Couture

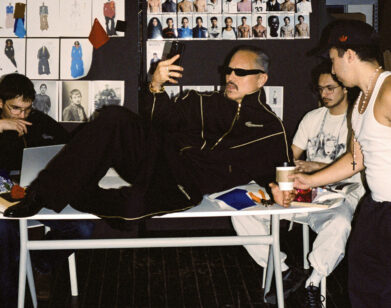

Daniel Roseberry and Christian Lacroix Discuss the State of Couture

In an era rife with monotonous Instagram trends, Schiaparelli creative director Daniel Roseberry is creating a fashion fantasy dipped in gold. At just 36 years old, he has become a dynamo of couture, delivering opulent, surrealist collections in the image of the brand’s late, great founder, Elsa. To learn more about his process and his plans, we connected the Dallas, Texas native with fellow Schiaparelli alumnus and living legend Christian Lacroix to discuss the legacy of couture in a changed world.

———

DANIEL ROSEBERRY: Hello. Bonjour.

CHRISTIAN LACROIX: Bonjour Daniel.

ROSEBERRY: I’m very, very happy and excited to meet you.

LACROIX: At last.

ROSEBERRY: Thank you so much for doing this. It’s really such an honor.

LACROIX: My pleasure.

ROSEBERRY: I never get nervous before interviews, but I’m a little nervous.

LACROIX: I’m nervous because I’m out of fashion. This weekend I had to look at what is happening now. I know couture much better than ready-to-wear, but I was quite amazed by a lot of things. My very first wish was to be a stage designer. That’s why I was totally suited to the ’80s, which was so theatrical. I admire you—to live and to play this game nowadays is not easy.

ROSEBERRY: I have some questions for you because you strike me as someone who plays the game by their own rules, which is what I’m trying to do. Fashion as an industry is a really complicated idea for me. I think social media turns the volume up so high. There’s so much nostalgia for the era you were working in, which is why I’m always referencing it.

LACROIX: I’m 70 years old, but I still feel like a young adult. I work with young people much more than people from my generation, and they’re all so fascinated and thrilled with the ’80s and ’90s. When I was a teenager in the ’60s and ’70s, I wore everything from the flea market—from the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s. Evolving that way is an oedipal thing. We all have a special feeling for whatever our mom’s generation was wearing. The ’80s and ’90s were a tacky, ugly period for me. But I was totally in the game at that time.

ROSEBERRY: I’m 36 now. I was born in 1985 in Dallas, Texas. I think I’m part of the last age of humans who remember what it was like to be a teenager before social media. Facebook started my freshman year of college. I wake up every day and yearn to get off Instagram, to shut down all of my social media and disappear. Now, I gravitate towards fashion, movies, and TV shows where the characters are not holding phones. Their problems feel much more innocent, even though it wasn’t an innocent time at all. Of course, it’s easy to fetishize it, and I do it a lot. But your work is like the crystallization of that whole period before it was all taken away by 9/11.

LACROIX: Exactly.

ROSEBERRY: That was the moment that everything died. The financial crash was the twist of the knife, but 9/11 was the end.

LACROIX: Something different started, something quite exciting, but you’re right. The way that I did fashion, I was very candid. I never learned how to sketch. I never learned how to sew. I never learned how to cut. I never learned anything.

ROSEBERRY: I’m obsessed with that because I don’t know how to sew anything. If a button falls off my shirt, I’m breaking into sweats.

LACROIX: [Laughs] Me too. Did you go to fashion school?

ROSEBERRY: I went to school, but I dropped out and focused on illustration because I love to draw, which was the key.

LACROIX: I was totally crazy about the way you did your very first show, with you sketching on the runway and all the girls becoming reality. And you were on your computer—I work on a computer. I used to be a very snobbish dandy; I never emailed. I never did anything electronic.

