Waking Up From Jean Paul Gaultier’s Dreamland

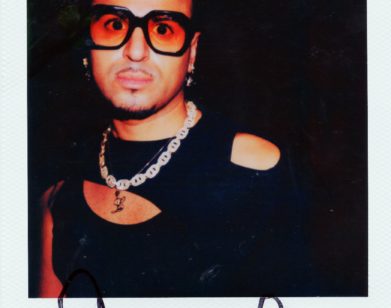

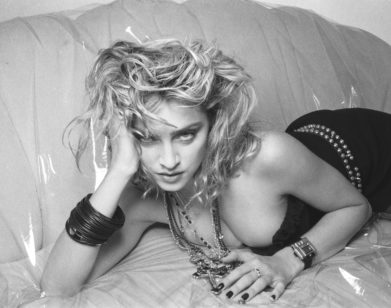

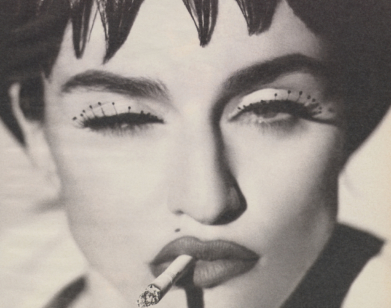

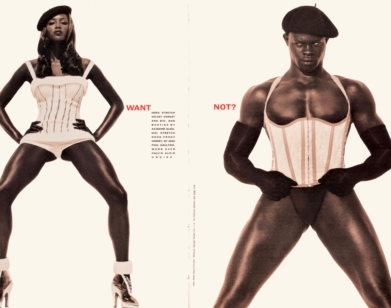

Jean Paul Gaultier held his final runway show this past Wednesday in Paris, where the designer—along with dozens of models, singers, and celebrities of every caliber—celebrated his 50-year-long legacy as fashion’s most provocative figures. Dita Von Teese, Karlie Kloss, Winnie Harlow, Coco Rocha, and both Bella and Gigi Hadid walked the runway at the Théâtre du Châtelet, with Boy George performing not once, but twice—opening the show with “Back To Black” and closing it out with “Church of the Poison Mind.” His final couture collection, numbering 200 looks in total, included references to his most recognizable themes: a deep admiration for camp aesthetics matched with razor-sharp silhouettes, both frivolous and futuristic, saturated with conviction that true fashion can be cerebral, banal, and boundless, all at once. The photographer Pierre-Ange Carlotti was backstage to capture the show, and below, we remember Gaultier’s legacy with selections from his conversation with Richard Pandiscio from our January 1994 issue, where the designer spoke about his Spring-Summer 1994 collection, his desires for inclusivity beyond the realms of fashion, and composing collections in his dreams.

———

———

RICHARD PANDISCIO: In the new collection you had some of your models wearing pieces of armor. To me this suggests a willingness to fight for your beliefs. Do you consider yourself an aggressive idealist?

JEAN PAUL GAULTIER: [laughs] A bullfighter! I am a Taurus. [In New York, Gaultier had shown me his new tattoo: the face of a bull with a nose ring in blue and white ink.] But I don’t consider myself an aggressive idealist—it is more about emotions. I try to translate what I sense from the street. So if you saw aggressive idealism in my shows, it means that this is what I felt from the people who are in the streets.

PANDISCIO: I was impressed by the video monitors you had installed in the window at your runway show in Paris so that people could watch from the streets. The crowd outside was big and very appreciative.

GAULTIER: I want to show my collection to the ones who are outside, the people in the street who are interested in what I am doing. It’s a way to thank them and give them something back. And of course, I am happy when the buyers and the journalists—the people in the profession, who are inside—come. But I want the maximum number of individuals to see what I am doing.

PANDISCIO: You design for customers who are young and idealistic by nature. Do you think idealists recognize one another and that may be the reason they are drawn to you?

GAULTIER: When I am making a show, it is not to speak to any particular group of people. I try to speak to everybody, to a lot of different kinds of individuality.

———

———

PANDISCIO: You seem to work to create an atmosphere that helps the audience understand your philosophy. In the ’80s your collections were often described as circus events. But recently your atmosphere’s been more like an international bazaar. The narrowness of the show’s venue indicates that you also want your audience to get close to the stuff. Where do you think the presentation of fashion will go in the future?

GAULTIER: For about the last three years I have been doing smaller shows because I want the people to really see my work, the fabrics, and the prints. That’s why I have only three rows to seat the people. If they want, they can also touch the fabrics. So the relationship between my clothes and the people who come to my shows is getting closer. Regarding your question, I don’t have the answer, to be honest. Sometimes you are frightened of change, but everything is possible, you know? It is true that this is a moment when anything is possible, which is great. But everything possible doesn’t mean that everything will be. It means that there is—something to do. But what?

———

PANDISCIO: Are there any new designers who interest you?

GAULTIER: Ah, there is one whom I truly love. That is Martin Margiela, my ex-assistant. I knew from the beginning that he would be excellent. I didn’t expect him to be as great as he is, though.

PANDISCIO: You told me what you dreamed about when you were a boy. What are you bad dreams now?

GAULTIER: That my collection doesn’t arrive, that I don’t know where the collection is or I don’t know where I am. Things related to my work. But I don’t remember very much from my dreams. I cannot say that I ever dreamed one of my collections. No. Never, never, never. Can you imagine doing the collection while you sleep? Fabulous, no?

PANDISCIO: Do you ever feel compelled to play the part of “Jean Paul Gaultier,” to play up to an idea people have of you?

GAULTIER: I don’t have to play myself, because I am myself. And what I have refused, since the beginning, is to have people protect me from bad reviews or bad realities. I try not to be ashamed about who I am or what I think. It’s funny, because when I was a schoolboy I was not so happy about my life. I was lying all the time. Like, when people asked, “Where’s your family from?” I invented a life for myself. At that time there was a war between France and Algeria. I knew somebody who had moved to my neighborhood from Algeria and whose family had suffered. I wanted to say that I had suffered, too, you know? I wanted to be interesting because I thought my life was boring. And when I started to work in the fashion business, I was a little ashamed of my relatives; maybe they were not as elegant as I wanted them to be. But after a while, I knew they deserved more because they are nice mentally. They are even nicer than some of the people who are fashionable. So after that I said to myself, No more lies.