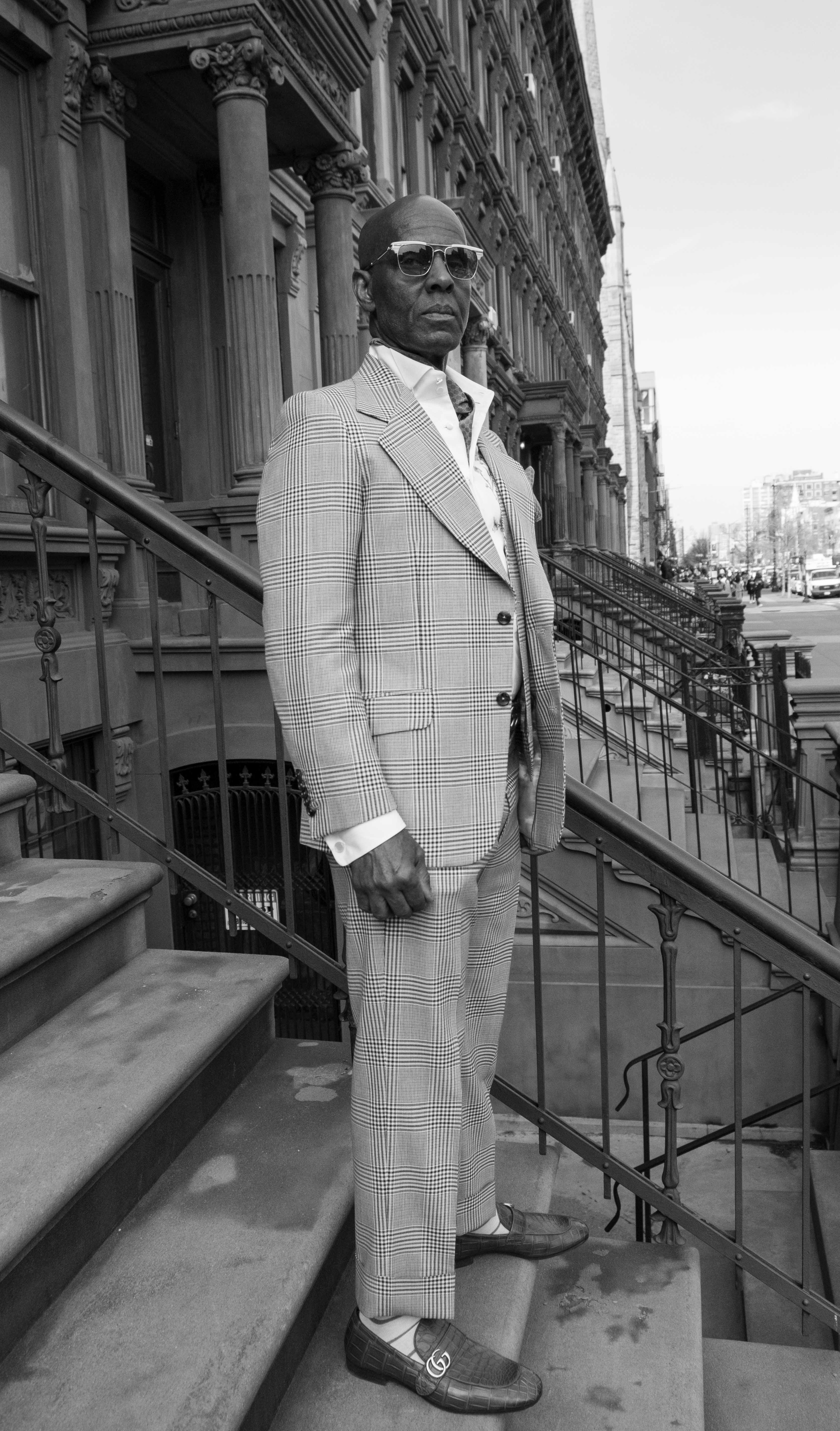

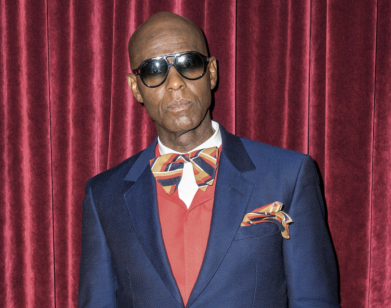

Dapper Dan on Gucci, gangsters, and his unstoppable fashion empire

Steve Jobs, quoting Pablo Picasso or maybe the literary critic Lionel Trilling, once said: “Good artists copy; great artists steal.” The line is likely apocryphal, but it could have easily come from Daniel Day, a.k.a. Dapper Dan, the Harlem couturier famous for sampling and remixing the look of luxury fashion in flamboyant and totally unexpected ways.

When Day opened his Harlem boutique in 1982, hip-hop was just beginning to flirt with the mainstream and an entire culture was being built around it. Day’s early designs—one of his trademark moves was turning en-vogue logos (Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Fendi) into patterned looks—helped define that era of rapper chic. For ten years, his jackets and tracksuits graced the backs of music royalty—Eric B. and Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, and LL Cool J were all frequent patrons. The labels from whom he was poaching, however, were less than enamored with his high-end knockoffs, and when the lawyers came calling, Day closed up shop.

Day may have gone largely under the radar, but his outsize designs live on. Thirty years later, they reappeared in Gucci’s 2018 resort show, in the form of a fur-lined, balloon-sleeve bomber jacket nearly identical to the one that Day made for Olympic track star Diane Dixon in 1989.