ROSEBERRY: Yeah, a purist. I was brushing up on a lot of things that you’ve said in the past in anticipation of this. And it’s crazy, because things you said years ago sound like you’re talking about right now. You were saying that in order for something to resonate or to have an emotional impact, it has to be a caricature of itself. Which could not be truer now with social media and everything. Looking back on your career, did you feel fulfilled when you were working? Or were you disillusioned? How did you feel when you were in your thirties and forties?

LACROIX: I was disillusioned. Really. I was never in the right place. I never had the idea I should have had. I always listened to my gut, but I felt so alone, especially in a group like LVMH. When I had lunch with [LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton chairman] Bernard Arnault, it was, “Oh, you are such a wonderful poet, but you are such a poor businessman.” He was totally thrilled with the next generation of designers, genius designers, who were interested in making money. Alexander McQueen wanted to buy stocks after their first meeting. Making money was not my thing. When Versace or Dolce and Gabbana were on yachts during the summer, I was in the south with my friends, doing normal things—drinking, dancing, going night-clubbing. But I felt reassured when I saw people crying at the end of my shows because I wanted them to cry with me.

ROSEBERRY: Right.

LACROIX: The day I came to the Schiaparelli salon was the day you presented a beautiful ready-to-wear collection. I was overwhelmed. I said, “How smart he is to translate this spirit from the couture in very simple, unexpected beige, gray, white, and brown, with just something to link it to couture, like a jewel.” I also love that you are not a prisoner of surrealism as the house was in the Schiaparelli era. Surreality exists now because we need escapism through art, especially with the war [in Ukraine] 3,000 kilometers from here. I don’t know what will happen, but I think that the more dramatic, the more difficult the world is, the more wonderful fashion will be. It’s evolving. During the First World War, they shortened everything, and wow. For the first time it was not a reference to the past.

ROSEBERRY: It’s funny what you said about making people cry, because my mantra for every season is, “I want people weeping in the front row,” and not just my mom. I think most people design clothes because they love this industry, or because they love dressing women, and that is not me at all. For me, it’s about triggering a deep, deep, emotional response from people. Couture has become the mechanism by which we can do this. And it’s true, as you said, that as the world starts to fall apart or things start heating up, I find myself running to the couture, seeking refuge inside of the process. I was just complaining about this week, because it’s fashion week, it’s ready-to-wear—you really feel the machine. I find it so much more exhausting.

LACROIX: Nobody in the press has culture anymore, only Suzy Menkes. The journalists during my time were very tough people who were able to say shit if they wanted. Today, they can’t because certain brands will cancel advertising. Now in the front row you have little girls with silly blogs without any culture.

ROSEBERRY: It’s very rare to read an actual review of a collection anymore. Most of the time, it’s just a recap—no one really tears anything apart. And I kind of like when that happens; I love reading reviews. Did you read reviews about your own work?

LACROIX: Yes, of course. Sometimes it was a negative review, but they were right. I remember once Libération was so right about ready-to- wear that I sent flowers as a thank you because they opened my eyes. It was very fair.

ROSEBERRY: I have a question for you. When I started, it was this orgasmic explosion of ideas without a lot of rigor or discipline. And since then, we’ve been working to find more structure. That’s why the last couture show was black, white, and gold. But my heart knows that it’s time to introduce color back into the collection. What was your relationship with color? Did you start from classical paintings?

LACROIX: I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Arles in the south of France, but when I was a child, colors were everywhere in the streets. I was born in ’51, and we lived next to the city on the seaside. That’s where I saw flowers with stripes and dots and colors for the first time. My mother was crazy about red. I was clad in red. She was clad in red. I’m sure you’ve seen the costumes from Arles. We had this folk tradition with silk, lace, jewels, and everything. On my mother’s side, they were very, very Catholic, almost Italian-style with rococo statues and—

ROSEBERRY: The Virgin Mary.

LACROIX: On my father’s side, they had Protestant roots. My great aunts were always in black with little white dots. They were never made up. Even Paris nowadays just has people clad in parkas and I can’t stand that. It’s changed so much.

