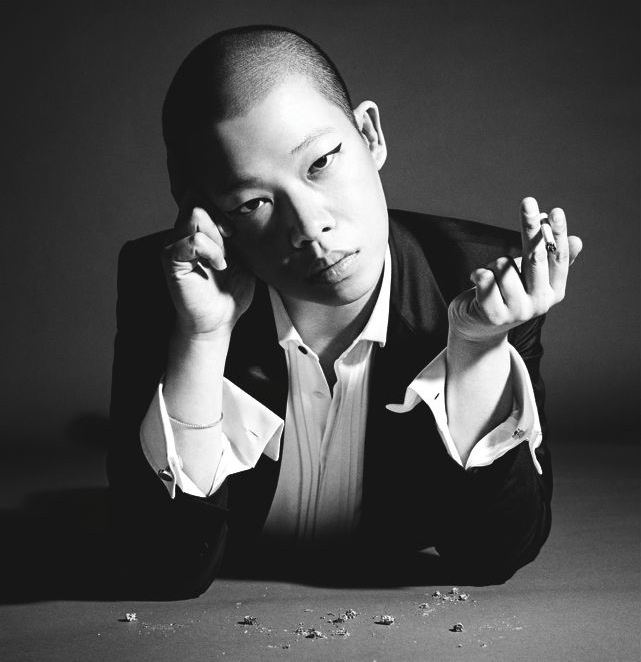

Jason Wu

I THINK CLOTHING IS TRANSFORMATIVE. IN SO MANY WAYS, WE’RE ALWAYS PLAYING A FORM OF DRESS-UP—IT’S JUST A GROWN-UP, MUCH CHICER VERSION OF IT. Jason WU

Over the past several years, Jason Wu has emerged as one of the brightest lights in American fashion—and remarkably, he has done it without ever neatly aligning with a particular wave or a trend. Wu is far from a prototypical young designer‚there is a widescreen elegance to his clothes, which embrace a sort of sweeping old-school glamour. But they’re still ultra-contemporary, embodying a modern and youthful kind of femininity that sidesteps all of the clichés.

Fashion, though, is often reduced to moments, and it doesn’t hurt that Wu has been involved in two defining ones: the first, of course, occurred in January 2009, when newly minted first lady Michelle Obama wore a white one-shoulder dress of Wu’s on inauguration night; the second occurred earlier this year when the first lady surprised the world (including Wu) by wearing another of his dresses—this one, a vibrant red—on the evening that her husband was sworn in for a second term. In both cases, Wu was far from the predictable choice—in the first instance, rising from relative obscurity as a 26-year-old with a burgeoning line and just a handful of seasons under his belt, and in the second, with the cards apparently stacked against him precisely because one of his dresses was picked the first time around. But if Wu has proven anything in his brief career thus far, it’s that he has an almost uncanny knack for beating the odds—or more accurately, ignoring them entirely. What sets him apart is that he has never appeared to be out on some quest to crack the code for what makes fashion cool; rather, he has demonstrated a sharply attuned instinct for how women today want to feel and be perceived, which belies a talent more timeless than timely—and one that has many people predicting a lifetime of big moments for him.

Stephanie Seymour Brant, who appeared in Wu’s Spring 2013 campaign, recently spoke with the designer, now 30, at his studio in Manhattan.

STEPHANIE SEYMOUR BRANT: My mom was always a major fashion groupie. She was always way too stylish for anyone where we lived to really appreciate. Was your mom like that?

JASON WU: You know, it’s funny because, in the ’80s, my mom always wore those power suits with her hair in a chignon. She was in the restaurant business, and then she had me and my brother, and stopped working, but she still dressed up, and the way she dressed was one of my earliest inspirations—in those ’80s suits with shoulder pads and things like that. For years, I ran away from that style. I came of age in the ’90s, so I was kind of into a different thing. But now, all I want to do is shoulder pads and nipped-in waists and padded hips and peplums and poufed dresses. That’s all I like now. But for the longest time, I was like … [makes whining noise, then laughs]

SEYMOUR BRANT: Fashion kind of went from what was happening in the ’80s, when everyone had a really distinct style, to the ’90s, which was this transitional period when everyone was sort of grabbing from every period of fashion.

