Dennis Hopper Complete Interview

Part I

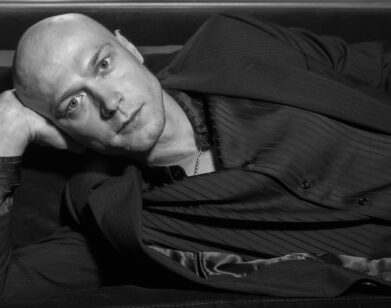

It makes perfect sense that Dennis Hopper was related to Daniel Boone. Like the notorious frontiersman, Hopper ascended into the mythic golden landscape of American culture. He might have been one of the most authentic representations of combustible cool that Hollywood ever managed to capture on film. Along with a handful of his co-stars throughout his career—James Dean, Marlon Brando, Peter Fonda, Jack Nicholson, and Sean Penn among them—Hopper came to embody a radical individualism, a tough masculinity, a dangerous sensitivity, and a shamanlike ability to move between worlds and fracture cultural codes. Which is why his death on May 29 at age 74, after a decade-long battle with prostate cancer, has resonated with so many so profoundly both within the spheres of film and art in which he moved for more than a half-century, and beyond them.

Hopper was born and raised in Dust Bowl–era Kansas and came to Hollywood from San Diego, where he had been working in a theater and doing Shakespeare, when he was just 18 years old. He made his first serious mark alongside James Dean, Natalie Wood, and Sal Mineo in Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955), but the truth is that Hopper himself was such an indelible character that the film industry—which has, does, and always will like its actors to fit into a box— often had difficulty knowing how to utilize him (or even, at times, what to make of him). Still, Hopper worked with both an older generation of classic Hollywood filmmakers (Henry Hathaway, George Stevens, John Sturges), and the next wave of insurgent, decidedly un-Hollywood ones (Francis Ford Coppola, David Lynch, Andy Warhol). Remarkably, the actor who appeared in movies such as Giant (1956), Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), Apocalypse Now (1979), and Blue Velvet (1986), who directed Easy Rider (1969), who had been working in and around Hollywood for nearly six decades, just received a star on the Walk of Fame this past March—a much-belated tribute for a man whose work in film has been nothing short of defining.

Now, recognition of the extraordinary body of work that Hopper has left behind is pouring in from every corner. On July 11, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art unveils Dennis Hopper Double Standard, the first comprehensive retrospective in the U.S. of Hopper’s work as a visual artist. The exhibition, which was planned before Hopper’s death, was curated by his close friend, Julian Schnabel—whose work on the show was a very personal project—and covers the entire span of Hopper’s career, including his film work, his paintings (often associated with the work of Semina, a loose group of West Coast artists), his black-and-white photography, projects, and his sculpture and assemblage pieces.

In the first of our own two-part retrospective of Hopper’s life and work, Interview’s chairman Peter M. Brant, who knew Hopper for more than 40 years, and gallerist Tony Shafrazi, who first met Hopper in London in 1963—and who represents Hopper as an artist and was integral to initiating and coordinating the MOCA show with the museum’s new director, Jeffrey Deitch—sat down with Hopper shortly before his death at Shafrazi’s gallery in Chelsea for a wide-ranging conversation about the ups and downs and prizes and punches of his one-of-a-kind, mind-bending journey.

PETER M. BRANT: Let’s start in the beginning. I know you were born in Kansas.

DENNIS HOPPER: I was born in Dodge City, Kansas, in 1936. It was just at the end of the Dust Bowl. We lived about seven miles outside of Dodge on a little 12-acre farm where we grew Chinese elm trees and had 400 chickens and cows and made all our own food. My grandparents were from Kentucky—I’m related to Daniel Boone. He was my great-great-great uncle. Sarah Boone, his sister, was my great-great-great grandmother. He only brought seven families into Kentucky, so he’s my great-great-great uncle three times—and not because he was three times away, but because there are first cousins who married first cousins, and he tried to hit some bad ones in the head and, you know, get rid of them, but he missed my side of the family. [laughs] So I was born in Dodge City, and then my father was in World War II. He was in the Office of Strategic Services—which was a precursor to the CIA—and served in China, Burma, and India. He came back from the war when I was about 9 years old, and we moved to Kansas City. But I think my brother’s bronchial asthma was just an excuse to move us to San Diego anyway.

BRANT: When did you move to San Diego?

HOPPER: When I was about 14. I saw my first mountain. I saw the ocean for the first time. I remember thinking that that ocean looked very similar to our wheat fields. I didn’t know what I thought I would see when I looked out at the ocean, but I thought I’d see something different. But then, looking out at the ocean, it was the same perspective I had looking out at a wheat field.

BRANT: When you were living in Kansas City, didn’t you take some art courses at the museum?

HOPPER: Oh, yeah. I would go to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art on Saturdays. I did that for three and a half years.

BRANT: [Regional American painter] Thomas Hart Benton was there?

HOPPER: Thomas Hart Benton would come in occasionally. He came about three times probably, just to visit the kids. But he wasn’t teaching, really. He would just walk through the museum. I’d study with his Rocky Mountain watercolors when I was a kid. I also used to have to wear a gas mask to school when I was a kid because of the dust. I would tell people that the first light I saw was in a movie theater, because the sun was just a little glow. I just really wanted to know where the trains were going, how to get out of Dodge. But my mother put me in a tap-dancing class with a bunch of girls, man. I had to wear this little white outfit. She was trying to live in another place in another time, but I couldn’t do it. I said, “I’m not going anymore.” So she got me these watercolors, and I learned to do this little mountain and the tree with the roots and the water coming by. So one day, Thomas Hart Benton came by and looked at what I was painting and said, “You’re little”—I think I was 11 years old at the time—“so you might be too young to understand what I’m about to say to you, but you’re going to have to get tight and paint loose.”

BRANT: Was your mom primarily the one who looked after your education and brought you to museums and got you to take courses, or were both your parents involved?

HOPPER: Well, my father was pretty busy. I mean, I learned more about him at his funeral than I did, really, growing up. He ended up managing the San Diego post office—which is really probably why we went to San Diego. But it was my mother, basically, who took care of those things—even though we had a terrible relationship, my mother and I. I mean, she screamed, yelled, and threw things at me. It was a terrible, terrible relationship. I wanted to be an actor. I decided when I was very young, when I first saw movies, that I wanted to be an actor.