ROSEBERRY: When I was in college, you had McQueen and Galliano defining what fashion was. In my mid-twenties, you had the modernists like Phoebe [Philo] and Raf [Simons] come in and say what’s chic is reality. The idea of doing glamour and these peacock colors, it’s coming back, but I think people’s appetite for it was lost for almost ten years because of Raf ’s first couture collection.

LACROIX: I agree.

ROSEBERRY: I always say to the team, I don’t want to treat color like Raf treated color. I don’t want to treat color like if Phoebe was doing couture. Because that’s what people are doing now. It’s almost too tasteful. It’s too safe. It’s too practically minded. The couture client is starting to have an appetite for something outrageous, but at the same time, something tender. Chic people today are nice, most of the time. That attitude, that vicious, Cruella de Vil kind of character, who honestly terrifies me, is a bit out of fashion.

LACROIX: I have to say that a certain kind of chic has vanished. There was a time when culture and money were in the same hands. Today you have poor people in culture and the wealthy in couture.

ROSEBERRY: That’s such a good point.

LACROIX: But if you keep going your own way, with what I saw with your ready-to-wear collection in the salon, chic is the name. I don’t know if the younger generation still knows that word.

ROSEBERRY: We’re trying to remember.

LACROIX: Are you in love with color?

ROSEBERRY: Well, it’s so fascinating to hear what you said about your inheritance of color from your childhood. I had a similar experience growing up, where I had a very contradictory father’s side and mother’s side. I am the product of both of them—my mom is an artist and my dad is a priest. I’m not even from Dallas, I’m from Plano. Native Americans named it “plain” because there was nothing there. A lot of what I fetishize is from scratch, a lot of it has to do with my relationship to daydreaming. I used to want to be an animator when I was young. I loved Disney movies and that very naive, childlike world.

LACROIX: I was in love with Mickey [Mouse]. Every morning I woke up and looked beside my bed to see if Mickey was there.

ROSEBERRY: You had Mickey and I had Pocahontas.

LACROIX: We’re quite similar.

ROSEBERRY: I don’t think either of us are trying to be the coolest person in the room. But I do think that making things that touch the inner child is what I’m always thinking about. I’m working with a stylist named Marie Chaix, who I absolutely adore, and she has a little boy. When he was two or three, she had him in her arms and they were walking through the salons and she noticed that he would grab certain things. That’s how I want adults to feel when they see these collections, like there’s this innocent child inside of them that’s reaching out because they like it. I don’t resonate with fashion that’s apocalyptic or negative. I know that it’s part of the culture, and it’s necessary, but I just don’t feel called to it. I think it’s funny you talk about red, because I’ve been thinking about pope red, like a cardinal red. Maybe it’s just one color mixed with black that can be something quite chic. But it’s a journey—I’m going to be starting from zero.

LACROIX: Even with shocking pink.

ROSEBERRY: I want to love shocking pink more than I do. But when I got here, everything was pink.

LACROIX: Don’t feel obliged. Perhaps Schiaparelli herself would do something astonishing nowadays if she was alive in our world—at the end she was in black. I think you are a very good choice for Schiaparelli. You’re not just a fashion designer looking for the next “It” bag. Couture needs a link to modern art. When you’re not doing fashion are you painting?

ROSEBERRY: I recently went to the Rodin Museum and I was so moved. It made me want to get back into it. I used to paint and work with my hands more. I just have to find the balance; I have to find the time.

LACROIX: The school you attended was not only a fashion school, it was an art school?

ROSEBERRY: It was a fashion school. But my mom had me in art classes since I was little. Even if they couldn’t get behind every- thing in my life, my parents could get behind my art; they were always very supportive of that. So the journey continues.

