural writing,” Korbjuhn told our senior editor Taylore Scarabelli over Zoom while on a recent trip to Florence. “I wanted to tackle larger topics that connect all of us, that are constant and eternal.” Part documentary, part fashion feature, the film poses several questions, the most poignant being: “What’s you without the bullshit?”

———

TAYLORE SCARABELLI: Hi. Good morning.

KATHARINA KORBJUHN: Good evening from Florence.

SCARABELLI: How is it?

KORBJUHN: It’s so nice. I just had lunch with Patrick from Vaquera. I just came here for no reason and I guess other people are doing that, too. It’s a Florence moment.

SCARABELLI: Love that. So let’s just jump in. For the laypeople, What is Paradigm?

KORBJUHN: Paradigm is a trilogy about the future of cultural creation channeled through a fashion magazine. I was consulting for the Tod’s Group and always would make these elaborate decks, almost like trend-forecasting, and I was like, “Wow, it would be amazing if there was a magazine that was speaking to creatives about their process, but also exploring different digital mediums.” So all of the issues have been a little bit interactive. There was an audio file for the first one and then the last was a short film.

SCARABELLI: I feel like this issue was really interesting because it’s a short film but it almost feels like autofiction. You’re speaking to the personal narrative that comes with being a creative, and the frustrations that come with working in fashion in particular. What was the genesis of that?

KORBJUHN: The previous issue was titled Man Versus Machine, and it was focused on AI and everything we can do with human intelligence and the brain. I was feeling particularly tired of trend forecasting and cultural writing because I feel like you can always manipulate a trend into existence by defining things in a very enthusiastic way. And so with this issue, I wanted to tackle larger topics that connect all of us and that are constant and eternal. I was also interested in creating something that was more embodied, which immediately led to the video format. I didn’t want to write theories. I wanted people to come to their own conclusions, so it was more about triggering associations or emotions and asking questions rather than giving answers or being an authority at all.

SCARABELLI: This is something I’ve been thinking about as someone who used to write a lot of think pieces. I don’t know if this is just my experience, but I do feel like there’s a fatigue around cultural critique in general. And I think it’s because culture is so splintered now that no matter what you’re speaking on, someone’s going to have some sort of argument against it. Whether or not these trends are “real” isn’t really the issue. It’s more that everything and everyone is so divided. I think now, particularly with fashion, the best way to speak to anything is through a personal narrative because otherwise you have nothing to stand on. And in a more existential way, your film reminded me of that.

KORBJUHN: And the title, Recognition Vs Expression, sums it up quite nicely because I feel like we often repeat things that have worked previously. And I think when things change, those mechanisms stop working. So I think if we stop depicting micro trends, it’s because we as a culture have moved on from that and we’re looking for the next big thing.

SCARABELLI: Which hasn’t actually happened, in my opinion.

KORBJUHN: Right. I unfollowed them but I saw a Highsnobiety post about someone having a new finsta the other day. I’m like, “That’s already the antidote of someone having a finsta, you making a headline about it,” and I was thinking about how journalism is almost canceling itself and serving the AI takeover because of those kinds of headlines. And by the way, I feel like Interview is totally outside of that bubble right now, but I feel like we’re in a dire place in terms of online journalism, especially in fashion.

SCARABELLI: Well, it’s just not really the way people are communicating right now. Journalism isn’t the language people are speaking. I was just thinking about this influencer Lyas, he does these really fun videos about runway collections. Some of it feels like it’s rooted in fashion knowledge, but mostly it’s just poetic. And I think that’s a very interesting example of what kind of “fashion criticism” lands right now, because aside from a few unbiased journalists, most of it is just some shitty writer regurgitating a press release.

KORBJUHN: Yeah. The whole is more than the sum of its parts. The question is how can you actually add something? Paradigm was never about, “I’m going to do this project and then it’s going to be my portfolio piece.” It was always like, “How can I actually reach people and give something to the reader?”

SCARABELLI: But I’m wondering what your personal frustrations were with the fashion industry before creating this publication, because you deal a lot with the conflicts that come with being a creative and monetizing those creative practices through self-promotion.