BRANT: You were involved in a theater company in San Diego, weren’t you?

HOPPER: I was. I was at the Old Globe Theatre. When I was at Nelson-Atkins back in Kansas City, we’dbe there for five hours on a Saturday, but we would have an hour to go around the museum. They had a theater in the museum, and during my hour, I used to go in and sketch the actors. So I startedacting when we moved to San Diego at the Old GlobeTheatre in Balboa Park. The first play I did was [Charles] Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. I played the urchin who comes at the beginning asking for alms and gets run out. At the end, he gets a turkey. So I had to sit from the first act to the last act. [laughs] But I got through it. And then I started playing Shakespeare during the summer. They’d bring over English directors because the Old Globe in San Diego was a duplicate of Shakespeare’s Globe in England, which had burned down. The one in San Diego wasa duplicate they made for the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935. But I worked with some really good English directors. I worked with these guys from time to time during the summer, because you really had to be in college to do that, but there were a lot of parts that they let me play.

BRANT: What do you consider your big break in terms of getting parts?

HOPPER: Well, when I was about 16, I got a job working as an apprentice at La Jolla Playhouse. I worked for a guy named Hank Milam. Hank lived in the guesthouse at Vincent and Mary Price’s house near Beverly Hills—he did interior design. Hank was my boss, so I cleaned toilets, cleaned dressing rooms. And Vincent Price had actors over all the time, so I’d pick them up and drive them. But [actress] Susan Kohner, [agent] Paul Kohner’s daughter, was the other apprentice. We were around the same age, and they’d let us do backstage stuff until finally they gave me a couple of walk-ons.

BRANT: I remember Vincent Price was on The $64,000 Challenge.

HOPPER: Right, with [actor] Edward G. Robinson. The two heavies. [laughs] They tied each other in art for the top prize on that show.

BRANT: Vincent Price was a great art collector. Was that your first introduction to contemporary art?

HOPPER: Oh, absolutely. Vincent was a Yale graduate, I think, in art history. I’d come in and see a Franz Kline, a Jackson Pollock. Emerson Woelffer was doing these great bird abstractions at that time. Richard Diebenkorn, I just fell in love with.

You can’t have preconceived ideas. You have to live in the moment. You have to keep yourself open.Dennis Hopper

TONY SHAFRAZI: Now, this is in the mid-1950s you’re talking about.

HOPPER: This is 1954. So I’ve now done my summer working at La Jolla Playhouse, and I’m playing Lorenzo in The Merchant of Venice. Through Vincent, I met John Swope, who I think Vincent knew through the University Players. John was a terrific Life magazine photographer—he did this great picture of Marlon Brando as Mark Antony. So I asked John Swope if he and his wife Dorothy McGuire [the actress who co-founded the La Jolla Playhouse] would come and see the performance. Then I made an appointment to come see John, and he wrote me a letter of introduction to Ruth Burch, who was a casting director at Hal Roach Studios, where they made two-reelers—like Laurel & Hardymovies and those kinds of things. So I had the letter, but then John went to Europe, and I couldn’t get in contact with him. For six months, I tried to get in to see Ruth Burch, but I couldn’t get in without an agent or a Screen Actors Guild card. It was a catch-22 beyond any. So finally I was with my friend Billy Dwyer, who was a singer. We’d gone to high school together, and he was going to these dance classes. There was an agency next door run by a woman named Helen Ainsworth. I didn’t know what I was going to say to her—she was a funny lady. But she was a powerful agent and producer at the time. So Billy was in taking a lesson, and I walked into the agency and showed them my letter. There was a young agent there named Robert Raison, and he said, “Let me see that.” He looked at the letter and then he said, “Can you do anything?” So I did one of my dramatic declarations that I had done in high school, and it flipped him out. He got me in to see Ruth Burch, who gave me a 10-line part in Cavalcade of America as a Civil War amputee who is dying, and I got my Screen Actors Guild card. It cost about $200, and I didn’t have the money, so I borrowed it from the agency. Then I went back to San Diego to work and earn the money to pay them back. I got a job going door-to-door, asking people for their old phone books so I could give them new ones. I wore a little suit that I bought at Sears & Roebuck. But out of all San Diego, the area I get is Lemon Grove—where I live! There was a lot of, “Oh, Hopper’s here. He’s asking for the phone book?” [laughs] So it was a little embarrassing, but I paid back the agency. But before I went to San Diego, I got this part on the series Medic that I had read for.

SHAFRAZI: That’s the episode “Boy in the Storm”?

HOPPER: Yeah. When I read for it, there were, like, 40 guys trying out for the part.

SHAFRAZI: The part was basically a young boy who is epileptic, right?

HOPPER: Yeah, epileptic. It aired on January 3, 1955. Seven studios called right after and wanted to put me under contract. The first one that called was Columbia Pictures. The head of Columbia at that time was Harry Cohn. So Raison and I walk into the studio, and at the end of this long hallway—I mean, everything was psychological with Cohn—he had this long, narrow office. You had to walk forever to get to this big desk at the end of the room. He had a rainbow of Academy Awards behind him. And sitting at the desk with us is Abe Schneider, whose son, Bert Schneider, eventually gave me the money to make Easy Rider. Abe was second in charge and eventually became the head of Columbia. So Harry Cohn is sitting there, smoking a cigar. He’s like, “Come on in, kid!” And I walk, swish, swish—you know, sweating, man. I mean, I’ve never been inside a studio before, never seen an Academy Award! So Cohn sits me down and says, “I saw you last night. You’re the most naturalistic actor I’ve seen since Montgomery Clift,” and blah blah blah. He says, “We’re going to make a big star out of you. What have you been doing, kid?” So I tell him, “Well, I’ve been doing Shakespeare in San Diego.” And he says, “Shakespeare? Oh, god, not Shakespeare! Shakespeare ruins movie actors!” So he turns to Max Arnow, who was his casting director. “Max, get him some numbers and send him to school!” I said, “What the fuck are you talking about? You’re telling me I have to go to fucking school to learn how to be a movie actor?” I mean, that was just it—I told him to fuck himself, basically. So I was banned from the studio. I was kicked out of the studio right then. I was escorted out the door, man. My whole agency was banned. [laughs] I wasn’t allowed to come back until after I made Easy Rider and I edited it for a year at Columbia. But by then Harry had died and Abe had taken over the studio.