WU: It’s interesting because I was in San Francisco recently, and I found this vintage store that had all of those Christian Lacroix pouf dresses from the ’80s. They look so relevant now—like, all you’d have to do is a couple of things to adjust them or remake them, and they would be dresses that you could buy now. There were these Ungaro dresses from the ’80s at this place. That’s what I’m loving right now. I mean, I’ve always loved that, but now more than ever.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Did you do that when you were a kid—kind of remake things instinctually?

WU: Yeah. I remade Barbie clothes. I would buy Barbies and take them apart and then remake their looks.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Oh, really?

WU: I know. [laughs] I used them for hairstyling. It was a whole process. I had a lot of dolls—like 150.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Wow.

WU: I know—my mom was really indulgent in letting me have them, which was unusual for Asian parents because Asian parents would not let you have that kind of thing. My mom was really cool like that.

SEYMOUR BRANT: How did your father feel about it?

WU: He bought me dolls, too. It was so against everything he believes and understands, but he did it anyway.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Why do you think he did that?

WU: Well, my parents loved me, and I think they realized that I was probably not going to have a normal 9-to-5 job. For the longest time, my dad thought that I was just going to be home until I was, like, 35—which, weirdly, is completely normal in Asian families. It’s not like in American culture where you leave home at 18. In the Asian culture, your parents don’t really want you to leave home. So they just thought I was going to be one of those kids. I was like, “I’m never going to make a living at whatever I do.” I just liked pretty things. I didn’t know what fashion was, though. I didn’t understand anything about fashion until I moved to Canada when I was 9. That’s when I learned English and was exposed to fashion magazines like Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue.

SEYMOUR BRANT: You moved to Vancouver, right?

WU: Yeah, I moved with my mom and my brother. My dad’s company was in Taiwan, so he went back and forth.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Why did you move?

WU: It was my mom’s choice. I was really not fitting in at school. My brother was a really good student, but I was having a really hard time, so the move was mostly for me.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Why do you think your mother chose Vancouver?

WU: Vancouver was quiet and there is a big Asian community there. We didn’t have family in Vancouver, but we moved during the time when Hong Kong was about to be handed back over to China from the British regime. A lot of Chinese people there thought that was going to make a huge difference, so they started moving to either Australia or Vancouver—those were the two main places.

SEYMOUR BRANT: I wonder why Australia or Vancouver.

WU: I don’t know why. I think it was easier back then than moving to America. I mean, we had friends who did it. We knew six or so other families who did the exact same thing that we did. But I think my mother really sort of instinctually knew that it wasn’t going to happen for me in Taiwan.

WHAT I WAS INTERESTED IN WASN’T POPULAR AND YOUNG, BUT I NEVER REALLY DEVIATED FROM DOING IT. I JUST DECIDED THAT I WAS GOING TO GO FULL FORCE INTO EXACTLY WHAT I WANTED.Jason Wu

SEYMOUR BRANT: Did you experience a lot of bullying at school for being different?

WU: Not when I was in elementary school—that was a bit later … I had a hard time in middle school. I was never really quite me until I was 16 or 17, and things like that didn’t matter anymore. You know, everyone is sort of in your business in Asian families, and they didn’t think that what I was into was appropriate, and they would tell my mother, and she would get really bothered by it. So she said, “Let’s just move.” So that was that, and it was from there that I was able to get my first sewing machine. My mom hired a fashion student to come teach me how to sew twice a week.

SEYMOUR BRANT: That’s so amazing.

WU: And then I had the Barbies, so I would dress them. My mom would give me, like, $200, which was a lot of money, and I’d go downtown to the fabric store and buy a little piece of the expensive fabric that was in the glass case—of course.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Of course. [laughs]

WU: Always the most expensive. And all you could buy was like a half-quarter yard. But I would take that and draft patterns to make clothes for the dolls.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Would you do that with fashion students that your mother hired?

WU: Yeah.

SEYMOUR BRANT: So your mother is, in a lot of ways, responsible for what you’ve been able to accomplish. She opened you up to the possibility of being a designer.

WU: She did. Without her, my life would have been so different.

