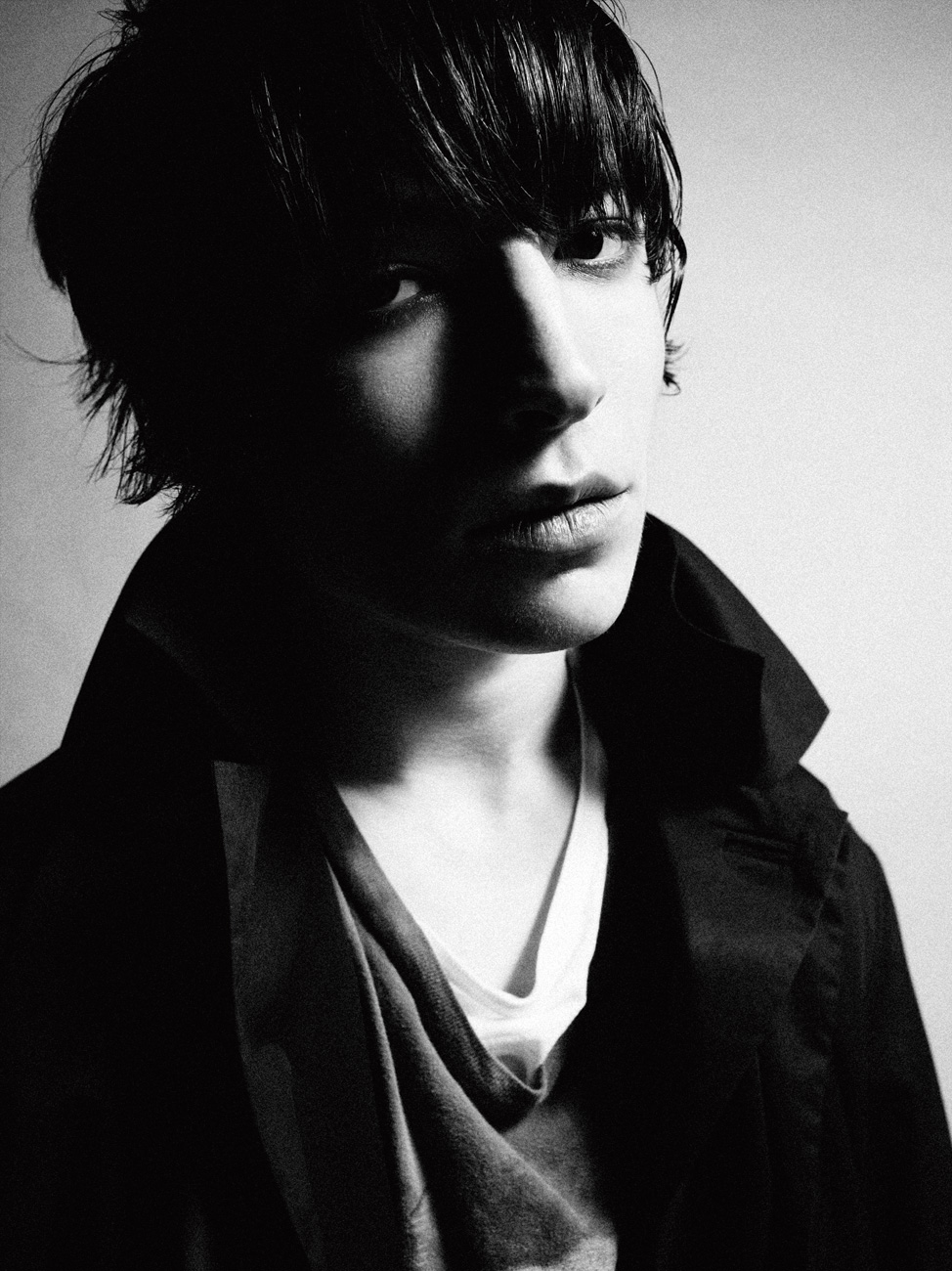

Ezra Miller

When Ezra Miller was 6 years old, he received an unusually highbrow introduction to the performing arts. He performed in the U.S. premiere of Philip Glass’s contemporary opera White Raven, a role that involved daily trips into the city from his suburban New Jersey home, a familiarity with Luísa Costa Gomes’s libretto, and, most importantly, a precocious professionalism that led to a grade-school residency at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Miller, though, soon turned to acting and abandoned the mezzo-soprano crystal palace for scruffier, edgier territory, quickly scoring a five-episode run on the Showtime series Californication; playing an alienated Web-porn-addicted teen who chronicles the unexpected death of two popular classmates in Afterschool (2009); and taking on the role of a lonely Bronx kid with an obesity fetish in last year’s City Island, amongst other projects. But in two new independent films due out this year—also stark studies in childhood rebellion and familial dysfunction—Miller gives standout performances that pull together a complex web of all-too-human contradictions and have him poised for a bona fide breakout. In Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, he stars alongside Tilda Swinton as a kid who, just shy of his 16th birthday, goes on a killing spree at his high school. And in Sam Levinson’s Another Happy Day, one of the more talked-about films at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, he plays a drug-addled teen struggling to negotiate his self-obsessed parents and equally damaged siblings. KateBosworth, who plays the 18-year-old Miller’s sister in the latter movie, recently sat down with him to talk about his seemingly breakneck rise, the heady business of playing unhinged, and what it’s like to be the indie-film world’s new King of Adolescent Pain.

KATE BOSWORTH: Where are you from originally?

EZRA MILLER: I’m from the dirty depths of New Jersey.

BOSWORTH: I always forget that you’re 18.

MILLER: It’s good to be 18. For a long time I felt like I was fighting my age, like I was constantly trying to prove to people that I was a savvy peer, and I felt them viewing me as a kid. I was a cocky kid, and I felt like I was an adult at, like, 9, you know? I think that’s because my parents always treated me as an adult.