SHAFRAZI: How did you get Rebel Without a Cause?

HOPPER: After Columbia, I went in to see Warner Bros., which was the second studio to call. The casting people there said, “If you to go see Nick Ray and he puts you in Rebel Without a Cause, then we’ll put you under contract with the possibility of you playing the son in Giant.” Which is what I wanted. I went to see Nick Ray, and he said, “Yeah, you can be in it.” Then I went to see East of Eden [1955], because it was the only movie that James Dean had made at that point.

SHAFRAZI: Elia Kazan directed it.

HOPPER: Yeah. It had just been released a couple of weeks before.

BRANT: So in 1955 Nick Ray shoots Rebel Without a Cause.

HOPPER: And then we go right into Giant, and Dean dies.

BRANT: When you were shooting Rebel Without a Cause, weren’t you at that point sort of paired up a little bit with Natalie Wood?

HOPPER: Oh, a little bit. [laughs]

BRANT: You were kind of seeing her. . . .

HOPPER: Oh, we were having a big fling. A big fling. We were of like mind that the generation before us had had a lot more fun and was more outrageous than we could ever be. But we did try. And [Rebel Without a Cause actor] Nick Adams and Natalie and I—we were really close.

SHAFRAZI: Didn’t you have an accident with Natalie? You were on your motorbike.

HOPPER: No, it was not a bike. It was in a car. It was with her and her girlfriend, just before we shot Rebel. Actually, Natalie didn’t have the part yet. But she was going to get it.

BRANT: She was pretty close with Nick Ray as well. [laughs]

HOPPER: Well, right, exactly. Jimmy was in New York, so Nick had me test with all the girls. We tested every young starlet in Hollywood for that part. We tested Jayne Mansfield. But Natalie happened to be one of them. So I tested with her. At the time, I was living in this little apartment with Bill Dwyer. The next day, the phone rings. It’s Natalie, but I don’t know who she is. Bill does, though—he says, “It’s Natalie Wood! I think you tested with her.” But I can’t remember because I tested with 20 girls. So I get on the phone, and she says, “I tested with you last night. Do you remember? It was raining.” I went, “Oh, yeah, yeah.” And she said, “I’d like to fuck you, but I don’t do anything. I just lay there.” [laughs] And I said, “Uh . . .” Nobody had ever—or has since—said that to me. So she said, “I have to do a little rehearsing with Nick [Ray] at the Chateau [Marmont], but if you pick me up afterward. . . .” So I went to pick her up. She gets in the car, and I said, “You know, I’ve got a roommate. . . .” She says, “Let’s just go up the hill. I know a lover’s lane.” So she took me up the hill, and we started linking up, and I started to go down on her, and she said, “Oh, you can’t do that.” I said, “Why?” She said, “Because Nick [Ray] just fucked me.” [all laugh]

BRANT: At that point, you were really good friends with Nick Adams.

HOPPER: Yeah.

BRANT: Did you live together?

HOPPER: We did. We took a place up in the mountains together.

BRANT: I’d always heard that when Elvis Presley was doing films in L.A., you knew him, as well.

HOPPER: That was a little bit later. Nick was very close with Elvis. He met him through me. Nick was on the phone all day with [director and producer] Mervyn LeRoy and various people. He was working it while I was just reading An Actor Prepares. Nick was really interesting. His real name was Nicholas Adamschock. Him and Jack Palance and Charles Bronson—they were all from the same sort of coal-mining Pennsylvania background where they had these long eastern or northern European last names, which they changed.

SHAFRAZI: So Rebel Without a Cause comes out, and it’s an immediate success, right?

HOPPER: Well, Dean died before its release. Most people get that confused. The only picture he had released at that point was East of Eden, which was not as successful. So when we got to Texas to film Giant, nobody knew who James Dean was. They’d never really seen him in anything. They just thought he was a weird guy. [laughs]

BRANT: It’s funny that you shot Giant in Marfa, which becomes this big art community a few years later.

HOPPER: It was really interesting. The Texas laws for drinking at that time were that you had to go into an establishment that had alcohol, which was usually a private club or a country club, and you had to buy the whole bottle—I think they thought if you bought the whole bottle, then you wouldn’t drink as much, right? [laughs] So one night, we drove from Marfa to Alpine, which is about 25 miles—not that far—because we wanted to drink, and Alpine had a country club. Jimmy was there, and this guy came up to us and said, “You actors!” He did this whole rag on Jimmy—I mean, real bad. He didn’t know who Jimmy was. He just knew he was in a movie. So Jimmy didn’t do anything, and we got up and left. But the next night we’re back there, and this same guy turns up and he’s worshipping Dean. So we thought, This is an opportunity to get him back. But Dean didn’t do anything. I asked him later, “Why didn’t you wail on this guy?” He was like, “It’s not necessary,” and left it at that. But there was no real public awareness of Jimmy until after Rebel Without a Cause came out. Jimmy dies two weeks before we finish shooting Giant, and then Warner Bros. sends Natalie, Nick, and I out to promote Rebel Without a Cause and everything goes through the roof.

I got my Screen Actors Guild card. It cost about $200, and I didn’t have the money, so I borrowed it from the agency. . . . I got a job going door-to-door, asking people for their old phone books so I could give them new ones.Dennis Hopper

SHAFRAZI: How did you first meet James Dean?

HOPPER: I was walking down a hallway at Warner’s. I was on my way back to Nick’s office with my agent, Robert Raison. You’ve got to understand, Hollywood, at this time, was all suits and ties. These guys were old-school gentlemen. They smoked cigars, but they were gentlemen. Suddenly I see this guy walking toward me in a turtleneck and dirty Levi’s. He looked like he had five days’ growth, and his hair was all messed up. As we walked by, my agent said, “That’s James Dean.” I’d just seen him in East of Eden, but I didn’t even recognize him. So I had my meeting with Nick, and then I went to the drugstore across the street from Warner’s, and Dean was sitting at the counter. He had a cup of coffee and sugar, and he was pouring the sugar on the spoon until it got to be heaping, and then he would watch it dissolve in the coffee, and then he’d pour another one. He was doing this over and over. He wasn’t talking to anybody. Raison said, “Let me introduce you.” So we went up, and he said, “Jimmy, this is Dennis Hopper. He’s going to be in the movie with you.” But Dean never stopped. Never looked around.