SEYMOUR BRANT: There is that parallel in your story with the stories of so many other male designers who were encouraged by their mothers—specifically, one of your favorite designers, Yves Saint Laurent, whose mother allowed him to make her clothing. She hired a seamstress and they would buy fabric and she would wear all of his designs. It’s interesting because I think that for many designers, the mother is really the first muse.

WU: People say that mothers always know, but in this case, she really did know. But she didn’t understand it. She had very good taste, but she didn’t understand what the fashion industry was. For a while, I just thought that I wanted to be an illustrator because that’s all I wanted to do. I also did some sculpting. It was always very artsy and very feminine, everything that I did. But she just supported me throughout the process.

SEYMOUR BRANT: She knew you were an artist.

WU: She did. I remember that she once told me, “You know, artists don’t make anything until they die”—like Van Gogh. [both laugh] She was like, “People don’t appreciate what artists do until they’re dead.” I was like, “Oh, well …”

SEYMOUR BRANT: Well, there was something to that maybe in the past.

WU: But it’s so different now.

SEYMOUR BRANT: It is—especially for designers. Designers can really define a woman’s identity. There are also so many women throughout history who have created a sort of lifeline and developed this collaborative relationship with their designer of choice, and it has defined them.

WU: Yeah. I think clothing is transformative. When you put something really beautiful on, you feel something. In so many ways, we’re always playing a form of dress-up—it’s just a grown-up, much chicer version of it. It’s nice to be able to be whoever you want to be. I moved to New York for that reason. I think I am a very good example of how you really can do whatever you want to do without having any kind of prerequisite experience of any of kind of connection. I mean, none of my family members came from this world.

SEYMOUR BRANT: How did you dress as a child?

WU: I was very preppy. I also went through an anti-clothing moment where I just wanted to wear sweats because I’d just moved to Canada. My mom was always trying to get me into proper clothes, but I never wanted to wear them, and now that’s all I wear. So, again, it goes full circle. It’s interesting because when we moved to Canada, there were these “monster houses,” which is what the Canadians called them. They were these completely new houses. Some of them were even expensive, but they were done on, like, a production line. They all had marble floors and gold railings and faux French-style fencing. They were huge, but sort of generic-looking, like they came from a factory. A lot of Indian and Chinese immigrants bought them.

SEYMOUR BRANT: What year was this?

WU: This was in the early ’90s. But I thought these monster houses were the coolest things, because our house was 70 years old and small and had a lot of character—which, to me, was not good at the time. I was like, “I want marble floors and gold railings and tacky tiles …” [Seymour laughs] That’s what all my friends had, and their houses were much bigger than ours.

SEYMOUR BRANT: What did you mother tell you when you complained?

WU: She was like, “Our house has personality, and you’ll know later that you don’t want what everyone else has.” At the time, of course, I didn’t agree, but now, looking back, the last thing you want to be in is one of those pre-fab spaces.

SEYMOUR BRANT: So your mom had her own style in decorating and art as well.

WU: Yeah. We also had old furniture. My mom used to take me to antique shows, which I hated because everything was so dusty and old and there were all these weird ladies selling their antiques … We call them “eclectic” now. [laughs] But it was really amazing that I was exposed to that when I was younger. Now that I have my own taste, I understand it more.

SEYMOUR BRANT: What kind of architecture or furniture are you interested in now?

WU: I tend to like midcentury things.

SEYMOUR BRANT: American or French?

WU: American. I just find things here and there—like this table. It’s a piece of wood, but there’s just this sense of character.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Clean lines.

WU: Yeah, clean lines. I’ve always loved them.

MY PARENTS LOVED ME, AND I THINK THEY REALIZED THAT I WAS PROBABLY NOT GOING TO HAVE A NORMAL 9-TO-5 JOB. FOR THE LONGEST TIME, MY DAD THOUGHT THAT I WAS JUST GOING TO BE HOME UNTIL I WAS, LIKE, 35. Jason Wu

SEYMOUR BRANT: You have a lot of them in your work. If you could live in any kind of house and decorate it in any way, what do you think you would design?

