designer

Keke Palmer Talks to Lamine Kouyaté About His Prophetic Label Xuly.Bët

Lamine Kouyaté, the man behind the ’90s cult label Xuly.Bët, is known for the frenzied bricolage of traditional African fabrics and salvaged club-kid clothing that has characterized his designs for over 30 years. The fashion world first clocked the Mali-born, Paris-based designer at Paris Fashion Week in 1992, when Kouyaté and his models commandeered the area in front of Jean Paul Gaultier’s tent to present his inaugural collection for the departing audience. From these guerilla beginnings, Kouyaté amassed a devoted following for sculpting treasure out of trash: suturing scraps of deadstock fabric into a form-fitting dresses, transforming dyed stockings into technicolor halter tops, and layering looks with everything from latex to hosiery to denim in a colorful and feverish quest to avoid even the least bit of waste. Despite garnering considerable attention as a disruptor at the beginning of his career, Kouyaté’s work has flown largely under the radar in recent years. Nevertheless, his vision has proven prophetic: A collaboration with Puma in 1995 made Xuly.Bët the first known label to release a crossover collection with a sportswear brand. Through an array of upcycled tracksuits and dresses made from referee jerseys, Kouyaté signaled a seismic shift in the culture of fashion, from the halls of the atelier to the streets of the city.

As the pandemic tightens belts industry-wide, and fashion houses are facing calls for racial and gender equity, Xuly.Bët’s boundary-pushing designs, created without outsize marketing budgets or massive carbon footprints, have struck a chord with today’s youth. Kouyaté’s Fall Ready-to-Wear collection, an amalgam of slim-but-modest silhouettes emblazoned with gold lettering, proves that the designer still has more to say. And, as he tells the actor and musician Keke Palmer, the world is finally paying attention. — MARA VEITCH.

———

KEKE PALMER: I’m so excited to be speaking with you. This is just the coolest thing.

LAMINE KOUYATÉ: Thank you so much. I’m excited, too. I love your music.

PALMER: That means the absolute world to me. This is my first real introduction to Xuly.Bët, and I really did my research. While I was studying up on you, I realized I’ve been seeing so much Xuly.Bët for years without knowing it. I guess the best place to start is the beginning. When did your love of fashion begin, and why?

KOUYATÉ: I think it started with my mother. I come from Mali. Women there like to be well-dressed. Tie-dye is a very strong tradition in Mali. It’s very colorful there. I studied architecture, and I really didn’t believe I would ever do fashion. I came to it really late. I was, like, 27.

PALMER: Do you think that your architecture education played a role in the way you see fashion and design?

KOUYATÉ: There’s not much difference. A house is a house; you have to live in it. You have to feel really good there. You also live in clothing.

PALMER: Tell me about the name Xuly.Bët. It’s about the way we see ourselves, and how people see us. How long did it take you to find that name?

KOUYATÉ: It also came from my mother. She’s Senegalese. I spent my high school years in Senegal, and that’s where I learned the expression xuly bët [“Keep your eyes open” in the Senegalese language Wolof]. You cannot find it anywhere else.

PALMER: You mention your mom a lot. Who would you say you design clothes for? Is it for women like your mother, or men and women of all kinds?

KOUYATÉ: I like powerful girls, girls who really dig themselves because I was surrounded by powerful women. My aunt, my mom, they always struggled. I think it was my purpose to design better clothes for everyone, especially for women.

PALMER: It’s amazing to see that displayed through your work, and all the powerful women who have worn your designs. From Erykah Badu to Naomi Campbell, your clothing has so many different faces. What is the biggest difference between your designs from the early ’90s and your new collections?

KOUYATÉ: In the early ’90s, it was about faith. We were all really fighting to get somewhere. Now, we’re at the point where we’re focused on making things happen. Back then, there weren’t many people trying to bring youth to fashion. Fashion was just made up of the big houses. Now, we have this global youth audience.

PALMER: Yes.

KOUYATÉ: I’m African, but I have influences from all over the world. But so many systems keep dividing people, so I try to bring everything together. I’m trying to make old trash new. Recycling gives things from the past a new quality, it brings them back into fashion. Just like when musicians sample old songs and rap over them.

PALMER: It’s about not shying away from the ways that we can evolve fashion. What are some of the techniques in your designs that reflect your commitment to recycling?