SHAFRAZI: He kept pouring the sugar.

HOPPER: He just kept pouring the sugar and letting it dissolve in the cup. But here’s what was really important, which has taken me a long time to digest: I had never seen anyone improvise before. I really did think at that point that I was the best young actor in the world. And then I’m on set, and the first thing we’re doing is the scene in Rebel at the police station, where he gets arrested. And suddenly, Dean starts making siren sounds. When they search him, he starts to laugh because it’s tickling him, and I’m thinking, “Where the hell is this on the page? Where is this coming from, man?” I’d never seen anyone improvise before. Because I was a Shakespearean actor, I had preconceived ideas, line readings—everything was a gesture, everything was conscious.

BRANT: It was disciplined.

HOPPER: Yeah. But in Method acting, you can’t have preconceived ideas. You have to live in the moment. You have to keep yourself open. I was totally on the other side of the track. In point of fact, Harry Cohn did have something to say. [laughs]

BRANT: I remember you telling me a story about filming a scene with Dean and Elizabeth Taylor when you were making Giant.

HOPPER: We were working on Giant, and we’re out in the middle of Texas. It was a scene that takes place just before Dean discovers oil on his land, where Elizabeth Taylor comes by and he makes tea for her. It’s the first time Dean has ever acted with her. But even though we’re out in the desert in Marfa, there are a thousand people watching us film behind a rope. It’s a scene where Dean has a rifle on his back. He brings her in and makes her tea, and then, suddenly, he stops. And he walks a couple hundred feet away to where these people are watching us, and in front of all of them, he pulls out his dick and pisses.

SHAFRAZI: In front of them?

HOPPER: Facing them, with his back to the set. Then he comes back in and does the scene. So, later, we’re driving back to Marfa, and I said, “Jimmy, I’ve seen you do a lot of strange things, man, but you really did it today. What was that all about?” He said, “It was Elizabeth Taylor. I can’t get over my farm-boy upbringing. I was so nervous that I couldn’t speak. I had to pee, and I was trying to use that, but it wasn’t working. So I thought that if I could go pee in front of all those people, I would be able to work with her.” [all laugh]

BRANT: That’s great.

HOPPER: That’s what it was, though, with Dean—it really was all about the work. There’s that scene in Rebel where we go on the chickie run, where Buzz, who was played by Corey Allen, goes off the cliff and dies. Warner Bros. had come down on me because Nick Ray was getting caught having an affair with Natalie, and so he blamed it on me. I went out to fight Nick Ray, and Nick said, “Someday you’re going to have to learn how to use your mind rather than your fists.” So I walked away from that one. Then I see Dean and I grab him and throw him in the car. I said, “I thought I was the best young actor in the world, but there’s no question that you are.” Then he asked me a lot of personal questions. He asked me about my family, where I was from, what my feelings were. He told me what his feelings were about his, and they matched in a strange way. His mother died when he was very young, and she was the one who encouraged him and told him that he was a genius. His father stayed in California and sent him to live with an uncle in Indiana. So he used to go to his mother’s grave and cry, and that turned into a kind of hate, and he started pounding on things and saying, “Why did you leave me?” And that became the energy that he used to fulfill what she wanted for him. So he told me that, and I said, “Well, should I go study?” And he said, “No, you’re too sensitive. It’ll destroy you. What you need to do is start living in the moment. You’ve got to live moment to moment.

Reality doesn’t have any preconceived ideas. You’ve got to learn how to smoke the cigarette, not act smoking the cigarette. You need to drink the drink, not act drinking the drink. You’ve got to do things and not show them.” He says all of this in the car.

SHAFRAZI: You’ve said that, in a way, Dean half-directed Rebel.

HOPPER: He didn’t half-direct it. I always thought he did direct Rebel. I mean, Dean would set the camera. He’d rehearse the scene. Isn’t that what a director does?

BRANT: And Ray would let Dean do it?

HOPPER: Yeah, because very honestly, Dean was correct. If what Dean wanted to do was intelligent, then Nick Ray would let him do it.

SHAFRAZI: Ray was really a remarkable director of a new kind, quite different from the old school, even though he’d done some great things and continued to do great things. He was very sensitive to James Dean.

HOPPER: Well, Nick Ray had worked [as an assistant] for Elia Kazan, so he came out of Kazan’s way of working. He was a great admirer. Nick Ray was intelligent enough to let Dean do what he did. You know, it’s one thing to think you’re the director and you have to get involved with everything, but when the fuckin’ thing is working, you have to have that ability to step back and let it work.

BRANT: Then you worked with one of the great American directors, George Stevens, on Giant. That must have been a whole other thing from Nick Ray.

HOPPER: That was a whole other thing. George started out doing two-reelers. He actually started out doing camera, so Dean wasn’t going to be setting any cameras for him. He and Dean fought like dogs. Then he got on me, too, because everything that Dean did was somehow my fault.

BRANT: Did you have respect for Stevens at the time? He had done Shane [1953] and all these great films.

HOPPER: Oh, absolutely. I had the most respect for him. Always did. His arguments were not wrong.

SHAFRAZI: So as you finish Rebel, of course, you’re already getting very close with Jimmy.

HOPPER: Dean and I had a teacher-pupil relationship. He was [five years] older than I was. I mean, we’d see each other at [film producer] Arthur Loew Jr.’s house, with Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, and [Rebel Without A Cause screenwriter] Stewart Stern. These were people we hung out with three days a week. We’d play games. We’d even play boarding house. And Dean would be there. But I wouldn’t go out on dates with him or whatever. Our relationship was about acting.

BRANT: He was pretty much a loner, wasn’t he?

HOPPER: Well, Dean had girlfriends. He was in love with Ursula Andress. He was in love with Pier Angeli. He had all of these love affairs going on that were going bad, and he was taking care of that. But we saw each other at the studio every day.

BRANT: But then something happens when Dean dies.