KORBJUHN: I think that we’re living in a time and in a system that asks you to keep your life private while at the same time turning yourself into a product. For example, Stéphane Sednaoui. He was a huge videographer. He did all the Björk’s most famous videos and Red Hot Chili Peppers and whatnot. He moved to the mountains of Japan because he couldn’t handle the industry anymore and wanted to do his own thing. He started making documentary photography and is sort of under the radar, but his body of work is much more aligned with his personal values. I find it so interesting that the culture we’re living in isn’t really interested in people and their personal trajectory. They’re more interested in a narrative that works within the system. And that is soul crushing to artists. If you put it in the art context, gallerists want you to do flatware and repeat the same type of painting that has sold before. The same goes for photography. It’s like the moment you step away from what worked, that’s representing a problem. So for me, the question becomes how can we change this stance?

SCARABELLI: Right. The other end is maybe we align ourselves too much with our work and we’re forgetting that these are actual jobs because of the expectations for us to brand ourselves within our creative industries. My current identity is Taylore the editor at Interview Magazine, but that just happens to be my role right now. I enjoy it and it is fulfilling in certain ways, but that’s my not entire identity as an artist or a writer or whatever. And you address that quite directly in the film—but there’s some humor to it too. You’re almost poking fun at our collective identity crisis, like when you show Alex Consani having a Britney Spears moment, shaving her head in the mirror, talking about how people in the industry own her. It’s campy. It’s profound and serious, but also hilarious.

KORBJUHN: Yeah, and that was my personal challenge because all of the writing comes from cultural theory. For example, we have Hanna Gabbie saying, “I’m sexy, I’m sad, I’m sexy, I’m sad.” It’s like Tiqqun’s Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl, where he basically says in capitalism every product—everything—wants to be a young girl, but we don’t want the girl to be happy. She should be hot, but she should also be sad. She can’t be fulfilled. So it was a challenge to myself, like, “How can I package something in the simplest terms so it can be understood by all and is really inclusive?” We were walking around in Florence and I was thinking again about how beauty is essential and not frivolous. And how I wish that more people would strive for beauty rather than making something complicated and hard to understand.

SCARABELLI: So do you think people take fashion too seriously or not seriously enough?

KORBJUHN: That’s a very good question. I think people take themselves too seriously. I think there’s very few people that care about fashion anymore and that’s making me very sad because the people that actually care about fashion, they don’t really appear that much. I feel like all of these gatherings that we’re going to, they’re mostly to be seen. It’s not to actually celebrate creation or let the creation speak. And so, I think we actually see very little fashion at the moment.

SCARABELLI: I’m interested because we’re coming on 10 years since the term normcore was coined. I’ve been thinking about it a bit and I’m wondering what’s changed since then, if anything? To me, that was kind of the end of subculture and I wonder if we’re just kind of caught in some perpetual pendulum swing, searching for something to grasp onto.

KORBJUHN: Yeah, I was speaking about that in the issue in some way, how I feel like there is no aesthetic that describes the now. And that’s quite interesting because if you continue that path, you’re like, “Where does that land?” It’s like de-physicalization. If we don’t have an aesthetic to create physical objects and that expresses our reality, then we are fully living in a digital world. When our screenshots are the best representation of now, then we’re handing it over to AI in some way. It’s kind of like the theory I wrote in the last one, which is postcore, it’s basically the convergence of all things at the same time. How many associations can I pack into one person? How many nods or references can I accumulate in one character that I’m building?

SCARABELLI: Yeah, but I don’t think that’s new, though. I think that that’s been going on for—

KORBJUHN: Since normcore, you think?

SCARABELLI: I fear that normcore has been that this whole time. But when you talk about there being less fashion, what comes to mind is that fashion has become synonymous with celebrity.

KORBJUHN: Yeah.

SCARABELLI: Do you think that there’s going to be some sort of burnout around that? Or is it the infinite end to how the fashion industry operates?