WU: I think I’d want the contrast of something quite modern and something quite classic. I’d take an old house and flip it into something very modern inside—or the other way around. But I would also love to take an old space and restore it to exactly the way I want it. Like an old factory—just something with great bones and lots of character.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Do you collect things?

WU: I don’t collect per se, but I do pick up things as I go. Like, here, in the studio, I have an old sewing machine from Germany that my dad gave me, and then something else that I got from a friend in India, and a piece of flooring from one of my shows.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Do you work with inspiration boards?

WU: Yeah, tons. My inspirations come from everywhere. It’s important to look at everything and anything. I think what I create is serious fashion, but I don’t want to keep my focus on that. You have to look at a lot of different things. I mean, people are always surprised when they find out that my favorite show is RuPaul’s Drag Race. [both laugh] I love that era RuPaul came out of because it was around the time that I first discovered fashion. I remember M.A.C’s first Viva Glam campaign had RuPaul in a little red bustier, which was like to die—but I thought that he was a she. That campaign was amazing—like, red legs for days. So I was infatuated. I went out and bought RuPaul’s first CD Supermodel of the World [1993]. It’s the best CD ever. [sings] “Cover girl, work it girl, give a twirl …” Later, of course, I found out that it was a man. But he was so tall and glittery and impressive, with the big hair … You know, a fashion-obsessed boy would be into that.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Well, you seem to have a very evolved sense of taste.

WU: I think it’s important to be open-minded. I’ve lived in so many places in my life. After I lived in Canada, I went to boarding school in Massachusetts.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Where?

WU: Eaglebrook in Deerfield. Then I went to Loomis Chaffee in Connecticut. I had a difficult time at Eaglebrook, though. I was one of the few Asian kids. I’d never been alone, and I felt like they just didn’t know what to make of me. I was 12 or 13. I already knew that I was gay. And then my interests were not conventional. So I was very different—in every sense of the word. And in an all-boys school, that’s tough.

SEYMOUR BRANT: How is your family with the fact that you’re gay?

WU: My parents are very comfortable with the way that I am, and I think they’ve always been. Without that, I don’t think that I would have ever have been able to grow into the person that I am today. I never felt like I was hiding anything from them.

SEYMOUR BRANT: That’s wonderful. What are some of your favorite films?

WU: I love Breathless [1960]. Jean Seberg is always, forever, a great icon. Last Year at Marienbad [1961] is great, too. And then I love the original The Women [1939]. I’ve also always loved Roman Holiday [1953]. I was like, “I don’t care if Audrey Hepburn is a well-worn reference. I love her.” Also, do you remember To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar [1995]?

SEYMOUR BRANT: That was one of Patrick Swayze’s best movies.

WU: And Wesley Snipes as a drag queen is hilarious. And then I love horror movies, like Ringu [1998], the Japanese version of The Ring.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Do you ever put a film on while you sketch?

WU: I always have the TV on. I mean, I used to more, when I did more work at home. But now that I’m here, there’s no TV, so I play music. I like having noise. I think that’s why New York is so suitable for me, because it’s never really fully quiet.

SEYMOUR BRANT: There’s something a little bit frightening about silence.

WU: Yeah. I need to feel like I’m part of something. I need to feel part of the world when I go to sleep.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Do you stay up late and work in your atelier? Do you like to work by yourself?

WU: I love coming in on Saturdays when no one is here. That’s when I’m most productive.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Are you archiving your designs?

WU: Yes, I am. The wear and tear that the samples go through today when they’re sent out is crazy, because they have to go out to so many magazines and trunk shows. Nothing upsets me more than a wilted piece of clothing, so I restore the clothes when they return.

SEYMOUR BRANT: That’s wonderful that you do that.

WU: I have to do it. It’s not even an option for me not to do it. It’s hard because you’re always in the mode of creating the next season—and we used to do two seasons and now we do four. It’s so fast, and in two months, the collection you just did is already old, and it’s always next, next, next. So I woke up one day and I was like, “I don’t have anything to save for myself for the future.” That’s when I started archiving things. Now, I take four or five things that are really key to each collection, and I restore them or, in some cases, remake parts of them, and archive them. I used to just keep them in my studio, but I didn’t have enough space, so now they’re in an art-storage facility in Queens. It’s nice because I feel like there’s a sense of legacy. I also ran into Isabel Toledo. She had just done her FIT exhibition, and she said, “Don’t give anything away. Always keep a copy for yourself because I had to go buy things back and go out and find them.” That’s when I realized the importance of archiving. So I save key pieces, as well as any red-carpet things that become iconic. I always ask for that stuff back. I’m like, “It’s going in my archives.”