HOPPER: Whew, yeah. Well, first of all, he was going to direct movies. Henry Ginsberg, who co-produced Giant, was going to produce Dean’s first movie. It was called The Actor. Obviously, he was going to change it because the book was not very good. But he was going to direct. And he was going to act in The Left Handed Gun [1958]with Arthur Penn and Somebody Up There Likes Me [1956], which was about Rocky Graziano.

SHAFRAZI: In 1955, you and James Dean do two movies. And then that same year, you go to a small gallery together. [The late curator and gallerist] Walter Hopps remembered you bringing Dean to this new gallery.

HOPPER: Actually, Dean brought me. It was called Stone Brothers Printers. There was this Chinese guy on Hollywood Boulevard who dressed in a Confederate general’s outfit. Could barely speak English, but he did Shakespeare in front of the Chinese Theater. He was a street performer. Dean thought he was great. So he was going to have this guy do a reading at Stone Brothers Printers. Walter Hopps, Ed Kienholz, Wallace Berman, George Herms, [poet] Bob Alexander—that’s where we met all those guys. After Dean died, I just started hanging out with them.

Suddenly I see this guy walking toward me in a turtleneck and dirty Levi’s. He looked like he had five days’ growth and his hair was all messed up. As we walked by, my agent said, ‘That’s James Dean.’Dennis Hopper

BRANT: And then Walter Hopps opens Ferus Gallery [with Kienholz and Alexander] in ’57.

HOPPER: And [art dealer and gallerist] Irving Blum walks into Ferus and sees a group show, and Walter has no money, so they become partners.

SHAFRAZI: Dean’s death froze everyone. How did it affect you?

HOPPER: Before Jimmy had gone up to race his car, I think he had gone into this silent-order monastery down in Malibu and spent three days up there. When he came back, he came to the studio. And it was one of the few times I ever saw him dressed in a suit and tie. It was as if he was saying goodbye to people. He was going to race. But he was going to come back. George Stevens wouldn’t let him race when we were making Giant, which was obviously intelligent, but Dean only had two weeks to go, so Stevens said okay. Dean spent all of his money on this Porsche Spyder. He was actually going up to where they shot East of Eden to have a race. It was not his fault. I mean, this guy came and didn’t see him. Dean had gotten a ticket for speeding that afternoon, so he wasn’t speeding when it happened. Rolf [Wüetherich], the guy who was with him, lived.

SHAFRAZI: And Dean had just shot a clip about safe driving, which is remarkable.

BRANT: What was your reaction when you found out that he’d died?

HOPPER: Okay, so I’m in the theater in Santa Monica. My agent is there. The play hasn’t started yet when my agent gets up and leaves to take a call. I’m sitting there, and he comes back and he’s ashen. He says, “I have to tell you something, but promise me that you’ll stay here in the theater.” I said, “Is it someone in my family?” He said, “No, but are you going to stay here?” “Yeah,” I say. He says, “James Dean was just killed in a car accident.” And at that moment, the lights went out on the stage, and the spotlight came up on this empty chair, and I flipped out. That was it. In fact, I think I hit my agent. I went crazy. It was a bad time. You know, I really believe in destiny, and that didn’t fit in.

BRANT: So when Dean passes, you’re a young actor, and you’re going through what has to have been, emotionally, a big change in our life: hitting stardom, landing major roles, everybody watching you. What were you going through at that time?

HOPPER: Well, people in Hollywood either loved Jimmy Dean or they hated him—but the people who loved him went into this whole thing where they were having séances, where they were seeing him, where they were talking to him. But I just couldn’t grasp the fact that he was dead. He was going to direct movies. He was the most incredible actor I’d ever seen. And the idea of destiny . . . I was really confused. Warner Bros. had loaned me out to 20th Century Fox to do this film, From Hell to Texas [1958], with [director] Henry Hathaway. But I just didn’t want to do the movie. I didn’t like the part, and I thought, after Giant, I should be doing something else. Hathaway was one of those tough old-school directors. He became a prop man, and worked his way all the way up to becoming a director. He was a real workhorse—and a big filmmaker. He wanted me. He thought that I was the best young actor he’d seen. But he wanted me to imitate Marlon Brando. He gave me gestures, line readings—all these preconceived things. And I refused to do them. I walked off that picture three times on location—and three times, he came to get me. We’d have dinner. He was the most charming man you’d ever meet at dinner. But in the daytime, he was a monster. So at dinner we’d talk about what we were going to do the next day, and he would say, “Great, terrific.” And then we’d get on the set, and he would be like, [raises voice] “That’s fuckin’ dinner talk, kid!” So we finally get back to the 20th Century Fox lot, and it’s my last day on the picture. I come into the studio and Hathaway is there. He points to a stack of film cans and says, “You see what that is over there?” I say, “It looks like some film cans to me, Henry.” He says, “Yeah. We’ve got enough to shoot for three or four months. You see what we got over there?” He points to a bunch of sleeping bags. “We’ve got sleeping bags. We’re going to sleep here on the soundstage until you do the scene my way.” So we start working at around 7 A.M., and we send for lunch at around 11 A.M. when Steve Trilling, who was second in charge to Jack Warner at Warner Bros., calls. He says, “What the hell is going on over there? Do you know that Hathaway owns 40 percent of 20th Century Fox? What are you trying to do, lose our studio? He’s going to sue us! Just do what he says and get your ass back home.” And then lunch arrives, and Jack Warner calls. “Are you out of your fuckin’ mind?” he says. “Hathaway is going to own Warner Bros.! Whatever he wants, do it a hundred times for him.” So, finally, it’s 11 o’clock at night, and I’ve tried every way possible to do the scene, and I finally just break down and start crying. I say, “Okay, just tell me what you want.” And he gives me all of this stuff to do, and I do it, he prints it, we’re done, and I leave the studio. I didn’t really work again in film after that until Hathaway rehired me for The Sons of Katie Elder [1965].

BRANT: How did that happen?

HOPPER: Well, I came to New York to study with Lee Strasberg for five years, which turned out to be really good for me because then I was connected in New York. But I wasn’t thinking that way at the time. I couldn’t work in film after the Hathaway thing, so I was thinking that the thing I could do was work in television.

BRANT: How was it viewed at that time to work in television? You did so many big series. You did episodes of The Twilight Zone, The Rifleman, Bonanza.