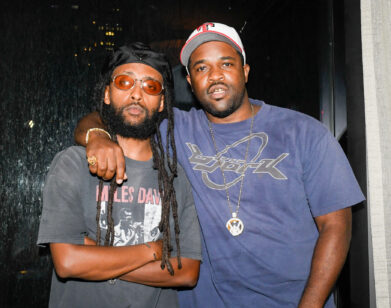

Gucci’s homage turned into an unexpected partnership: Day and the esteemed house are officially collaborating. Gucci has provided Day an atelier uptown, and Day has collaborated with the label on the design for a capsule collection to be released in July. The native New Yorker recently met up with his friend and fan, the hip-hop legend Nas, to talk about finding partners in crime, and why he’ll never leave the city that made him.

NAS: I remember hearing your name when I was growing up in Queens. We would stare at anyone in the neighborhood wearing your stuff. We’d say, “Where’d you get that from?” And they’d whisper, “Dapper Dan, Dapper Dan, Dapper Dan.” This had to be the late ’80s. I’ve been a fan of yours since I was little. What was your childhood like?

DANIEL DAY: When I grew up, there were still horses and buggies in Harlem. Can you believe that? I was on 129th Street and Lexington Avenue—a stone’s throw from the Harlem River. As a little boy, I would go down to the river bank and scoop up clay and make stuff out of it. There were shantytowns over there with hobos who taught us how to go into buildings and rip the wires out, burn them, get the copper, and put rocks in them so they’d weigh more, and then take them to the junkyard to sell.

NAS: Wow. That’s creative hustling.

DAY: I mastered gambling when I was 13. How I got popular enough to open up Dapper Dan’s was from gambling. That’s where I got my name from, and that’s where I got my education.

NAS: So you have a natural gift for dressing and getting fly. What inspired you to open the store?

DAY: As I said, I was involved in the paper game, and I made a lot of money, but I didn’t want to be associated with the street anymore. I knew I liked clothes, and I knew all the hustlers in Harlem, so I said, “I’m gonna open a clothes store and cater to all of those people.” I didn’t know that I wasn’t going to be able to buy from wholesalers and stuff. I didn’t know racism was going to keep me from expanding. I had no idea until I got involved that I couldn’t go to wholesalers and buy like other stores could. But that ended up being what changed the game. At first I taught myself everything about the fur game and started selling furs. Everybody in Harlem loved furs, but they didn’t know anything about them. They still don’t know. I see a lot of brothers walking around with dyed rabbits talking about how they got chinchilla on.

NAS: [laughs] How did the designer logos start appearing on your stuff?

DAY: I did the same thing that I did with furs—I taught myself textile printing. I came up with a chemical that I could put on leather, and it would last. I used to keep the cans secret so nobody knew what kind of ink I was using, but then my brother-in-law back-doored me and gave up the secrets. So the game leaked out, and then I had to take the game to another level. Now I can produce images on leather through computer technology.

NAS: I remember, maybe ten years ago, I wanted a Dapper Dan jacket. But nobody knew how to reach you, or maybe you didn’t want to be reached at the time. So I found somebody who made a jacket, but it was stiff, it wouldn’t move—they’d made it out of garment bags. Blessings to that guy for his Dapper Dan attempt. But with your work, you can tell it’s quality leather.

DAY: The sad thing today is that brothers don’t want to do the homework. I had to rifle through garbage bags to get wisdom, and now they just have to press a button to find out about different treatments for leathers and stuff like that. That, and their baggy pants. We tried to look like grown men, and they’re trying to look like kids.

NAS: Alpo Martinez was one of the biggest gangsters to come out of New York during my time. He had on some of the best outfits, which you designed. Was he one of your loyal customers?

DAY: Let me tell you, each age in Harlem, we have what’s called a “boy wonder”—the flyest guy of that particular era. For your era, he was that guy for sure. But Alpo got his style from this guy Jack. Alpo would wait outside the store until Jack would leave, and then he’d ask me what Jack got. So it always trickles down. You know what I mean?

NAS: Right, with the young guys watching the older guys?

DAY: It’s always been that way.

NAS: At the 2001 Grammy Awards, Nelly wore one of your designs, and that was a big deal because everyone was like, “How did he get that?” That was a good look for Nelly. Whoever my stylist was, he definitely ain’t my stylist no more because I wanted to wear that.

DAY: It was a good move for Nelly. That was one of the first outfits I made using digital prints. I would create different treatments to enhance logos, because what I learned when I opened the store was that a logo is like a diamond. A diamond signals you have money. A logo had the same effect. The more diamonds you have, the bigger you are. The more logos you have, the bigger you are.

NAS: When you saw the Gucci jacket that was nearly identical to yours, what was your reaction?

DAY: People had been copying me since 2001. We got pictures of it. It’s just because of social media that it came to everybody’s attention.

NAS: Ultimately, you and Gucci partnered together. And that made everybody—I mean everybody—happy. It’s like a celebration among the hip-hop community. Now you have an atelier.

DAY: We can’t have a shop no more. We can’t have a boutique. Now it’s an atelier. [laughs]

NAS: It’s historic. You changed the game, but you’re still in the community. You’re not afraid to speak your mind about where you came from and what these streets taught you and what you survived. That’s honorable in itself. Do you still ever design pieces like you did way back then?

DAY: That’s what I’m here for. I ain’t gonna ever stop being that; that’s who I am. Some designers, they’re like artists. They’ll paint pictures of what they see in their mind. But what I do is work with people like yourself, people who have a vision, and I try to show them how to develop their vision based on what I know. So it becomes a collaboration between myself and the customer.

NAS: You’re a New York icon. What does that mean to you?

DAY: I don’t care for labels.

NAS: Why didn’t you move to Beverly Hills?

DAY: Man, I’m never leaving Harlem!

NAS: That was a joke. That was a trick.

DAY: When I walk through the streets of Harlem—I was thinking about this the other day—when we’re looking at buildings, we’re looking at memories. Other people see architecture, I see movements.