SEYMOUR BRANT: You dress so many great women. Is there anyone in particular who you really enjoy dressing?

WU: There’s something to be said about a girl who knows what she wants. One of my favorite girls to dress is Diane Kruger. It’s always so easy with her. I know her body and what works. When it’s right, it’s not a lot of effort.

SEYMOUR BRANT: That’s how the best designer-woman relationships have developed.

WU: It’s quite a pure relationship, designer and muse. I think a beautiful dress on the wrong woman could mean nothing. It has to be the right woman and the right clothes. That’s why you need that personal touch. I mean, that’s why I went into this business to begin with. It certainly wasn’t for the easiness of it. This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done, being in this business, because that’s what it is at the end of the day—a business—and you have to make sure it works.

SEYMOUR BRANT: I loved your last show.

WU: Thank you. It was very Stephanie.

SEYMOUR BRANT: It was. [laughs] I felt like each of the girls had their own individual style. You didn’t just look at the show like it was models wearing clothes—they really looked like women who were sensual and sexy and exciting. The colors were also amazing.

THERE’S SOMETHING QUITE BEAUTIFUL ABOUT A WOMAN WHO JUST PICKS SOMETHING THAT SHE HAPPENS TO LOOK GREAT IN … IT’S REALLY COOL THAT THERE’S A FIRST LADY WHO WEARS ALAIÌ?A OR JUNYA WATANABE. Jason Wu

WU: It was fun, all the textures and everything. That was like my big-shoulder, little-waist collection. A lot of them had really big shoulders because I was like, “This seems so right now.” It’s all I wanted to do. But a lot of time and care also went into choosing the right models and the fittings. There were a lot of womanly bodies, which I love.

SEYMOUR BRANT: They had form. They weren’t all just skinny.

WU: I would say that I love a little tits and ass. [laughs]

SEYMOUR BRANT: It’s natural. Who doesn’t? But tell me about the combinations of fabrics that you used?

WU: The coats were velvet, wool, duchesse satin—I love the idea of satin for day—and mink and fox. It was extravagant materials and lots of chiffon with, like, a polka dot devore inside, and then pleated, like Madame Grès-style.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Watching the show, I could see little bits of inspiration that I thought came a little bit from Saint Laurent, Grès, or Alaïa. But what I thought was most impressive was that it was all completely yours.

WU: Thank you. I think it’s really important to make things your own in your voice. I started when I was 23, and in the beginning of my career, there was this expectation of a young designer being edgier, cooler, more downtown. But I was never that person. It was certainly a pressure—all of my peers were like that. The polishedness and the sophistication were what I was interested in. I mean, give me a polka dot, a floral print, a pleated dress, a big fur coat—that was always my language, and it wasn’t very “in” when I was starting out, so I had a difficult time in the beginning. What I was interested in wasn’t popular and young, but I never really deviated from doing it. I just decided that I was going to go full force into exactly what I wanted. I think there’s a certain comfort that comes with age and experience, and when I got that, I think my work got better. There was much more authority in it.

SEYMOUR BRANT: You can’t deny your own style.

WU: You can’t deny it. But it was difficult in the beginning. Now, we’re into glamour again. But we weren’t really into glamour five, six, seven years ago.

SEYMOUR BRANT: But you can’t help what you are.

WU: And I think the second that I came to terms with that, I was totally fine. The worst thing is to be a designer and create work that isn’t honest. You have to be honest. Otherwise, you’ll always be a reaction to what other people do and you’ll always be one step behind. You have to just do whatever you want to do. The second I came to terms with that, it transformed my work. You know, I was at the Yves Saint Laurent exhibition in Paris—the retrospective at the Petit Palais—and they had this room where it was all the bad reviews done as wallpaper, which in thought was so amazing. Because looking at them, you’re like, “The work they’re talking about is so genius and relevant now that I don’t see how anyone could say anything bad about it.” But at the time, people did.