HOPPER: Well, Warner Bros. got into television very early, so I did a lot of television there. In the beginning, it was sort of okay to do television. But then it became this thing where movie actors didn’t do television—they certainly didn’t do commercials, because that just meant the end of your career.

Peter [Fonda] said, ‘Let’s promise ourselves that we will not do a motorcycle movie.’ I said, ‘Absolutely, man. We’re going to be like the singing cowboys. I’m going to be the sidekick, and this is going to be ridiculous.’ Dennis Hopper

BRANT: A lot of the shows you did were Westerns.

HOPPER: A lot of them were Westerns—Rifleman, Wagon Train, Cheyenne.

BRANT: After Giant came a period where the Western becomes a really big factor in our culture. You were in one of my favorites, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

HOPPER: Oh, yeah. John Sturges.

BRANT: What was it like working with Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster on that film?

HOPPER: It was great. I mean, the stuntmen on that film also worked on John Wayne’s pictures. They were just a fun group, man. I was the rookie. I got every game played on me. I was actually closer to Douglas because he was a little more fun. One of the tricks they played on me involved a gunfight. We’re out doing the actual gunfight at the corral—we’re shooting and stuff—and there’s a crowd watching, including this young girl who I’d been having a fling with. So they came up to me and said, “The police are here to arrest you because you had an affair with that girl. Just stay with us. They can’t come into the scene because we’re all shooting guns and everything, so stay in the scene.” I went, “Oh, I don’t know. I guess she’s pregnant.” So the guys take me out of the scene like I’ve been hurt, and they get me into my room at the hotel, and this carried on for four days before I was like, “Come on! There’s no police.” [laughs] They’d come in and say things like, “The girl’s trying to get away!” I mean, it was just one thing after another.

BRANT: So what happened after you went to New York?

HOPPER: So then the first job I get after five years is when [director] Stuart Rosenberg calls me in to read for The Twilight Zone.

BRANT: Is that the episode where you play the Nazi?

HOPPER: Yeah. [Twilight Zone creator and producer] Rod Serling was still alive at the time, which was really cool. Rosenberg was the best in television at that time, and I quickly became one of his players. I did two episodes of The Defenders and an episode of Naked City before he took me to England to star with Patricia Neal in an episode of Espionage. Then he made Cool Hand Luke [1967], and he took all of the guys who were on television shows and put them in there. I don’t even have one line in the movie.

BRANT: But your presence is felt.

HOPPER: This is the way Rosenberg explained the character. He said, “You’re not going to have any lines, but you’re going to be around all the time. It’s going to be like everybody takes care of your character because he’s like a child.”

BRANT: So how did Hathaway wind up hiring you again?

HOPPER: Well, I’d married my first wife, [actress] Brooke [Hayward] in 1961, and we’d had our daughter, Marin. . . .

BRANT: Brooke is like Hollywood royalty.

HOPPER: Hollywood royalty. Her father was [theatrical producer and agent] Leland Hayward and her mother was [actress] Margaret Sullavan. So Marin is about 4 or 5 months old when Hathaway calls me. Now, during this period of time when I wasn’t making movies, which I think was about eight years, I thought of every way possible to get back, whether it was killing Hathaway or just studying his films. And I realized by watching his movies that the reason he gives you all of these things to do in a scene, or tries to create some kind of anxious energy, is because he doesn’t like to move his camera. I don’t even know if he knows that, but in my mind, that’s what he’s doing. And because he doesn’t move it, he needs you to move in order to get some energy on the screen. So I come in and see him—I mean, I like the guy. It’s not that I dislike Hathaway.

BRANT: You just didn’t admire his work at that time.

HOPPER: I was trying to work in another way, and I couldn’t. So he calls me in and says, “Now we want you to play this part. Duke and I have decided this since you married a nice Irish girl, and we knew her mother.”

BRANT: Duke is John Wayne.

HOPPER: Yeah. He says, “We think, now that you have a daughter and you’re married, you should go back to work. But you should know, Wayne can’t stand this Method shit, so don’t do any of that.” I said, “Don’t worry, Mr. Hathaway. I’m a much better actor now than I was eight years ago.” So we go down to Durango, Mexico, and I’m doing this 10-line scene. It’s the first scene of the picture. So Wayne is there—he had one lung out already—and [producer] Hal Wallace is there. Hathaway gives me the line reading and every gesture he wants me to do, and I just do it, and he comes up to me. He’s got a cigar in his mouth, and he’s crying. He says, “That was great, kid. Great.” So I say, “You see, Mr. Hathaway? I’m a much better actor now that I was eight years ago.” And he says, “You ain’t a better actor, kid. You’re just smarter.”

BRANT: So as we get toward the end of the 1960s, you do Easy Rider.

HOPPER: Well, first I wrote The Last Movie with Stewart Stern, who wrote Rebel Without a Cause. Stewart wouldn’t do it unless I paid him. Because the way we worked, I would tell him what I wanted and he would go upstairs and write it. That was the way we did it. But at some point he said, “You’re going to have to pay me. It’s like going to a psychiatrist. If you want to tell me this story, you’re going to have to pay.”

BRANT: So what happened with it?

HOPPER: We wrote it, and I gave the screenplay to Peter Fonda, who read it and said, “I’ll produce this.” So we go all over town trying to get financing but can’t. We come to New York—we can’t get financing there, either. And then we went in to see Huntington Hartford.

BRANT: Whose family started A&P.

HOPPER: Yeah. I guess he’d been doing a lot of acid because he had somebody painting psychedelic stuff all over his apartment. It was totally crazy. So we get in there, and I’m explaining the film to him and asking him for money to make the movie, and he says, “You’re so passionate about this. I’ll tell you what: I’m going to give you the money.” And I’m like, “Wow.” But then he says, “All you have to do is levitate, right now, in front of me.” [all laugh] I said, “Fuck you. I’m out of here. I wouldn’t fuckin’ levitate in front of you if I could.” But anyway, nobody wanted to make The Last Movie. So then Peter and I went to work at American International Pictures, and Peter stars in The Wild Angels [1966].

SHAFRAZI: With Roger Corman.