———

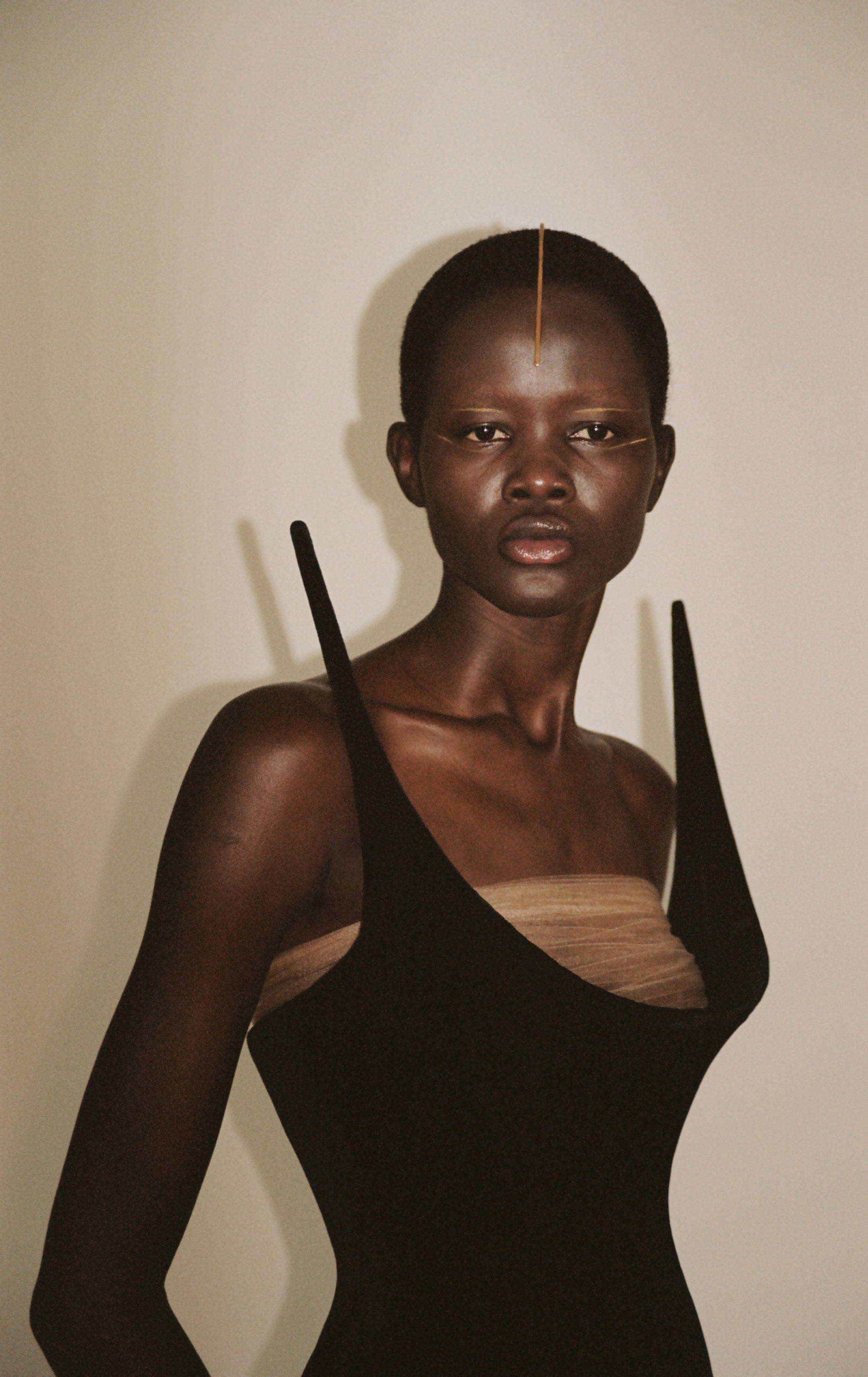

Models Shuting Yang at Elite Paris, Anyiel Majok at Select Paris, and Grace Quaye at Next Paris

Hair by Akemi Kishida using Oribe at M+A World Group

Casting by Calvin Wilson at Establishment NY

Production by Romain Ehret at Total World

Fashion Assistants Pierre Leba and Frank-Oliver Boecasse

Hair Assistant Miwa Moroki

Makeup Assistant Clara Retif