SEYMOUR BRANT: The same thing happens with artists. Would you ever want to collaborate or do something with an artist?

WU: Well, I worked with KAWS last year. But I love Cy Twombly. Robert Rauschenberg, too. I’ve always wanted to do a collection about that. It hasn’t come time yet, but a collage-y collection could be really cool. I didn’t say it in the press because it didn’t really become that in the end, but when we started the Fall collection, there was some Josef Albers in there with the reds on reds and reds, those squares. The runway itself was inspired by Carl Andre—I liked the idea of this metallic, pieced-together kind of thing. That was the process of where it came from. But there was a big Josef Albers influence because of the lines, squares, and things. The color sense really came from there. The black, white, gray, and red is a very Albers thing–and then the three different reds together.

SEYMOUR BRANT: You should do an Yves Klein collection.

WU: That last dress [in the Spring collection]–the Yves Klein blue. I made an eye shadow out of that color … Although you’re on my screensaver, I swear it’s not done because of you.

SEYMOUR BRANT: I love being your screensaver. I’m honored. So you did a makeup line with Lancôme?

WU: Yes. This one will be the first.

SEYMOUR BRANT: But you did one with Shiseido as well, right?

WU: A few years ago, yeah. But I just did an eye shadow collaboration. This one is long-term. It debuted at the show–the Yves Klein eyes. But I look at tons of art. I just saw this exhibition by Barry McGee at ICA in Boston with these old printing plates. I do a lot of 24-hour trips, and wherever I am, I always try to go to a gallery and see a show, because you always run into something.

SEYMOUR BRANT: What about jewelry? Do you look at jewelry from any period?

WU: I love fine jewelry, but I don’t know so much about it. You’re the expert, so I think we need to have a discussion. But I love those old Van Cleef books. That period was so beautiful.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Have you had a chance to meet any of your fashion heroes?

WU: I’ve had a chance to meet a lot of amazing people, but one person who I’d always wanted to meet was Kevyn Aucoin. Unfortunately, he passed away just after I moved to New York, but I always wanted to meet him because I love makeup. I have his books, Making Faces and Face Forward. He would transform Gwyneth Paltrow into Faye Dunaway, or do Lisa Marie Presley as Marilyn Monroe—Martha Stewart as Veronica Lake was a really good one. But, again, the idea of transformation is super-important to me. You can see it in the way I approach things. I have never been a clean-faced, freshly scrubbed hair person. I’m the New York designer who doesn’t do that. I think about the hair and makeup almost as much as I think about the clothes because it all has to work. I look at the models as women, and it all has to come together. I’ve worked with the same team for the longest time.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Who do you work with?

WU: Odile [Gilbert] and Diane Kendal. They just get me. We can talk about things. And I love the idea of working with women because I always feel like a man designing womenswear needs women around him to really have a sense of what they’re doing. There is something that I can never experience about my own work, and that needs to come from these women around me.

SEYMOUR BRANT: In terms of hair and makeup for the shows, what do you think is the most important idea to keep in mind?

WU: I think it’s always important to go for the look. This season was all about the purple eyelid, and we had that Yves Klein blue dress at the end, which was really off the wall, because the collection was very monotone and it didn’t have a lot of bright colors. So the idea was that the makeup was part of the color story—it was not in the clothes. I just loved the idea of this intense blue eye, something very graphic—again, that Albers aspect where it’s really blue and shaped and saturated in color.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Have you ever been to a psychic?

WU: No. Actually, I was talking to a friend of mine who is a stylist the other day and I was like, “I have all of these decisions to make in my life right now and I don’t know what to do.” So she said, “Why don’t you just go to psychic? She’ll just tell you.” I was like, “I don’t know if I want to know.” The only remote psychic I know is her sister, who is a healer. I always listen to her, but she’s not specific.

SEYMOUR BRANT: I know that everybody always asks you about the two dresses that you made for Michelle Obama. But the idea that you made the first one before you had ever met her shows how tuned in you are to the women you’re designing for.