BOSWORTH: I think that’s the way to go. I’m an only child, and I was always around adults, so I felt like an adult at a very young age. Did you like growing up in New Jersey?

MILLER: No. [Bosworth laughs] Not at all.

BOSWORTH: But did you have friends? Did you like school?

MILLER: No! I always was very interested in intellect and the massive world of knowledge out there, but in terms of being a kid who wanted to be treated as an equal, school is not the place.

BOSWORTH: There’s an enormous amount of pressure to get the highest grades, to get into the best schools, and even though I worked really hard in high school, I didn’t take much in because it didn’t feel like a joy. It felt like a pressure.

MILLER: Yeah, and there’s no true value placed in learning, if the point of you learning something is to simply know it for a test, to get a grade, to go to the good school . . . It was all too indirect.

BOSWORTH: And it’s ironic, coming from you. When I walked into your hotel room in Detroit, you had books on neuroscience.

MILLER: Right! Because that shit is fascinating! But it’s not fascinating if a really boring person is droning it at you and you’re sitting in a seat and you’re not allowed to move, and if you don’t do it there’s some sort of consequence. That all made it very unappealing for me. I love my family and I had a very wonderful,magical childhood. But New Jersey was actually a very cold place. There was such an intense concentration of wealth, and such a low concentration of any actual human happiness. A lot of people seem to be similar to the kid in school, which is doing a lot of things with no direct consequence to their joy, or their lives.

BOSWORTH: Going through the motions.

MILLER: Going through the motions. Exactly . . . exactly!

BOSWORTH: But you said you had a magical upbringing from your family. Is that where your artistic desires were born?

I feel like a sickness and dystrophy is growing in people, like people are getting sicker, something about our society, something about our psychological structures. We’re not whole.Ezra Miller

MILLER: Absolutely! My mother is an artist through and through. She’s a modern dancer. And I think the way she raised her children was with a playful, curious inquiry into the world. I remember going on hikes and she’d nominate a child as “leaf leader,” and that person would be in charge of pointing out to the rest of the group all of the beautiful and amazing and interesting and strange things happening in the world on our hike.

BOSWORTH: The older I get and the closer I get to being a parent, the more I realize it’s tough. And I really respect my parents more and more and the way that they took the time, like your parents, to find the magic in the world.

MILLER: Yeah, it might be that the most important thing is actually, yeah, raising up children with a true and lasting burning sense of curiosity. I don’t even know how they did it, or how they do it. Good parents are a marvel.

BOSWORTH: You play two roles where a child is incredibly affected by parenting—first in We Need to Talk About Kevin.

MILLER: Yeah, that’s an entire meditation on what can really go wrong, and the way in which parenting, especially mothering, is a primordial wound. I mean, really. When you birth a child, it’s like a bloody giving of self to the creation of a life. And basically, Kevin explores a mother who held within herself a deep resentment of the child. We see Kevin over the course of his life become more and more of a monster. And her resentment grows stronger until there’s this explosion of rage and they’re at war. That performance was entirely about finding all of the anger and the resentment inherent to mother and child. It’s just a scary truth. And it’s a very old story that’s entirely under-told. It’s too dark. Too dirty.

BOSWORTH: You’re not afraid of the dark spots as an artist?

MILLER: No! That’s what I yearn for. It’s what I want. I feel like a sickness and dystrophy is growing in people, like people are getting sicker, something about our society, something about our psychological structures. We’re not whole.

BOSWORTH: Is there anyone, or any part, that you’re desperate to play? You know, if the canvas was yours?

MILLER: I always thought it would be really, really cool to play Edgar Allan Poe, because when I was a kid, he was one of the authors who really blew my mind open to all sorts of weird dark and twisted places. When I can grow a moustache, I want to play Edgar Allan Poe.

BOSWORTH: What’s your biggest fear?

MILLER: Being invalidated by the people in my life. You see sometimes it’ll happen to people, that their self will stop coming through. And people will just cease to understand them. Getting lost in human perception is a very scary idea.

BOSWORTH: But that won’t happen to you. Because if I ever saw you sort of heading down that . . . You can just trust in the fact that I will smack you around a little bit. [laughs]

MILLER: You’d beat me up! These are the friends that I value most: people who would essentially use physical violence against me at a time when I seem to be teetering on the edge.

BOSWORTH: [laughs] So, in our film Another Happy Day, how did you prepare for Elliot? He’s a very angry human being.

MILLER: I started looking at doom, all around, seeing interlocking webs of connection between people that were gross and based on power dynamics.

BOSWORTH: Did that change you as a person?

MILLER: Well, yeah, you start feeling some of the physical effects, the shoulders start hunching a little and there’s a tension in the body and a sinking feeling in the pit of the stomach. Fear starts cropping up far more . . . Then I stopped sleeping, which is an important aspect, that Elliot’s brain is going fast and he’s not in a space as a human being where he can comfortably close his eyes. And that’s something very specific that I, as a human being, love—sleeping.

BOSWORTH: I know that you also play music. Does it feel like equal love for music and acting?

MILLER: I tend to not see a separation. I’m trying to have a life filled with wonder, and there are times I take to inhale just the world and all these wonderful people around me, and then the other thing I do is these exhales, and whether it’s an album or a film or whatever it is, it just feels right. [exhales]

BOSWORTH: Did that just feel like a therapy session?

MILLER: Yeah, kind of! We just talked about many things in a short period of time. Very chaotic, slash, cathartic experience. Thank you, Kate. You’re the beast’s feet.

Kate Bosworth is an actress whose upcoming films include Another Happy day and Straw Dogs.