HOPPER: Corman, right. And he becomes a big star from that. Everyone was at AIP [American International Pictures] back then—Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Brian de Palma. It was the only place you could go if you weren’t in the union, where they’d give you cameras and let you go out and shoot. They wouldn’t pay you, but if you were making a movie for them, you could go out and shoot on weekends. I did one called The Glory Stompers [1968]. But Peter and I were still trying to do a movie. He said, “Let’s promise ourselves that we will not do a motorcycle movie.” I said, “Absolutely, man. We’re going to be like the singing cowboys. I’m going to be the sidekick, and this is going to be ridiculous.” So Peter is out on the road promoting The Trip [1967]. He’s at the Toronto Film Festival, and he calls me up at three o’clock in the morning and says, “I just left Sam Arkoff”—who was one of the owners of AIP—“and James Nicholson,” who was the other owner and no relation to Jack. “I told him this story, and they said they’ll let us make a movie and you can direct.” Peter says, “Don’t get angry with me. Just listen: These two guys go over to Mexico on dirt bikes and smuggle back a bunch of marijuana. . . .” Well, you can’t take a lot of marijuana on a dirt bike, but okay. He continues, “They come back and sell the stuff and get these big, gleaming bikes and go cross-country to Mardi Gras. They’re going to retire in Florida, but they get shot by a couple of duck hunters. What do you think?” So I said, “Did they tell you they’d give you the money?” He said, “Yeah.” “And they’ll let me direct and act in it?” “Yeah.” So I said, “Sounds like a great fuckin’ idea to me.”

Part II

When Easy Rider came out in 1969, the times were changing for Dennis Hopper. Before writing, directing, and acting in his seminal road movie about a pair of cocaine dealers on a motorcycle trip across the fractured landscape of Vietnam War–era America, the talented but explosive Hopper—who broke out alongside James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955)—was still emerging from an involuntary Hollywood exile following his clash with the powerful director Henry Hathaway on the set of the 1958 western From Hell to Texas. But as the ’60s were staggering to an end amid a country divided by an unending war, the old studio system of moviemaking was crumbling. Easy Rider helped to emancipate American cinema from the tired Hollywood formulae, and the film’s iconic, psychedelic visions—the red-white-and-blue flag stitched onto the back of Peter Fonda’s black leather jacket might as well have been put there by Jasper Johns—served as the travel poster for the new, free-spirited American rebel. Hopper literally roared his way into the ’70s, courtesy of a Harley-Davidson chopper and a zeitgeisty movie tagline: “A man went looking for America. And couldn’t find it anywhere . . .”

With Easy Rider, Hopper not only evolved into a writer and director, but also a powerful character actor—a track on which he would continue throughout his career in such wide-ranging roles as the gentle drunk in Rumble Fish (1983), the mad bomber in Speed (1994), the art dealer Bruno Bischofberger in Basquiat (1996), the doomed father in True Romance (1993), but never so unforgettably as his cameo in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) as a raving photojournalist-cum-mystic, and the psychopathic nightmare incarnate Frank Booth in Blue Velvet (1986).

Hopper possessed so much intensity—on screen and off—that he protested it was difficult to successfully pursue more than one craft at a time. He claimed to suffer from an artistic schizophrenia—in one life, Hopper was an an actor, director, and screenwriter; in the other, a photographer, painter, and sculptor. At the time, serious movie actors did not pursue careers as serious artists and vice versa. But in the 1960s, while he was blacklisted across studio lots, Hopper took a lot of photographs, including many well-known portraits of his famous Hollywood friends, and immersed himself in the already-exploded L.A. art scene of that era—populated by artists like Ed Ruscha, Robert Irwin, and Wallace Berman—brought about by the opening of Walter Hopps, Robert Alexander, and Ed Kienholz’s famous Ferus gallery in 1957. Hopper bought an early Warhol soup can painting for $75, instigating a lifelong relationship with the artist and a passion for collecting.

After the critical and commercial success of Easy Rider, Hopper became a commodity in Hollywood again. He was riding high at the time, as was his drug and alcohol intake. He was bankrolled by Universal to make The Last Movie, his trippy movie about the making of a movie. The drug-addled on-set spectacle of the shoot in the Peruvian Andes was seized upon by journalists, and the movie was a financial disaster. Years later, Hopper was still consuming seemingly inhuman quantities of booze and drugs when he re-emerged on the Philippines set of Apocalypse Now. He continued to struggle with his substance abuse problems through Out of the Blue (1980) and Rumble Fish, both movies in which he portrayed an alcoholic father, until he got clean in 1986. Though he still managed to channel his unhinged, chemically altered side in performances, particularly his frightening turn in Blue Velvet and as the alcoholic basketball coach in Hoosiers (1986), a part for which he earned an Oscar nomination.

Throughout the many cycles of his career, Hopper has been incredibly high and unreachably low, lost and found, actor and artist, father and husband, hero and outcast, revered by one generation and misunderstood by another. But whatever he was at a point in time, Dennis Hopper lived the hell out of that moment. Shortly before his death last May after a long battle with prostate cancer, Hopper sat down with Interview chairman Peter M. Brant and gallerist Tony Shafrazi, who represents him as an artist. They did so at Shafrazi’s gallery in Chelsea, on the west side of Manhattan. Here we present part II of their interview—a celebration of his remarkable career and even more remarkable life.

It actually wound up taking me a year to edit Easy Rider because I was going cross-country as we were making it and couldn’t see the footage. But I came back with 80 hours of film.Dennis Hopper

TONY SHAFRAZI: So, Dennis, as we come to the end of the ’60s, with you having just recently returned to making movies after a period where you weren’t working in film as much, you come to make Easy Rider—which, of course, goes on to become a major classic. But as you were going to make the film, it was against the backdrop of a very interesting time in America. The Vietnam War is exploding—there are demonstrations everywhere. The Democratic National Convention is happening in Chicago, and William S. Burroughs, Terry Southern, and Jean Genet have all been sent there to cover it for Esquire—and this is all happening just as you’re conceiving the film. Originally, Southern was supposed to write Easy Rider, right?

DENNIS HOPPER: He didn’t write anything. Peter [Fonda] and I just talked out the story as we walked around on his tennis court in L.A. for about two-and-a-half weeks. I’d asked Peter and Terry to write it because I didn’t want to write a screenplay. But I had a total outline, and I knew where the scenes had to be and how long they had to be.

PETER M. BRANT: What was the total budget for Easy Rider?