WU: It’s interesting how the two happened because I didn’t really know her and, for the most part, had just studied pictures. Anyone who knows me knows that I don’t know anything about politics. Every time I go to Washington, I feel like I’m in Legally Blonde. [Seymour laughs] So I didn’t look at her as a first lady. Actually, the first dress happened before she was first lady. I didn’t know her—I just had her measurements. So I googled pictures of her and read about her and tried to understand who she was as a woman. Her style was still evolving at that point. But we’ve kept up a really great relationship all through the last four years. I think we shared a moment that was such a surprise to both of us because we didn’t know that it was going to be that big of a deal. But it really was just one of those moments: right place, right time, right person. There’s something that’s Kennedy-like about President Obama and her because they’re young and energetic, but in a modern way. There’s something more than just the clothes she wears that everyone relates to so much with her—people appreciate the sense of realness about her. So in designing for her, I tried to sort of be in her shoes, but I didn’t really look at her as an important political figure. I looked at her as a woman who would like to wear a beautiful dress to an important gala. That was really it. And with both dresses—I swear, this is the truth—it was the first thing that came to mind. The first one—the white dress, with one shoulder—I sketched it up and made the dress and sent it over. I delivered it to Chicago. I remember that I cancelled Thanksgiving to deliver it to the woman that she was working with at the time because I was not going to leave it to fate. I was not going to stick her dress in a FedEx box.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Did you fit it on her?

WU: I did not fit it on her. Her team did—I hadn’t met her yet. The second dress was quite different because, in so many ways, I know her so much more now. So it was much easier in that one aspect, but also much harder because everyone was already clued in on this other big thing. Of course, no one expected that I’d design another dress for her because I did it the first time. So I was sort of able to go unnoticed on the second one for a while, but it was also the only idea that I came up with. It had to be a red dress—and she agreed. So it was all about instinct and what she would wear. And it was funny because it was the first idea. There was a slimmer version and a fuller version, but that was it. Of course, much later on, people start to dig into the symbolism and everything. But I was just like, “I think red is a good color on her.” And there’s something quite beautiful about a woman who just picks something that she happens to look great in.

SEYMOUR BRANT: The white of the first dress symbolizes a beginning, so the second dress being red is—

WU: Confidence. Authority.

SEYMOUR BRANT: She has so much presence. She can wear anything. She can wear Alaïa or J.Crew. But whatever she’s wearing, she always looks like herself.

WU: It’s really cool that there’s a first lady who wears Alaïa or Junya Watanabe. I only realized this much later on, but you go to Washington, and so many women are in these boxy suits and ill-fitting clothes. But then you look at her in a room … I remember I was at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, and she came out in this pink dress. It was just a little dress with a big necklace, but it was cool. It was body hugging, a little sexy, but still appropriate. In a room like that, you realize how groundbreaking she is.

SEYMOUR BRANT: She puts a lot of effort into how she presents herself, which is really something to be applauded. Because a lot women who are in the more political or intellectual spheres—they don’t really want to have to care. It’s like, “Give me a suit.” But she does care, and it inspires people.

WU: I think she made it a thing to not be afraid. Yes, she’s the wife of somebody, but she’s also a person in her own right, and what she brings to the table is liberating, because it shows that you can be sort of sexy or glamorous and still very serious at a job. It used to be a bad word in some ways, style. So I guess I accidentally became a part of history. Honestly, when you’re young and you’re a designer, you have a goal, but that is not the kind of goal that you even think it’s possible to achieve. You say, “Anything is possible.” But really, you don’t think something like that is going to happen.

SEYMOUR BRANT: Last question, in honor of Andy: If you could come back as anyone or anything, who or what would it be?

WU: I don’t know if I would want to come back as anything but me. I feel really satisfied. I don’t really want to be anyone else. I don’t know if that’s a good answer.

SEYMOUR BRANT: That’s a great answer.

WU: I just feel like I’ve gotten everything I signed up for as me. I’m happy as me.

STEPHANIE SEYMOUR BRANT IS AN ICONIC FASHION MODEL. SHE IS CONSIDERED AN EXPERT IN THE WORLD OF HIGH FASHION, AND WAS THE FACE OF JASON WU’S SPRING 2013 CAMPAIGN

To read Jason Wu’s 10 favorite things, click here.