KOUYATÉ: Mixing different deadstock fabrics. What else? Stockings. I put stockings over my denims, to make it like a sleeve.

PALMER: Where do you find your inspiration?

KOUYATÉ: I think it’s the music of the street. When I was young, I used to listen to a lot of Black music. I was fascinated by the creativity of Ann Peebles, Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, and Miles Davis. I also play music, but just as a hobby.

PALMER: Do you share it, or do you keep it private?

KOUYATÉ: I don’t share it at all. I’m scared to do that. It’s really garage rock, and kind of dark.

PALMER: You mentioned that fashion used to be much less inclusive. It’s a little more accessible now. How do you feel about that?

KOUYATÉ: The fact is we have to expand it more, and that’s what I’m trying to do. Most of the fashion world is still just about high prices and brand names. I’m more about style.

PALMER: Whenever I see a single trend take over the fashion world, I always wonder, “Is that lack of stylistic diversity the result of a lack of other kinds of diversity in the business?”

KOUYATÉ: Yes. I think it’s definitely because of a lack of global diversity on the business side.

PALMER: How do we make that happen? I guess the internet has helped a bit, giving exposure to new faces and new designers across the world who wouldn’t ordinarily be given a chance.

KOUYATÉ: Especially for young African designers, the internet has brought huge opportunities. Even for our brand, it’s better now. We can drive our own business through the internet. It used to be that the biggest barrier was getting to the market, but now that’s much easier.

PALMER: Are there any emerging designers you’re excited about?

KOUYATÉ: I really enjoy Selly Raby Kane, a designer who’s getting a lot more exposure from the internet. She’s Senegalese, and works in Dakar. She’s kind of radical.

PALMER: Speaking of radical—this is an interesting time, especially in America. How do the changes happening in society right now affect fashion?

KOUYATÉ: The fact is that people are conscious about the state of the world, but the work still needs to be done. We still have to push, because the institution would not have given us the opportunities that we have taken for ourselves.

PALMER: This brings me back to the beginning of your career. Some people said you were too far ahead of the rest of the fashion world. How do you feel about that now?

KOUYATÉ: I’m still really into the same movement, but I also have to turn my passion into a business. That’s the most difficult step.

PALMER: What were you trying to say when you first started designing clothes at 27, and how does that compare to what you’re saying now?

KOUYATÉ: People now understand what I was saying back then. Now there’s an urgency around race, diversity, sustainability, and everything else that I was always talking about. It’s time to solve these issues. I have a connection with your generation, because you’re speaking the same language now that I was speaking then.

PALMER: We say, “Hell, no. We’re not going to stand for it.”

KOUYATÉ: There are even riots in Mali now. People want their rights. No justice, no peace.

PALMER: Thanks to the internet, these movements are connected, and we all feel that we have something important to say. That’s empowering.

KOUYATÉ: It puts a face to some of the injustices that people wouldn’t otherwise know about. Speaking of the internet, how does your platform work?

PALMER: I use social media as a way to try things out. If I have an idea for a movie, I use my social media as a way to foresee how it will pan out. I think social media made me feel like I didn’t need to be afraid, that it was a place where I could try things without judgment, especially coming from such a traditional space, as an entertainer. I have one last question for you: How do you envision the future of fashion?

KOUYATÉ: I hope that we can be a whole lot funkier.

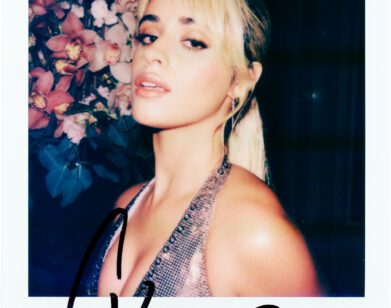

Why, you might ask, is the Swedish pop star Robyn in every single collage? It’s because she’s a longtime fan of the line who’s been wearing the clothes since the ’90s.

———

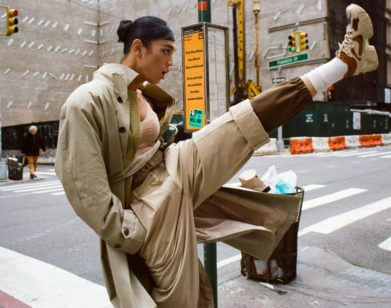

Model: Fatou Diarra

Photography: Ismael Moumin, Heji Shin, and Hannah Tw

Creative concept: Naomi Itkes and Konichiwa Records