HOPPER: Around $340,000. [Production manager] Paul Lewis and I were going cross-country to find locations, and I’d sent Peter to New York to work with Terry on the screenplay because [executive producer] Bert Schneider was saying, “I’ve got to have a screenplay! I’ve got to show the producers a document. You don’t understand. Just trust me!” So as Paul and I were scouting locations, we discovered that Peter got the date wrong for Mardi Gras: He was two months off. It was actually only two weeks away! Now, everybody who has tried to make a movie at Mardi Gras—including Orson Welles—has failed miserably. And as we’re getting further and further into figuring out the film, I’m turning more and more into Henry Hathaway. I’m worse than Henry Hathaway because I’ve waited so long to direct a movie like this. But then I discovered that we only have two weeks, so even though we didn’t have a go-project yet, we rushed and got a bunch of friends together and went to shoot it in New Orleans on 16mm. The whole acid trip and all of the New Orleans stuff was all shot on 16mm over four days. I shot the entire movie in four-and-a-half weeks. So that’s how it started. It actually wound up taking me a year to edit Easy Rider because I was going cross-country as we were making it and couldn’t see the footage. But I came back with 80 hours of film.

SHAFRAZI: So the Mardi Gras sequence was the first thing that was shot.

HOPPER: Yeah, and everybody left me before the part in the cemetery, except a cameraman, a sound man, Peter, and the girls. So I shot that whole thing, the whole acid trip. It was raining that day . . . It’s beautiful. So then I came back from that trip and it turns out that Peter and [associate producer and brother of Hopper’s first wife, Brooke Hayward] Bill Hayward are recording me. Every time I turn around they’re filming me—and I’m not sure why—but I’m saying things like, “We’re going to win Cannes, man! We’re young! We’re going to take our energy and our strength and we’re going to take this thing all the way! Just trust me and do what I’m saying! Nobody shoot any film until I tell them to!” I mean, we were all in open fights with one another at the time, I didn’t find this out until Bert called me into his office after the movie was released, but Peter and Bill apparently wanted to pay him back the money he’d given us for Easy Rider and fire me. This is Peter and my brother-in-law, okay? This is before we’ve written a screenplay. So apparently they went in to see Bert and made him listen to everything they’d recorded of me, and Bert listened to it and sounded really excited. He said, “All I’m asking you guys to do is bring a red light, a green light, and a blue light, so you can make white light. They’ll all mix together so you get color on the outside, but they’ll make white light in the middle. And then I want to use that in the cemetery sequence. You guys never bothered to do that?” So they said, “Well, we didn’t . . . You know, we think it was . . .” So Bert said, “Well, Hopper sounds really excited. He says he’s going to win Cannes. That sounds like a hell of an idea.” And then Bert said, “I’ve got to tell you one other thing: I hired Hopper to direct this movie, and he’s going to direct this movie.”

SHAFRAZI: Schneider said that?

HOPPER: Yeah. He didn’t tell me about it until after the film was done, but I knew we were having problems. Paul and I had gone off to find locations and places where the crew could live. When we got to New Orleans it was really dangerous because there were these marines who wanted to take me apart because I had long hair. You’d hear a lot of stories at that time of guys getting cut with razors and things. It was so bad that we skipped going to Texas. We went from New Mexico over to New Orleans, and when we got there—it had been two-and-a-half weeks or something—I called New York to see how Peter and Terry were doing on the screenplay. They hadn’t started writing it! I said, “But we’re shooting in a week-and-a-half!” So I got on a plane and went to New York. I went to Henry Fonda’s house, where Peter was staying, but he wasn’t there. I found them all having dinner with Rip Torn and a bunch of people at an Italian restaurant around a big Last Supper–kind of a table. I went up and said to Peter, “What the fuck is going on, man? Do you know how rough it is out there? We had to bypass Texas because of all these guys . . .” Rip said, “Terry and I are from Texas! I don’t like what you’re saying.” Anyway, we get in a big hassle. I later got sued and had to pay Rip $1 million for saying that I cut him out of the picture because he pulled a knife on me. But I hired a secretary and wrote the fucking thing in 10 days. It wasn’t a great screenplay, but I wrote it so they had a document. Terry never did anything. He broke his hip, so he couldn’t come on the shoot. He let me use his office. But later they all sued me. I paid them more money than I made on Easy Rider.

SHAFRAZI: How did Jack Nicholson get involved in Easy Rider?

HOPPER: Well, I had this guy, Jack Starrett, who became a director. He had played football in Texas, and was a really good actor. He was the guy I wanted. So Bert Schneider called me into his office. Bert never wanted to see anything until the first cut. That’s the way he worked—after he saw the first cut, he got involved. But he calls me into his office and says, “I haven’t asked you to do anything, but I want you to use Jack Nicholson.” I said, “But Nicholson is not right for the part. Starrett is.” He said, “Right or wrong, I want you to use Jack.” I said, “Okay, Bert, but you’re fucking up my movie!” [all laugh] You know? That was it! And then, of course, Jack was brilliant. Jack was great.

SHAFRAZI: And you had a great time doing the film.

HOPPER: Oh, wonderful. We had a great time on the shoot. I didn’t know this at the time, but Jack was also sent as a watchdog to see if I was okay. [laughs] I was into making the movie, man.

BRANT: You and Jack have stayed friends ever since.

HOPPER: Yeah, absolutely. Close friends. Old friends. I don’t see him very much. I don’t see anybody very much.

SHAFRAZI: One of the other interesting things about Easy Rider is the fact that about a decade before the advent of MTV and the music video, you did something radical with the music in the movie: The music in Easy Rider is not orchestra music. It’s not a score. It’s this music by bands and artists who were contemporary for the time. The music in Easy Rider is pop music—and you were one of the first filmmakers to use music in film in that way.

HOPPER: I think Easy Rider might have been the first time that someone made a film using found music instead of an orchestral score. No one had really used found music in a movie before, except to play on radios or when someone was singing in a scene. But I wanted Easy Rider to be kind of a time capsule for that period, so while I was editing the film I would listen to the radio. That’s where I got “Born to Be Wild” and “The Pusher” and all those songs. Orson Welles told me, “Don’t get confused. Use your best shots, and if the music works, it works, if not,