KORBJUHN: I think there might be an end to celebrity as we know it because I think we’re more interested in the people that are making the celebrities than the celebrities themselves. And that’s also the power of the internet, bringing those voices to the forefront. We know that celebrities aren’t picking their own clothes, aren’t picking their own makeup, so they’re just a display. So I think our idea of celebrity might progress actually back to people that are knowledgeable and—

SCARABELLI: But the behind-the-scenes people that do find a spotlight are also marketing themselves as celebrities in their own way. Law Roach is a good example of that. Whether it was intentional or not, he successfully used a retirement announcement in order to boost his own celebrity. But I’m also interested in how the fame pyramid is flattening a bit, which I think you’re also alluding to.

KORBJUHN: Yes, because, for example, Miley Cyrus had the biggest album of the year or something and I didn’t even know she had an album out. I feel like it’s not centralized anymore.

SCARABELLI: There’s no mega pop stars in the same way there used to be. There’s no Michael Jackson.

KORBJUHN: No. There can be a mega famous person with 50 million followers that I have never heard about. And I don’t know what that means for celebrity as a whole, but I miss leading figures. We don’t have any.

SCARABELLI: But perhaps it’s positive to not have culture be so centralized. I mean, it’s also scary because consumerism is so rampant right now. And when you think about the real issues with the fashion industry being that everyone’s just buying garbage all the time, that’s—

KORBJUHN: Yeah, what’s also interesting is that the power dynamic has already switched. Celebrity collaborations with fashion brands often benefit the celebrity more than the brand itself. So going back to your initial question, I don’t know if the celebrity for brand situation will continue forever, because now the middle class has broken away, people don’t have money, there’s inflation, and the next step is degrowth. Less brands. Have you watched The Century of the Self?

SCARABELLI: Yes.

KORBJUHN: The first episode is about Edward Bernays, the father of PR. I just rewatched it last night and it was so interesting because it was basically about the beginning of making people want things that they don’t need. Before, for example, fashion ads were about the most durable tights you’ll ever see. And then it was, “You can express your identity via these tights.” Now, I feel like we’re at a point where you don’t need to have a fixed identity anymore. You’re completely shape shifting all the time, and that’s another level of consumerism. But what’s beyond that? I don’t know.

SCARABELLI: And there lies the backbone of fast fashion. I wanted to ask you, who are you following in the industry right now?

KORBJUHN: Oh, my god, no one.

SCARABELLI: It can even be someone you’re fascinated with for whatever reason. It doesn’t need to be an intellectual pursuit, necessarily.

KORBJUHN: I mean, I’m much more interested in film. My own experience with the video was that it’s a whole different style of creation. The way you have to be vulnerable on set creates a much more interesting landscape to work in. It’s hard for me to go back after this experience. Also, I’m forever and ever will be a huge fan of Amanda Harlech. That’s maybe one person I would be starstruck by, because to me, she’s someone that was always dedicated to supporting creativity, but it was never about herself. I love the people that are just so in love with fashion that they will give their heart and soul, but they need nothing in return. I want to see more of that again. And then All-In, because I love that they’re bringing back fun and I feel seen by them as a woman.

SCARABELLI: I just bought some of the new collection.

KORBJUHN: You did? What did you get?

SCARABELLI: I just bought the little Allina dress and a pink slip skirt. I was like, “I wish this was actually a reconstructed vintage piece,” but I understand that’s hard to do production-wise. I just hate buying things new.

KORBJUHN: I watched the Galliano documentary and I saw how Anna Wintour basically made him, she supported him so much, and I’m like, “We need to support these guys.”

SCARABELLI: Absolutely. Okay, last question—and you can answer this however you want. What are your trend predictions for summer?

KORBJUHN: Paris will be a no-go because of the Olympics. I feel like it’s going to be a middle-aged woman on a laid back vacation summer, not a hot girl summer.

SCARABELLI: I love that.

KORBJUHN: Like, “I’m doing me with a pizza and a bucket of ice cream. Then I’m going on a hike in a big hat.”

SCARABELLI: No sun on the face.

KORBJUHN: Just some scarves, a little pashmina.

SCARABELLI: A little wine and cheese, whatever you feel like.

KORBJUHN: Eat, Pray, Love. [Laughs] I feel like I’m just talking about myself.

SCARABELLI: That’s okay. That’s how most trend predictions are formed. It’s all manifestation.